Pregnancy SmartSiteTM

Hydatid mole; Molar pregnancy; Hyperemesis - molar DefinitionHydatidiform mole (HM) is a rare mass or growth that forms inside the womb (uterus) at the beginning of a pregnancy. It is a type of gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD). CausesHM, or molar pregnancy, results from abnormal fertilization of the oocyte (egg). It results in an abnormal fetus. The placenta grows normally with little or no growth of the fetal tissue. The placental tissue forms a mass in the uterus. On ultrasound, this mass often has a grape-like appearance, as it contains many small cysts. The chance of mole formation is higher in older women. A history of mole in earlier years is also a risk factor. Molar pregnancy can be of two types:

There is no way to prevent formation of a molar pregnancy. SymptomsSymptoms of a molar pregnancy may include:

Exams and TestsYour health care provider will perform a pelvic exam, which may show signs similar to a normal pregnancy. However, the size of the womb may be abnormal and there may be no heart sounds from the baby. Also, there may be some vaginal bleeding. A pregnancy ultrasound will show a snowstorm appearance with an abnormal placenta, with or without some development of a baby. Tests done may include:

TreatmentIf your provider suspects a molar pregnancy, removal of the abnormal tissue with a dilation and curettage (D&C) will most likely be suggested. D&C may also be done using suction. This is called suction aspiration (The method uses a suction cup to remove contents from the uterus). Very rarely, a partial molar pregnancy can continue. A woman may choose to continue her pregnancy in the hope of having a successful birth and delivery. However, these are very high-risk pregnancies. Risks may include bleeding, problems with blood pressure, and premature delivery (having the baby before it is fully developed). In rare cases, the fetus is genetically normal. Women need to completely discuss the risks with their provider before continuing the pregnancy. A hysterectomy (surgery to remove the uterus) may be an option for older women who do not wish to become pregnant in the future. After treatment, your hCG level will be followed. It is important to avoid another pregnancy and to use a reliable contraceptive for 6 to 12 months after treatment for a molar pregnancy. This time allows for accurate testing to be sure that the abnormal tissue does not grow back. Women who get pregnant too soon after a molar pregnancy are at high risk of having another molar pregnancy. Outlook (Prognosis)Most HMs are noncancerous (benign). Treatment is usually successful. Close follow-up by your provider is important to ensure that signs of the molar pregnancy are gone and pregnancy hormone levels return to normal. About 15% of cases of HM can become invasive. These moles can grow deep into the uterine wall and cause bleeding or other complications. This type of mole most often responds well to medicines. In very few cases of complete HM, moles develop into a choriocarcinoma. This is a fast-growing cancer. It is usually successfully treated with chemotherapy, but can be life threatening. Possible ComplicationsComplications of molar pregnancy may include:

Complications from surgery to remove a molar pregnancy may include:

ReferencesNica A, Bouchard-Fortier G, Covens A. Gestational trophoblastic disease: hydatidiform mole, nonmetastatic and metastatic gestational trophoblastic tumor: diagnosis and management. In: Gershenson DM, Lentz GM, Valea FA, Lobo RA, eds. Comprehensive Gynecology. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 34. Soper JT. Gestational trophoblastic disease. In: Creasman WT, Mutch DG, Mannel RS, Tewari KS, eds. DiSaia and Creasman Clinical Gynecologic Oncology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2023:chap 7. Tidy J. Gestational trophoblastic disease. In: Magowan B, ed. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2023:chap 15. | ||

| ||

Review Date: 10/15/2024 Reviewed By: John D. Jacobson, MD, Professor Emeritus, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Loma Linda University School of Medicine, Loma Linda, CA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team. View References The information provided herein should not be used during any medical emergency or for the diagnosis or treatment of any medical condition. A licensed medical professional should be consulted for diagnosis and treatment of any and all medical conditions. Links to other sites are provided for information only -- they do not constitute endorsements of those other sites. No warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied, is made as to the accuracy, reliability, timeliness, or correctness of any translations made by a third-party service of the information provided herein into any other language. © 1997- A.D.A.M., a business unit of Ebix, Inc. Any duplication or distribution of the information contained herein is strictly prohibited. | ||

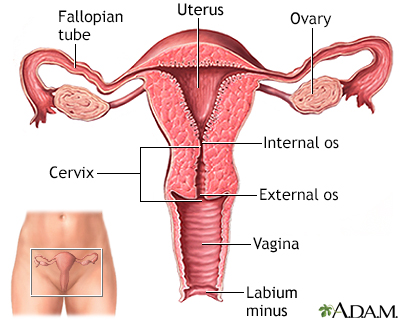

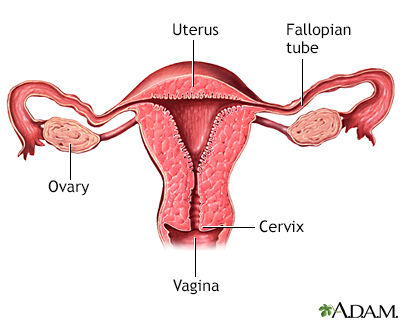

Uterus

Uterus Normal uterine ana...

Normal uterine ana...