Pregnancy SmartSiteTM

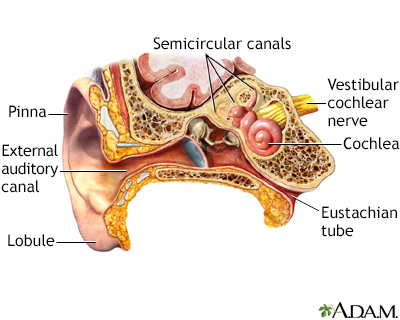

OME; Secretory otitis media; Serous otitis media; Silent otitis media; Silent ear infection; Glue ear DefinitionOtitis media with effusion (OME) is thick or sticky fluid behind the eardrum in the middle ear. It occurs without an ear infection. Note: This article is intended to be applicable to children only. There are additional considerations for teens and adults. CausesThe Eustachian tube connects the inside of the ear to the back of the throat. This tube helps drain fluid to prevent it from building up in the ear. The fluid drains from the tube and is swallowed. OME and ear infections are connected in two ways:

The following can cause swelling of the Eustachian tube lining that leads to increased fluid in the middle ear:

The following can cause the Eustachian tube to close or become blocked:

Getting water in a baby's ears will not lead to a blocked Eustachian tube. OME is most common in winter or early spring, but it can occur at any time of year. It can affect people of any age. It occurs most often in children under age 2, but is rare in newborns. Younger children get OME more often than older children or adults for several reasons:

The fluid in OME is often thin and watery. In the past, it was thought that the fluid got thicker the longer it was present in the ear. ("Glue ear" is a common name given to OME with thick fluid.) However, fluid thickness is now thought to be related to the ear itself, rather than to how long the fluid is present. SymptomsUnlike children with an ear infection, children with OME do not act sick. OME often does not have obvious symptoms. Older children and adults often complain of muffled hearing or a sense of fullness in the ear. Younger children may turn up the television volume because of hearing loss. Exams and TestsThe health care provider may find OME while checking your child's ears after an ear infection has been treated. The provider will examine the eardrum and look for certain changes, such as:

A test called tympanometry is an accurate tool for diagnosing OME. The results of this test can help tell the amount and thickness of the fluid. The fluid in the middle ear can be accurately detected with:

An audiometer or other type of formal hearing test may be done. This can help the provider decide on treatment. TreatmentMost providers will not treat OME in children at first, unless there are also signs of an infection. Instead, they will recheck the problem in 2 to 3 months. You can make the following changes to help clear up the fluid behind the eardrum:

Most often the fluid will clear on its own. Your child's provider may suggest watching the condition for a while to see if it is getting worse before recommending treatment. If the fluid is still present after 6 weeks, the provider may recommend:

In a child, if the fluid is still present at 8 to 12 weeks, antibiotics may be tried. These medicines are not always helpful. At this point, teens and adults need additional testing to check for a tumor in the nose or throat. At some point, the child's hearing should be tested. If there is significant hearing loss (more than 20 decibels), antibiotics or ear tubes might be needed. If the fluid is still present after 4 to 6 months, tubes are probably needed, even if there is no major hearing loss. Sometimes the adenoids must be taken out for the Eustachian tube to work properly. Outlook (Prognosis)OME most often goes away on its own over a few weeks or months. Treatment may speed up this process. Glue ear may not clear up as quickly as OME with a thinner fluid. OME is most often not life threatening. Most children do not have long-term damage to their hearing or speaking ability, even when the fluid remains for many months. When to Contact a Medical ProfessionalContact your provider if:

PreventionHelping your child reduce the risk of ear infections can help prevent OME. ReferencesPelton SI. Otitis externa, otitis media, and mastoiditis. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 61. Player B. Otitis media. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, et al, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 22nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2025:chap 680. Schilder AGM, Rosenfeld RM, Venekamp RP. Acute otitis media and otitis media with effusion. In: Flint PW, Francis HW, Haughey BH, et al, eds. Cummings Otolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 199. | ||

| ||

Review Date: 7/31/2024 Reviewed By: Charles I. Schwartz, MD, FAAP, Clinical Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, General Pediatrician at PennCare for Kids, Phoenixville, PA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team. View References

The information provided herein should not be used during any medical emergency or for the diagnosis or treatment of any medical condition. A licensed medical professional should be consulted for diagnosis and treatment of any and all medical conditions. Links to other sites are provided for information only -- they do not constitute endorsements of those other sites. No warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied, is made as to the accuracy, reliability, timeliness, or correctness of any translations made by a third-party service of the information provided herein into any other language. All content on this site including text, images, graphics, audio, video, data, metadata, and compilations is protected by copyright and other intellectual property laws. You may view the content for personal, noncommercial use. Any other use requires prior written consent from Ebix. You may not copy, reproduce, distribute, transmit, display, publish, reverse-engineer, adapt, modify, store beyond ordinary browser caching, index, mine, scrape, or create derivative works from this content. You may not use automated tools to access or extract content, including to create embeddings, vectors, datasets, or indexes for retrieval systems. Use of any content for training, fine-tuning, calibrating, testing, evaluating, or improving AI systems of any kind is prohibited without express written consent. This includes large language models, machine learning models, neural networks, generative systems, retrieval-augmented systems, and any software that ingests content to produce outputs. Any unauthorized use of the content including AI-related use is a violation of our rights and may result in legal action, damages, and statutory penalties to the fullest extent permitted by law. Ebix reserves the right to enforce its rights through legal, technological, and contractual measures. | ||

Ear anatomy

Ear anatomy Middle ear infecti...

Middle ear infecti...