Ovarian cancer - InDepth

Highlights

Ovarian Cancer

Ovarian cancer is a cancer that develops in a woman's ovary. It can be difficult to detect in its early stages. Unlike cervical and breast cancers, there are currently no effective screening methods for ovarian cancer. The majority of women are diagnosed when the cancer is in an advanced stage.

If you are diagnosed with ovarian cancer, you should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist, a doctor who specializes in diagnosing and treating cancers of the female reproductive system. Outcomes are best when women receive care in hospitals and from doctors with experience treating ovarian cancer.

Risk Factors

The main risk factors for ovarian cancer are:

- Genetic mutations, principally BRCA1 or BRCA2

- Family history of ovarian, breast, or hereditary colorectal cancer

- Older age

- Not having had children

Protective Factors

Factors that may help reduce the risk for ovarian cancer include:

- Birth control pills.

- Childbirth and breastfeeding.

- Tubal ligation (tying fallopian tubes) or hysterectomy (removal of uterus) after childbearing.

- Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy surgery (removal of both ovaries and fallopian tubes) for women with BRCA and other genetic mutations who are at high risk for ovarian cancer.

BRCA Genetic Mutations

Guidelines from the United States Preventive Service Task Force recommend screening for BRCA genetic mutations in women whose family history suggests a high risk for ovarian cancer. Mutations in the genes called BRCA1 and BRCA2 are among the strongest risk factors for ovarian and breast cancers. Women who do not have risk factors do not need to be screened for these gene mutations, but are still at risk of developing ovarian cancer. All women with a diagnosis of ovarian cancer should undergo genetic testing for BRCA and potentially other genetic abnormalities regardless of family history.

Your health care provider may estimate your risk for these genes using a questionnaire. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has also developed an on-line screening resource (Know:BRCA Tool) that women can use to understand their risks. Having several first-degree or second-degree relatives who have had breast, ovarian, fallopian tube, or peritoneal cancers is an indication of risk.

If you are at risk, you may be referred to a genetic counselor who can review your history and discuss with you whether you should be tested for these genetic mutations.

Recent Drug Approvals

The FDA approved rucaparib (Rubraca), niraparib (Zejula), and olaparib (Lynparza) for some patients with BRCA-mutated ovarian cancer. These drugs block an enzyme called PARP, which is used by cells to repair damage to their DNA. Inhibiting PARP makes these cells more sensitive to treatment with other chemotherapy drugs.

Introduction

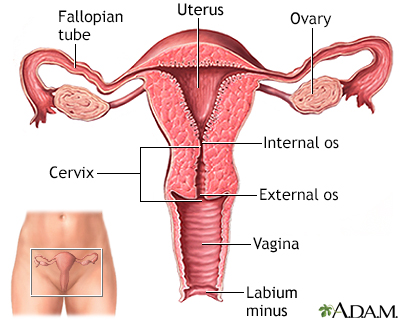

Ovarian cancer is a cancer that begins in a woman's ovary, although there is information accumulating that many ovarian cancers may actually begin in the fallopian tube with very early spread to the ovary. The ovaries produce eggs (ova), and the hormones estrogen and progesterone. A woman's reproductive system includes the:

- Ovaries

- Fallopian tubes

- Uterus

- Cervix

- Vagina

The ovaries are two small, almond-shaped organs located on either side of the uterus. Each ovary is attached to a fallopian tube. Both fallopian tubes connect to the uterus. During a woman's monthly reproductive cycle, an egg is released by an ovary, and travels down the fallopian tube towards the uterus to await fertilization.

The uterus, commonly called the womb, is a hollow muscular organ located in the female pelvis between the bladder and rectum. The ovaries produce the eggs that travel through the fallopian tubes. Once the egg has left the ovary it can be fertilized and implant itself in the lining of the uterus. The main function of the uterus is to nourish the developing fetus prior to birth.

Ovarian Cancers

Ovarian cancers begin when cells in an ovary grow abnormally quickly and develop into a tumor. Some tumors are benign (non-cancerous). Others are malignant (cancerous.) Ovarian tumors may be either solid or cystic (fluid-filled sacs). They can look very similar in appearance to benign ovarian cysts, which are very common, and this can make early diagnosis difficult.

Ovarian cancers can develop in the different types of cells that make up the ovary. They are usually one of three types:

Epithelial

tumors are the most common type of ovarian cancer, and the main focus of this report. These cancers originate in the layer of cells that cover the outside of the ovaries.Germ cell

tumors are much less common. They begin in the ovary's egg production cells. These cancers, although rare, tend to occur in younger women and children.Stromal

tumors are rare. They develop from the connective tissue cells that hold the ovary together. These cells produce the female hormones estrogen and progesterone.

