Headaches - cluster - InDepth

Highlights

Cluster headaches are one of the most painful types of headache. They are marked by excruciating, stabbing, and penetrating pain, which is usually centered around the eye. Cluster headache attacks occur very suddenly and without warning, with the pain peaking within 15 minutes.

In addition to pain, symptoms of cluster headaches may include:

- Swollen or droopy eyelid

- Watery, tearing eye

- Stuffy or runny nose

- Contracted eye pupil

- Forehead and facial sweating

- Intolerance to light and sound

- Cluster headaches are rare, affecting less than 1% of the population.

- Men are much more likely to suffer from cluster headaches than women.

- Many people who have cluster headaches have a personal or family history of migraine headaches.

Treatment of cluster headaches focuses on relieving pain when attacks occur, and on preventive strategies to reduce attack duration and frequency. Oxygen therapy and injections of sumatriptan (Imitrex, generic) are the most effective treatments for acute attacks. Verapamil (Calan, generic), a drug for high blood pressure, is typically the first choice of medication used for long-term prevention. A new injectable drug (galcanezumab, Emgality) has recently been approved by the FDA for episodic cluster headache prevention.

Behavioral treatments can be a helpful supplement to drug therapy. These treatments include relaxation therapy, biofeedback, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and stress management. People should also identify and avoid any triggers, such as alcohol use and cigarette smoking, which may provoke cluster headache attacks.

Results from the US Cluster Headache Survey, the largest study of Americans with cluster headache, reveal:

- Diagnostic delays. Many people with cluster headache experience at least a 5-year delay in having their symptoms correctly diagnosed as cluster headache. Only 21% of survey respondents reported a correct initial diagnosis. Sinusitis and migraine were common misdiagnoses.

- Suicidal thoughts. More than half (55%) of respondents reported experiencing suicidal thoughts.

- Time of attacks. Most cluster headache attacks occur between early evening and early morning hours, with a peak time of midnight to 3 a.m.

- Triggers. Alcohol, especially beer, is the most common trigger of attacks, followed by weather changes and smells.

Introduction

Cluster headaches are among the most painful, and least common, of all headaches. The pain can be so excruciating that they are sometimes referred to as "suicide headaches." Their signature is a pattern of periodic cycles ("clusters") of headache attacks, which may be either:

- Episodic. Attacks recur frequently for weeks or months, separated by long pain-free periods that last months or years. About 90% of people with cluster headache experience episodic cycles.

- Chronic. Attacks occur regularly for more than 1 year, with pain-free periods lasting less than 1 month. Only about 10% of people with cluster type headache have chronic cluster headaches. The chronic form is very difficult to treat.

Timing of an Attack

Cluster headache attacks tend to occur with great regularity at the same time of day. (For this reason, cluster headaches are sometimes referred to as "alarm clock" headaches.) Most attacks occur during the night or within a few hours after falling asleep, with peak time of midnight to 3 a.m.

Duration of an Attack

A single cluster attack is usually brief but extremely painful. The pain peaks in about 5 to 15 minutes and then lingers for 15 to 180 minutes if left untreated.

Number of Attacks Per Day

During an active cycle, people can experience as few as 1 attack every other day to as many as 8 attacks a day.

Duration of Cycles

Attack cycles typically last 6 to 12 weeks with remissions lasting up to 1 year. In the chronic form, attacks are ongoing, and there is little remission. Many people experience initially 1 to 2 attack periods a year. The attack cycles then tend to occur seasonally, most often in the spring and autumn.

Cluster headaches are a type of primary headache. A headache is considered primary when it is not caused by another disease or medical condition. The most common types of primary headaches are migraine and tension-type. Cluster headaches are considered a rare type of primary headache.

Cluster headache belongs to a group of primary headaches called trigeminal autonomic cephalgias (TACs). TACs share certain characteristics such as pain on one side of the head, eye watering, nasal congestion, and short duration of symptoms.

Other TACs that resemble cluster headache include:

- Paroxysmal Hemicrania. Paroxysmal hemicrania is very similar to cluster headache. It causes multiple, short, and severe daily headaches with symptoms resembling those of cluster headache. As compared to cluster headaches, the attacks are shorter (1 to 2 minutes) and more frequent (occurring an average of 9 to 15 times a day). This headache is even rarer than cluster headache, tends to occur more often in women, and responds to treatment with the anti-inflammatory drug indomethacin (Indocin, generic).

