Menstrual disorders - InDepth

Highlights

Menstrual disorders include:

- Dysmenorrhea refers to painful cramps during menstruation.

- Premenstrual syndrome refers to physical and psychological symptoms occurring prior to menstruation.

- Menorrhagia is heavy bleeding, including prolonged menstrual periods or excessive bleeding during a normal-length period.

- Metrorrhagia is bleeding at irregular intervals, particularly between expected menstrual periods.

- Amenorrhea is the absence of menstruation.

- Oligomenorrhea refers to infrequent menstrual periods. Hypomenorrhea refers to light periods.

Treatment options for menstrual disorders include:

- Acetaminophen (Tylenol) or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin) and naproxen (Aleve) can help provide pain relief for cramps.

- Oral contraceptives (birth control pills) can help regulate menstrual periods and reduce heavy bleeding. Newer continuous-dosing oral contraceptives reduce or eliminate menstrual periods. Progesterone injections (Depo-Provera) are another option. The LNG-IUS (Mirena), a progesterone intrauterine device (IUD), is often recommended as a first-line treatment for heavy bleeding.

- Endometrial ablation is a surgical option.

- In cases where medical therapy is not successful, hysterectomy may be considered.

Introduction

Menstrual disorders are problems that affect a woman's normal menstrual cycle. They include painful cramps during menstruation, abnormally heavy bleeding, or not having any bleeding.

Menstruation occurs during the years between puberty and menopause. Menstruation, also called "menses" or a "period," is the monthly flow of blood from the uterus through the cervix and out through the vagina.

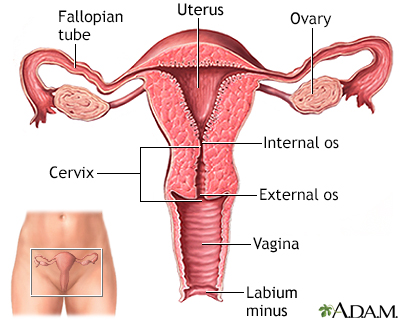

The organs and structures in the female reproductive system include:

- The uterus is a pear-shaped organ located between the bladder and lower intestine.

- The cervix is the lower portion of the uterus. It contains the cervical canal, which connects the uterine cavity with the vagina and allows menstrual blood to drain from the uterus into the vagina. The vaginal opening of the canal is called the external os. Pap smears are collected from the external os.

- The fallopian tubes connect the uterus and ovaries. Ovaries are egg-producing organs that hold 200,000 to 400,000 follicles (from folliculus, meaning "sack" in Latin). These cellular sacks contain the materials needed to produce ripened eggs, or ova. An egg develops within the follicle.

- The endometrium is the inner lining of the uterus. During pregnancy it thickens and becomes enriched with blood vessels to house and nourish the growing fetus.

- If at the end of a menstrual cycle pregnancy does not occur, the endometrium is shed and the woman starts menstruating. Menstrual flow consists of blood and mucus from the cervix and vagina.

The uterus is a hollow muscular organ located in the female pelvis between the bladder and rectum. The ovaries produce the eggs that travel through the fallopian tubes. Once the egg has left the ovary it can be fertilized and implant itself in the lining of the uterus. The main function of the uterus is to nourish the developing fetus prior to birth.

The menstrual cycle is regulated by the complex surge and fluctuations in many different reproductive hormones. These hormones work together to prepare a women's body for pregnancy. The hypothalamus (an area in the brain) and the pituitary gland control six important hormones:

- Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) is released by the hypothalamus.

- GnRH stimulates the pituitary gland to produce follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH).

- Estrogen, progesterone, and the male hormone testosterone are secreted by the ovaries at the command of FSH and LH.

The menstrual cycle begins with the first day of bleeding. The menstrual cycle is divided into three phases:

- Follicular. The follicular phase begins with menstrual bleeding. At the start of this phase, estrogen and progesterone levels are at their lowest point, which causes the uterine lining (endometrium) to break down and shed. At the same time, the hypothalamus produces GnRH which stimulates production of FSH and LH. As FSH levels increase, they signal the ovaries to produce follicles. Each follicle contains an egg. As FSH levels surge and decline, only one follicle and its egg continue to develop. The maturing follicle releases estrogen, which signals that an egg is mature and ready for release (ovulation). Throughout the follicular phase, the endometrium grows.

- Ovular. Ovulation marks the halfway point in the menstrual cycle. The ovular phase begins with a surge in LH and FSH levels. Ovulation occurs about 12 to 36 hours after LH levels surge. The follicle bursts and releases the egg, which is picked up by the fallopian tube through which it travels to the uterus. Some women experience a quick dull abdominal pain called mittelschmerz, ("middle pain" because it occurs in the middle of the monthly cycle) when the follicle ruptures. A woman is most likely to get pregnant in the 3 to 5 days before ovulation or on the day of ovulation. The egg can live for up to 24 hours after being released.

- Luteal. After releasing the egg, the ruptured follicle closes and forms the corpus luteum, a yellow mass of cells that produce estrogen and progesterone during early pregnancy. These hormones help the uterine lining to thicken and prepare for the egg's fertilization. If the egg is fertilized by a sperm cell, it implants in the uterus and pregnancy begins. If fertilization does not occur, the egg breaks apart, the corpus luteum degenerates, and estrogen and progesterone levels drop. Finally, the thickened uterine lining sloughs off and is shed along with the unfertilized egg during menstruation and the menstrual cycle begins again.

