Gout - InDepth

Highlights

Introduction

- Gout is a painful inflammatory arthritis condition caused by deposits of uric acid crystals in the joints and soft tissues. The painful attacks often begin at night and may last for a week.

- 8.3 million people in the United States have gout. This number is growing because of an aging population, the rise in obesity, increasing numbers of people who also have other conditions such as heart disease, kidney disease, and/or diabetes. The use of diuretics by people with cardiovascular disease is another cause of the increase in gout prevalence.

Treatment and Management

- Some medications are aimed at treating acute attacks by reducing pain and inflammation in the joints and other tissues.

- Other medications are aimed at preventing future attacks by lowering uric acid in the body.

- These medications are generally well tolerated and may include allopurinol, febuxostat, and probenecid.

- When medications to lower uric acid levels are first started, flare-ups of gout are more likely. Thus, it is important to take medications to prevent flare-ups during this time.

- Lifestyle changes are important in preventing attacks and managing the condition. Measures include losing weight, limiting foods and beverages with a high purine content, and limiting alcohol.

Introduction

Gout is a metabolic disorder that causes a painful and common type of arthritis. It is caused when there is too much uric acid in the blood. This is called hyperuricemia. Uric acid is a breakdown product of normal metabolism in the body and is normally excreted through urine. Buildup of uric acid results in needlelike crystals forming in the joints, soft tissues, and organs.

Cases of gout have increased in recent years. This increase is likely due to an aging population, dietary and lifestyle changes, the rising incidence of obesity, greater use of medicines, such as diuretics (water pills), all of which can lead to a high uric acid level in the body.

How Hyperuricemia and Gout Develop

Metabolism of Purines

The process leading to hyperuricemia and gout begins with the metabolism, or breakdown, of purines. Purines are compounds that are important for energy. They are part of the nucleic acids (DNA and RNA) that are present in all cells of the body. Purines can be divided into two types:

- Endogenous purines are produced within human cells.

- Exogenous purines are obtained from food.

The process of breaking down purines results in the formation of uric acid in the body. Most mammals, except humans, have an enzyme called uricase. Uricase breaks down uric acid so it can be easily removed from the body. Because humans lack uricase, uric acid is not easily removed and can build up in body tissues.

Uric Acid and Hyperuricemia

Purines in the liver are converted to uric acid. The uric acid enters the bloodstream. Most of the uric acid goes through the kidneys and is excreted in urine. The remaining uric acid travels through the intestines where bacteria help break it down.

The enzyme responsible for production of uric acid from purines is xanthine oxidase. This enzyme is the target of urate-lowering treatments such as allopurinol.

Normally these processes keep the level of uric acid in the blood below 6.8 mg/dL. But sometimes the body produces too much uric acid or removes too little. In either case, the level of uric acid increases in the blood. This condition is known as hyperuricemia.

If uric acid reaches a level in the blood of 6.2 -6.8 mg/dL or higher, it becomes insoluble and needlelike crystals of a salt called monosodium urate (MSU) may form. In lower temperature areas of the body (such as the joints in the feet) crystals can form at lower concentrations.

As crystals build up in the joints, they may trigger inflammation, redness, swelling, and pain. These are the symptoms of gout. However, most people with hyperuricemia do not have symptoms of gout. The higher the level of uric acid, the higher the risk for crystal formation. Approximately 0.5% of people with a uric acid level between 7.0 to 8.9 mg/dL develop gout and around 5% of people with a uric acid greater than 9 mg/dL have gout.

Symptoms

Symptoms of gout depend on the stage of the disease. Gout can be divided into four stages:

- Asymptomatic hyperuricemia

- Acute gouty arthritis

- Intercritical gout

- Chronic tophaceous gout

Asymptomatic Hyperuricemia

Asymptomatic means there are no symptoms. Increase in blood uric acid (hyperuricemia) is the first stage of gout. This stage may last 30 years or more.

Note:

Hyperuricemia does not always lead to gout. Less than 20% of people with hyperuricemia develop gout. However, there is an association between hyperuricemia and the risk for hypertension, heart disease, and kidney disease. This association is being studied carefully since it might be possible to lower uric acid and reduce the risk of developing these diseases. At the moment, however, treating asymptomatic hyperuricemia is not recommended.Symptoms of Acute Gouty Arthritis

Acute gouty arthritis occurs when the first symptoms of gout appear. Sometimes the first signs of gout are brief twinges of pain (petit attacks) in an affected joint. These attacks can occur for several years before the full-blown condition occurs.

Symptoms of acute gouty arthritis often start in one joint and include any of the following:

- Severe pain at and around the joint: may feel like "crushing" or a dislocated bone; physical activity and even the weight of bed sheets may be unbearable; usually takes 8 to 12 hours to develop; occurs late at night or early in the morning and may wake you up.

- Swelling that may extend beyond the joint.

- Warmth over the joint.

