Restless legs syndrome and related disorders - InDepth

Highlights

Overview

- Restless legs syndrome (RLS) is a condition in which one has feelings of "pulling, searing, drawing, tingling, bubbling, or crawling" beneath the skin, usually in the calf area. This causes an irresistible urge to move the legs. The sensations can also affect the thighs, feet, and sometimes, even the arms.

- It can be a temporary problem (such as during pregnancy or while taking antidepressant medication) or a chronic, long-term issue. It can develop from several medical conditions and genetic risk factors.

RLS and PLMD

- Periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD) often accompanies RLS. It is a condition where leg muscles contract and jerk every 20 to 40 seconds during sleep. These movements may last less than 1 second, or as long as 10 seconds.

- Unlike RLS, contractions in PLMD usually do not wake people, although bed partners may be wakened by the movements.

- Four out of five people who have RLS also report having PLMD, but only about a third of people with PLMD also have RLS.

Treatment

- Treatment often includes over-the-counter medicines, lifestyle changes, or iron supplements, in cases where a lack of iron has been identified. Prescription medications can provide good relief of frequent or severe symptoms.

- Drugs to treat RLS include dopaminergic agonists, hypnotics, opioids, nonopioids, antiepileptic drugs, antidepressants, and others. Only a few drugs are FDA approved to treat RLS (ropinirole, pramipexole, rotigotine, gabapentin enacarbil). The rest are used off-label. Medicine is carefully chosen based on the intensity and duration of symptoms.

- Long-term treatment with dopaminergic agonists can lead to tolerance (reduced response over time) and augmentation (worsening of symptoms with ongoing treatment).

Introduction

Restless legs syndrome (RLS) is a poorly understood movement disorder that affects 3% to 15% of the general population. The problem can occur in both children and adults, but it is found more in the older population. Although effective treatments are available, RLS often goes undiagnosed.

Symptoms of RLS

The core symptom of RLS is an irresistible urge to move the legs. Some people describe this symptom as a sense of unease and weariness in the lower leg. The sensations are aggravated by rest and relieved by movement. Specific characteristics of RLS include:

- Uncomfortable feelings of "pulling, searing, drawing, tingling, bubbling, or crawling" beneath the skin, usually in the calf area, causing an irresistible urge to move the legs. These sensations occur mostly in the lower legs, but they can sometimes affect the thighs, feet, and even in the arms. These may be the first symptoms of RLS in some people.

- Semi-rhythmic movements during sleep known as periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD), which occurs in about 4 out of 5 patients with RLS. See description below.

- Itching and pain, particularly aching pain.

- Symptoms usually occur at night when people are most relaxed, with their legs at rest, lying down. In more severe cases, symptoms also occur during the day while sitting. Movement relieves the symptoms.

- RLS episodes usually occur between 10 p.m. and 4 a.m. Symptoms are often worse shortly after midnight and disappear by morning. If the condition becomes more severe, people may begin to have symptoms during the day, but the problem is always worse at night.

- Disturbed nighttime sleep due to the unpleasant sensations and strong urge to move the legs. Resisting the urge to move the legs usually leads to tension build up until the legs jerk uncontrollably. People who experience daytime symptoms may find it difficult to sit during air or car travel, or through classes or meetings. People may feel excessively tired during the daytime as a result of inadequate or poor sleep.

Late-onset and Early-onset Forms

Restless Legs Syndrome can be either an early-onset or late-onset form of the syndrome. Each form may have different characteristics:

- People with early-onset RLS (occurring in the teenage years or earlier) tend to have a family history of the disorder. They usually have RLS without accompanying pain. Early-onset RLS is more common in women than in men.

- People with late-onset RLS usually do not have a family history of RLS. The condition is more likely to result from a problem with the nervous system. Symptoms may also include pain in the lower legs.

Periodic Limb Movement Disorder

Periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD) is also known as nocturnal myoclonus. Characteristics of PLMD include:

- Nighttime episodes that usually peak near midnight (similar to RLS).

- Contractions and jerking of the leg muscles every 20 to 40 seconds during sleep. These movements may last less than 1 second, or as long as 10 seconds.

- Movements of PLMD do not wake the person who actually has it, but they are often noticed by their bed partner. This condition is distinct from the brief and sudden movements that occur just as people are falling asleep, which can interrupt sleep.

- Association with RLS: Four out of five people who have RLS also report having PLMD, but only a third of people with PLMD report having RLS.

While treatments for the two conditions are similar, PLMD is a separate syndrome. PLMD is also very common in narcolepsy, a sleep disorder that causes people to fall asleep suddenly and uncontrollably.

Causes

The main cause of RLS is unknown. Scientists are researching nervous system problems that may arise in either the spinal cord or the brain. One theory suggests that low levels of the brain chemical dopamine cause RLS.

RLS may often have a genetic basis, particularly in those who develop it before age 40. RLS in older adults is less likely to be inherited.

The causes of PLMD are not clear. Some research suggests that it may be due to abnormalities in the autonomic nervous system, which regulates the involuntary actions of the smooth muscles, heart, and glands.

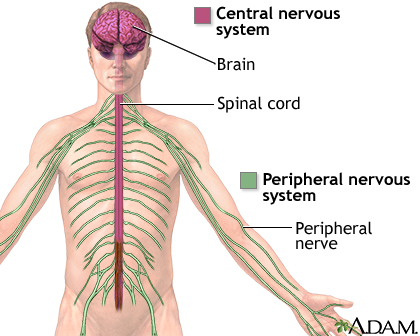

The central nervous system includes the brain and spinal cord. The peripheral nervous system includes nerves outside the brain and spinal cord.

Genetic Factors

People with RLS often have a family history of the disorder. There are at least six genetic factors that may play a part. Two of the genes are linked to spinal cord development. However, more research is needed to show a link between these genetic factors and dopamine or iron-regulating systems.