Menstrual Phases | Typical No. of Days | Hormonal Actions |

Follicular (Proliferative) Phase | Cycle Days 1 to 6: Beginning of menstruation to end of blood flow. | Estrogen and progesterone start out at their lowest levels. FSH levels rise to stimulate maturity of follicles. Ovaries start producing estrogen and levels rise, while progesterone levels remains low. |

Cycle Days 7 to 13: | The endometrium thickens to prepare for the egg implantation. | |

Ovulation | Cycle Day 14: | Surge in LH. Largest follicle bursts and releases egg into fallopian tube. |

Luteal (Secretory) Phase, also known as the Premenstrual Phase | Cycle Days 15 to 28: | Ruptured follicle develops into corpus luteum, which produces progesterone. Progesterone and estrogen stimulate blanket of blood vessels to prepare for egg implantation. |

If fertilization occurs: | Fertilized egg attaches to blanket of blood vessels that supplies nutrients for the developing placenta. Corpus luteum continues to produce estrogen and progesterone. | |

If fertilization does not occur: | Corpus luteum deteriorates. Estrogen and progesterone levels drop. The blood vessel lining sloughs off and menstruation begins. | |

Onset of Menstruation (Menarche)

The first menstruation, called the menarche, typically occurs between the ages of 12 and 13 years. Menarche generally occurs 2 to 3 years after initial breast development (breast budding). In the United States, African-American and Hispanic girls tend to mature slightly earlier than Caucasian girls. A higher body mass index (BMI) during childhood is associated with earlier puberty and menarche. Environmental factors and nutrition may also influence the age at which menstruation begins. There is a global historic trend for earlier age at menarche that manifested over the last two centuries.

Length of Monthly Cycle

The average menstrual cycle duration is about 28 days but anywhere from 21 days to 35 days is considered normal. Cycles tend to be longer during the teenage years and they also lengthen when a woman reaches her 40s. Cycle length is most irregular around the time that girls first start menstruating (menarche) and when women stop menstruating (menopause).

Duration of Periods

Most women bleed for around 3 to 5 days but a normal period can last anywhere from 2 to 7 days.

Normal Absence of Menstruation

Normal absence of periods can occur in any woman under the following circumstances:

- Menstruation stops during pregnancy. Some women continue to have irregular bleeding during the first trimester. This bleeding may indicate a miscarriage and requires immediate medical attention.

- When women breast-feed they are unlikely to ovulate. After that time, menstruation usually resumes, and they are fertile again. However, women may be fertile even if they don't menstruate and some women may be fertile while breast feeding. So it's always wise to use contraception even while breast feeding.

- Perimenopause (transition to menopause) starts when the intervals between periods begin to lengthen, and it ends with menopause itself (the complete cessation of menstruation). Menopause usually occurs at about age 51, although smokers often go through menopause earlier.

Menstrual Disorders

There are several types of menstrual disorders. Problems can range from heavy, painful periods to no periods at all. There are many variations in menstrual patterns, but in general women should be concerned when periods come fewer than 21 days or more than 3 months apart, or if they last more than 10 days. Such events may indicate ovulation problems or other medical conditions.

Dysmenorrhea is severe, frequent cramping during menstruation. Pain occurs in the lower abdomen but can spread to the lower back and thighs. Dysmenorrhea is usually referred to as primary or secondary:

- Primary dysmenorrhea. Cramping pain caused by menstruation. The cramps occur from contractions in the uterus and are usually more severe during heavy bleeding.

- Secondary dysmenorrhea. Menstrual-related pain that accompanies another medical or physical condition, such as endometriosis or uterine fibroids.

Menorrhagia is the medical term for significantly heavier periods. Menorrhagia can be caused by a number of factors.

During a normal menstrual cycle, the average woman loses about 1 ounce (30 mL) of blood and changes her sanitary products around 3 to 5 times per day.

With menorrhagia, menstrual flow lasts longer and is heavier than normal. The bleeding occurs at regular intervals (during periods), but may last more than 7 days, and menstrual flow soaks more than 5 sanitary products per day or requires product change during the night. Clot formation is common. Menorrhagia is often accompanied by dysmenorrhea because passing large clots can cause painful cramping.

Menorrhagia is a type of abnormal uterine bleeding. Other types of abnormal bleeding are:

- Metrorrhagia. Also called breakthrough bleeding, refers to bleeding that occurs at irregular intervals and with variable amounts. The bleeding occurs between periods or is unrelated to periods. Spotting or light bleeding between periods is common in girls just starting menstruation and sometimes during ovulation in young adult women.

- Menometrorrhagia. Refers to heavy and prolonged bleeding that occurs at irregular intervals. Menometrorrhagia combines features of menorrhagia and metrorrhagia. The bleeding can occur at the time of menstruation (like menorrhagia) or in between periods (like metrorrhagia).

- Dysfunctional uterine bleeding (DUB). A general term for abnormal uterine bleeding that usually refers to extra or excessive bleeding caused by hormonal problems, usually lack of ovulation (anovulation). DUB tends to occurs either when girls begin to menstruate or when women approach menopause, but it can occur at any time during a woman's reproductive life. This term is not often used by most gynecologists.

- Other types of abnormal uterine bleeding. Include bleeding after sex and bleeding after menopause. Postmenopausal bleeding is not normal and can be a sign of a serious condition.

Amenorrhea is the absence of menstruation. There are two categories: primary amenorrhea and secondary amenorrhea. These terms refer to the time when menstruation stops:

- Primary amenorrhea. Occurs when a girl does not begin to menstruate by age 16. Girls who show no signs of sexual development (breast development and pubic hair) by age 13 should be evaluated by a doctor. Any girl who does not have her period by age 15 should be evaluated for primary amenorrhea.

- Secondary amenorrhea. Occurs when periods that were previously regular stop for at least 3 months.

