Pregnancy SmartSiteTM

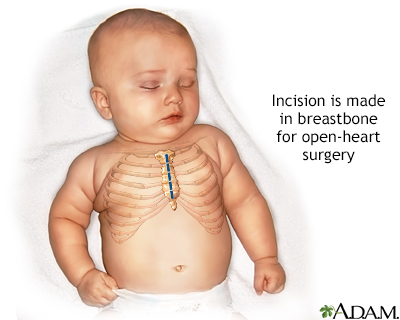

Heart surgery - pediatric; Heart surgery for children; Acquired heart disease; Heart valve surgery - children DefinitionHeart surgery in children is done to repair heart defects a child is born with (congenital heart defects) and heart diseases a child gets after birth that need surgery. The surgery is needed for the child's wellbeing. DescriptionThere are many kinds of heart defects. Some are minor, and others are more serious. Defects can occur inside the heart or in the large blood vessels outside the heart. Some heart defects may need surgery right after the baby is born. For others, your child may be able to safely wait for weeks, months or years to have surgery. One surgery may be enough to repair the heart defect, but sometimes a series of procedures is needed. Three different techniques for fixing congenital defects of the heart in children are described below. Open-heart surgery is when the surgeon uses a heart-lung bypass machine.

For some heart defect repairs, the incision is made on the side of the chest, between the ribs. This is called a thoracotomy. It is sometimes called closed-heart surgery. This surgery may be done using special instruments and a camera. In most cases, a heart-lung bypass machine is not needed with this approach. Not all heart defects are able to be treated with this approach. Another way to fix defects in the heart is to insert small tubes into an artery in the leg and pass them up to the heart. This is called a cardiac catheterization. Only some heart defects can be repaired this way. A related topic is congenital heart defect corrective surgeries. Why the Procedure Is PerformedSome heart defects need repair soon after birth. For others, it is better to wait weeks, months, or years. Certain heart defects may not need to be repaired. In general, symptoms that indicate that surgery is needed are:

RisksHospitals and medical centers that perform heart surgery on children have surgeons, nurses, and technicians who are specially trained to perform these surgeries. They also have staff that will take care of your child after surgery. Risks of any surgery are:

Additional risks of heart surgery are:

Before the ProcedureIf your child is old enough to talk, tell them about the surgery. If you have a preschool-aged child, tell them the day before what will happen. Say, for example, "We are going to the hospital to stay for a few days. The doctor is going to do an operation on your heart to make it work better." If your child is older, start talking about the procedure 1 week before the surgery. You should involve the child's life specialist (someone who helps children and their families during times like major surgery) and show the child the hospital and surgical areas. Your child may need many different tests:

Always tell your child's health care provider what medicines your child is taking, including medicines, drugs, herbs, and vitamins you bought without a prescription. During the week before surgery:

On the day of the surgery:

After the ProcedureMost children who have open-heart surgery need to stay in the intensive care unit (ICU) for 2 to 4 days right after surgery. They most often stay in the hospital for 5 to 7 more days after they leave the ICU. Stays in the intensive care unit and the hospital are often shorter for people who have closed-heart surgery. More complex heart surgery may require your child to stay in hospital for weeks or months after surgery. During their time in the ICU, your child will have:

By the time your child leaves the ICU, most of the tubes and wires will have been removed. Your child will be encouraged to start many of their regular daily activities. Some children may begin eating or drinking on their own within 1 or 2 days, but others may take longer. When your child is discharged from the hospital, parents and caregivers are taught what activities are OK for their child to do, how to care for the incision(s), and how to give medicines their child may need. Your child often needs at least several more weeks at home to recover. Talk with your provider about when your child can return to school or daycare. Your child will need follow-up visits with a cardiologist (heart doctor), often every 6 to 12 months. Your child may need to take antibiotics before going to the dentist for teeth cleaning or other dental procedures, to prevent serious heart infections. Ask the cardiologist if this is necessary. Outlook (Prognosis)The outcome of heart surgery depends on the child's condition, the type of defect, and the type of surgery that was done. Many children recover completely and lead normal, active lives. ReferencesDouglas WI, Beers K. Technical considerations in pediatric cardiac surgery. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2021;30(2):151043. PMID: 33992311 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33992311/. Ginther RM, Forbess JM. Pediatric cardiopulmonary bypass. In: Zimmerman JJ, Clark RSB, Furhman BP, eds. Fuhrman and Zimmerman's Pediatric Critical Care. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 35. Mahmood F, Robitaille M, Golhar SRY. Perioperative echocardiography and point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS). In: Gropper MA, Cohen NH, Eriksson LI, Fleisher LA, Johnson-Akeju S, Leslie K, eds. Miller's Anesthesia. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2025:chap 33. LeRoy S, Elixson EM, O'Brien P, et al. Recommendations for preparing children and adolescents for invasive cardiac procedures: a statement from the American Heart Association Pediatric Nursing Subcommittee of the Council on Cardiovascular Nursing in collaboration with the Council on Cardiovascular Diseases of the Young. Circulation. 2003;108(20):2550-2564. PMID: 14623793 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14623793/. Valente AM, Dorfman AL, Babu-Narayan SV, Krieger EV. Congenital heart disease in the adolescent and adult. In: Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Tomaselli GF, Braunwald E, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 82. | ||

| ||

Review Date: 1/17/2025 Reviewed By: Charles I. Schwartz, MD, FAAP, Clinical Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, General Pediatrician at PennCare for Kids, Phoenixville, PA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team. View References The information provided herein should not be used during any medical emergency or for the diagnosis or treatment of any medical condition. A licensed medical professional should be consulted for diagnosis and treatment of any and all medical conditions. Links to other sites are provided for information only -- they do not constitute endorsements of those other sites. No warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied, is made as to the accuracy, reliability, timeliness, or correctness of any translations made by a third-party service of the information provided herein into any other language. © 1997- A.D.A.M., a business unit of Ebix, Inc. Any duplication or distribution of the information contained herein is strictly prohibited. | ||

Infant open heart ...

Infant open heart ...