Neurological Abnormalities

Dopamine and Neurologic Abnormalities in the Brain

Several studies support the theory that an imbalance in neurotransmitters (chemical messengers in the brain), notably dopamine, may play a part in RLS. Dopamine triggers numerous nerve impulses that affect muscle movement. The effect is similar to that seen in Parkinson disease. In addition, drugs that increase dopamine levels treat both disorders. However, Parkinson disease itself does not seem to increase the risk for RLS and RLS early in life does not increase the risk of Parkinson later on.

Neurologic Abnormalities in the Spine

Other research suggests that RLS may be due to nerve impairment in the spinal cord. Researchers had thought that such abnormalities began in nerve pathways in the lower spine. However, some patients with RLS have symptoms in the arms, which indicates that the upper spine may also be involved.

Neuropathy

A disorder of the peripheral nerves is known as neuropathy. RLS may be more common in some forms of neuropathy, especially neuropathy that one is born with (hereditary neuropathy). Some experts suggest that RLS, particularly if it occurs in older adults, may be a form of neuropathy, which is an abnormality in the nervous system outside the spine and brain. So far, there is no evidence to support a cause and effect relationship between neuropathy and RLS. Neuropathy due to other medical problems like diabetes is also associated with increased risk of RLS.

Abnormalities of Iron Metabolism

Iron deficiency, even at a level too mild to cause anemia, has been linked to RLS in some people. Some research suggests that RLS in some people may be due to a problem with getting iron into cells that regulate dopamine in the brain. Some studies have reported RLS in a quarter to a third of people with low iron levels.

Deficiencies in Cortisol

Other research suggests that low levels of the hormone cortisol in the evening and early night hours may be related to RLS. Low-dose cortisol injections have reduced symptoms in some people.

Uremia or Kidney Failure

As many as 25% of people with chronic kidney disease have RLS. The exact cause of this is not known but may be related to co-existing anemia and iron deficiency as above. A loss of opioid receptors in the brain may also contribute to RLS in those with kidney disease.

Risk Factors

RLS may affect 3% to 15% of the general population. It is more common in women than in men. In North America and Europe, its frequency increases with age.

Family History

As many as two-thirds of people with RLS have a family history of the disorder and are more likely to develop RLS before they turn 40. People who develop the condition at a later age are less likely to have a family history of RLS. RLS is also more common in people from northern and western Europe, adding support for the theory that some cases have a genetic basis.

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

There is significant overlap between some of the symptoms and treatments for RLS and attention deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD). Up to a quarter of children diagnosed with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) may also have RLS, sleep apnea, or PLMD. These conditions may actually contribute to inattentiveness and hyperactivity. The disorders have much in common, including poor sleep habits, twitching, and the need to get up suddenly and walk about frequently. Some evidence suggests that the link between the diseases may be a deficiency in the brain chemical dopamine.

Pregnancy

About 1 in 5 pregnant women reports having RLS. The condition usually goes away within a month of delivery. RLS in pregnancy has been linked to deficiencies in iron and the B-group vitamin folate.

Dialysis

RLS is relatively common in people with chronic kidney disease undergoing kidney dialysis. Up to two-thirds of patients report this problem. Symptoms often disappear after a kidney transplant.

Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety can cause restlessness and agitation at night. These symptoms can cause RLS or strongly resemble the condition.

Other Conditions Associated with Restless Legs Syndrome

The following medical conditions are also associated with RLS, although the relationships are not clear. In some cases, these conditions may contribute to RLS. Others may have a common cause, or they may coexist due to other risk factors:

Osteoarthritis (degenerative joint disease).

About three-quarters of patients with RLS also have osteoarthritis, a common condition affecting older adults.Varicose veins.

Varicose veins occur in about 1 in 7 patients with RLS.- Obesity.

Diabetes.

People with type 2 diabetes may have higher rates of secondary RLS. Nerve pain (neuropathy) related to their diabetes cannot fully explain the higher rate of RLS.- Hypertension (high blood pressure).

- Hypothyroidism.

- Fibromyalgia.

- Rheumatoid arthritis.

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

- Chronic alcoholism.

- Sleep apnea (pauses in breathing during sleep) and snoring.

- Chronic headaches.

- Brain or spinal injuries.

Many muscle and nerve disorders.

Of particular interest is hereditary ataxia, a group of genetic diseases that affects the central nervous system and causes loss of motor control. Researchers believe that hereditary ataxia may supply clues to the genetic causes of RLS.- Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

- Psychiatric disorders, such as depression.

Environmental and Dietary Factors

The following environmental and dietary factors can trigger or worsen RLS:

- Iron deficiency. People who are deficient in iron are at risk for RLS, even if they do not have anemia.

- Folic acid or magnesium deficiencies.

- Smoking.

- Alcohol abuse.

- Caffeine. Coffee drinking is specifically associated with PLMD.

- Stress.

- Fatigue.

- Prolonged exposure to cold.

Medications

Drugs that may worsen or provoke RLS include:

- Antidepressants

- Antipsychotic drugs

- Anti-nausea drugs

- Calcium channel blockers (mostly used to treat high blood pressure)

- Metoclopramide (used to treat various digestive diseases)

- Antihistamines

- Oral decongestants

- Diuretics

- Asthma drugs

- Spinal anesthesia (anesthesia-induced RLS typically disappears on its own within several months)

Risk Factors for Periodic Limb Movement Disorder

About 6% of the general population has PLMD. However, the prevalence in older adults is much higher, reaching almost 60%. Studies suggest that PLMD may be especially common in older women. As with RLS, there are many conditions that are associated with PLMD. They include sleep apnea, spinal cord injuries, stroke, narcolepsy, and diseases that destroy nerves or the brain over time. Certain drugs, including some antidepressants and anti-seizure medications, may also contribute to PLMD. About a third of people with PLMD also have RLS.