Oligomenorrhea is a condition in which menstrual cycles are infrequent, occurring more than 35 days apart. It is very common in early adolescence and does not usually indicate a medical problem. Light or scanty flow is also common in the first years after menarche and before menopause.

When girls first menstruate they often do not have regular cycles for several years. Even healthy cycles in adult women can vary by a few days from month to month. Periods may occur every 3 weeks in some women, and every 5 weeks in others. Flow also varies and can be heavy or light. Skipping a period and then having a heavy flow may occur; this is most likely due to missed ovulation rather than a miscarriage.

Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) is a set of physical, emotional, and behavioral symptoms that occur during the last week of the luteal phase (a week before menstruation) in most cycles. The symptoms typically do not start until at least day 13 in the cycle, and resolve within 4 days after bleeding begins.

Women may begin to have premenstrual syndrome symptoms at any time during their reproductive years, but it usually occurs when they are in their late 20s to early 40s. Once established, the symptoms tend to remain fairly constant until menopause, although they can vary from cycle to cycle.

Causes

Many different factors can trigger menstrual disorders, including hormone imbalances, genetic factors, clotting disorders, and pelvic diseases.

Primary dysmenorrhea is caused by prostaglandins, hormone-like substances that are produced in the uterus and cause the uterine muscle to contract. Prostaglandins also play a role in the heavy bleeding that causes dysmenorrhea.

Secondary dysmenorrhea can be caused by a number of medical conditions. Common causes of secondary dysmenorrhea include:

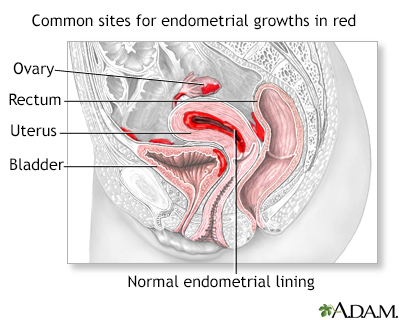

- Endometriosis.Endometriosis is a chronic and often progressive disease that develops when the tissue that lines the uterus (endometrium) grows onto other areas, such as the ovaries, peritoneum, bowels, or bladder. It often causes chronic pelvic pain.

- Uterine Fibroids.Fibroids are noncancerous growths on the walls of the uterus. They can cause heavy bleeding during menstruation and cramping pain.

- Other Causes. Pelvic inflammatory disease, ovarian cysts, and ectopic pregnancy. The intrauterine device (IUD) contraceptive can also cause secondary dysmenorrhea.

There are many possible causes for heavy bleeding:

- Hormonal Imbalances. Imbalances in estrogen and progesterone levels can cause heavy bleeding. Hormonal imbalances are common around the time of menarche and menopause.

- Ovulation Problems. If ovulation does not occur (anovulation), the body stops producing progesterone, which can cause heavy bleeding.

- Uterine Fibroids. Uterine fibroids are a very common cause of heavy and prolonged bleeding.

- Uterine Polyps. Uterine polyps (small benign growths) and other structural problems or other abnormalities in the uterine cavity may cause bleeding.

- Endometriosis and Adenomyosis. Endometriosis, a condition in which the cells that line the uterus grow outside of the uterus in other areas, such as the ovaries, can cause heavy bleeding. Adenomyosis, a related condition where endometrial tissue develops within the muscle layers of the uterus, can also cause heavy bleeding and menstrual pain.

- Medications and Contraceptives. Certain drugs, including anticoagulants and anti-inflammatory medications, can cause heavy bleeding. Problems linked to some birth control methods, such as birth control pills or intrauterine devices (IUDs) can cause bleeding.

- Bleeding Disorders. Bleeding disorders that reduce blood clotting can cause heavy menstrual bleeding. Most of these disorders have a genetic basis. Von Willebrand disease is the most common of these bleeding disorders.

- Cancer. Rarely, uterine, ovarian, and cervical cancer can cause excessive bleeding.

- Infection. Infection of the uterus or cervix can cause bleeding.

- Pregnancy or Miscarriage. Spotting is very common during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy. Heavier bleeding may also occur. Heavy bleeding during the first trimester may be a sign of miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy, but it may also be due to less serious causes that do not harm the woman or her baby.

- Other Medical Conditions. Systemic lupus erythematosus, diabetes, pelvic inflammatory disorder, cirrhosis, and thyroid disorders can cause heavy bleeding.

Fibroid tumors may not need to be removed if they are not causing pain, bleeding excessively, or growing rapidly.

Normal causes of skipped or irregular periods include pregnancy, breastfeeding, hormonal contraception, and perimenopause. Skipped periods are also common during adolescence, when it may take a while before ovulation occurs regularly. Consistently absent periods may be due to the following factors:

- Delayed Puberty. A common cause of primary amenorrhea (absence of periods) is delayed puberty due to genetic factors. Failure of ovarian development is the most common cause of primary amenorrhea.

- Hormonal Changes and Puberty. Oligomenorrhea (infrequent menstruation) is commonly experienced by girls who are just beginning to have their periods.

- Weight Loss and Eating Disorders. Eating disorders are a common cause of amenorrhea in adolescent girls. Extreme weight loss and reduced fat stores lead to hormonal changes that include low thyroid levels (hypothyroidism) and elevated stress hormone levels (hypercortisolism). These changes produce a reduction in reproductive hormones.

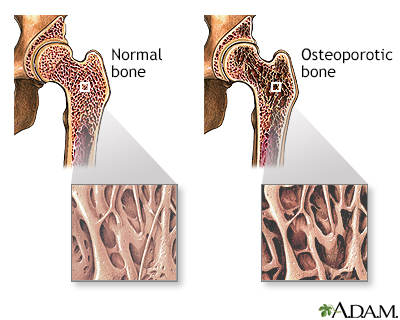

- Athletic Training. Amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea associated with vigorous physical activity may be related to stress and weight loss. A syndrome known as the female athlete triad is associated with hormonal changes that occur with the combination of eating disorders, amenorrhea, and osteopenia (loss of bone density that can lead to osteoporosis) in young women who excessively exercise.