Ovarian Cancer Progression

Ovarian cancer progresses almost silently, usually with only vague, non-specific symptoms. By the time serious symptoms do appear, the ovarian tumor may have grown large enough to shed cancer cells throughout the abdomen. At such an advanced stage, the cancer is more difficult to treat and cure.

As ovarian cancer advances, cells from the original tumor can spread (metastasize) throughout the pelvic and abdominal regions and travel to other parts of the body. Cancer cells are carried through the body through lymph vessels and the bloodstream.

Risk Factors and Prevention

Ovarian cancer is the fifth leading cause of cancer death in women. Each year in the United States, about 22,000 women are diagnosed with ovarian cancer. About 14,000 American women die each year from this disease.

Certain factors increase the risk for ovarian cancer, while other factors reduce risk. Inherited genetic mutations of BRCA genes are the strongest risk factor. A family history of breast or ovarian cancer is also a strong risk factor.

Many of the preventive factors are related to the number of times a woman ovulates during her lifetime, which is indicated by the number of menstrual periods she has. Fewer menstrual periods and ovulations appear to be associated with reduced risk for ovarian cancer.

Risk Factors for Ovarian Cancer

Age

Older women have a higher risk for ovarian cancer than younger women. Ovarian cancer usually occurs after menopause, although it can develop in women of all ages. Most women diagnosed with ovarian cancer are older than age 55.

Ethnicity

Ovarian cancer is more common in white women than in African-American women. Women who are of Ashkenazi (Eastern European) Jewish descent have a higher risk of developing ovarian cancer in part due to a higher risk of BRCA abnormalities in this population.

Family History

Women are at high risk for ovarian cancer and for harboring a genetic mutation such as BRCA if they have a:

- First-degree relative (mother, sister, or daughter) with ovarian cancer at any age. The risk increases with the number of affected first-degree relatives.

- First-degree relative or two second-degree relatives (aunts or grandmothers) on the same side who had breast cancer before age 50 years.

- Family member with both breast and ovarian cancer.

- Family history of male breast cancer.

- Family history of hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer known as Lynch syndrome.

When a woman describes her family history to her doctor, she should include the history of cancer in women on both the mother's and the father's side. Both are significant.

Genetic Mutations

Inherited mutations in the genes called BRCA1 and BRCA2 greatly increase the risk for ovarian and breast cancers. While these mutations are more common among women of Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry, they can occur in women of any ethnicity.

Women with a BRCA1 mutation have about a 44% lifetime risk for ovarian cancer. Women with a BRCA2 mutation have about a 17% lifetime risk for ovarian cancer. (By contrast, the lifetime ovarian cancer risk for women in the general public is about 1 in 55 or 1.3%.) These gene mutations are also associated with increased risks for breast cancer, fallopian tube cancer, pancreatic cancer, and prostate cancer in the male. In addition to an increased lifetime risk, women with these gene mutations tend to develop these cancers at an earlier age than that seen in the usual population of women with ovarian cancer.

Other genetic factors are also associated with increased risk. Women who have genetic mutations associated with hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC or Lynch syndrome) have about a 10% to 15% lifetime risk of developing ovarian cancer.

Personal Medical History

Women who have been diagnosed with breast cancer are at increased risk for ovarian cancer, even if they do not have BRCA mutations. Endometriosis, a condition in which the cells that line the cavity of the uterus grow in other areas of the body such as on the ovaries or on the other pelvic structures, increases the risk for ovarian cancer.

Reproductive History

Women are at increased risk for ovarian cancer if they began menstruating at an early age (before age 12), have not had any children, had their first child after age 35, or experienced early menopause (before age 50).

There are also preventive factors associated with reproductive history. The more times a woman gives birth, the less likely she is to develop ovarian cancer. Breast-feeding for a year or more after giving birth may also decrease ovarian cancer risk.

Tubal ligation, a method of sterilization that ties off the fallopian tubes, is associated with a decreased risk for ovarian cancer. Similarly, hysterectomy, the surgical removal of the uterus, may decrease risk.

Hormone Use

Women who use hormone therapy (HT) after menopause for longer than 5 years may have an increased risk for ovarian cancer. The risk seems to be particularly significant for women who take estrogen-only HT. The risk is less clear for combination estrogen-progestin HT.

Oral contraceptives (birth control pills) significantly reduce the risk of ovarian cancer, in some series by as much as 50%. The longer a woman takes oral contraceptives the greater the protection and the longer protection lasts after stopping oral contraceptives.

Obesity

Women who are obese have an increased risk for ovarian cancer.