Complications

RLS rarely results in any serious consequences. However, recurring severe symptoms may cause mental distress, loss of sleep, and daytime sleepiness. Because the condition is worse while resting, people with severe RLS may avoid activities that involve extended periods of sitting, such as attending movies or traveling long distances.

Sleep Deprivation

Inability to sleep during the night due to RLS symptoms and subsequent daytime sleepiness can cause mood changes. Lack of sleep can also contribute to workplace errors and car crashes.

Effect on Daily Performance and Activities

Sleeplessness has a negative effect on the ability to function while awake. Areas that can be affected include:

Concentration.

Loss of deep sleep can impair the brain's ability to process information.Task performance.

Missing several hours of sleep every night can negatively affect a person's mood and ability to function. People deprived of sleep show lowered performance levels on a par with those of people who are intoxicated.Learning.

The extent to which sleeplessness impairs learning is unclear. Some studies have reported problems in memorization.

Psychiatric Effects

People with RLS are more likely to suffer problems such as social isolation, frequent daytime headaches, and depression. They may also complain of lower sex drive and other problems related to insufficient sleep.

RLS can contribute to insomnia. Insomnia itself can increase the activity of hormones and pathways in the brain that produce emotional problems. Even modest changes in waking and sleeping patterns can have significant effects on a person's mood. In some cases, ongoing insomnia may even predict mood disorders in the future.

It is not clear if RLS is responsible for mood problems or if anxiety or depression contributes to RLS. Anxiety can cause agitation and leg restlessness that resemble RLS. Depression and RLS symptoms also overlap. Certain types of antidepressant drugs, such as serotonin reuptake inhibitors, can increase periodic limb movements during sleep. Medicines used to treat RLS can cause or increase existing psychiatric conditions. Dopamine agonists, for example, can increase compulsive behaviors, such as gambling.

Some studies have shown patients with RLS have an increased risk of suicide or harming themselves.

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of RLS often relies mainly on the person's description of symptoms. The first step in diagnosis is usually to gather information on a person's sleep and personal history. The doctor may ask the following questions:

- How would you describe your sleep problem?

- How long have you had this sleep problem? How long does it take you to fall asleep?

- How many times a week does the problem occur?

- How restful is your sleep?

- What do your leg problems feel like (such as cramps, twitching, and crawling feelings)?

- What is your sleep environment like? Noisy? Not dark enough?

- What medications are you taking (including the use of antidepressants and self-medications -- such as herbs, alcohol, and over-the-counter or prescription drugs)?

- Are you taking or withdrawing from stimulants, such as coffee or tobacco? How much alcohol do you drink per day?

- What stresses or emotional factors may be present in your life? Have you experienced any significant life changes?

- Do you snore or gasp during sleep? (This may be an indication of sleep apnea. Sleep apnea is a condition in which breathing stops for short periods many times during the night. It may worsen symptoms of RLS or insomnia.)

- If you have a bed partner, does he or she notice that you have jerking legs, interrupted breathing, or thrashing while you sleep?

- Are you a shift worker?

- Do you have a family history of RLS or PLMD, "growing pains" at night, or night walking?

Keeping a Record of Sleep

To help answer some of these questions, the person may need to keep a sleep diary for 2 weeks. The person should record all sleep-related information, including responses to the questions listed above on a daily basis. A bed partner can help provide information based on observations of the person's sleep behavior.

The International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG) have updated and simplified diagnostic criteria for pediatric RLS. The criteria stress the understanding of specific words used by children in describing pain.

Sleep Disorders Centers

Some people may need to consult a sleep specialist or go to a sleep disorders center in order for the problem to be diagnosed. At most centers, people undergo in-depth testing supervised by a team of consultants from various specialties, who can provide both physical and psychiatric evaluations. Centers should be accredited by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine.

Signs that may indicate the need to go to a sleep disorders center are:

- Insomnia due to psychological disorders

- Sleeping problems due to substance abuse

- Snoring and sudden awakening with gasping for breath (possible sleep apnea)

- Severe RLS

- Persistent daytime sleepiness

- Sudden episodes of falling asleep during the day (possible narcolepsy)

Polysomnography

Overnight polysomnography involves a series of tests to measure different functions during sleep. This type of evaluation is typically performed in a sleep center. It can help rule out sleep apnea when this problem is suspected or evaluate the effectiveness of RLS treatments.

To undergo the test, the patient arrives about 2 hours before bedtime without having made any changes in daily habits. This test electronically monitors the person through the various sleep stages. Polysomnography tracks the following:

- Brain waves

- Body movements

- Breathing

- Heart rate

- Eye movements

- Changes in breathing and blood levels of oxygen

There are simpler sleep studies that can be performed in one's own home and may provide information that excludes a sleep disorder or necessitates further confirmation.

Actigraphy

Actigraphy uses a small wristwatch-like device (such as Actiwatch) worn on the wrist or ankle. The device monitors the sleep quality in people suspected of having RLS, PLMD, insomnia, sleep apnea, and other sleep-related conditions. It measures and records muscle movements during sleep. For example, with PLMD, actigraphy can provide information on how long movements last and the number of times they occur. It can also track whether PLMD occurs in both legs at the same time, and the effect it has on sleep. Actigraphy is not as accurate as polysomnography because it cannot measure all the biological effects of sleep. It is more accurate than a sleep log, however, and very helpful for recording long periods of sleep.

Sleepiness Scale

The Epworth Sleepiness Scale uses a simple questionnaire to measure excessive sleepiness during common situations, such as sitting or watching TV.

Diagnosing Iron Deficiency Anemia and Its Causes

Because of the high association between RLS and iron deficiency, a test for low iron stores should be part of the diagnostic workup in RLS. There are two steps in making this diagnosis:

- The first step is to determine if a person is actually deficient in iron.