- Stress. Physical and emotional stress may block the release of luteinizing hormone, causing temporary amenorrhea.

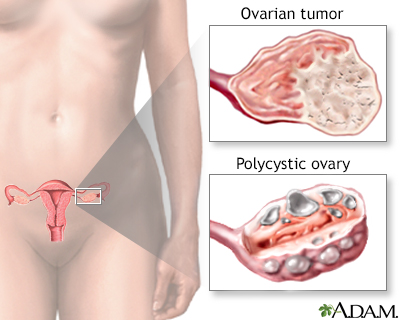

- Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS). PCOS is a condition in which the ovaries produce high amounts of androgens (male hormones), particularly testosterone. Amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea is quite common in women who have PCOS.

- Elevated Prolactin Levels (Hyperprolactinemia). Prolactin is a hormone produced in the pituitary gland that stimulates breast development and milk production in association with pregnancy. High levels of prolactin (hyperprolactinemia) in women who are not pregnant or nursing can reduce gonadotropin hormones and inhibit ovulation, thus causing amenorrhea.

- Premature Ovarian Failure (POF). POF is the early depletion of follicles before age 40. In most cases, it leads to premature menopause. POF is a significant cause of infertility.

- Structural Problems. In some cases, structural problems or scarring in the uterus may prevent menstrual flow. Inborn genital tract abnormalities may also cause primary amenorrhea.

- Other Medical Conditions. Epilepsy, thyroid problems, celiac sprue, metabolic syndrome, and Cushing's disease are associated with amenorrhea.

If the ovaries produce too much androgen (hormones such as testosterone) a woman may develop male characteristics. This ovarian imbalance can be caused by tumors in the ovaries or adrenal glands, or polycystic ovarian disease. Virilization may include growth of excess body and facial hair, amenorrhea (loss of menstrual period) and changes in body contour.

Risk Factors

Age plays a key role in menstrual disorders. Girls who start menstruating at age 11 or younger are at higher risk for severe pain, longer periods, and longer menstrual cycles.

Women who are approaching menopause (perimenopause) may also skip periods. Occasional episodes of heavy bleeding are also common as women approach menopause.

Other risk factors include:

- Weight. Being either excessively overweight or underweight can increase the risk for dysmenorrhea (painful periods) and amenorrhea (absent periods).

- Menstrual Cycles and Flow. Longer and heavier menstrual cycles are associated with painful cramps.

- Pregnancy History. Women who have had a higher number of pregnancies are at increased risk for menorrhagia. Women who have never given birth have a higher risk of dysmenorrhea, while women who first gave birth at a young age are at lower risk.

- Smoking. Smoking can increase the risk for heavier periods.

- Stress. Physical and emotional stress may block the release of luteinizing hormone, causing temporary amenorrhea.

- Exercise. Intensive athletic training is linked with late menarche and amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea.

Complications

Menorrhagia (heavy menstrual bleeding) is the most common cause of anemia (reduction in red blood cells) in premenopausal women. A blood loss of more than 80 mL per menstrual cycle can eventually lead to anemia. Most cases of anemia are mild. Nevertheless, even mild-to-moderate anemia can reduce oxygen transport in the blood, causing symptoms such as fatigue, lightheadedness, and pale skin. Severe anemia that is not treated can lead to heart problems.

Amenorrhea (absent or irregular menstrual periods) caused by reduced estrogen levels is linked to osteopenia (loss of bone density) and osteoporosis (more severe bone loss that increases fracture risk). Because bone growth is at its peak in adolescence and young adulthood, losing bone density at that time is very dangerous and early diagnosis and treatment is essential for long-term health.

Osteoporosis is a condition characterized by progressive loss of bone density, thinning of bone tissue, and increased vulnerability to fractures. Osteoporosis may result from disease, dietary or hormonal deficiency, or advanced age. Regular weight-bearing exercise and strength training, and calcium and vitamin D supplements, can reduce and even reverse loss of bone density.

Some conditions associated with heavy bleeding, such as ovulation abnormalities, fibroids, or endometriosis, can contribute to infertility. Many conditions that cause amenorrhea, such as ovulation abnormalities and PCOS, can also cause infertility. Irregular periods from any cause may make it more difficult to conceive. Sometimes treating the underlying condition can restore fertility. In other cases, specific fertility treatments that use assisted reproductive technologies may be needed.

Menstrual disorders, particularly pain and heavy bleeding, can affect school and work productivity and social activities.

Diagnosis

Your medical history can help a health care provider determine whether a menstrual problem is caused by another medical condition. For example, non-menstrual conditions that may cause abdominal pain include appendicitis, urinary tract infections, ectopic pregnancy, and irritable bowel syndrome. Endometriosis and uterine fibroids may cause heavy bleeding and chronic pain.

Your provider may ask questions concerning:

- Menstrual cycle patterns, including length of time between periods, number of days that periods last, number of days of heavy or light bleeding.

- The presence or history of any medical conditions that might be causing menstrual problems.

- Any family history of menstrual problems.

- History of pelvic pain.

- Regular use of any medications (including vitamins and over-the-counter drugs.)

- Diet history, including caffeine and alcohol intake.

- Past or present contraceptive use.

- Any recent stressful events.

- Sexual history.

Menstrual Diary

A menstrual diary is a helpful way to keep track of changes in menstrual cycles. You should record when your period starts, how long it lasts, and the amount of bleeding and pain that occurs during the course of menstruation.