- Red, shiny, tense skin over the affected area, which may peel after a few days.

- Chills and mild fever, loss of appetite, not feeling well in general.

Monoarticular Gout

Gout that occurs in one joint is called monoarticular gout. About 60% of all first-time monoarticular gout attacks in middle-aged adults occur in the big toe. This is known as podagra. Symptoms can also occur in other locations such as the ankle or knee.

Polyarticular Gout

If more than one joint is affected, the condition is known as

polyarticular gout

. Multiple joints are affected in only 10% to 20% of first attacks. Older people are more likely to have polyarticular gout. The most frequently affected joints are the foot, ankle, knee, wrist, elbow, and hand. The pain usually occurs in joints on one side of the body and it is usually, though not always, in the lower legs and the feet. People with polyarticular gout are more likely to have a slower onset of pain and a longer delay between attacks. People with polyarticular gout are also more likely to experience low-grade fever, loss of appetite, and a general feeling of poor health.An untreated attack peaks 24 to 48 hours after symptoms first appear and goes away after 5 to 7 days. Some attacks last only hours, while others go on for as long as several weeks. Though symptoms can subside, the crystals are still present and future attacks are likely to occur.

Intercritical Gout

Intercritical gout is the term used to describe the periods between attacks. The first attack is usually followed by a complete disappearance (remission) of symptoms. But, untreated, gout nearly always returns. Over two-thirds of patients have at least one more attack within 2 years of the first attack. By 10 years, over 90% of patients who had one attack are likely to have more attacks.

Symptoms of Chronic Tophaceous Gout

Chronic Tophaceous Gout and Tophi

After several years, patients with elevated uric acid can develop deposits of uric acid called tophi. These are solid deposits of uric acid crystals that form in the joints, cartilage, bones, and elsewhere in the body. In some cases, tophi break through the skin and appear as white or yellowish-white, chalky nodules that have been described as looking like crab eyes.

Without treatment to lower the uric acid, tophi develop about 10 years after the onset of gout, although tophi can occur from 3 to 42 years after gout starts. Tophi are more likely to appear early in the course of the disease in older people. In older people, women are at higher risk of developing tophi than men. People who have had an organ transplant and are on the medicine cyclosporine also have a high risk of developing tophi.

Chronic Pain

When gout remains untreated, the periods between attacks of acute gout become shorter and shorter and the attacks, although sometimes less intense, can last longer. In about 10 to 20 years gout becomes a chronic disorder with constant low-grade pain and mild or acute inflammation. Gout may later affect several joints, including those that may have been free of symptoms at the start of the disorder. In rare cases, the shoulders, hips, or spine are affected.

Location of Tophi

Tophi may form in the following locations:

- Curved ridge along the edge of the outer ear

- Forearms

- Elbow or knee

- Hands or feet. Older patients, particularly women, are more likely to have gout in the small joints of the fingers.

- Around the heart and spine (rare)

Tophi are usually painless. But they can cause pain and stiffness in the affected joint. In time, they can also damage cartilage and bone and destroy the joint. Large tophi under the skin of the hands and feet can cause severe deformities.

Complications

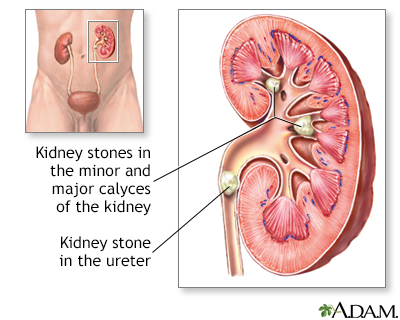

Uric Acid Nephrolithiasis (Kidney Stones)

People who have kidney stones that formed from uric acid are more likely to have hyperuricemia which suggests hyperuricemia is responsible for this type of kidney stone. Uric acid stones can also form in a person who does not have gout or hyperuricemia.

Not all kidney stones in patients with gout are made of uric acid. Some are made of calcium oxalate, calcium phosphate, or substances combined with uric acid. Uric acid stones can also form in a person who does not have gout or hyperuricemia.

Chronic Uric Acid Interstitial Nephropathy

Chronic uric acid interstitial nephropathy occurs when crystals slowly form in the structures and tubes that carry fluid from the kidney. This condition can sometimes injure the kidneys.

Chronic Kidney Disease

Gout and chronic kidney disease appear to be closely associated. Gout is more likely to occur as kidney function worsens. For many years, hyperuricemia was not thought to cause kidney disease. The question is now under careful review (see Asymptomatic Hyperuricemia).

Acute Kidney Failure

Sudden overproduction of uric acid can sometimes block the kidneys and cause them to fail. This occurrence is very rare but can develop after any of the following:

- Chemotherapy for leukemia or lymphoma, particularly acute forms of the disease

- Other cancers, such as breast cancer and lung cancer

- Epileptic seizures

- Preeclampsia or eclampsia

- Use of medications to prevent kidney transplant rejection, such as cyclosporine

Causes and Risk Factors

Gout is considered either primary or secondary, depending on the causes of the high uric acid level in the blood (hyperuricemia).