- If iron stores are low, the second step is to diagnose the cause of the iron deficiency, which will help determine treatment.

The following tests may be used:

Blood smear.

Blood cells viewed under the microscope appear pale (hypochromic) and abnormally small (microcytic). These observations suggest iron deficiency, as well as anemia resulting from chronic disease and thalassemia (an inherited blood disorder).Hemoglobin, iron, ferritin.

Low levels of hemoglobin and iron further suggest iron deficiency, but can also occur in cases of anemia due to chronic disease or other causes. Low levels of ferritin, a protein that binds to iron typically indicate a lack of iron in the body. However, normal levels of ferritin in the blood do not always mean a patient has enough iron. For example, pregnant women in their third trimester or patients with a chronic disease may not have enough iron even with normal or high ferritin levels.STfR.

A test that measures a factor called serum transferrin receptor (sTfR) helps in identifying iron deficiency in some patients, including older people with chronic diseases and possibly pregnant women.- When iron deficiency anemia is diagnosed, the next step is to determine the cause of the iron deficiency itself. Menstrual blood loss is a common cause of iron deficiency in women of reproductive age. Tests to check for an underlying cause of iron deficiency, such as gastrointestinal (digestive tract) bleeding, are particularly important in men, postmenopausal women, and children.

Other Laboratory Tests

The following laboratory tests may be helpful in determining causes of RLS or identifying conditions that rule it out.

- Blood glucose tests for diabetes

- Tests for kidney problems

- In certain cases, tests for thyroid hormone, magnesium, and folate levels

- Electromyography (recording the electrical activity of muscles) for neuropathy or radiculopathy (problem with the nerve roots)

- Central nervous system MRI for myelopathy or stroke

Ruling Out Other Disorders

In addition to other sleep-related leg disorders, many other medical conditions may have features that resemble RLS. The doctor will need to consider these disorders in making a diagnosis.

Peripheral Neuropathies

Peripheral neuropathies are nerve disorders in the hands or feet, which can produce pain, burning, tingling, or shooting sensations in the arms and legs. Several conditions can cause these disorders. Diabetes is a very common cause of painful peripheral neuropathies. Other causes include:

- Alcoholism

- Chemotherapy

- Hereditary neuropathy

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Amyloidosis

- HIV infection

- Kidney failure

- Certain vitamin deficiencies

Symptoms of peripheral neuropathies may mimic RLS. However, unlike RLS, these disorders are not usually associated with restlessness. Also, movement does not relieve the discomfort, and the problem does not worsen at bedtime. While symptoms of neuropathy and RLS can be similar, there is inconsistent evidence that neuropathy may lead to RLS.

Akathisia

Akathisia is a state of restlessness or agitation, and feelings of muscle quivering. A condition called hypotensive akathisia is caused by failure in the autonomic nervous system. Unlike RLS, it occurs at any time of the day, and only when the patient is sitting -- not lying down. Drugs that are used to treat nausea, schizophrenia and other psychoses can cause akathisia. The condition also occurs when drugs to treat Parkinson disease are stopped.

Painful Legs and Moving Toes Syndrome

This is a rare disorder that affects one or both legs. Painful legs and moving toes syndrome is marked by a constant, deep, throbbing ache in the limbs and involuntary toe movements. The discomfort may be mild or severe. The problem gets worse with activity and usually stops during sleep. Most of the time, the cause is unknown, although it may arise from spinal injuries or herpes zoster infection. The condition is difficult to treat, but the drug baclofen, combined with either clonazepam or carbamazepine, has shown some success. Other treatments that may help include orthotic shoe inserts and therapy using transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS).

Meralgia Paresthetica

An uncommon nerve condition, meralgia paresthetica causes numbness, pain, tingling, or burning on the front and side of the thigh. It usually occurs on one side of the body. The condition may be caused by compression of the thigh nerve as it passes through the pelvis. The problem typically occurs in those with diabetes, obesity or both, and can affect people of all ages. It often goes away on its own. Although some features are similar to RLS, this condition is usually easy to distinguish clinically from RLS.

Nocturnal (Nighttime) Leg Cramps

Benign nocturnal leg cramps (Charley horse) are muscle spasms in the calf. They are very common, but they are not RLC or PLMD. Nocturnal leg cramps can be very painful and may cause the person to jump out of bed in the middle of the night. They typically affect a specific area of the calf or the sole of the foot.

Among the conditions that might cause leg cramps are:

- Calcium and phosphorus imbalances, particularly during pregnancy.

- Disorders of the peripheral nerves, such as polyneuropathy due to diabetes, chemotherapy, kidney disease, or others.

- Disorders of the motor neuron, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

- Low potassium or sodium levels.

- Overexertion, standing on hard surfaces for long periods, or prolonged sitting (especially with the legs contorted).

- Having structural disorders in the legs or feet (such as flat feet).

- Medical causes of muscle cramping which include hypothyroidism, Addison's disease, uremia, hypoglycemia, anemia, and certain medications. Various diseases that affect nerves and muscles, such as Parkinson disease, cause leg cramps.

Nighttime leg cramps can generally be treated with lifestyle changes.

Treatment

Treatment for complaints of sleeplessness and RLS focuses on improving sleep and eliminating possible causes of RLS. Initially, doctors normally try to achieve these goals without the use of drugs. A non-drug approach is a particularly important first step for older people.

- The doctor should first try to treat any underlying medical conditions that may be causing restless legs.

- If medications may be causing RLS, the doctor should try to prescribe alternatives, depending on the risk to benefit ratio.

If the cause cannot be determined, measures to improve sleep habits and relaxation techniques are the best first steps. These approaches may help, even if medicines may be needed later on.

Lifestyle Changes

Some people report that making the following changes help control RLS:

- Taking hot baths or using cold compresses.