Pelvic Examination

A pelvic exam is a standard part of diagnosis. A Pap test may be done during this exam.

Blood tests can help rule out other conditions that cause menstrual disorders. For example, your provider may test thyroid function to make sure that low thyroid (hypothyroidism) is not present. Blood tests can also check follicle-stimulating hormone, estrogen, and prolactin levels.

Women who have menorrhagia (heavy bleeding) may get tests for bleeding disorders. If women are losing a lot of blood, they should also get tested for anemia.

Imaging techniques are often used to detect certain conditions that may be causing menstrual disorders. Imaging can help diagnose fibroids, endometriosis, or structural abnormalities of the reproductive organs.

Ultrasound is a painless procedure and is the standard imaging technique for evaluating the uterus and ovaries. It can help detect fibroids, uterine polyps, ovarian cysts and tumors, and obstructions in the urinary tract. Ultrasound uses sound waves to produce an image of the organs.

Transvaginal sonohysterography uses ultrasound along with a probe (transducer) placed in the vagina. Sometimes saline (salt water) is injected into the uterus to enhance visualization.

Endometrial Biopsy

When heavy or abnormal bleeding occurs, an endometrial (uterine) biopsy may be performed in a medical office. This procedure can help identify abnormal cells, which suggest that pre-cancer or cancer may be present. It may also help the doctor decide on the best hormonal treatment to use. The procedure is done without anesthesia, or local anesthetic is injected.

- The woman lies on her back with her feet in stirrups. An instrument (speculum) is inserted into the vagina to hold it open and allow the cervix to be viewed.

- The cervix is cleaned with an antiseptic liquid and then grasped with an instrument (tenaculum) that holds the uterus steady. A device called a cervical dilator may be needed to stretch the cervical canal if there is tightness (stenosis). A small, hollow plastic tube is then gently passed into the uterine cavity.

- Gentle suction removes a sample of the lining. The tissue sample and instruments are removed. A specialist called a pathologist examines the sample under a microscope.

Hysteroscopy

Hysteroscopy is a procedure that can detect the presence of fibroids, polyps, or other causes of bleeding. It may miss cases of uterine cancer, however, and is not a substitute for more invasive procedures, such as dilation and curettage (D&C) or endometrial biopsy, if cancer is suspected.

Hysteroscopy may be done either in an office or operating room setting and requires no incisions. The procedure uses a slender flexible or rigid tube called a hysteroscope, which is inserted into the vagina and through the cervix to reach the uterus. A fiber-optic light source and a tiny camera in the tube allow the health care provider to view the cavity. The uterus is filled with saline or carbon dioxide to inflate the cavity and provide better viewing. This can cause cramping.

Hysteroscopy is non-invasive, but many women find the procedure painful. The use of an anesthetic spray, such as lidocaine or an oral agent, such as a NSAID can help prevent pain from this procedure. Other complications include excessive fluid absorption, infection, and uterine perforation. Hysteroscopy is also often performed as part of other surgical procedures, such as a dilation and curettage (C&D).

Dilation and Curettage (D&C)

D&C is a more invasive procedure:

- A D&C is usually done in an outpatient setting so that the woman can return home the same day, but it sometimes requires a general anesthetic. It may need to be performed in the operating room to rule out serious conditions or treat some minor ones that may be causing the bleeding. A hysteroscopy is often performed at the same time of a D&C if endometrial mass or polyps are suspected.

- The cervix (the neck of the uterus) is dilated (opened).

- The surgeon scrapes the inside lining of the uterus and cervix.

The procedure is used to take samples of the tissue, and to relieve heavy bleeding in some instances.

Laparoscopy

Diagnostic laparoscopy, an invasive surgical procedure, is used to diagnose and treat endometriosis, a common cause of dysmenorrhea. Laparoscopy normally requires a general anesthetic, although the patient can go home the same day. The procedure involves inflating the abdomen with gas through a small abdominal incision. A fiber optic tube equipped with small camera lenses (the laparoscope) is then inserted. The health care provider uses the laparoscope to view the uterus, ovaries, tubes, and peritoneum (lining of the pelvis).

Lifestyle Changes

Dietary adjustments, starting about 14 days before a period may help some women with certain mild menstrual disorders, such as cramping. The general guidelines for a healthy diet apply to everyone; they include properly hydrating, eating plenty of whole grains, fresh fruits and vegetables, and avoiding saturated fats and commercial junk foods.

Limiting salt (sodium) may help reduce bloating. Limiting caffeine, sugar, and alcohol intake may also be beneficial.

Dietary Forms of Iron

Women who have heavy menstrual bleeding can sometimes become anemic. Eating iron-rich foods can help prevent anemia. Iron found in foods is either in the form of heme or non-heme iron. Heme iron is better absorbed than non-heme iron.

- Foods containing heme iron are the best sources for increasing or maintaining healthy iron levels. Such foods include clams, oysters, organ meats, beef, pork, poultry, and fish.

- Non-heme iron is less well absorbed. A substantial amount of the iron in meat is non-heme (although meat itself helps absorb non-heme iron). Eggs, dairy products, and iron-containing vegetables have only the non-heme form. Such vegetable products include dried beans and peas, iron-fortified cereals, bread, and pasta products, dark green leafy vegetables (chard, spinach, mustard greens, and kale), dried fruits, nuts, and seeds.

Increasing intake of vitamin C rich foods can enhance absorption of non-heme iron.