- SUNCT Syndrome. SUNCT syndrome (short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks with conjunctival injection and tearing) causes stabbing or burning eye pain that may resemble cluster headaches, but attacks are very brief (lasting about a minute) and may occur more than 100 times per day. Red and watery eyes, sweating forehead, and congestion are typical. This rare headache is more common in men than women and does not respond to usual headache treatments.

- Hemicrania Continua. Hemicrania continua is not a TAC type of headache but it produces some symptoms that are similar to cluster headache. The pain occurs continuously on one side of the face and is typically of mild-to-moderate intensity with some instances of severe pain. Unlike cluster headache attacks, which do not last long, attacks of hemicrania continua can last from days to weeks, with constant moderate-to-severe pain. Hemicrania continua is more common in women than in men. It is treated with indomethacin.

Causes

The cause of cluster headaches is unknown. They are likely due to an interaction of abnormalities in the blood vessels, nerves, and chemicals that affect regions in the face.

Evidence strongly suggests that abnormalities in the hypothalamus, a complex structure located deep in the brain, play a major role in cluster headaches. Advanced imaging techniques have shown that a specific area in the hypothalamus is activated during a cluster headache attack.

The hypothalamus is involved in the regulation of many important chemicals and nerve pathways, including:

- Nerve clusters that regulate the body's biologic rhythms (its circadian rhythms).

- Serotonin and norepinephrine. These are neurotransmitters (chemical messengers in the brain) that are involved with well-being and appetite.

- Cortisol (stress hormone).

- Melatonin (a hormone related to the body's response to light and dark).

- Beta-endorphins (substances that modulate pain).

Circadian Abnormalities

Cluster attacks often occur during specific sleep stages. They also often follow the seasonal increase in warmth and light. Many people report an increase in attacks when daylight savings time changes occur in the fall and spring. Researchers have focused attention on circadian rhythms, and in particular small clusters of nerves in the hypothalamus that act like biologic clocks. The hormone melatonin is also involved in the body's biologic rhythms.

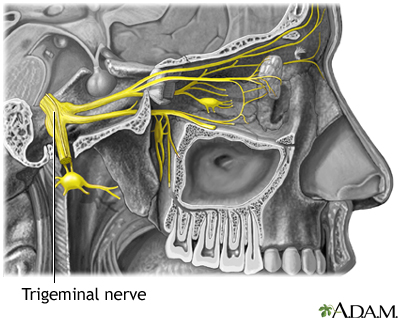

The trigeminal nerve carries sensations from the face to the brain along a nerve pathway. Activation of the trigeminal nerve causes the eye pain associated with cluster headaches. The parasympathetic autonomic system regulates non-voluntary actions in the body, such as secretions, heart rate, and blood vessel activity. When the trigeminal nerve stimulates the autonomic system it causes cluster headache symptoms such as eye tearing and nasal congestion.

Cluster headaches are associated with dilation (widening) of blood vessels and inflammation of nerves behind the eye.

Cluster headaches may be caused by blood vessel dilation in the eye area. Inflammation of nearby nerves may give rise to the distinctive stabbing, throbbing pain usually felt in one eye. The trigeminal nerves branch off the brainstem behind the eyes and send impulses throughout the cranium and face.

What causes these events and how they relate to cluster headaches are still unclear. Because blood vessel dilation appears to follow, not precede, the pain, some action originating in the brain is likely to be part of the process.

Complications

The pain of cluster headaches can be intolerable. Fortunately, as people age, the attacks tend to cease, although no one can predict when they will end.

Anxiety and depression are common among people with cluster headaches, which can affect functioning and quality of life. The pain can be so intense that some people consider, or attempt, suicide.

Nighttime attacks can interfere with sleep and lead to sleep deprivation. Lack of sleep can increase the risk for depression, and other physical and emotional problems.

Some people with cluster headaches experience migraine-like aura. Research suggests that headaches that are accompanied by aura may increase the risk of stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA). TIA symptoms are similar to those of stroke, but last only briefly. However, people who have had a TIA are at increased risk for later having a stroke. People with cluster headaches may have risk factors for stroke, such as smoking. However, there currently is no data that indicates a cluster headache increases the risk of stroke.

Risk Factors

Cluster headaches are rare, affecting less than 1% of the population.