- Quitting smoking.

- Getting enough exercise during the day.

- Doing calf stretching exercises at bedtime.

- Using ergonomic measures. For example, working at a high stool where legs can dangle helps some people. Also, sitting in an aisle seat during meetings or airplane travel can allow for more leg movement.

- Changing sleep patterns. Some people report that symptoms do not occur when they sleep in the late morning. Therefore, people may consider changing their sleep patterns if feasible.

- Avoiding caffeine, alcohol, and nicotine also improves some cases of RLS.

- Foot wraps have been shown to help some people with RLS in preliminary studies.

Some people have tried alternative treatments for RLS, such as acupuncture and massage. To date, however, there is not enough data on the effectiveness of these treatments.

Dietary Iron

RLS is often associated with iron deficiency, so people with RLS related to iron deficient should make sure they get enough iron in their diet. (For more information, see

In-Depth Report #57

: Anemia.) Iron is found in foods either in the form of heme or non-heme iron:- Foods containing heme iron are the best for increasing or maintaining healthy iron levels. Such foods include clams, oysters, organ meats, beef, pork, poultry, and fish.

- Non-heme iron is less well absorbed. Over half the iron in meat is non-heme. Eggs, dairy products, and iron-containing vegetables (including dried beans and peas) have only the non-heme form. Other sources of non-heme iron include iron-fortified cereals, bread, and pasta products, dark green leafy vegetables (such as chard, spinach, mustard greens, and kale), dried fruits, nuts, and seeds.

Iron Supplements

Iron supplements may reduce symptoms in people with RLS who are also iron deficient. People should use them only when dietary measures have failed. Iron supplements do not appear to be useful for people with RLS with normal or above normal iron levels.

Iron Supplement Forms

To replace iron, the preferred forms of iron tablets are ferrous salts, usually ferrous sulfate (Feosol, Fer-In-Sol, Mol-Iron). Other forms include ferrous fumarate (Femiron, Ferro-Sequels, Feostat, Fumerin, Hemocyte, Ircon), ferrous gluconate (Fergon, Ferralet, Simron), polysaccharide-iron complex (Niferex, Elixir, Nu-Iron), and carbonyl iron (Elemental Iron, Feosol Caplet, Ferra-Cap). Specific brands and forms may have certain advantages.

Iron Supplement Regimen

A reasonable approach for people with RLS who are iron deficient is to take 65 mg of iron (or 325 mg of ferrous sulfate) along with 100 mg of vitamin C on an empty stomach, 3 times a day.

IMPORTANT:

Keep iron supplements out of the reach of children. As few as 3 adult iron tablets can poison, and even kill, children. This includes any form of iron pill. No one should take a double dose of iron if they miss one dose.Tips for taking iron are:

- For best absorption, take iron between meals. (Iron may cause stomach and intestinal disturbances. Some experts believe that you can take low doses of ferrous sulfate with food and avoid the side effects.)

- Always drink a full 8 ounces of fluid with an iron pill.

- Keep tablets in a cool place. Bathroom medicine cabinets may be too warm and humid, which may cause the pills to disintegrate.

Side Effects

Common side effects of iron supplements include the following:

- Constipation and diarrhea may occur but these side effects are rarely severe. However, iron tablets can aggravate existing digestive problems such as ulcers and ulcerative colitis.

- Nausea and vomiting may occur with high doses. You can control this by taking smaller amounts. Switching to ferrous gluconate may help some people with severe digestive problems.

- Black stools are normal when taking iron tablets. In fact, if stools do not turn black, the tablets may not be working effectively.

- Acute iron poisoning is rare in adults, but can be fatal in children who take adult-strength tablets.

Interactions with Other Drugs

Certain medicines, including antacids, can reduce iron absorption.

Iron tablets may also reduce the effectiveness of other drugs, including:

- Antibiotics. Tetracycline, penicillamine, and ciprofloxacin.

- Anti-Parkinson disease drugs. Methyldopa, levodopa, and carbidopa.

At least 2 hours should pass between doses of these drugs and doses of iron supplements. As anti-Parkinson medications may also be used to treat the symptoms of RLS in conjunction with iron, the timing of doses is especially important to consider.

[For additional information about iron supplements see

In-Depth Report #57:

Anemia.]Exercise

Exercise early in the day helps achieve healthy sleep. Vigorous exercise too close to bedtime (1 to 2 hours before) may worsen RLS. A study found that people who walked briskly for 30 minutes, 4 times a week, improved minor sleep disturbances after 4 months. Regular, moderate exercise may help prevent RLS. However, people report that either bursts of excessive energy or long sedentary periods can worsen symptoms.

Medications

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine and the American Academy of Neurology recommend medications for RLS or PLMD only for people who fit within strict diagnostic criteria, and who experience excessive sleep disruption of daytime sleepiness as a result of these conditions. Excessive daytime sleepiness results from disrupted or poor quality sleep due to RLS or PLMD symptoms. Adverse effects are common and may be troublesome enough to prompt some people to discontinue their RLS medications.

More research and physician training is needed to better diagnose and treat RLS with medications in children and adolescents. Little is known about the best way to treat RLS in general, but some experts suggest the following for adults:

- If lifestyle changes do not control the problem, over-the-counter pain relievers should be the first form of treatment.

- People with RLS should have a test for iron deficiency. If they are iron deficient, they should start treatment with iron supplements.

- Dopaminergic drugs (drugs that increase levels of dopamine) and gabapentin enacarbil are the standard medicines for treating severe RLS, PLMD, or both.

- Other drugs may be helpful if dopaminergic drugs fail, or for people who have frequent, but not nightly, symptoms. These include opiates (pain relievers), benzodiazepines (sedative hypnotic drugs), or anticonvulsants. However, benzodiazepines and opiates can easily become habit forming and addictive and should be used as a last option.