Iron Supplements

There are two forms of supplemental iron: ferrous and ferric. Ferrous iron is better absorbed and is the preferred form of iron tablets. Ferrous iron is available in three forms: ferrous fumarate, ferrous sulfate, and ferrous gluconate. Depending on the severity of your anemia, as well as your age and weight, your doctor will recommend a dosage of 60mg to 200 mg of elemental iron per day. This means taking 1 iron pill 2 to 3 times each day.

Exercise

Exercise may help reduce menstrual pain.

Applying Heat

Applying a heating pad to the abdominal area, or soaking in a hot bath, can help relieve the pain of menstrual cramps.

Menstrual Hygiene

Change tampons every 4 to 6 hours. Avoid scented pads and tampons; feminine deodorants can irritate the genital area. Douching is not recommended because it can destroy the natural bacteria normally present in the vagina. Bathing regularly is sufficient.

Medications

There are a number of different medicines prescribed for menstrual disorders.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

NSAIDs block prostaglandins, the substances that increase uterine contractions. They are effective painkillers that also help control the inflammatory factors that may be responsible for heavy menstrual bleeding.

Among the most effective NSAIDs for menstrual disorders are ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin, Midol PMS) and naproxen (Aleve), which are both available over-the-counter, and mefenamic acid (Ponstel), which requires a doctor's prescription. Long-term daily use of any NSAID can increase the risk for gastrointestinal bleeding and ulcers, so it is best to just use these drugs for a few days during the menstrual cycle.

Acetaminophen (Tylenol) is a good alternative to NSAIDs, especially for women with stomach problems or ulcers. Some products (Pamprin, Premsyn) combine acetaminophen with other drugs, such as a diuretic, to reduce bloating.

Oral contraceptives (OCs), commonly called birth control pills or "the Pill," contain combinations of an estrogen and a progesterone (in a synthetic form called progestin).

The estrogen compound used in most combination OCs is estradiol. There are many different progestins, but common types include levonorgestrel, drospirenone, and norgestrel. A four-phasic OC that contains estradiol and the progesterone dienogest, has been shown in small trials as effective for treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding.

OCs are often used to regulate periods in women with menstrual disorders, including menorrhagia (heavy bleeding), dysmenorrhea (severe pain), and amenorrhea (absence of periods). They also protect against ovarian and endometrial cancers.

Standard OCs usually comes in a 28-pill pack with 21 days of "active" (hormone) pills and 7 days of "inactive" (placebo) pills. Extended-cycle (also called "continuous-use" or "continuous-dosing") oral contraceptives aim to reduce or eliminate monthly menstrual periods. These OCs contain a combination of estradiol and the progestin levonorgestrel, but they use extending dosing of active pills with 81 to 84 days of active pills followed by 7 days of inactive or low-dose pills. Some types of continuous-dosing OCs use only active pills, which are taken 365 days a year.

Side effects

Common side effects of combination OCs include headache, nausea, bloating, breast tenderness, and bleeding between periods. The estrogen component in combination OCs is usually responsible for these side effects. In general, today's OCs are much safer than OCs of the past because they contain much lower dosages of estrogen.

However, all OCs may increase the risk for migraine, stroke, heart attack, and blood clots. The risk is highest for women who smoke, who are over age 35, or who have a history of heart disease risk factors (such as high blood pressure or diabetes) or past cardiac events. Women who have certain metabolic disorders, such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), are also at higher risk for the heart-related complications associated with these pills. Some types of combination OCs contain progestins, such as drospirenone, which have a higher risk for causing blood clots than levonorgestrel.

Progestins (synthetic progesterone) are used by women with irregular or skipped periods to restore regular cycles. They also reduce heavy bleeding and menstrual pain, and may protect against uterine and ovarian cancers. Progestin-only contraceptives may be a good option for women who are not candidates for estrogen-containing OCs, such as smokers over the age of 35.

Progestins can be delivered in various forms.

Oral

Short-term treatment of anovulatory bleeding (bleeding caused by lack of ovulation) may involve a 10- to 21-day course of an oral progestin on days 16 to 25 or 5 to 26. Medroxyprogesterone (Provera) is commonly used.

Intrauterine Device (Mirena)

An intrauterine device (IUD) that releases progestin can be very beneficial for menstrual disorders. In the United States, a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system, also called an LNG-IUS, is sold under the brand name Mirena. It is the only IUD approved by the FDA to treat heavy menstrual bleeding.

The LNG-IUS remains in place in the uterus and releases the progestin levonorgestrel for up to 5 years, therefore being considered as a good long-term options.

After the LNG-IUS is inserted, there may be heaver periods initially. However, periods become short eventually with little to no blood flow. For many women, the LNG-IUS completely stops menstrual periods.

Common side effects may include cramping, acne, back pain, breast tenderness, headache, mood changes, and nausea. The LNG-IUS may increase the risk for ovarian cysts, but such cysts usually cause no symptoms and resolve on their own. Women who have a history of pelvic inflammatory disease or who have had a serious pelvic infection should not use the LNG-IUS.

Injection (Depo-Provera)

Depo-Provera (also called Depo or DMPA) uses the progestin medroxyprogesterone acetate, which is administered by injection once every 3 months. Most women who use Depo-Provera stop menstruating altogether after a year. Depo-Provera may be beneficial for women with heavy bleeding, or pain due to endometriosis. Women who eventually want to have children should be aware that Depo-Provera can cause persistent infertility for up to 22 months after the last injection, although the average is 10 months.

Weight gain can be a problem, particularly in women who are already overweight. Women should not use Depo-Provera if they have a history of liver disease, blood clots, stroke, or cancer of the reproductive organs. Depo-Provera should not be used for longer than 2 years because it can cause loss of bone density.

Gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists are sometimes used to treat severe menorrhagia. GnRH agonists block the release of the reproductive hormones LH (luteinizing hormone) and FSH (follicular-stimulating hormone). As a result, the ovaries stop ovulating and no longer produce estrogen.

