| Step 2: What is asthma? |

Asthma is a chronic, inflammatory disorder of the airways. A person with asthma may not feel symptoms all the time. But when an "asthma episode" (also called an asthma attack) occurs, it becomes hard for air to pass through the airways. The result is breathing difficulties, wheezing, coughing, or other symptoms.

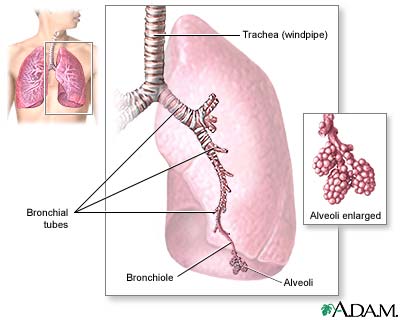

To understand asthma, it is helpful to understand how air moves in and out of the lungs:

- Fresh, oxygen-rich air enters the mouth and nose and moves through the throat, down the trachea (also called your windpipe).

- The trachea splits into two major airways called bronchial tubes.

- The bronchial tubes divide into smaller and smaller airways in the lungs.

- The air finally reaches the smallest airways, called bronchioles.

- The air enters tiny air sacs called alveoli; this is where oxygen is transferred into your bood and carbon dioxide, a waste product from the body that is picked up to be removed from the blood.

- The air is exhaled out.

|

What causes asthma symptoms?

Classic asthma symptoms, such as difficulty breathing, wheezing, chest tightness, and coughing, happen when the airways become narrow and blocked. Three things happen during an asthma episode:

- Inflammation -- The lining of the airways becomes very inflamed, which means the airways swell with fluid and cells (in response to an allergic reaction, exercise, or other trigger). Chronic inflammation is now thought to be the major cause of asthma. In fact, the purpose of steroid and some other "control" medications is to keep inflammation as low as possible and prevent attacks.

- Airway muscles tighten -- The rings of muscles that wrap the airways constrict tighter and tighter, pinching the airway closed. The drugs used to relax the muscles are called "bronchodilators."

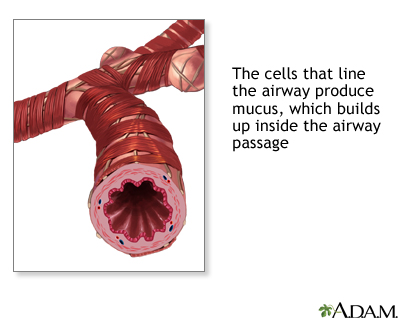

- Fluid buildup -- The cells that line the airway produce excess mucus, which collects inside the airway passage.

People with asthma have very sensitive airways that are constantly on the verge of over-reacting to asthma triggers. It doesn't take much for the airways to become inflamed, constricted, and filled with fluid.

NormalInflammationConstrictionMucus build-up

| Click the buttons above to see what a bronchiole looks like during an asthma attack. Notice that in the normal airway, there is a lot of room for air to move back and forth during the breathing process. Compare that to an airway that is inflamed, constricted, and filled with fluid, where there is almost no room for air to flow. |

What triggers asthma?

Asthma can be triggered by just about all of the same things that trigger allergies. It also can be triggered by cold air, exercise, and other factors. Possible asthma triggers include:

- Pollen, dust mites, indoor and outdoor mold, pet dander, cockroaches, and other allergens

- Exercise (running, jumping, physical activity)

- Smoke from tobacco or a fireplace; indoor and outdoor air pollution

- Viral infections (colds, flu, acute bronchitis, pneumonia)

- Gastroesophageal reflux (GERD) occurs when the contents of the stomach move back up into the esophagus, causing heartburn and other symptoms; this may be associated with night-time asthma

- Strong odors, perfumes, cleaning sprays, and chemical fumes

- Sinusitis and rhinitis (hay fever)

- Laughing or crying hard; yelling

- Changes in weather, especially with cold air and rain

- Aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- Non-selective beta-blockers, such as those in eye medication and some blood pressure medications

- Sulfite food preservatives, such as those used in processed potatoes, shrimp, dried fruit, beer, and wine

A key step in controlling asthma is to identify which of these triggers make your asthma worse, and then work to eliminate or avoid them. Sometimes it takes exposure to more than one of these factors before an asthma episode is triggered.

While you can't control some things, like cold viruses, you can avoid being around others who are sick. Take common-sense approaches and manage what you can.

References

National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Rockville, MD. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2007. NIH publications 08-4051.

|

Review Date:

7/29/2012 Reviewed By: Allen J. Blaivas, DO, Clinical Assistant Professor of Medicine UMDNJ-NJMS, Attending Physician in the Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine, Department of Veteran Affairs, VA New Jersey Health Care System, East Orange, NJ. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network. Previoulsy reviewed by David A. Kaufman, MD, Section Chief, Pulmonary, Critical Care & Sleep Medicine, Bridgeport Hospital-Yale New Haven Health System, and Assistant Clinical Professor, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network. (6/1/2010) |