- Each of these treatments must be tailored to a person's specific situation such as concurrent psychiatric symptoms and concern for augmentation. Co-existing kidney disease may also require adjustment of medications that are affected by kidney function.

Tylenol and Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

Before taking stronger medications, people should try over-the-counter pain relievers, such as acetaminophen (Tylenol) or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which include ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin, Rufen), naproxen (Anaprox, Naprosyn, Aleve), and ketoprofen (Orudis KT, Actron).

Although NSAIDs work well, long-term use can cause stomach problems, such as ulcers, bleeding, and possible heart problems. The FDA has asked drug manufacturers of NSAIDs to include a warning label on their product that alerts users of an increased risk for heart-related problems and digestive tract bleeding.

Levodopa and Other Dopaminergic Drugs

Dopaminergic drugs increase the availability of the chemical messenger dopamine in the brain and are one of the first-line treatments for severe RLS and PLMD. These drugs reduce the number of limb movements per hour and improve the subjective quality of sleep. People with either condition who take these drugs have experienced up to 100% initial reduction in symptoms.

Dopaminergic drugs, however, can have severe side effects (they are ordinarily used for Parkinson disease). They do not appear to be as helpful for RLS related to dialysis as they do for RLS from other causes.

Dopaminergic drugs include dopamine precursors and dopamine receptor agonists.

Dopamine Precursors

The dopamine precursor levodopa (L-dopa) was once a popular drug for severe RLS, although today it is usually recommended only for patients with occasional symptoms who may take it nightly as needed. It may also be helpful for long car rides or plane trips. The standard preparations (Sinemet, Atamet, Parcopa, Rytary) combine levodopa with carbidopa, which improves the action and duration of levodopa and reduces some of its side effects, particularly nausea. Levodopa combinations are well tolerated and safe.

Levodopa acts fast, and the treatment is usually effective within the first few days of therapy.

Unfortunately, many studies report that up to 70% of people with RLS who take levodopa suffer from reduced response to treatment over time (called tolerance) or worsening of symptoms despite treatment (called augmentation). Augmentation can also cause symptoms to occur earlier in the day. The risk is highest for people who take daily doses, especially doses at high levels (greater than 200 mg/day). For this reason, people should use L-dopa fewer than 3 times per week. The drug should be immediately discontinued if augmentation does occur. Following withdrawal from L-dopa, people can switch to a dopamine receptor agonist.

A rebound effect (return of symptoms after the drug is discontinued) causes increased leg movements at night or in the morning as the dose wears off, or as tolerance to the drug builds up.

Regimens

The effects of L-dopa are apparent in 15 to 30 minutes. Dopamine receptor agonists, meanwhile, take at least 2 hours to start working. Some doctors recommend regular use of dopamine receptor agonists for people who experience nightly symptoms and L-dopa for those whose symptoms occur only occasionally.

Side Effects

Common side effects of dopaminergic drugs vary but may include feeling faint or dizzy (especially when standing up), headaches, abnormal muscle movements, rapid heartbeat, insomnia, bloating, chest pain, and dry mouth. Nausea may be especially common. In rare cases, dopaminergic drugs can cause hallucinations or lung disease. Long-term treatment with levodopa can also lead to drug-induced dyskinesia, a condition characterized by exaggerated involuntary movements or uncontrolled muscle contractions.

Because these drugs may cause daytime drowsiness, people should be extremely careful while driving or performing tasks that require concentration.

Long-term use of dopaminergic drugs can lead to tolerance, in which the drugs become less effective.

Rebound effect, augmentation, and tolerance can reduce the value of dopaminergic drugs in the treatment of RLS. Using the lowest dose possible can minimize these effects.

Withdrawal Symptoms

Patients who withdraw from these drugs typically experience severe RLS symptoms for the first 2 days after stopping. RLS eventually returns to pre-treatment levels after about a week. The longer a patient uses these drugs, the worse their withdrawal symptoms.

Withdrawal from dopamine precursors or dopamine agonists can lead to a serious, potentially life-threatening condition called Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome. This disorder causes muscle stiffness and breakdown, fever, rigidity, and confusion. One should never abruptly stop these medications without first talking to their doctor.

Dopamine Receptor Agonists

Dopamine receptor agonists (also called dopamine agonists) mimic the effects of dopamine by acting on dopamine receptors in the brain. They are now generally preferred to L-dopa (see below). Because they have fewer side effects than L-dopa, these drugs may be used on a daily basis. As the newer drugs are taken for longer periods and at higher doses, however, their augmentation rates may become closer to those of L-dopa.

Because they take longer to take effect, these drugs are not as useful to relieve symptoms once they have begun.

Dopamine agonists have been shown to relieve symptoms in 70% or more of people.

- Ropinirole (Requip) was the first drug approved specifically for treatment of moderate-to-severe RLS (more than 15 RLS episodes a month). Side effects are generally mild but may include nausea, vomiting, drowsiness, and dizziness. A small percentage of people may experience their symptoms worsening and rebound symptoms when the medicine wears off.

- Pramipexole (Mirapex) is also approved for RLS. However, people may fall asleep, without warning, while taking this drug, even while performing activities such as driving.

- Rotigotine (Neupro) is a patch preparation. Common side effects include back or joint pain, dizziness, decreased appetite, dry mouth, fatigue, sweating, trouble sleeping, or upset stomach.

- Cabergoline and pergolide are dopamine agonists that should be used only when other medications have been tried and failed they pose a risk of

heart valve damage

.

Other Dopamine Agonists

Other dopamine agonists that have been tested in small studies include alpha-dihydroergocryptine, or DHEC (Almirid), and piribedil (Trivastal). However, there is not enough evidence to support their use for RLS treatment and they are not approved by the FDA.

Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines, such as clonazepam (Klonopin), are known as sedative hypnotics. Doctors prescribe them for insomnia and anxiety. They may be helpful for RLS that disrupts sleep, especially in younger people. Clonazepam may be particularly helpful for children with both PLMD and symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. The medicine also may be helpful for people with RLS who are undergoing dialysis. There is insufficient evidence that this class of medications is effective in treating RLS.

Side Effects

Older people are more susceptible to side effects. They should usually start at half the dose prescribed for younger people, and should not take long-acting forms. Side effects may differ depending on whether the benzodiazepine is long-acting or short-acting.

- The drugs may increase depression, a common condition in many people with insomnia.

- Breathing problems may occur with overuse or in people with a pre-existing respiratory illness.

- Long-acting drugs have a very high rate of residual daytime drowsiness compared to others. They have been associated with a significantly increased risk for automobile accidents and falls in the elderly, particularly in the first week after taking them. Shorter-acting benzodiazepines do not appear to pose as high a risk.

- There are reports of memory loss (so-called traveler's amnesia), sleepwalking, and odd mood states after taking triazolam (Halcion) and other short-acting benzodiazepines. These effects are rare and probably enhanced by alcohol.

- Because benzodiazepines can cross the placenta and enter breast milk, pregnant and nursing women should not use them. There are some reports of an association between the use of benzodiazepines in the first trimester of pregnancy and the development of cleft lip in newborns. Studies are conflicting at this point, but other side effects are known to occur in babies exposed to these drugs in the uterus.

- In rare cases, overdoses have been fatal.

Interactions

Benzodiazepines are potentially dangerous when used in combination with alcohol. Some drugs, such as the ulcer medication cimetidine, can slow the breakdown of benzodiazepine.

Withdrawal Symptoms

Withdrawal symptoms usually occur after prolonged use and indicate dependence. They can last 1 to 3 weeks after stopping the drug and may include:

- Gastrointestinal distress.

- Sweating.

- Disturbed heart rhythm.

- In severe cases, people might hallucinate or experience seizures, even a week or more after they stop taking the drug.

Rebound Insomnia

Rebound insomnia, which often occurs after withdrawal, typically includes 1 to 2 nights of sleep disturbance, daytime sleepiness, and anxiety. The chances of rebound are higher with the short-acting benzodiazepines than with the longer-acting ones.

Narcotic Pain Relievers

Narcotics are pain-relieving drugs that act on the central nervous system. They are sometimes prescribed for severe cases of RLS. They may be a good choice if pain is a prominent feature, but chronic narcotic administration should be done carefully due to a high risk of abuse and dependence.

There are two types of narcotics, both of which have been used for severe RLS:

Opiates

(such as morphine and codeine) come from natural opium.Opioids

are synthetic drugs. Common examples include oxycodone (Percodan, Percocet, Roxicodone, OxyContin), methadone (Dolophine), and hydrocodone (Vicodin), fentanyl (Duragesic), and tramadol (Ultram).

The use of such drugs may be beneficial when included as part of a comprehensive pain management program. Such a program involves screening prospective patients for possible drug abuse and regularly monitoring those who are taking narcotics. Doses should be adjusted as necessary to achieve an acceptable balance between pain relief and side effects. People on long-term opiate therapy should also be monitored periodically for sleep apnea, a condition that causes breathing to stop for short periods many times during the night. Sleep apnea may worsen symptoms of RLS, insomnia, and other complaints.

Antiseizure Drugs

Antiseizure drugs, such as gabapentin (Neurontin), valproic acid (valproate, divalproex, Depakote, Depakene), and carbamazepine (Tegretol) are being tested for RLS. Common side effects included mild sleepiness and dizziness.

Gabapentin enacarbil (Horizant) is an extended-release prodrug form of gabapentin that is one of the few drugs approved by the FDA specifically for the treatment of moderate to severe RLS.

Side Effects

All antiseizure drugs have potentially severe side effects. Therefore, people should try these medications only after non-drug methods have failed. Side effects of many anti-seizure drugs include nausea, vomiting, heartburn, increased appetite with weight gain, hand tremors, irritability, and temporary hair thinning and hair loss. Taking zinc and selenium supplements may help reduce this last effect. Some anti-seizure drugs can also cause birth defects and, in rare cases, liver toxicity. Gabapentin may have fewer of these side effects than valproic acid or carbamazepine. Recently, there has been concern that gabapentin may also be prone to abuse, especially when used in conjunction with opiates.

Other Drugs

Antidepressants

Bupropion (Wellbutrin), a newer antidepressant, may be helpful for RLS, at least in the short-term. Bupropion is a weak dopamine reuptake inhibitor, it causes a slight increase in the availability of dopamine in the brain. The drug is not addictive and does not have the severe side effects of other RLS drugs, but more research is needed to determine if it is useful.

Clonidine

Clonidine (Catapres), a drug used for high blood pressure, is helpful for some people and may be an appropriate choice for people who have RLS accompanied by hypertension. It also may help people with RLS who are undergoing hemodialysis.

Baclofen

The anti-spasm drug baclofen (Lioresal) appears to reduce intensity of RLS (although not frequency of movements).

Pregabalin

Pregabalin (Lyrica) is approved for the treatment of diabetic neuropathy, postherpetic neuralgia, and fibromyalgia, and may also be helpful in the treatment of RLS.

Non-pharmacologic Therapy

The FDA has approved the use of several vibratory counter-stimulation devices for the treatment of primary RLS. These electrical devices are either placed under the legs or worn by the patient during sleep and work by delivering vibrations through the skin that are supposed to improve the quality of sleep. Better studies are needed on the effectiveness of these devices for RLS.

Other Treatments

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is being studied to see if it is safe and effective for RLS. DBS requires surgery to place wire electrodes into the brain and a small battery under the skin in the chest. Because this requires brain surgery, it is only used after many other treatments have failed.