Preventive Strategies for Women at High Risk

Women with a strong family history of ovarian or related cancers should discuss preventive strategies with their providers.

Screening for BRCA Genetic Mutations

Guidelines from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommend BRCA screening for women at high risk for ovarian cancer due to personal or family history. The USPSTF does not recommend routine genetic screening or testing in women whose family history does not suggest BRCA mutations. Having several first-degree or second-degree relatives who have had breast, ovarian, fallopian tube, or peritoneal cancers is an indication of risk. Having a male family member with breast cancer is also an indication of risk.

Your provider can screen you using a questionnaire that evaluates your family and personal medical history, and other factors. If your provider decides you are at risk, you may be referred to a genetic counselor who can review your history and discuss with you whether you should be tested for the BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations, or for other genetic mutations that may be present and are also associated with increased risks.

The genetic test uses DNA from a blood or saliva sample to check for these mutations. A positive test means that the mutations are present. It does not, however, mean that a woman will definitely develop ovarian or breast cancer. A negative test does not mean that a woman will never get ovarian cancer.

Removal of Ovaries (Oophorectomy)

Surgical removal of the ovaries called oophorectomy, significantly reduces the risk for ovarian cancer. When it is used to prevent cancer, the procedure is called a prophylactic oophorectomy.

Prophylactic oophorectomy is approximately 85% to 95% protective against ovarian cancer and is recommended for women at high risk for ovarian cancer. These women generally have the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genetic mutation, or have two or more first-degree relatives who have had ovarian cancer.

Bilateral oophorectomy is the removal of both ovaries. Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is the removal of both fallopian tubes plus both ovaries. Evidence is accumulating that many ovarian cancers actually arise in the fallopian tubes and secondarily involve the ovary. There is strong evidence that salpingo-oophorectomy is very effective in reducing risk for ovarian cancer in women who carry the BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation.

Primary peritoneal carcinoma, a rare cancer that develops in the peritoneum (the thin membrane that lines the inside of the abdomen and gives rise to the epithelial lining of the ovary), can still develop in women who have their ovaries and tubes removed. Some of these peritoneal cancers may actually come from small tumors that originated in the fallopian tubes. Some evidence suggests that preventive salpingo-oophorectomy may reduce the risk for peritoneal cancer and fallopian tube cancers, in addition to ovarian cancer.

Oophorectomy causes immediate menopause, which can raise health concerns for premenopausal women. You should discuss all the risks and benefits of prophylactic oophorectomy with your health care team, as well as the option for hormone therapy after surgery.

Symptoms

Ovarian cancer used to be considered a "silent killer." Symptoms were thought to appear only when the cancer was in an advanced stage. Evidence now suggests that even early-stage ovarian cancer can produce symptoms.

Ovarian cancer grows quickly and can progress from early to advanced stages within a year. Paying attention to symptoms can help improve a woman's chances of being diagnosed and treated promptly. Detecting cancer while it is still in its earliest stages may help improve prognosis.

See your provider if you have the following symptoms on a daily basis for more than a few weeks:

- Bloating or swollen belly area

- Pelvic or lower abdominal pain or feeling of heaviness

- Difficulty eating or feeling full quickly

Other symptoms that are sometimes associated with ovarian cancer include:

- Menstrual irregularities

- Fatigue

- Indigestion

- Constipation

- Urinary urge or frequency

- Back pain

- Pain during sexual intercourse

- Feeling a mass in the abdomen

Be aware that these symptoms are very common in women who do not have cancer and are not specific for ovarian cancer. While prompt follow-up with your provider is important when one or more of these are present, there are many other explanations for these symptoms besides ovarian cancer.

Based on symptoms and physical examination, your provider may order pelvic imaging tests or blood tests. If these tests reveal possible signs of cancer, you should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist.

Diagnosis

Ovarian cancer is difficult to detect in its early stages. Unlike Pap tests for cervical cancer or mammogram for breast cancer, there is currently no effective screening method for ovarian cancer.

Imaging tests, such as transvaginal ultrasound, and blood tests, such as CA-125, HE4, or OVA-1, have not proven to be useful screening tools. Studies indicate that screening with these tests does not reduce ovarian cancer mortality and may cause women to undergo unnecessary medical and surgical treatment due to their high rate of "false positives."

The United States Preventive Services Task Force and other medical associations do not recommend routine screening for ovarian cancer in women who do not have signs or symptoms of the disease. However, if your provider thinks you may have ovarian cancer, these tests can help in diagnosis. Some diagnostic tests are also used in the treatment process.