Nearly all cases of primary gout cases are idiopathic. This means that the cause of the hyperuricemia cannot be determined. Primary gout is most likely the result of a combination of genetic, hormonal, and dietary factors. Secondary gout is caused by medicines or by medical conditions other than a metabolic disorder.

The following factors increase the risk of developing gout:

- Age

- Male gender

- Family history of the condition; genetic predisposition

- Obesity or weight gain

- Medicines, including diuretics (water pills), low-dose aspirin, cyclosporine, or levodopa

- Alcohol consumption, including binge drinking

- Diet rich in red meat, seafood, sweets, and sweet fruits or fruit juices

- Lead toxicity

- Organ transplant

- Thyroid problem

- Other serious illness

People with gout are at an increased risk of having metabolic syndrome. Metabolic syndrome is a collection of health problems, such as abdominal obesity, high blood pressure, and low (good) cholesterol. This syndrome increases a person's risk for heart disease and stroke. Therefore, lifestyle changes are an important aspect of preventing gout and improving overall health.

Each risk factor is discussed below.

Age

Middle-Aged Adults

Gout usually occurs in men in the mid-40s. Men of this age group who have gout are often obese, have high blood pressure, unhealthy cholesterol levels, and drink large amounts of alcohol.

Older adults

In the older age group, the risk of developing gout is equal in men and women. In this group, gout is most often associated with kidney problems and the use of diuretics. It is less often associated with alcohol use.

Children

Gout in children is uncommon except for rare inherited genetic disorders that cause hyperuricemia.

Gender

Men

Men are at much higher risk of developing gout than women. In men, uric acid level normally rises at puberty. In some American men, the level is higher than normal, which means they have hyperuricemia. Gout symptoms appear after 20 to 40 years of persistent hyperuricemia. Men who develop gout usually experience their first attack between the ages of 30 and 50.

Women

Before menopause, women have a much lower risk of developing gout than men. This may be because estrogen causes more uric acid to be excreted by the kidneys. Only about 15% of gout cases in women occur before menopause. After menopause the risk increases. At age 60, the risk of developing gout in men and women is equal. After age 80, gout occurs more often in women.

Family History and Genetics

About 20% of people with gout have family histories of this condition. Several genes are linked to uric acid metabolism and gout. Some people have a defective protein (enzyme) that interferes with the way the body breaks down purines.

Obesity

Scientists have found a clear link between body weight and uric acid level. The higher a person's body mass index (BMI), the higher the chance of developing gout. As a result, the risk of developing gout in many countries is rising because of the rising incidence of obesity. Children who are obese may have an increased risk of developing gout as adults.

Medications

Thiazide diuretic medicines, or water pills, are used to control high blood pressure (hypertension). These medicines are strongly linked to the development of gout. Many older patients who develop gout take diuretics.

Other medicines can also increase uric acid level and raise the risk of developing gout. These include:

- Aspirin. Low doses reduce uric acid excretion and increase the chance of hyperuricemia. This may be a problem for older people who take low-dose aspirin to protect against heart disease.

- Niacin (used to treat cholesterol problems).

- Pyrazinamide (used to treat tuberculosis).

- Cyclosporine and tacrolimus, two drugs used to manage the body's immune response.

- Levodopa, commonly used to treat Parkinson disease.

- Beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors, other drugs used to treat high blood pressure.

Alcohol

Drinking excessive amounts of alcohol can raise the risk of developing gout. Beer is most strongly linked to gout, followed by spirits. Moderate wine intake does not seem to increase the risk of developing gout.

Alcohol use is highly associated with gout in younger adults. Binge drinking particularly increases uric acid level. Alcohol appears to play less of a role among older patients, especially among women with gout.

Alcohol increases uric acid level in the following three ways:

- Provides an additional dietary source of purines (the compounds from which uric acid is formed)

- Intensifies the body's production of uric acid

- Lowers the kidneys' ability to excrete uric acid

Lead Exposure

Long-term exposure to lead is associated with buildup of uric acid and a high incidence of gout. Some "moonshine" alcohol has elevated lead levels.

Organ Transplants

People who have had a kidney transplant have a high risk of developing gout. Other organ transplants, such as heart and liver, also increase the risk of developing gout. This is because the surgery itself raises the risk of developing gout, as does the medicine cyclosporine used to prevent rejection of the transplanted organ. Cyclosporine also interacts with indomethacin, a common gout medicine.

The kidneys are responsible for removing waste from the body, regulating electrolyte balance and blood pressure, and stimulating red blood cell production.