Cluster headaches can affect all ages, from children to older people, but are most common from young adulthood through middle age. In men, the typical age of onset is in the 30s. In women, cluster headaches usually develop in the 60s.

Men are 3 to 4 times more likely to have cluster headaches than women, especially for chronic cluster. Unlike with migraines, fluctuations in estrogen and other female hormones do not appear to play a role in cluster headaches.

Lifestyle factors play a role in cluster headaches. They include:

- Drinking. Alcohol consumption is a major risk factor. Alcohol, especially red wine and beer, is the most common attack trigger during active periods of headaches.

- Smoking. Cigarette smoking and tobacco products are risk factors for cluster headaches. These headaches are more common in people who smoke. However, quitting smoking does not appear to stop attacks.

- Stress. Emotional stress and physical exertion are risk factors for triggering cluster headaches.

Cluster headache attacks often coincide with times of seasonal change, such as in spring or autumn. Changes associated with daylight savings during these times of year may alter the normal sleep-wake cycle and trigger attacks.

Cluster headaches tend to run in families, suggesting that a genetic component may be involved. Cluster headache may occur more commonly in people with a "type A" personality.

About half of people with cluster headache have a personal or family history of migraine. It is possible for people to have both kinds of headache.

Head injury with brain concussion appears to increase the risk of cluster headaches, although a causal relationship has not been proven.

Cluster headaches tend to occur during specific sleep stages and are associated with several sleep disorders, including narcolepsy, insomnia, restless legs syndrome, and sleep apnea.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a disorder in which a person temporarily stops breathing during the night, perhaps hundreds of times. In some people, OSA may trigger a cluster headache during the first few hours of sleep, making them susceptible to follow-up attacks during the following midday to afternoon periods.

The following conditions and substances may trigger cluster attacks:

- Alcohol and cigarette smoking

- Allergic rhinitis (hay fever)

- Weather changes

- High altitudes (trekking, air travel)

- Smells

- Bright light (including sunlight or flashing lights)

- Stress

- Physical exertion, including sexual activity

- Heat (hot weather, hot baths or showers)

- Certain medications (including those that cause blood vessel dilation, such as nitroglycerin, and various blood pressure medications)

- Cocaine

Triggers usually have an effect only during active cluster cycles. When the disorder is in remission, such triggers rarely set off the headaches.

Symptoms

Cluster headaches cause intense excruciating pain. The pain is located in, behind, or around the eye and is described as deep, constant, boring, stabbing, piercing, or burning. The pain may then spread to the forehead, temple, cheek, nose, and jaw.

The pain generally reaches very severe levels within 15 minutes with the attack lasting for 45 minutes to 3 hours (if left untreated). People may feel agitated or restless during an attack and often want to isolate themselves and then move around. This is different than migraine headaches, in which people tend to want to lie down in a quiet room. Gastrointestinal symptoms are not very common.

Cluster headaches usually strike suddenly and without warning. Some people experience a sensation of pressure in the affected side before an attack. Although rare, some people have a migraine-type aura before the attack.

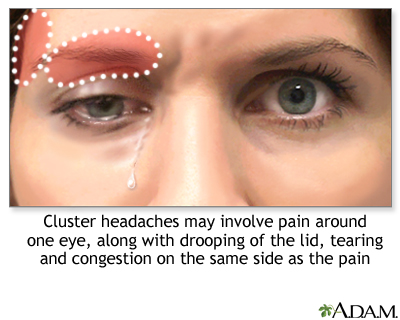

The pain and other facial symptoms of cluster headache always occur on one side of the head. In addition to pain, other typical symptoms include:

- Swollen or droopy eyelid

- Watery, tearing eye

- Contraction of the eye pupil

- Stuffy or runny nose

- Forehead and facial sweating

- Restlessness and agitation

- Nausea and vomiting

- Intolerance to light and sound

The symptoms of a cluster headache include stabbing severe pain behind or above one eye or in the temple. Tearing of the eye, congestion in the associated nostril, and pupil changes and eyelid drooping may also occur.

Diagnosis

Cluster headaches are diagnosed on the basis of signs and symptoms. Many people report a delay of more than 5 years in the diagnosis of their cluster headaches.

Migraine-like symptoms (light and sound sensitivity, nausea, and vomiting) are major reasons for frequent misdiagnosis. In some cases, people are inappropriately treated for other types of headaches (like migraine) or health conditions (like sinusitis).