Pelvic Exam

Physical signs indicating ovarian cancer may be detected during a pelvic exam. A pelvic exam is performed in two ways. The doctor inserts one or two fingers into the vagina while feeling the abdomen with the other hand. The doctor may also perform a rectovaginal exam, which involves the insertion of one finger into the vagina and another into the rectum.

Both exams enable the doctor to evaluate the size and shape of the ovaries. Enlarged ovaries and abdominal swelling can be signs of ovarian cancer. A mass felt during a pelvic exam often requires further evaluation by ultrasound and sometimes requires surgery to make a definitive diagnosis.

Not all masses felt are cancerous. They may be benign conditions such as ovarian cysts or uterine fibroids.

Transvaginal Ultrasound and Other Imaging Tests

Ultrasound

Transvaginal ultrasound is a noninvasive diagnostic procedure that uses sound waves to bounce off tissues, organs, and masses in the pelvic area. It creates a visual picture of the ovaries, cervix, and uterus.

A probe, called a transducer, placed in the vagina sends out the sound waves. The echoes are collected and converted into a picture of the area. The image can help evaluate the size and internal structure of the ovaries and distinguish a solid mass (like ovarian cancer) from fluid-filled masses (like ovarian cysts.)

Transvaginal ultrasound does not provide enough specific information to reliably determine whether abnormal masses are cancerous. This test is not helpful as a screening tool for women who do not have signs of ovarian cancer.

Other Imaging Techniques

Other imaging tests are less common for the diagnosis or evaluation of suspected ovarian cancer but, in patients who appear to have ovarian cancer, they may help determine if cancer has spread to other parts of the body. They include:

- Chest x-ray

- Computed tomography (CT) scan

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- Positron emission tomography (PET) scan

- Colonoscopy

CA-125 and Other Blood Tests

CA-125 Blood Test

CA-125 is a protein that is secreted by ovarian cancer cells and is elevated in over 80% of women with ovarian cancer. A blood test for this protein is usually ordered only if ovarian cancer is strongly suspected or has been diagnosed. In general, a CA-125 level is considered to be normal if it is less than 35 U/mL (units per milliliter). The test may also be useful for evaluating tumor growth and predicting survival in people with recurrent cancer.

The test is not useful for diagnosis or early screening, because it might increase in many other conditions. In about one half of women with very early ovarian cancer, CA-125 levels are not elevated above the normal standard. Furthermore, an elevated level can be caused by a number of other conditions including:

- Kidney, heart, or liver problems

- Other cancers

- Infections

- Endometriosis

- Adenomyosis

- Fibroids

- Pregnancy

Biopsy

A biopsy (tissue sample) is the only way to confirm a diagnosis of ovarian cancer. Biopsies for ovarian cancer are performed through exploratory surgery. A gynecological oncologist should perform this surgery. There are several surgical approaches:

Laparotomy

is an open surgery procedure that usually requires general anesthesia. The surgeon makes an incision in the abdomen either from the pubic bone to the navel or transversely in the lower abdomen (bikini incision) to explore the abdominal cavity.Laparoscopy

also requires general anesthesia but uses only small incisions. A lighted tube with a camera on the end is inserted. Robotically assisted laparoscopy may be employed as well.

The surgeon will take tissue samples and remove the tumor. The surgeon will also examine the organs and evaluate the spread of the cancer. Other surgical procedures, such as hysterectomy, removal of lymph nodes, appendectomy, omentectomy (removal of fatty tissue hanging from the colon) or even removal of parts of the intestine may also be performed.

The tissue samples are sent to a pathology lab for testing. If the test results indicate cancer, the woman may have additional imaging tests to see how far the cancer has spread. Based on biopsy and imaging tests, the cancer is staged.

Staging and Prognosis

Ovarian cancer is staged based on:

- The size and location of the primary Tumor (T)

- If the tumor has spread to the lymph Nodes (N)

- If the cancer has spread (metastasized) to other parts of the body (M)

The TNM system is used to classify cancer in stages I to IV. Each stage is further divided into substages.

Stages of Ovarian Cancer

Stage I

In stage I, the cancer has not spread. It is confined to one ovary (stage IA) or both ovaries (stage IB). In stages IA and IB, the ovarian capsules are intact, and there are no tumors on the surface. Stage IC can affect one or both ovaries, but the tumors are on the surface, or the capsule (outer covering of the ovary) has burst, or there is evidence of tumor cells in abdominal fluid (ascites).

Stage II

In stage II, the cancer is in one or both ovaries and has spread to other areas in the pelvis. It may have advanced to the uterus or fallopian tubes (stage IIA), or other areas within the pelvis such as the bladder, colon or rectum (stage IIB), but is still limited to the pelvic area.