GnRH agonists include the implant goserelin (Zoladex), a monthly injection of leuprolide (Lupron Depot), and the nasal spray nafarelin (Synarel). Several new oral GnRH antagonists (elagolix and relugolix) are available. They have similar action of the ovaries as the GnRH agonists. Such drugs may be used alone or in preparation for procedures used to destroy the uterine lining. They are not generally suitable for long-term use.

Commonly reported side effects, which can be severe in some women, include menopausal-like symptoms. These symptoms include hot flashes, night sweats, changes in the vagina, weight change, and depression. The side effects vary in intensity depending on the GnRH agonist. They may be more intense with leuprolide and persist after the drug has been stopped.

The most important concern is possible osteoporosis from estrogen loss. Women should not take these drugs for more than 6 months. Add-back therapy, which provides doses of estrogen and progestin that are high enough to maintain bone density but are too low to offset the beneficial effects of the GnRH agonist, may be used.

GnRH treatments may increase the risk for birth defects. Women who are taking GnRH agonists should use non-hormonal birth control methods, such as the diaphragm, cervical cap, or condoms.

Danazol (Danocrine) is a synthetic substance that resembles a male hormone. It suppresses estrogen, and therefore menstruation, and is occasionally used (sometimes in combination with an oral contraceptive) to help prevent heavy bleeding. It is not suitable for long-term use, and due to its masculinizing side effects it is only used in rare cases. GnRH agonists have largely replaced the use of danazol.

Adverse side effects include facial hair, deepening of the voice, weight gain, acne, and reduced breast size. Danazol may also increase the risk for unhealthy cholesterol levels and it may cause birth defects.

Tranexamic acid (Lysteda) is a newer medication for treating heavy menstrual bleeding and the first non-hormonal drug for menorrhagia treatment. Tranexamic acid is given as a pill. It is an anti-fibrinolytic drug that helps blood to clot. The FDA warns that use of this medication by women who take hormonal contraceptives may increase the risk of blood clots, stroke, or heart attacks. This drug should not be taken by women who have a history of venous thromboembolism.

Surgery

Women with heavy menstrual bleeding, painful cramps, or both have surgical options available to them. Most procedures eliminate or significantly affect the possibility for childbearing, however. Hysterectomy removes the entire uterus while endometrial ablation destroys the uterine lining.

Women should be sure to ask their doctors about all medical options before undergoing surgical procedures.

In endometrial ablation, the entire lining of the uterus (the endometrium) is removed or destroyed. For most women, this procedure stops the monthly menstrual flow. In some women, menstrual flow is not stopped but is significantly reduced.

Endometrial ablation is not appropriate for women who:

- Have gone through menopause.

- Have recently been pregnant.

- Would like to have children in the future.

- Have certain gynecologic conditions such as cancer of the uterus, endometrial hyperplasia, uterine infection, or an endometrium that is too thin.

Considerations

Endometrial ablation significantly decreases the likelihood a woman will become pregnant. However, pregnancy can still occur and this procedure increases the risks of complications, including miscarriage. Women who have this procedure must be committed to not becoming pregnant and to using birth control. Sterilization after ablation is another option.

A main concern of endometrial ablation is that it may delay or make it more difficult to diagnose uterine cancer in the future. (Postmenopausal bleeding or irregular vaginal bleeding can be warning signs of uterine cancer.) Women who have endometrial ablation still have a uterus and cervix, and should continue to have regular Pap smears and pelvic exams.

Types of Endometrial Ablation

Endometrial ablation used to be performed in an operating room using electrosurgery with a resectoscope (a hysteroscope with a heated wire loop or roller ball.) Laser ablation was another older procedure. These types of endometrial ablation have largely been replaced by newer types of procedure that do not use a resectoscope.

The newer procedures can be performed either in an operating room or a doctor's office. They include:

- Radiofrequency. The NovaSure system uses a mesh electrode probe that emits electromagnetic energy to destroy the lining.

- Heated fluid. In the HydroThermAblator system, a saline solution is inserted into the uterus with a hysteroscope and heated until the lining is destroyed. In the thermal balloon method, a balloon inserted into the uterus with hysteroscope is filled with heated fluid and expanded until it touches and destroys the endometrium.

- Freezing. Cryoablation uses liquid nitrogen to freeze the uterine lining.

- Microwave. Microwave endometrial ablation applies very low-power microwaves to the uterus.

Before the Procedure

In preparing for the ablation procedure, the doctor will perform an endometrial biopsy to make sure that cancer is not present. If the woman has an intrauterine device (IUD), it must be removed before the procedure. In some cases, hormonal drugs, such as GnRH analogs, may be given a few weeks before ablation to help thin the endometrial lining.

During the Procedure

Endometrial ablation is an outpatient procedure. The doctor usually applies a local anesthetic around the cervix. (The woman also receives medication for pain and to help her relax.) The doctor will dilate the cervix before starting the procedure. Women may feel some mild cramping or discomfort, but many of the newer types of endometrial procedures can be performed in less than 10 minutes.

After the Procedure

Women may experience menstrual-like cramping for several days and frequent urination during the first 24 hours. The main side effect is watery or bloody discharge that can last for several weeks. This discharge is especially heavy in the first few days following ablation. Women need to wear pads, not tampons during this time, and to wait to have sex until the discharge has stopped. They are generally able to return to work or normal activities within a few days after the procedure.

Complications

Complications of endometrial ablation may include perforation of the uterus, injury to the intestine, hemorrhage, or infection. If heated fluid is used in the procedure, it may leak and cause burns. However, in general, the risk of complications is very low.