Other Illnesses

Treatment of other conditions can lead to a high level of uric acid in the blood, resulting in a gout attack. These conditions include:

- Leukemia

- Lymphoma

- Psoriasis

Triggers

Triggers are events or conditions that can set off a gout attack. Triggers include:

- Joint injury

- Too much alcohol or purine-rich foods

- Dehydration

- Severe illness or infection

- Sudden weight loss, crash dieting

- Surgery

- Radiation therapy

- Using certain drugs

Diagnosis

The first step in diagnosing gout is to determine which joints are affected. A physical examination and medical history can help confirm or rule out gout. For example, gout is more likely if arthritis first appears in the big toe.

The speed of the onset of pain and swelling is also important. Symptoms that take days or weeks (rather than hours) to develop probably point to a problem other than gout.

Unusual enlargements in joints that had been affected by previous injury or osteoarthritis are possible signs of gout. This is especially true in older women who take diuretics (water pills).

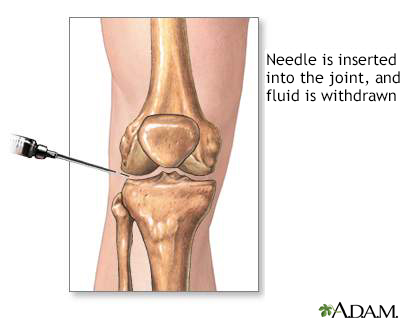

Examination of Synovial Fluid

Synovial fluid examination is the most accurate method for diagnosing gout. The synovial fluid is the lubricating liquid that fills the joint space (synovium). This is the membrane that surrounds a joint and creates a protective sac. The fluid cushions joints and supplies nutrients and oxygen to the cartilage surface that coats the bones. This exam also helps detect gout between attacks.

A procedure called arthrocentesis is performed. The health care provider uses a needle attached to a syringe to draw out fluid from the affected joint. This is called aspiration. The fluid sample is sent to a laboratory. If crystals of uric acid, also called monosodium urate (MSU) are found, this makes the diagnosis of gout. These crystals are very distinctive under the microscope using special polarizing filters. Aspiration sometimes eases symptoms by reducing swelling and pressure on the tissue surrounding the joint.

Synovial fluid analysis is a method to look at the fluid that cushions a joint. It is done to help diagnose and treat joint-related problems such as gout.

Blood Test for Uric Acid Level

A blood test may be done to measure uric acid level in the blood. Since uric acid can fall during an attack, the uric acid may not be elevated at that time. Some doctors may wait until several days after the attack to order a blood test. Nearly all people with gout have elevated uric acid in this case, although not all people with elevated uric acid have gout. Therefore the blood uric acid is only one part of making the diagnosis.

Urine Test

Sometimes a urine test is done to check the amount of uric acid in a patient's urine. If uric acid in the urine is higher than a certain value, further tests for an enzyme defect or other cause of gout will be ordered. A high level of uric acid in the urine means that the patient is more likely to develop uric acid kidney stones. Some available medications increase uric acid excretion and may alter this test result.

Imaging Tests

X-Rays

X-rays do not usually show problems during the early stages of gout. X-rays are more often used in chronic gout. X-rays may help find other problems with symptoms similar to gout. Tophi can be seen on x-rays before they can be found during a physical exam.

Advanced Imaging Techniques

In very rare cases, advanced imaging techniques are used for identifying tophi. These techniques include computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and Doppler ultrasonography.

Ruling Out Other Disorders

As part of the diagnosis, other disorders that cause gout-like symptoms or cause hyperuricemia should be ruled out. In general, it is easy to distinguish acute gout that occurs in one joint from other arthritic conditions. The two disorders that may confuse this diagnosis are pseudogout and septic arthritis. Pseudogout is a condition most likely to be confused with gout.

Chronic gout can often resemble rheumatoid arthritis. Other conditions may at some point in their course resemble gout.

Pseudogout (Calcic Gout)

Pseudogout is also called calcic gout or calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition disease. It is a common inflammatory arthritis in older adults. It is similar to gout. Like gout, pseudogout is caused by deposits of crystals in and around the joints. But the type of crystals of pseudogout is calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate (CPPD). These are quite different under the microscope compared to uric acid crystals.

Symptoms of pseudogout resemble gout in some ways, but there are differences:

- The first attack usually affects the knee. Other joints commonly affected are the shoulders, wrists, and ankles. At least two-thirds of cases affect more than one joint during a first attack. Pseudogout may involve any joint, although the small joints in the fingers or toes are not commonly affected.

- The symptoms of pseudogout also appear more slowly than those of gout, taking days, rather than hours, to develop.

- Pseudogout is more likely to first develop in older people, particularly those with osteoarthritis.

Who Gets Pseudogout?

Conditions that have a high risk for pseudogout in older patients include acute medical conditions, trauma, or surgery. Medical conditions linked to pseudogout include hypothyroidism, diabetes, gout, and osteoarthritis. Liver transplantation may also increase the risk. X-rays often show calcium deposits in the joint cartilage. This is not seen in uric acid gout.