Stage III

In stage III, the cancer is in one or both ovaries and has spread outside of the pelvis to nearby abdominal regions or lymph nodes. In Stage IIIA, microscopic amounts of cancer are in the peritoneum (the lining of the abdomen) or involve the lymph nodes. In Stage IIIB, the cancer is visually detectable in the peritoneum, with masses up to 2 cm in size with or without lymph node involvement. In Stage IIIC, the cancer has grown larger in the peritoneum, greater than 2 cm in size, with or without lymph node involvement.

Stage IV

Stage IV is the most advanced cancer stage. In Stage IVA, the cancer has spread to the fluid around the lungs. In Stage IVB, the cancer has spread to the liver or spleen or to other distant organs such as the lungs, brain, and bones.

Prognosis

Survival rates for ovarian cancer vary depending on many different factors, including the age of the woman and the stage at the time of diagnosis. Unfortunately, most cases with ovarian cancer are not diagnosed until the disease is advanced and has metastasized. In general, 75% of women survive ovarian cancer at least 1 year after diagnosis.

A 5-year survival rate is an estimate based on the percentage of people who are still alive 5 years after their cancer is diagnosed. Survival rates are slightly different for epithelial, germ cell, and stromal ovarian cancer, but on average:

- 5-year survival rates are over 90% if the cancer is still confined to the ovary at diagnosis. However, only 15% of ovarian cancers are found at this stage.

- For Stage II cancer, the 5-year survival rate is approximately 65% to 70%.

- For Stage III cancer, the 5-year survival rate is approximately 36% to 46%.

- If the cancer has spread to sites outside the pelvis, the 5-year survival rate is below 20%.

Treatment

Surgery is the initial treatment for most women with suspected ovarian cancer. Surgery is usually followed by chemotherapy. The course of treatment is determined by the stage of the cancer. Clinical trials investigating new types of treatments are an option for all stages of ovarian cancer.

It is very important that women with ovarian cancer seek care from a qualified gynecologic oncologist (a surgical specialist in female reproductive cancers) and a qualified medical oncologist with special expertise in the chemotherapeutic management of gynecologic cancer. Many gynecologic oncologists also have expertise in chemotherapeutics and provide this aspect of care as well.

Studies indicate that it is best for people, especially those with advanced-stage ovarian cancer, to receive care at medical centers that specialize in cancer treatment and surgery. Outcomes are best when women receive care from hospitals and doctors who treat a large number of ovarian cancer cases.

Women of child-bearing age should discuss with their cancer team any concerns and questions they may have about how various treatments could affect their fertility. They may also wish to have a consultation with a fertility specialist. Assisted reproductive technology such as embryo or oocyte (egg) cryopreservation ("freezing") may offer some women an option to later have children. It is very important that you have these discussions with your health care team before you begin cancer treatment.

Treatment for Stage I and Stage II Ovarian Cancers

Treatment options for stage I and stage II ovarian epithelial cancer may include:

- Surgical removal of the uterus (total hysterectomy), removal of both ovaries and fallopian tubes (bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy), partial removal of the omentum (omentectomy), and surgical staging of the lymph nodes and other tissues in the pelvis and abdomen.

- Unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (removal of a single ovary and fallopian tube) and preservation of the uterus and opposite tube and ovary may be a fertility-sparing option for select premenopausal women with cancer confined to a single ovary.

- Clinical trials with radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or new treatments.

Treatment for Stage III and Stage IV Ovarian Cancers

Treatment options for stage III and stage IV ovarian epithelial cancer may include:

- Surgical removal of the tumor (debulking), total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oopherectomy, and omentectomy. Any affected areas or organs will be removed to minimize the amount of disease remaining at the conclusion of surgery.

- Chemotherapy before surgery (neoadjuvant chemotherapy). In some cases, the size or location of the tumors, or the woman's medical condition, may reduce the chance for a successful debulking surgery. In these circumstances, upfront chemotherapy may be given to shrink the tumor, or help the woman improve medically, so that a successful surgery can be performed. It would appear that outcomes are similar for upfront chemotherapy followed by surgery after 2 to 3 cycles of chemotherapy versus initial surgery followed by chemotherapy.

- Combination chemotherapy with a platinum-based drug and a taxane drug delivered intraperitoneally (through the abdominal cavity) or intravenously (through a vein).

- Clinical trials of biologic drugs (targeted therapy) following combination chemotherapy.

Treatment for Recurrent Ovarian Cancer

If ovarian cancer returns or persists after treatment, chemotherapy is the main treatment. Surgery may also be performed to attempt an interval debulking, or to resolve such issues as urinary or intestinal blockages. Repeat surgical resections are best performed if limited areas of recurrent disease are seen and if the recurrence occurs longer than a year after completion of the last course of chemotherapy. Radiation therapy may be used to provide symptom relief. Clinical trials are investigating targeted therapy and hormone therapy.