Nearly all women have reduced menstrual flow after endometrial ablation, and nearly half of women have their periods stop. Some women, however, may continue to have bleeding problems and ultimately decide to have second ablation procedure or a hysterectomy.

Hysterectomy is the surgical removal of the uterus.

Heavy bleeding, often from fibroids, and pelvic pain are the reasons for many hysterectomies. However, with newer medical and surgical treatments available, hysterectomies are performed less often than in the past.

In its support, hysterectomy, unlike drug treatments and less invasive procedures, cures menorrhagia completely, and most women are satisfied with the procedure. Less invasive ways of performing hysterectomy procedures such as vaginal approach, laparoscopic approach with or without robotic assistance, are also improving recovery rates and increasing satisfaction afterward. Still, any woman who is uncertain about a recommendation for a hysterectomy to treat fibroids or heavy bleeding should certainly seek a second opinion.

Some women who have hysterectomies have their ovaries removed along with their uterus. Surgical removal of the ovaries is called an oophorectomy. A hysterectomy does not cause menopause but removal of both ovaries (bilateral oophorectomy) does cause immediate menopause.

Doctors may recommend hormone therapy for certain women. Hormone therapy for a woman who has her uterus uses a combination of estrogen and progestin because estrogen alone increases the risk for endometrial (uterine) cancer. However, women who have had their uteruses removed do not have this risk and can take estrogen alone, without the progestin.

Some evidence suggests that surgically cutting the pain-conducting nerve fibers leading from the uterus diminishes the pain from dysmenorrhea. Two procedures, laparascopic uterine nerve ablation (LUNA) and laparoscopic presacral neurectomy (LPSN), can block such nerves.

Some small studies have shown benefits from these procedures, but stronger evidence is needed before they can be recommended for women with severe primary dysmenorrhea or the chronic pelvic pain associated with endometriosis.

Resources

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists -- www.acog.org

- National Infertility Association -- resolve.org

- American Society for Reproductive Medicine -- www.asrm.com

- Endometriosis Association -- endometriosisassn.org

References

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 110: noncontraceptive uses of hormonal contraceptives. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(1):206-218. PMID: 20027071 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20027071.

Bofill Rodriguez M, Lethaby A, Grigore M, et al. Endometrial resection and ablation techniques for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;1:CD001501. PMID: 30667064 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30667064.

Bulun SE. Physiology and pathology of the female reproductive axis. In: Melmed S, Auchus RJ, Goldfine AB, Koenig RJ, Rosen CJ, eds. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 14th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 17.

Davies J, Kadir RA. Heavy menstrual bleeding: An update on management. Thromb Res. 2017;151(Suppl 1):S70-S77. PMID: 28262240 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28262240.

Fergusson RJ, Bofill Rodriguez M, Lethaby A, Farquhar C. Endometrial resection and ablation versus hysterectomy for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;8:CD000329. PMID: 31463964 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31463964.

Haamid F, Sass AE, Dietrich JE. Heavy Menstrual Bleeding in Adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2017;30(3):335-340. PMID: 28108214 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28108214.

Lethaby A, Duckitt K, Farquhar C. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(1):CD000400. PMID: 23440779 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23440779.

Lethaby A, Hussain M, Rishworth JR, Rees MC. Progesterone or progestogen-releasing intrauterine systems for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(4):CD002126. PMID: 25924648 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25924648.

Levy-Zauberman Y, Pourcelot AG, Capmas P, Fernandez H. Update on the management of abnormal uterine bleeding. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2017;46(8):613-622. PMID: 28716637 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28716637.

Lobo RA. Primary and secondary amenorrhea and precocious puberty: etiology, diagnostic evaluation, management. In: Lobo RA, Lentz G, Gershenson D, Lentz GM, Valea FA, eds. Comprehensive Gynecology. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017:chap 38.

Magowan BA, Owen P, Thomson A. Heavy menstrual bleeding, dysmenorrhea and premenstrual syndrome. In: Magowan BA, Owen P, Thomson A, eds. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2019:chap 7.

Marjoribanks J, Lethaby A, Farquhar C. Surgery versus medical therapy for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(1):CD003855. PMID: 26820670 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26820670.

Osayande AS, Mehulic S. Diagnosis and initial management of dysmenorrhea. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89(5):341-346. PMID: 24695505 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24695505.

Ryntz T, Lobo RA. Abnormal uterine bleeding: etiology and management of acute and chronic excessive bleeding. In: Lobo RA, Lentz G, Gershenson D, Lentz GM, Valea FA, eds. Comprehensive Gynecology. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017:chap 26.

Singh S, Best C, Dunn S, Leyland N, Wolfman WL. No. 292-Abnormal uterine bleeding in pre-menopausal women. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018;40(5):e391-e415. PMID: 29731212 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29731212.

Smith CA, Armour M, Zhu X, Li X, Lu ZY, Song J. Acupuncture for dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4:CD007854. PMID: 27087494 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27087494.

Sweet MG, Schmidt-Dalton TA, Weiss PM, Madsen KP. Evaluation and management of abnormal uterine bleeding in premenopausal women. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85(1):35-43. PMID: 22230306 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22230306.

Upadhya KK, Sucato GS. Menstrual problems. In: Kliegman RM, St Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 142.

Whitaker L, Critchley HO. Abnormal uterine bleeding. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;34:54-65. PMID: 26803558 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26803558.

Reviewed By: John D. Jacobson, MD, Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Loma Linda University School of Medicine, Loma Linda Center for Fertility, Loma Linda, CA. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.

© 1997- A.D.A.M., a business unit of Ebix, Inc. Any duplication or distribution of the information contained herein is strictly prohibited.