Cluster headache is diagnosed by the pattern of recurrent attacks, and by typical symptoms (pain on one side of head, swollen eyelid, watery eye, and runny nose).

Keeping a headache diary to record a description of attacks can help your health care provider make an accurate diagnosis. You should describe to your provider:

- Frequency of attacks (if keeping a diary, record the date and time of each attack)

- Description of pain (stabbing, throbbing)

- Location of pain

- Duration of pain

- Intensity of pain (using a number scale)

- Associated symptoms (tearing eyes, nausea and vomiting, and sweating)

- Any measures that bring relief (applying pressure, going out for fresh air)

- Any events that preceded or may have triggered the attack

- Any medications you are taking

- Behaviors during a headache (restlessness, agitation)

The provider will ask about your medical history and perform a physical exam that will include looking at your head, neck, and eyes. The provider may perform a neurologic examination, which includes a series of simple exercises to test strength, reflexes, coordination, and sensation. Bringing pictures of you taken during a headache may help your provider.

In some cases, the provider may order an imaging test to check for brain abnormalities that may be causing the headaches. For imaging tests, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans are preferred over computed tomography (CT) scans because MRIs do not expose people to radiation.

As part of the diagnosis, the provider should rule out other headaches and disorders.

Migraines

Cluster headaches are often misdiagnosed as migraines but they are quite different based on:

- Frequency and Duration. Cluster headaches generally last 15 minutes to a few hours and can occur several times a day. A single migraine attack is continuous over the course of one or several days.

- Behavior. Cluster headache sufferers tend to move about while migraine sufferers usually want to lie down.

Nevertheless, both cluster headaches and migraine cause sensitivity to light and noise, which can make it difficult to distinguish between these two headaches.

Other Headaches

Other headaches that resemble cluster headaches include SUNCT (short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks with conjunctival injection and tearing) and paroxysmal hemicranias. Cluster headache may also resemble some secondary headaches notably trigeminal neuralgia, temporal arteritis, and sinus headaches. Cluster headache symptoms are usually precise enough to rule out these other types of headaches.

Tear in the Carotid Artery

A tear in the carotid artery (carotid artery dissection) can also lead to a droopy eye and small pupil. Dissection can interrupt blood flow to the brain and can lead to stroke. Risk factors for carotid dissection include trauma or connective tissue disorders.

Orbital Myositis

An unusual condition called orbital myositis, which produces swelling of the muscles around the eye, may mimic symptoms of a cluster headache. This condition should be considered in people who have unusual symptoms such as protrusion of the eyeball, painful eye movements, or pain that does not dissipate within 3 hours.

Headaches indicating a serious underlying problem, such as cerebrovascular disorder or malignant hypertension, are uncommon. (A headache without other neurological symptoms is not a common symptom of a brain tumor.) People with existing long-term (chronic) headaches may, however, miss a more serious condition believing it to be one of their usual headaches.

You should contact your provider if the quality of a headache or accompanying symptoms has changed. Be sure to call 911 or your local emergency number, your provider, or go to an emergency room for any of the following symptoms:

- Sudden, severe headache that persists or increases in intensity over the following hours, sometimes accompanied by nausea, vomiting, or altered mental states (possible indication of hemorrhagic stroke, which is also called brain hemorrhage).

- Sudden, very severe headache, worse than any headache ever experienced (possible indication of brain hemorrhage or a ruptured aneurysm).

- Chronic or severe headaches that begin after age 50.

- Headaches accompanied by other symptoms, such as memory loss, confusion, loss of balance, changes in speech or vision, or loss of strength in or numbness or tingling in arms or legs (possibility of stroke).

- Headaches after head injury, if drowsiness or nausea are present (possibility of brain hemorrhage).

- Headaches accompanied by fever, stiff neck, nausea and vomiting (possibility of meningitis).

- Headaches that increase with coughing or straining (possibility of brain swelling).

- A throbbing pain around or behind the eyes or in the forehead accompanied by redness in the eye and perceptions of halos or rings around lights (possibility of acute glaucoma).

- A one-sided headache in the temple in older people; the artery in the temple is firm and knotty and has no pulse; scalp is tender (possibility of temporal arteritis, which can cause blindness or stroke if not treated).

- Sudden onset and then persistent, throbbing pain around the eye that may spread to the ear or neck and is unrelieved by pain medication (possibility of blood clot in one of the sinus veins of the brain).

- New or changing headaches with a compromised immune system (such as from cancer or HIV).