How is Pseudogout Treated?

There is no cure for removing the calcium deposits that cause pseudogout. It is a progressive disorder that can eventually destroy joints. Treatments for acute attacks of pseudogout are similar to those for gout and are aimed at relieving the pain and inflammation and reducing the frequency of attacks.

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are effective for treating inflammation and pain from pseudogout.

- For acute attacks in large joints, fluid aspiration alone or with corticosteroids may help.

- Colchicine may be used for acute attacks.

- Magnesium carbonate may help dissolve crystals, but existing hard deposits may remain.

- Surgery may be required for joint replacement.

Other Disorders

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis can cause deformations of the joints of the fingers and cause inflammation and pain that may be similar to gout. In older people, it is hard to tell chronic gout from rheumatoid arthritis. A proper diagnosis can be made with a detailed medical history, laboratory tests, and identification of MSU crystals.

Osteoarthritis

Gout can coincide and be confused with osteoarthritis in older people, particularly when it occurs in arthritic finger joints in women. In general, gout should be suspected if the joints in the fingertips are unusually enlarged.

Infections

Joint infections can have features that resemble gout. A correct diagnosis is important for proper treatment. A high fever and high white blood cell count help diagnose infection, while urate crystals in the joint usually point to gout.

Charcot Foot

People with diabetes who also have problems in the nerves in the feet (diabetic peripheral neuropathy) may develop Charcot foot or Charcot joint (medically known as neuropathic arthropathy). Early changes may resemble gout, with the foot becoming swollen, red, and warm, although it involves other parts of the foot other than the large toe.

Bunions

A bunion is a foot deformity that usually occurs at the joint at the base of the big toe. A bunion is actually a bony growth at the joint. It forms when the big toe is forced in toward the rest of the toes, causing the head of the first metatarsal bone to jut out and rub against the side of the shoe. The underlying tissue becomes inflamed, and a painful bump forms.

Treatment: Acute Gout Attack

Acute attacks of gout and long-term treatment of gout and hyperuricemia require different approaches. Treatment usually involves medication. After the first attack, some health care providers advise patients to keep a supply of medicines on hand to take at the first sign of symptoms of a second attack.

Treatments are prescribed for conditions associated with gout, including uric acid nephropathy and uric acid nephrolithiasis.

Supportive measures include applying ice and resting the affected joint.

Many patients do not require medication. Often lifestyle and dietary measures are enough to prevent attacks. Measures include not eating foods high in purines, not drinking alcohol, and maintaining a healthy weight.

Medicines for gout attacks are aimed at relieving pain and reducing inflammation. These include:

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- Colchicine

- Corticosteroids

These medicines may be combined to treat a gout attack.

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

NSAIDs are the medicines of choice for an acute attack in younger, healthy patients with no serious health problems, such as disease of the kidneys, liver, or heart.

Many NSAIDs are available. Over-the-counter NSAIDs include ibuprofen, naproxen, and ketoprofen.

Indomethacin is a prescription NSAID. It is often the first choice of treatment. Usually 2 to 7 days of high-dose indomethacin is enough to treat a gout attack.

Regular use of NSAIDs can cause health problems, such as ulcers and gastrointestinal bleeding. Patients should follow instructions exactly on how much to take and for how long to avoid such health problems.

Patients with diabetes who take medicines to lower glucose by mouth may need to adjust their dosage if they also take NSAIDs. This is because of possible harmful interactions between these medicines.

Patients with kidney disease or limited kidney function should not use NSAIDs.

Colchicine

Colchicine is a derivative of the autumn crocus (meadow saffron). It has been used for gout attacks for centuries. It is very effective in relieving a gout attack. It should not be used by older patients or those with kidney, liver, or bone marrow disorders. Colchicine may affect fertility. This medicine should not be used during pregnancy. Colchicine should be started soon after the gout attack begins and the initial therapy is 3 tablets (2 tablets immediately and a 3rd tablet after 1 hour). In many cases, physicians will recommend follow up therapy starting the following day which consists of 1 tablet every 12-24 hours until gout symptoms resolve.

Certain medicines can interact with colchicine such as some antibiotics and stomach acid reducers (H2 blockers).

Patients should tell their doctor about all other medicines they are taking before being prescribed colchicine.

"Difficult" Gout

This term applies to people whose acute attack of gout occurs in multiple joints or in the presence of disease of the kidneys, heart, or in other conditions where using NSAIDs or colchicine should be avoided.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids may be used in patients who cannot tolerate NSAIDs such as the older or those with kidney disease. Corticosteroid injections into an affected joint provide relief for many patients. Steroids taken by mouth may be used for patients who cannot take NSAIDs or colchicine and who have gout in more than one joint.

Biologic Compounds

These are new agents that target a key chemical released during acute gout called interleukin-1 (IL-1). These compounds are not currently approved by the FDA for gout therapy.

