Pregnancy SmartSiteTM

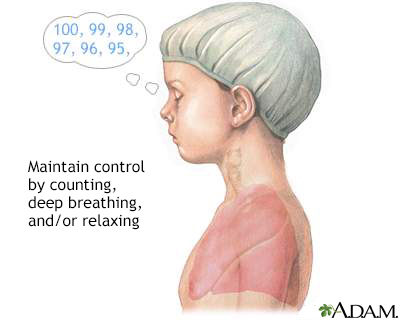

Test/procedure preparation - adolescent; Preparing adolescent for test/procedure; Preparing for a medical test or procedure - adolescent DefinitionPreparing for a medical test or procedure can reduce anxiety, encourage cooperation, and help your teen develop coping skills. InformationThere are many ways to help teens prepare for a medical test or procedure. First, explain the reasons for the procedure. Let your teen take part and make as many decisions as possible. PREPARING BEFORE THE PROCEDURE Explain the procedure in correct medical terms. Tell your teen why the test is being done. (Ask your health care provider to explain it if you are not sure.) Understanding the need for the procedure may reduce your teen's anxiety. To the best of your ability, describe how the test will feel. Allow your teen to practice the positions or movements that will be required for the test, such as the fetal position for a lumbar puncture (spinal tap). Be honest about discomfort your teen may feel, but don't dwell on it. It may help to stress the benefits of the test, and to say that the test results may provide more information. Talk about things that your teen may enjoy after the test, such as feeling better or going home. Rewards such as shopping trips or movies may be helpful if the adolescent is able to do them. Tell your teen as much as you can about the equipment that will be used for the test. If the procedure will take place in a new location, it may help to tour the facility with your teen before the test. Suggest ways for your teen to stay calm, such as:

When possible, let your teen make some decisions, such as deciding the time of day or the date of the procedure. The more control a person has over a procedure, the less painful and anxiety-producing it is likely to be. Allow your teen to participate in simple tasks during the procedure, such as holding an instrument, if allowed. Discuss possible risks. Teens are often concerned about risks, particularly about any effects on their appearance, mental function, and sexuality. Address these fears honestly and openly if at all possible. Provide information about any appearance changes or other possible side effects the test may cause. Older teens may benefit from videos that show adolescents of the same age explaining the procedure. Ask your provider if such videos are available for your teen to view. It may also be helpful for your adolescent to discuss any concerns with peers who have managed similar stressful procedures. Ask your provider if they know any teens who are interested in doing peer counseling, or if they can recommend a local support group. DURING THE PROCEDURE If the procedure is done at a hospital or your provider's office, ask if you can stay with your teen. However, if your teen doesn't want you to be there, honor this wish. Out of respect for your adolescent's growing need for privacy and independence, don't allow peers or siblings to watch the procedure unless your teen asks them to be there. Do not show your own anxiety. Looking anxious will make your adolescent more upset and worried. Research suggests that children are more cooperative if their parents take measures to reduce their own anxiety. Other considerations:

ReferencesAmerican Cancer Society website. When your child has cancer. www.cancer.org/cancer/survivorship/children-with-cancer.html. Accessed June 13, 2024. Chow CH, Van Lieshout RJ, Schmidt LA, Dobson KG, Buckley N. Systematic review: audiovisual interventions for reducing preoperative anxiety in children undergoing elective surgery. J Pediatr Psychol. 2016;41(2):182-203. PMID: 26476281 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26476281/. Kain ZN, Fortier MA, Chorney JM, Mayes L. Web-based tailored intervention for preparation of parents and children for outpatient surgery (WebTIPS): development. Anesth Analg. 2015;120(4):905-914. PMID: 25790212 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25790212/. Lerwick JL. Minimizing pediatric healthcare-induced anxiety and trauma. World J Clin Pediatr. 2016;5(2):143-150. PMID: 27170924 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27170924/. | ||

| ||

Review Date: 4/17/2024 Reviewed By: Neil K. Kaneshiro, MD, MHA, Clinical Professor of Pediatrics, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team. View References The information provided herein should not be used during any medical emergency or for the diagnosis or treatment of any medical condition. A licensed medical professional should be consulted for diagnosis and treatment of any and all medical conditions. Links to other sites are provided for information only -- they do not constitute endorsements of those other sites. No warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied, is made as to the accuracy, reliability, timeliness, or correctness of any translations made by a third-party service of the information provided herein into any other language. © 1997- A.D.A.M., a business unit of Ebix, Inc. Any duplication or distribution of the information contained herein is strictly prohibited. | ||

Adolescent control...

Adolescent control...