Managing Cluster Headaches

Management of cluster headaches focuses on:

- Acute therapy for stopping an attack while it is happening

- Preventive therapy for stopping or reducing attack recurrences

The most effective and best-studied treatments for a cluster attack are:

- Oxygen inhalation.

- Triptan drugs. An injection of the triptan drug sumatriptan (Imitrex, generic) is the first-line cluster headache treatment. Intranasal formulations of sumatriptan or zolmitriptan (Zomig) are alternatives.

Relief can occur in 5 to 10 minutes. Oxygen and sumatriptan injection are sometimes given together.

Vagal nerve stimulation (VNS) is also used to treat acute episodic attacks.

Other drugs that may be used for acute attacks are nasal sprays of dihydroergotamine or lidocaine.

Cluster headache attacks are usually short, lasting from 15 minutes to 3 hours. The excruciating pain may have subsided by the time the person reaches a medical office or emergency room.

Because it can be difficult to treat attacks when they occur, treatment efforts focus on the prevention of attacks during cluster cycles. Although certain drugs are standard, preventive therapy needs to be individually tailored. Your provider may prescribe a combination of drugs.

Verapamil (Calan, generic), a calcium-channel blocker drug, is the mainstay preventive treatment for cluster headaches. However, it can take 2 to 3 weeks for this drug to take effect. During this period, corticosteroids (typically prednisone) may be used as an initial transitional therapy. For long-term treatment of chronic cluster headaches, lithium may be used as an alternative to verapamil.

Galcanezumab (Emgality), a calcitonin-gene related peptide (CGRP) antagonist, is a recently approved preventive treatment for episodic cluster headache. It is given as a monthly subcutaneous injection that can be self-administered.

Although they are not FDA-approved for cluster headache, anti-seizure drugs such as divalproex sodium (Depakote, generic) valproate sodium (Depacon, generic), valproic acid (Depakene, generic), topiramate (Topamax, generic), and gabapentin (Neurontin, generic) are sometimes used for preventive treatment.

Behavioral Treatments

Behavioral therapies are a helpful accompaniment to drug treatment. These approaches can help with pain management and enable people to feel more in control of their condition.

Behavioral approaches include:

- Relaxation treatment combined with biofeedback

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy

Lifestyle Changes

People should avoid the following triggers that may provoke cluster headache attacks:

- Alcohol. Heavy alcohol use is associated with cluster headaches.

- Cigarette smoking. A majority of people with cluster headaches are cigarette smokers. While studies have not shown that quitting cigarettes will stop cluster headaches, smoking cessation should still be a goal. Smokers who cannot quit should at least stop at the first sign of an attack and not smoke throughout a cycle of active headaches.

Treatment for Acute Attacks

Breathing pure oxygen (by face mask, for 15 minutes or less) is one of the most effective and safest treatments for cluster headache attacks. It is often the first choice treatment. Inhalation of oxygen raises blood oxygen levels, therefore relaxing narrowed blood vessels. Appropriate patients may benefit from having a portable oxygen tank in their home.

In some people, oxygen treatment only delays the attack by minutes or hours. In this case, oxygen therapy should be avoided, as it may actually increase the frequency of attacks.

Triptans are drugs that are usually used to treat migraine headaches. They can also help stop a cluster headache attack.

A subcutaneous injection of sumatriptan (Imitrex, generic) is the standard triptan treatment and is FDA-approved for cluster headaches. Sumatriptan injections usually work within 15 minutes.

The nasal spray form may also be effective for some people, and generally provides relief within 30 minutes. The spray seems to work best for attacks that last at least 45 minutes, although some people find it does not work as well as the injectable form.

Zolmitriptan (Zomig) is another triptan drug used for cluster headache treatment. It is given in either oral or nasal spray form. Zolmitriptan may have fewer side effects than sumatriptan.

Side Effects

Side effects of sumatriptan and other triptans may include:

- Nausea

- Dizziness

- Muscle weakness

- Heaviness or pressure in the chest

- Tingling and numbness in the toes

- Rapid heart rate

Complications and Contraindications of Triptans

The following are some potentially serious problems with triptans:

- Heart and Circulation Problems. Triptans narrow (constrict) blood vessels. Because of this action, spasms in the blood vessels may occur, which can cause stroke and heart attack. This is a rare but very serious side effect. People with a history of heart attack, stroke, angina, uncontrolled high blood pressure, peripheral artery disease, or heart disease should not use triptan drugs.