Follow-Up after Treatment

After treatment is completed, you should have regular follow-up visits and tests to monitor your health and to check for any signs of cancer recurrence.

Recommended tests include:

- Physical and pelvic exam.

- CA-125 blood test, especially helpful if initial results were high. (Falling CA-125 levels indicate treatment was effective and rising levels suggest disease progression).

- Imaging tests, such as a chest x-ray and CT, MRI, or PET scan of your chest, abdominal, and pelvic areas.

- Genetic counseling if needed. It is currently recommended that all women with ovarian cancer undergo BRCA testing.

Discuss with your cancer team how often you will need these tests. Some guidelines recommend follow-up visits:

- Every 2 to 4 months for the first 2 years and then

- Every 3 to 6 months for the next 3 years and then

- Once a year

You will usually have a CA-125 blood test at every visit. Your oncologist may also recommend imaging tests.

Surgery

Surgery for ovarian cancer is used for both diagnostic and treatment purposes. Surgery has two goals:

Staging.

The cancer to see if the disease is confined to the ovary or has spread to adjacent or distant regions.Debulking.

The tumor to remove as much of the cancerous tissue as possible.

It is extremely important that staging and debulking be performed by an experienced surgeon trained in cancer surgery techniques (usually a gynecologic oncologist). Accurate staging is essential for determining treatment options. Successful debulking will reduce the likelihood of repeat surgeries and increase the odds for survival.

Surgical Staging

Surgical staging involves taking biopsies (tissue samples) of:

- Ovaries, fallopian tubes, and uterus

- Lymph nodes

- Omentum (a layer of fatty tissue in the abdomen)

- Diaphragm surface

- Any areas that appear suspicious

An abdominal wash is performed by injecting a salt solution into the abdominal cavity to collect a fluid sample. The tissue and fluid samples are sent to a laboratory for evaluation. If immediate information is required, the pathologist may perform a frozen section of one of the tissue samples with a preliminary diagnosis available in 20 minutes.

The entire affected ovary is usually removed (oophorectomy) during surgical staging if the surgeon believes it might be cancerous. The surgeon will also examine the pelvic region, including the bowel and bladder, for signs of cancer invasion. If it appears the cancer has spread, the surgeon will remove the suspected cancer tissue (debulking).

Debulking

Debulking, also called surgical cytoreduction, involves removing as much of the cancer as possible. The goal is to leave behind no tumor larger than 1 centimeter and preferably to leave behind no clearly visible tumor.

The surgery is typically performed as follows:

- In premenopausal women in a very early stage of ovarian cancer who want to preserve fertility, the surgeon may be able to remove only the affected ovary and its accompanying fallopian tube. However, most women with ovarian cancer are not candidates for this procedure.

- In premenopausal women in later stages of ovarian cancer, and in all postmenopausal women, the surgeon usually removes the uterus (hysterectomy) and both ovaries and fallopian tubes (bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy). In addition, the surgeon may remove the omentum (omentectomy), and pelvic lymph nodes (lymphadenectomy).

- If the tumor has spread beyond the reproductive organs, the surgeon may need to remove parts of the colon, small bowel, appendix, bladder, spleen, stomach, or liver. If part of the colon is removed, a surgical procedure called colostomy may be performed to create a temporary opening to allow waste excretion, although in general the colon can be reconstructed to avoid a colostomy.

- If cancer persists or recurs after debulking, a second debulking surgery may be considered.

Side Effects

Hysterectomy results in infertility. A woman will no longer have menstrual periods and she can no longer become pregnant. Surgical removal of the ovaries (oophorectomy) causes immediate menopause. Symptoms, such as hot flashes, come on abruptly and may be more intense than those of natural menopause. Other menopausal symptoms include vaginal dryness, sleep problems, and weight gain.

The most important complications that occur in women who have had their ovaries removed are due to estrogen loss, which places women at risk for osteoporosis (loss of bone density) and a possible increase in risks for heart disease.

Hormone therapy after a hysterectomy is given as estrogen-only therapy (ET). It does have risks, including possibly increasing the chances for breast cancer and stroke. (Some recent data question these risks for women who do not receive estrogen in combination with progesterone.) It does not appear to increase the risk for ovarian cancer recurrence.