Anakinra, given as a daily injection, has been evaluated for treating difficult gout. Anakinra is FDA approved for other indications, but it is not FDA approved for gout. While it is an expensive therapy with significant risk of developing side effects, it can be used for gout in specific circumstances.

Canakinumab is also effective for acute, difficult gout. However, the FDA has not approved this drug at this time due to risk for adverse effects.

Rilonacept (IL-1Trap) injection is being studied to see if it can help reduce gout flares during initiation of uric acid-lowering therapy (ULT) with allopurinol. More research is necessary to confirm the early positive results, its long-term safety, and the patients most likely to benefit. It is not yet FDA approved.

Medicine to Lower Blood Uric Acid Level

People already taking urate-lowering medicine will likely continue taking this medicine during an attack. Starting a new urate lowering medicine should occur after the acute attack is under control.

Treatment: Preventing Attacks

Between Attacks

After an acute attack some patients remain at high risk for another attack for several weeks during the intercritical period. Such patients include those with kidney insufficiency or those with congestive heart failure who are on diuretics. Colchicine or NSAIDs may be used for 1 to 2 months or longer to prevent another attack.

Long-term Prevention of Attacks

The cause of gout is hyperuricemia. Lifestyle changes should be recommended for all patients with gout, including weight loss if obese, dietary changes, and reducing alcohol intake. If the uric acid remains elevated in spite of these recommendations, medicine that lowers uric acid level in the blood or that block uric acid production to prevent gout attacks and other complications is usually prescribed.

Hyperuricemia that causes no symptoms may not need to be treated with medicine. Asymptomatic hyperuricemia often does not lead to gout or other health problems.

Before treatment, a 24-hour urine collection sample may be ordered for patients with frequent gout attacks. This is to determine whether they are over-producers or under-excreters of uric acid.

Low doses of NSAIDs or colchicine are used during several months after starting urate-lowering medicine to prevent gout attacks.

Initiation of long-term treatment of hyperuricemia is not currently recommended by the American College of Rheumatology for most people who have had only one gout attack. It is however recommended for people who have had an attack of gout and any of the following:

- Tophi on exam or by imaging

- History of kidney stones

- Chronic kidney disease of any sort

There are several reasons people with gout and kidney disease should be started on urate-lowering medications with only one attack of gout.

- They usually have hyperuricemia due to the kidney disease.

- Treating acute gout is more difficult with kidney disease.

- Urate-lowering medicines such as allopurinol may protect the kidneys from worsening kidney disease.

First line recommended therapies to lower uric acid include allopurinol or febuxostat.

Allopurinol

Allopurinol decreases uric acid production by blocking an enzyme called xanthine oxidase. It is the drug most often used in long-term gout treatment for older patients, in patients with kidney disease, and those who overproduce uric acid.

When it is first started, allopurinol can trigger further attacks of gout. Therefore, a low dose is used first. During the first months or longer, the patient also takes an NSAID or colchicine to reduce that possibility. Allopurinol is generally well tolerated but may cause side effects in some people, especially people of Chinese, Thai, or Korean heritage. A gene test called HLA B-58:01 is recommended in such individuals before starting allopurinol.

Allopurinol has positive effects on hypertension, heart, and kidney disease, so it may be better than other medicines for patients with both gout and these conditions. Possible interactions with other medicines and allopurinol should be discussed with your physician before taking the medicine.

Febuxostat

Febuxostat is a newer drug and is particularly useful for patients who are allergic to allopurinol or who cannot tolerate higher doses of allopurinol. Like allopurinol, it blocks xanthine oxidase, and gout may flare up after starting the medication. The dose of febuxostat does not need to be adjusted in people with kidney disease. The FDA has added a boxed warning for febuxostat after studies showed an increased risk of heart-related death with febuxostat compared with allopurinol. The FDA continues monitoring this drug for hypersensitivity reactions. It is much more expensive than allopurinol.

Uricosurics

Uricosurics are alternative first-line therapies. These drugs prevent the kidney from reabsorbing uric acid, and therefore, increase the amount excreted in the urine. They may be used when the kidneys are not eliminating enough uric acid which is present in about 80% of gout cases. The doctor will check a 24-hour urine sample to diagnose this problem. These medicines are not used for patients with reduced kidney function or those with tophaceous gout.

Other patients who may benefit from uricosurics include:

- Under 60 years of age

- Normal diets

- Normal kidney function

- No risk for kidney stones

NSAIDs, particularly aspirin and similar medicines, reduce the effectiveness of uricosurics. Patients taking uricosurics should avoid NSAIDs if possible.

Probenecid

Probenecid is an older medicine developed in the 1950s. It may be useful in patients who cannot take other gout medications. It is generally well tolerated.