- Serotonin Syndrome. Serotonin syndrome is a life-threatening condition that occurs from an excess of the brain chemical serotonin. Triptans, as well as certain types of antidepressant medications, can increase serotonin levels. These antidepressants include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). It is important not to combine a triptan drug with an SSRI or SNRI drug. Serotonin syndrome is most likely to occur when starting or increasing the dose of a triptan or antidepressant. Symptoms include restlessness, hallucinations, rapid heartbeat, tremors, increased body temperature, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting. You should seek immediate medical care if you have these symptoms.

Injections of the ergotamine-derived drug dihydroergotamine (DHE, Migranal) can often stop cluster attacks within 5 minutes, offering benefits similar to injectable sumatriptan. Ergotamine is also available in the form of a nasal spray, rectal suppositories, and tablets.

Ergotamine can have dangerous drug interactions with many medications, including sumatriptan. All ergotamine products approved by the FDA contain a "black box" warning in the prescription label explaining these drug interactions. Because ergotamine constricts blood vessels, people with peripheral vascular disease should not use this drug.

Lidocaine, a local anesthetic, is applied to the affected nostril in nasal spray or nasal-drop form. It usually takes effect within a few minutes and can help temporarily stop pain by numbing part of the trigeminal nerve.

Capsaicin is a compound derived from hot pepper. Some people who have not found relief through other medications use it to treat or prevent cluster headaches by applying it intranasally. There have been few studies to confirm its effectiveness. It can cause an intense burning sensation.

Preventive Medications

Calcium-channel blockers, commonly used to treat high blood pressure and heart disease, are important drugs for preventing episodic and chronic cluster headaches. Verapamil (Calan, generic) is the standard calcium-channel blocker used for cluster headache prevention. It can take 2 to 3 weeks to have a full effect, and a corticosteroid drug may be used in combination during this transitional period. Constipation is a common side effect.

People taking calcium-channel blockers should not stop taking the drug abruptly. Doing so can dangerously increase blood pressure. Overdose can cause dangerously low blood pressure and slow heartbeats.

Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) causes blood vessel relaxation and is involved in sensing of pain. CGRP antagonists have long been investigated as potential treatments for migraine and recently three drugs targeting CGRP have been approved by the FDA for prevention of migraine. Of them, galcanezumab (Emgality) has also been approved as a preventive treatment for episodic cluster headache. Galcanezumab reduces the frequency of attacks in people with cluster headache. It is given as a monthly subcutaneous injection that can be self-administered.

Lithium (Eskalith, generic), commonly used for bipolar disorder, may also help prevent cluster headaches. The benefits of lithium usually appear within 2 weeks of starting the drug, and often within the first week. Lithium may be used alone or with other drugs. Lithium can have many side effects including trembling hands, nausea, and increased thirst. Weight gain is a common side effect with long-term use.

Corticosteroid (steroid) drugs are very useful as transitional drugs for stabilizing people after an attack until a maintenance drug, such as verapamil, begins to take effect. Prednisone (generic) and dexamethasone (Decadron, generic) are the standard steroid drugs used for short-term transitional treatment.

These drugs are typically taken for a week and then gradually tapered off. If headaches return, the person may start taking the steroid again. Unfortunately, long-term use of oral steroids can lead to serious side effects so they cannot be taken for on-going prevention. Serious side effects, such as avascular necrosis of the joints, may occur even with limited use of steroids. Other short term side effects include restlessness/irritability, elevation in blood sugar or blood pressure, low potassium (hypokalemia) and gastric irritation.

Steroid injections may also provide short-term relief. Some people are helped by an occipital nerve block in which an anesthetic and a corticosteroid are injected into the occipital nerve in the back of the head. Researchers are also investigating suboccipital injections where a steroid is injected into the base of the skull on the same side as the headache attack.

Anti-seizure drugs, which are used for epilepsy treatment, may be helpful for preventing cluster headaches. They include older drugs such as divalproex (Depakote, generic), valproate (Depacon, generic), and valproic acid (Depakene, generic) and newer drugs such as topiramate (Topamax, generic) and gabapentin (Neurontin, generic). More research needs to be done to evaluate how effective these drugs are at preventing cluster headaches.