The decision to use estrogen therapy (ET) depends in part on a woman's age as well as other medical factors. For younger women (under age 40), the benefits of ET for bone health, sexual function, and hot flash symptoms may outweigh the risks. For women closer to the age of menopause, risks may outweigh benefits. Discuss with your oncologist whether hormone therapy is a safe or appropriate option for you.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is drug therapy used to kill cancer cells that remain after surgery. Chemotherapy usually follows surgery (adjuvant chemotherapy). In some cases, it may also be used before surgery (neoadjuvant chemotherapy).

Chemotherapy is a systemic therapy. It uses drugs that are delivered into the bloodstream to reach and destroy cancer cells throughout the body.

Chemotherapy for ovarian cancer is administered:

- Intravenously (IV) by injection into a vein.

- Intraperitoneally (IP) by injection through a catheter implanted in the abdominal cavity.

Most women with stage I, II, and IV ovarian cancer receive intravenous chemotherapy. Women in stage III may receive a combination of intravenous and intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Side effects are more severe with intraperitoneal chemotherapy than when intravenous chemotherapy is used alone. However, the combination therapy may be more effective for women with later-stage cancer.

Clinical trials investigating new drugs and combinations of drugs are available for all stages of ovarian cancer. Discuss with your oncologist whether you may be an appropriate candidate for a clinical trial.

Drugs Used in Chemotherapy

Initial chemotherapy

regimens commonly use a combination of:- Intravenous (IV) infusion, paclitaxel and carboplatin. Docetaxel with carboplatin is an alternative regimen.

- Intraperitoneal (IP) infusion, paclitaxel and cisplatin.

Paclitaxel and docetaxel are taxane drugs. Carboplatin and cisplatin are platinum-based drugs. Carboplatin causes fewer side effects than cisplatin, and in general is easier to administer and better tolerated.

Drug Therapy for Resistant or Recurred Cancer

Some ovarian tumors are resistant to platinum drugs. In other cases, the cancer returns (recurs) after treatment. There are many different drug therapy approaches to treating resistant or recurrent cancer.

A different platinum chemotherapy drug, a new type of drug, or different combinations of drugs may be tried. Some of these drugs include gemcitabine, doxorubicin, and topotecan.

Bevacizumab (Avastin) is a biologic drug used in targeted therapy. It blocks a protein that helps blood vessels form. By targeting this protein, the drug slows the growth of cancer cells. Bevacizumab is approved to treat platinum-resistant or recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. It is given by IV in combination with paclitaxel, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (Doxyl), or topotecan.

Hormone therapy may be an option for women with recurrent cancer who cannot tolerate or who have not been helped by chemotherapy. Hormone therapy drugs include:

- Tamoxifen (Nolvadex, generic)

- Letrozole (Femara, generic)

- Anastrozole (Arimidex, generic)

- Leuprolide acetate (Lupron Depot)

- Megestrol acetate (Megace)

Some of these drugs are given by injection; others are taken orally as a pill.

Recently, the FDA approved several drugs from a new class called PARP inhibitors for patients with BRCA-mutated ovarian cancer. These drugs work by blocking an enzyme called PARP, which is used by normal and cancerous cells to repair damage to their DNA that may occur during cell division. As cancer cells divide much faster than normal cells, PARP inhibitors preferentially attack cancer cells and induce their death. PARP inhibitors approved for ovarian cancer include rucaparib (Rubraca), niraparib (Zejula), and olaparib (Lynparza). PARP inhibitors are given after platinum-based chemotherapy as a maintenance therapy or as single agent therapy when patients have recurred.

Clinical Trials

Chemotherapy drugs go through a long testing process to see if they are active against various cancers and whether they are safe to use in humans. These tests are called clinical trials. When there is no well accepted treatment plan for a patient, she may be considered for a clinical trial where she may receive an experimental drug or treatment that is thought to be beneficial in fighting her cancer, but is still undergoing testing and evaluation. A good resource to find possible clinical trials for ovarian cancer as well as all others, is www.clinicaltrials.gov.

Administration of Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy drugs are given in cycles. You will receive an infusion of the drugs over the course of several days, followed by a rest period of several weeks, and then another cycle of infusion. The treatment is given in an outpatient clinic.

A chemotherapy infusion usually lasts about 3 to 6 hours. Treatment may be repeated every 3 weeks for a total of 6 cycles. Other dose schedules may require weekly treatment. The exact length of cycles varies depending on which drugs are used.

Side Effects of Chemotherapy

Side effects occur with all drugs and vary depending on the drug used. Side effects are more severe with higher doses and increase over the course of treatment. Most side effects go away after treatment is completed, but some may be long-lasting.