Lesinurad

Lesinurad (Zurampic) is a newer FDA-approved uricosuric agent. It is used together with urate-lowering therapy (like allopurinol or febuxostat) in patients with gout for whom urate-lowering therapy alone was insufficient in reaching normal uric acid levels. A combination therapy of lesinurad and allopurinol (Duzallo) is also available. Lesinurad is not indicated in asymptomatic hyperuricemia or in patients with poor kidney function. Lesinurad was taken off the market in February 2019 for business reasons and not for safety reasons.

Pegloticase

Pegloticase (Krystexxa, formerly Puricase) is a recombinant form of the uricase enzyme that breaks down uric acid so it is removed through the urine. Pegloticase injections are given intravenously every two weeks and are reserved for patients with severe chronic gout who have not been helped by first-line treatments. Mild to severe reactions are possible. The FDA recommends that an antihistamine and corticosteroid be given prior to the injection to prevent reactions and that other urate-lowering medicines be stopped. Several side effects are possible, some of which can be severe. It has not been tested in patients with heart failure. Pre-infusion testing can be done to identify patients at a higher risk for an adverse reaction to pegloticase.

Information About Medicines for Gout

Starting medicines which lower uric acid can set off an attack of gout. You should work with your doctor to learn which medicines and dosages may cause gout flare-ups. In general, it is best to increase the dose slowly over many weeks. Also, you may need a medicine such as colchicine to prevent gout flares for the first several months after starting the urate-lowering medicine. Your uric acid should be lowered to less than 6.0 mg/dL, and sometimes less than 5.0 mg/dL. Gout medications may interact with other drugs. Most people with gout will need to take the urate-lowering medicine for the rest of their life.

Other Medications

People with gout have a high risk for high blood pressure (hypertension). Some medicines for hypertension, such as thiazide diuretics, beta-blockers, or ACE inhibitors can increase the risk of developing gout attacks. Other medicines, such as calcium channel blockers, may have beneficial effects on both high blood pressure and gout.

Other Treatments

Surgery

Large tophi that are draining, infected, or interfering with the movement of joints may need to be surgically removed. Surgery may not be suitable for people with other medical conditions such as infection. In most cases, measures such as taking medicines that lower uric acid should reduce the need for surgery.

Other types of surgeries are available to relieve joint pain and improve joint function. In some cases, joint replacement is needed.

Rest and protecting the affected joint with a splint can also promote recovery. Applying ice packs during an acute attack can help relieve symptoms.

Lifestyle Changes

Dietary Recommendations

Uric acid level is only mildly affected by diet. Therefore, dietary therapy does not play a large role in preventing gout. Still, avoiding or reducing foods rich in purine can help.

Foods and drinks to avoid:

- Organ meats (liver, kidney, heart, sweetbread)

- High fructose corn syrup (in foods and drinks such as most sugary sodas)

- Alcohol during gout attacks

Foods and drinks to limit:

- Beef, pork, lamb

- Seafood rich in purine (shellfish, sardine, anchovy, tuna, herring)

- Alcohol, especially beer and hard liquor

- Fruit juices or sweet fruits

Eating a moderate amount of purine-rich vegetables (spinach, cauliflower, mushrooms, and legumes) does not seem to increase the risk of developing gout.

Dairy products, especially low-fat products, may actually protect against gout. Drinking coffee may also have a preventive effect against gout. Taking folic acid and vitamin C may reduce uric acid level.

Drinking plenty of water helps remove uric acid from the body.

Alcohol, especially beer and hard liquor, raises uric acid level, which can lead to gout attacks. This is why so many people who drink an excessive amount of alcohol have gout attacks. Drinking wine occasionally does not seem to be linked to an increase in gout attacks.

Fructose-rich diets, including soda and fruit juice, may increase the risk of developing gout.

Maintaining a Healthy Weight

A supervised weight-loss program may be effective in reducing uric acid level in overweight people. Crash dieting, though, can have the opposite effect because it can increase uric acid level, causing an acute attack.

Medications

Medications to treat other conditions can increase uric acid level. For example, certain diuretics (water pills) and low dose daily aspirin can affect uric acid level. Switching to alternative treatments may be necessary.

Avoid Joint Injury

People with gout should avoid activities that cause repetitive joint trauma such as wearing tight shoes.

Preventing an Attack During Travel

Travel may increase the risk for gout attacks. Travel not only increases stress but eating and drinking patterns may change. Before traveling, patients should discuss preventive measures with their health care provider. The doctor may prescribe taking a corticosteroid at the first sign of a gout attack. In most cases, this stops the attack.

Complications

Properly treated gout by lowering uric acid to less than 6.0 mg/dL is in effect "curable" and rarely poses a long-term health threat, though during an attack the pain can be disabling.

Pain and Disability

Left untreated, gout can develop into a painful and disabling chronic disorder. Persistent gout can destroy cartilage and bone. This causes deformed joints and loss of motion. If gout is not treated, tophi can grow to the size of golf balls and destroy bone and cartilage in the joints. This is similar to the process in rheumatoid arthritis. In very severe cases, joint destruction results in complete disability.