Cannabis has also been shown to help some people. Local laws may prevent some people from access.

Resources

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine -- aasm.org

- National Sleep Foundation -- www.thensf.org/

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke -- www.ninds.nih.gov

- National Center on Sleep Disorders Research -- www.nhlbi.nih.gov/about/scientific-divisions/national-center-sleep-disorders-research

- Restless Legs Syndrome Foundation -- www.rls.org/

References

Allen RP, Montplaisir J, Walters AS, Ferini-Strambi L, Hogl B. Restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movements during sleep. In: Kryger M, Roth T, Dement WC, eds. Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017:chap 95.

Aurora RN, Kristo DA, Bista SR, et al. Update to the AASM clinical practice guideline: The treatment of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder in adults--an update for 2012: practice parameters with an evidence-based systematic review and meta-analyses. Sleep. 2012;35(8):1039-1062. PMID: 22851801 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22851801/.

Balserak BI, Lee KA. Sleep and sleep disorders associated with pregnancy. In: Kryger M, Roth T, Dement WC, eds. Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017:chap 156.

Bertisch S. In the clinic. Restless legs syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(9):ITC1-ITC11. PMID: 26524584 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26524584/.

Casoni F, Galbiati TF, Ferini-Strambi L, Marelli S, Zucconi M, Servello D. DBS in restless legs syndrome: a new therapeutic approach? Sleep Med. 2020;76:155-157. PMID: 33217666 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33217666/.

Chokroverty S, Avidan AY. Sleep and its disorders. In: Daroff RB, Jankovic J, Mazziotta JC, et al, eds. Bradley's Neurology in Clinical Practice. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:chap 102

Durmer JS. Restless legs syndrome, periodic leg movements and periodic limb movement disorder. In: Sheldon SH, Ferber R, Kryger MH, Gozal D, eds. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Sleep Medicine. 2nd ed. Elsevier Saunders; 2014:chap 43.

Garcia-Borreguero D, Silber MH, Winkelman JW, et al. Guidelines for the first-line treatment of restless legs syndrome/Willis-Ekbom disease, prevention and treatment of dopaminergic augmentation: a combined task force of the IRLSSG, EURLSSG, and the RLS-foundation. Sleep Med. 2016;21:1-11. PMID: 27448465 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27448465/.

Gopaluni S, Sherif M, Ahmadouk NA. Interventions for chronic kidney disease-associated restless legs syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11:CD010690. PMID: 27819409 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27819409/.

Huang CW, Lee MJ, Wang LJ, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of treatments for restless legs syndrome in end-stage renal disease: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35(9):1609-1618. PMID: 31157898 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31157898/.

Jahani Kondori M, Kolla BP, Moore KM, Mansukhani MP. Management of Restless Legs Syndrome in Pregnancy and Lactation. J Prim Care Community Health. 2020;11:2150132720905950. PMID: 32054396 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32054396/.

Jiménez-Jiménez FJ, Alonso-Navarro H, García-Martín E, Agúndez JAG. Genetics of restless legs syndrome: An update. Sleep Med Rev. 2018;39:108-121. PMID: 29033051 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29033051/.

Kalra S, Gupta A. Diabetic Painful Neuropathy and Restless Legs Syndrome in Diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2018;9(2):441-447. PMID: 29427229 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29427229/.

Kolla BP, Mansukhani MP, Bostwick JM. The influence of antidepressants on restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movements: A systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2018;38:131-140. PMID: 28822709 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28822709/.

Mackie SE, Winkelman JW. Therapeutic utility of opioids for restless legs syndrome. Drugs. 2017;77(12):1337-1344. PMID: 28616844 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28616844/.

de Oliveira CO, Carvalho LB, Carlos K, et al. Opioids for restless legs syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(6):CD006941. PMID: 27355187 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27355187/.

Owens JA. Sleep medicine. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 31.

Picchietti DL, Bruni O, de Weerd A, et al, International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG). Pediatric restless legs syndrome diagnostic criteria: an update by the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group. Sleep Med. 2013;14(12):1253-1259. PMID: 24184054 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24184054/.

Ramar K, Olson EJ. Management of common sleep disorders. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88(4):231-238. PMID: 23944726 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23944726/.

Silber MH, Becker PM, Earley C, et al. Willis-Ekbom Disease Foundation Revised Consensus Statement on the Management of Restless Legs Syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(9):977-986. PMID: 24001490 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24001490/.

Suraev AS, Marshall NS, Vandrey R, McCartney D, Benson MJ, McGregor IS, Grunstein RR, Hoyos CM. Cannabinoid therapies in the management of sleep disorders: A systematic review of preclinical and clinical studies. Sleep Med Rev. 2020 Oct;53:101339. PMID: 32603954 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32603954/.

Vaughn BV, Basner RC. Sleep disorders. In: Goldman L, Schafer AI, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 26th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2020:chap 377.

Wijemanne S, Ondo W. Restless Legs Syndrome: clinical features, diagnosis and a practical approach to management. Pract Neurol. 2017;17(6):444-452. PMID: 29097554 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29097554/.

Winkelman JW, Armstrong MJ, Allen RP, et al. Practice guideline summary: treatment of restless legs syndrome in adults: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2016;87(24):2585-2593. PMID: 27856776 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27856776/.

Zhuang S, Na M, Winkelman JW, Ba D, Liu CF, Liu G, Gao X. Association of Restless Legs Syndrome With Risk of Suicide and Self-harm. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(8):e199966. PMID: 31441941 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31441941/.

|

Review Date:

12/15/2020 Reviewed By: Joseph V. Campellone, MD, Department of Neurology, Cooper Medical School at Rowan University, Camden, NJ. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team. |

© 1997- A.D.A.M., a business unit of Ebix, Inc. Any duplication or distribution of the information contained herein is strictly prohibited.