These drugs can have significant side effects. Some anti-seizure drugs, particularly valproate products, can increase the risk for birth defects and should not be taken by pregnant women. All women of child-bearing potential should take special precautions due to increased risk of birth defects, should they become pregnant while taking any anti-seizure drug. All anti-seizure drugs can increase the risks of suicidal thoughts and behavior (suicidality).

Botulinum

Botulinum toxin A (Botox) injections are typically used to reduce abnormal muscle contractions, such as may be seen in spasticity, various movement disorders (dystonia, blepharospasm) and to treat abnormal sweating, in addition to smooth wrinkles. Botulinum toxin is also being studied for treatment of headaches, and is approved for prevention of chronic migraine. Research on its use for cluster headache prevention is still preliminary, and there is little evidence to support its effectiveness.

Melatonin

Melatonin is a brain hormone that helps to regulate the sleep-wake cycle and adjust the body's internal clock. Some research suggests that melatonin supplements may help prevent episodic or chronic cluster headaches. Supplements are made from a synthetic chemical melatonin that is produced in a lab. Melatonin supplements are sold in health food stores, but as with most natural remedies, the quality of different preparations varies. More studies are needed to confirm effectiveness and dosage.

Hyperbaric oxygen

Only a few small studies have evaluated hyperbaric oxygen for treatment of an acute cluster headache. In addition to limited availability and expense, there currently is no evidence to show hyperbaric oxygen is more effective than traditional oxygen.

Octreotide (Sandostatin) and somatostatin

These related drugs have weak supporting evidence to support their use.

Surgery

Surgery may be considered as a last resort for chronic cluster headaches that do not respond to other treatments. People whose headaches have not gone into remission for at least a year may also be candidates for surgery.

Most surgical approaches for cluster headaches are still considered experimental, having been tested on only a relatively small number of people. In general, surgery for cluster headaches has limited success and can have distressing side effects. However, some surgical techniques, such as deep brain electrical stimulation, are showing promise.

A number of implantable electrical stimulation devices are being studied as treatments for chronic cluster headaches that do not improve with drug treatment. These work on specific nerve tissues, such as peripheral nerves, the sphenopalatine ganglion (SPG), occipital nerve, or high cervical spinal cord. Preliminary results are encouraging, but larger studies are necessary for most of these devices.

Deep brain stimulation (also called neurostimulation) may relieve chronic cluster headaches that do not respond to drug therapy. A similar technique is approved for treating the tremors associated with Parkinson disease. The surgeon implants a tiny wire in a specific part of the hypothalamus. The wire receives electrical pulses from a small generator implanted under the collarbone.

Although only a small number of people have been treated, results to date are promising. Some people have remained completely free of pain for an average of more than 7 months when the device is switched on. When the device is turned off, headaches reappear within days to weeks. The procedure is reversible and appears to be generally safe, although a few cases of fatal cerebral hemorrhage have occurred. There are other risks of this surgery, such as infection. Patients with these implanted wires and stimulator may be at great risk of injury if subjected to an MRI scan.

In very preliminary research, spinal cord stimulators have shown promising results in patients with cluster headache. As these devices are prone to complications, they are not recommended for routine use until more research can be done.Occipital nerve stimulation is being investigated as a less invasive and less risky alternative to deep brain hypothalamus stimulation. Recent studies have reported promising results in a small number of people with cluster headaches. Some subjects became pain-free, while others had reduced frequency of headache attacks.

The vagus nerve runs between the brain and the abdomen. Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) is approved by the FDA to treat episodic cluster headache. Electrodes provide electrical impulses to the vagal nerve through the skin.

Nerve fibers in the sphenopalatine area (deep between the nose and the skull) transmit signals that may contribute to cluster headache pain. Very early research has shown that electrical stimulation of these nerve endings can reduce frequency of attacks in many patients. More studies are necessary.

Percutaneous Radiofrequency Retrogasserian Rhizotomy (PRFR)

PRFR generates heat to destroy pain-carrying nerve fibers in the face. Unfortunately, complications are common and may include numbness, weakness during chewing, changes in tearing and salivation, and facial pain. In severe, but rare, cases, complications include damage to the cornea and vision loss.

Percutaneous Retrogasserian Glycerol Rhizolysis (PRGR)

PRGR is a less invasive technique than PRFR and has fewer complications. It involves injections of glycerol to block the facial nerves that cause the pain. Cluster headaches usually recur.