Kidney Conditions

Kidney Stones

Kidney stones can occur after the development of hyperuricemia. Although the stones are usually made of uric acid, they may also be mixed with other materials.

Kidney Disease

Patients with chronic hyperuricemia may develop chronic kidney disease, which may lead to kidney failure. This is because a constant high level of uric acid can damage the kidneys. Therefore, any patient with gout and hyperuricemia should be treated with urate-lowering medication.

Gout and Heart Disease

Gout is found in higher rates in people with high blood pressure, coronary artery disease, or heart failure. A high level of uric acid has been linked to a high risk for death from heart conditions. Studies have also found an association between gout and having metabolic syndrome. This is a collection of health problems, including abdominal obesity, high blood pressure, high triglyceride levels, and low HDL (good) cholesterol level. This syndrome increases a person's risk of developing heart disease and diabetes. Studies are being done to find out whether treating asymptomatic hyperuricemia in such people is beneficial.

Other Medical Conditions Linked to Gout

Other conditions that are linked to long-term gout:

- Cataracts

- Dry eye syndrome

- Complications in the lungs (in rare cases, uric acid crystals occur in the lungs)

Resources

- American College of Rheumatology -- rheumatology.org

- Arthritis Foundation -- www.arthritis.org

- Gout & Uric Acid Education Society -- gouteducation.org

- National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases -- www.niams.nih.gov

References

Burns CM, Wortmann RL. Clinical features and treatment of gout. In: Firestein GS, Budd RC, Gabriel SE, McInnes IB, O'Dell JR, eds. Kelley and Firestein's Textbook of Rheumatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017:chap 95.

Choi HK. Epidemiology and classification of gout. In: Hochberg MC, Gravallese EM, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, Weinblatt ME, Weisman MH, eds. Rheumatology. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019:chap 189.

Dalbeth N, McLean L. Etiology and pathogenesis of gout. In: Hochberg MC, Gravallese EM, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, Weinblatt ME, Weisman MH, eds. Rheumatology. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019:chap 190.

Edwards NL. Crystal deposition diseases. In: Goldman L, Schafer AI, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 26th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2020:chap 257.

FitzGerald JD, Dalbeth N, Mikuls T, et al. 2020 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Management of Gout. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72(6):879-895. PMID: 32390306 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32390306/.

Hainer BL, Matheson E, Wilkes RT. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of gout. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90(12):831-836. PMID: 25591183 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25591183/.

Harris JC. Disorders of purine and pyrimidine metabolism. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 108.

Keenan RT, Krasnokutsky S, Pillinger MH. Etiology and pathogenesis of hyperuracemia and gout. In: Firestein GS, Budd RC, Gabriel SE, McInnes IB, O'Dell JR, eds. Kelley and Firestein's Textbook of Rheumatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017:chap 94.

Keenan RT. Limitations of the current standards of care for treating gout and crystal deposition in the primary care setting: a review. Clin Ther. 2017;39(2):430-441. PMID: 28089200 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28089200/.

Mikuls TR. Urate-lowering therapy. In: Firestein GS, Budd RC, Gabriel SE, McInnes IB, O'Dell JR, eds. Kelley and Firestein's Textbook of Rheumatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017:chap 66.

Neogi T, Jansen TL, Dalbeth N, et al. 2015 Gout classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(10):1789-1798. PMID: 26359487 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26359487/.

On PC. Lesinurad (Zurampic) for Gout. Am Fam Physician. 2018;97(6):374-375. PMID: 29671542 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29671542/.

Perez-Ruiz F, Dalbeth N. Gout. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2019;45(4):583-591. PMID: 31564298 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31564298/.

Qaseem A, Dallas P, Forciea MA, Starkey M, Denberg TD; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Dietary and pharmacologic management to prevent recurrent nephrolithiasis in adults: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(9):659-667. PMID: 25364887 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25364887/.

Qaseem A, McLean RM, Starkey M, Forciea MA; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Diagnosis of acute gout: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(1):52-57. PMID: 27802479 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27802479/.

Qaseem A, Harris RP, Forciea MA; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Management of acute and recurrent gout: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(1):58-68. PMID: 27802508 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27802508/.

Schlesinger N. Clinical features of gout. In: Hochberg MC, Gravallese EM, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, Weinblatt ME, Weisman MH, eds. Rheumatology. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019:chap 191.

Shekelle PG, Newberry SJ, FitzGerald JD, et al. Management of gout: a systematic review in support of an American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(1):37-51. PMID: 27802478 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27802478/.

Terkeltaub R. Management of gout and hyperuricemia. In: Hochberg MC, Gravallese EM, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, Weinblatt ME, Weisman MH, eds. Rheumatology. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019:chap 192.

|

Review Date:

6/29/2020 Reviewed By: Diane M. Horowitz, MD, Rheumatology and Internal Medicine, Northwell Health, Great Neck, NY. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team. |