Common side effects may include:

- Nausea and vomiting

- Loss of appetite and weight

- Hair loss

- Mouth sores

- Fatigue

- Depression

Serious side effects may include:

- Severe drop in white blood cell count (neutropenia), which can increase the risk for infections

- Reduction of blood platelets (thrombocytopenia), which can lead to bruising or severe bleeding

- Reduction in red blood cell count (anemia), which can cause shortness of breath and fatigue

- Nerve damage (neuropathy), which cause sensations of numbness or tingling in the hands and feet

- Kidney (renal) damage, which in rare cases can be permanent

- Hearing loss which is rare but may be seen with platinum treatments

Some side effects can sometimes be treated or prevented with other drugs or non-drug therapies. For example, yoga and acupuncture may be helpful for easing fatigue. Most patients receive premedication with anti-nausea to minimize that side effect. Discuss with your cancer care team strategies to help you cope.

Cancer support groups can help ease the stress of illness. Sharing with others who have common experiences and problems can help you not feel alone.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy is not typically used as a primary treatment for ovarian cancer. Radiation is sometimes used as palliative treatment to help ease symptoms in recurrent ovarian cancer.

Resources

- National Cancer Institute -- www.cancer.gov

- American Cancer Society -- www.cancer.org

- American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) - Cancer.Net -- www.cancer.net

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network -- www.nccn.org

- Ovarian Cancer Research Alliance -- ocrahope.org

- Society of Gynecologic Oncologists -- www.sgo.org

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer -- www.cdc.gov/genomics/disease/breast_ovarian_cancer/index.htm

- Find clinical trials -- www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/clinical-trials

References

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecologic Practice. Committee Opinion No. 477: the role of the obstetrician-gynecologist in the early detection of epithelial ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(3):742-746. PMID: 21343791 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21343791.

Coleman RL, Liu J, Matsuo K, Thaker PH, Westin SN, Sood AK. Carcinoma of the ovaries and fallopian tubes. In: Niederhuber JE, Armitage JO, Kastan MB, Doroshow JH, Tepper JE, eds. Abeloff's Clinical Oncology. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 86.

Coleman RL, Ramirez PT, Gershenson DM. Neoplastic diseases of the ovary: screening, benign and malignant epithelial and germ cell neoplasms, sex-cord stromal tumors. In: Lobo RA, Gershenson DM, Lentz GM, Valea FA, eds. Comprehensive Gynecology. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017:chap 33.

Cortez AJ, Tudrej P, Kujawa KA, Lisowska KM. Advances in ovarian cancer therapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2018;81(1):17-38. PMID: 29249039 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29249039.

Doubeni CA, Doubeni AR, Myers AE. Diagnosis and management of ovarian cancer. Am Fam Physician. 2016;93(11):937-944. PMID: 27281838 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27281838.

Finch AP, Lubinski J, Møller P, et al. Impact of oophorectomy on cancer incidence and mortality in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15):1547-1553. PMID: 24567435 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24567435.

Henderson JT, Webber EM, Sawaya GF. Screening for ovarian cancer: Updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;319(6):595-606. PMID: 29450530 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29450530.

Lheureux S, Gourley C, Vergote I, Oza AM. Epithelial ovarian cancer. Lancet. 2019;393(10177):1240-1253. PMID: 30910306 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30910306.

Loren AW, Mangu PB, Beck LN, et al. Fertility preservation for patients with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(19):2500-2510. PMID: 23715580 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23715580.

Mavaddat N, Peock S, Frost D, et al. Cancer risks for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: results from prospective analysis of EMBRACE. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(11):812-822. PMID: 23628597 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23628597.

Moyer VA; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Risk assessment, genetic counseling, and genetic testing for BRCA-related cancer in women: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(4):271-281. PMID: 24366376 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24366376.

National Cancer Institute website. Ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancer prevention (PDQ) - health professional version. www.cancer.gov/types/ovarian/hp/ovarian-prevention-pdq. Updated December 13, 2019. Accessed December 27, 2019.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network website. Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast and Ovarian.Version 3.2019. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/genetics_screening.pdf. Updated January 18, 2019. Accessed June 20, 2019.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network website. Ovarian cancer including fallopian tube cancer and primary peritoneal cancer.Version 1.2019. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/ovarian.pdf. Updated March 8, 2019. Accessed June 20, 2019.

Neff RT, Senter L, Salani R. BRCA mutation in ovarian cancer: testing, implications and treatment considerations. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2017;9(8):519-531. PMID: 28794804 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28794804.

Torre LA, Trabert B, DeSantis CE, et al. Ovarian cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(4):284-296. PMID: 29809280 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29809280.

|

Review Date:

8/26/2019 Reviewed By: Howard Goodman, MD, Gynecologic Oncology, Florida Cancer Specialists & Research Institute, West Palm Beach, FL. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team. |