Microvascular Decompression of the Trigeminal Nerve

Microvascular decompression frees the trigeminal nerve from any blood vessels that are pressing against it. The procedure is risky, and possible complications include nerve and blood vessel injury and spinal fluid leakage. This can be helpful for treating trigeminal neuralgia, but there is reasonably good evidence that it is not effective for treatment of cluster headaches.

Resources

- National Headache Foundation -- www.headaches.org

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke -- www.ninds.nih.gov

- American Migraine Foundation -- americanmigrainefoundation.org

- American Academy of Neurology -- www.aan.com

- Cluster Busters -- clusterbusters.org

References

Ashina H, Newman L, Ashina S. Calcitonin gene-related peptide antagonism and cluster headache: an emerging new treatment. Neurol Sci. 2017;38(12):2089-2093. PMID: 28856479 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28856479.

Bennett MH, French C, Schnabel A, Wasiak J, Kranke P, Weibel S. Normobaric and hyperbaric oxygen therapy for the treatment and prevention of migraine and cluster headache. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(12):CD005219. PMID: 26709672 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26709672.

Digre KB. Headaches and other head pain. In: Goldman L, Schafer AI, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 26th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2020:chap 370.

D'Ostilio K, Magis D. Invasive and non-invasive electrical pericranial nerve stimulation for the treatment of chronic primary headaches. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2016;20(11):61. PMID: 27678260 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27678260.

Fischera M, Marziniak M, Gralow I, Evers S. The incidence and prevalence of cluster headache: a meta-analysis of population-based studies. Cephalalgia. 2008;28(6):614-8. PMID: 18422717 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18422717.

Garza I, Schwedt TJ, Robertson CE, Smith JH. Headache and other craniofacial pain. In: Daroff RB, Jankovic J, Mazziotta JC, Pomeroy SL, eds. Bradley's Neurology in Clinical Practice. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:chap 103.

Gelfand AA, Goadsby PJ. The role of melatonin in the treatment of primary headache disorders. Headache. 2016;56(8):1257-1266. PMID: 27316772 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27316772.

Goodfriend SD, Tadi P, Koury R. Carotid Artery Dissection. [Updated 2020 Mar 30]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430835/

Hershey AD, Kabbouche MA, O'Brien HL, Kacperski J. Headaches. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 613.

Hoffmann J, May A. Diagnosis, pathophysiology, and management of cluster headache. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(1):75-83. PMID:29174963 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29174963.

Holle-Lee D, Gaul C. Noninvasive vagus nerve stimulation in the management of cluster headache: clinical evidence and practical experience. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2016;9(3):230–234. PMID: 27134678 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27134678.

Khan S, Olesen A, Ashina M. CGRP, a target for preventive therapy in migraine and cluster headache: systematic review of clinical data. Cephalalgia. 2017:333102417741297. PMID: 29110503 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29110503.

Láinez MJ, Guillamón E. Cluster headache and other TACs: pathophysiology and neurostimulation options. Headache. 2017;57(2):327-335. PMID: 28128461 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28128461.

May A, Schwedt TJ, Magis D, et al. Cluster headache. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:18006. PMID: 29493566 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29493566.

Muñoz I, Hernández MS, Santos S. Personality traits in patients with cluster headache: a comparison with migraine patients. J Headache Pain. 2016;17:25. PMID: 26975362 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26975362.

Rizzoli P, Mullally WJ. Headache. Am J Med. 2018;131(1):17-24. PMID: 28939471 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28939471.

Robbins MS, Starling AJ, Pringsheim TM, Becker WJ, Schwedt TJ. Treatment of cluster headache: the American Headache Society evidence-based guidelines. Headache. 2016;56(7):1093-1106. PMID: 27432623 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27432623.

Schuster NM, Rapoport AM. New strategies for the treatment and prevention of primary headache disorders. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12(11):635-650. PMID: 27786243 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27786243.

Vyas DB, Ho AL, Dadey DY. Deep Brain Stimulation for Chronic Cluster Headache: A Review. Neuromodulation. 2019;22(4):388-397. PMID: 30303584 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30303584.

Yuan H, Spare NM, Silberstein SD. Targeting CGRP for the Prevention of Migraine and Cluster Headache: A Narrative Review. Headache. 2019;59 Suppl 2:20-32. PMID: 31291020 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31291020.

Reviewed By: Joseph V. Campellone, MD, Department of Neurology, Cooper Medical School at Rowan University, Camden, NJ. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.