Gastroesophageal reflux disease and heartburn - InDepth

Highlights

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a condition in which gastric contents and acid flow up from the stomach into the esophagus (food pipe) due to poor stomach emptying, poor valve function, and problems with the esophagus.

Frequent and mild gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is quite common, especially in infants, but the disease (GERD) is more severe and causes complications.

It is estimated that about half of American adults experience GERD symptoms at least once a month.

The hallmark symptoms of GERD may occur several times per day and include:

- Heartburn. A burning sensation in the chest and throat.

- Regurgitation. A sensation of acid or food/liquid backed up in the esophagus.

Typical GERD symptoms in infants include frequent regurgitation, irritability, arching the back, choking or gagging, and resisting feedings.

- Dysfunction of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) is the most common cause of GERD. LES is the band of muscle tissue that is essential for maintaining a pressure barrier against backflow of contents from the stomach. If it weakens and loses tone, the LES cannot close completely, and acid from the stomach backs up into the esophagus. The cause can be structural, but diet and other factors can also interfere with LES function and trigger GERD.

- Problems in the esophagus and the stomach's ability to empty may also cause GERD.

- Early diagnosis and treatment is best in order to avoid complications such as changes in the esophagus that can lead to cancer.

- A combination of tests is often needed to confirm the diagnosis.

- Upper endoscopy is recommended for people with severe GERD symptoms, for adults who have had an unsuccessful trial of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) for GERD, and for men over 50 with chronic GERD symptoms and other risk factors.

- Certain people will require ongoing monitoring and examinations every 3 to 5 years or sooner.

- Long-term use of PPIs has been linked to an increased risk of hip, wrist, and spine fractures. Cardiac events, drug-drug interactions, iron deficiency, low magnesium levels, and gastrointestinal infection are also concerns with long term use of PPIs.

- Studies have found that taking the PPI omeprazole with the blood thinner clopidogrel (Plavix) reduces the effectiveness of this blood thinner by nearly 50%. People should avoid taking omeprazole with Plavix and may consider pantoprazole (Protonix) instead.

- A warning added in May 2012 cautions that using certain PPIs with methotrexate, a drug commonly used to treat certain cancers and autoimmune conditions, can lead to elevated levels of methotrexate in the blood, causing toxic side effects.

Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a condition in which acid from the stomach flows back up into the esophagus (the food pipe), a situation called reflux. Reflux occurs if the muscular actions of the lower esophagus or other protective mechanisms fail.

The hallmark symptoms of GERD are:

- Heartburn. A burning sensation in the chest and throat.

- Regurgitation. A sensation of acid or food/liquid backed up in the esophagus.

Although acid is a primary factor in damage caused by GERD, other products of the digestive tract, including pepsin and bile, can also be harmful.

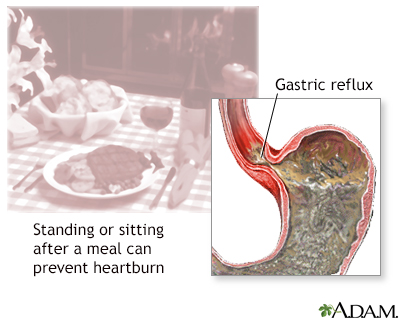

Heartburn is a condition in which the acidic stomach contents back up into the esophagus, causing pain in the chest area. This reflux usually occurs because the sphincter muscle between the esophagus and stomach is weakened. Remaining upright by standing or sitting up after eating a meal can help reduce the reflux that causes heartburn. Continuous irritation of the esophagus lining, as in severe GERD, is a risk factor for developing esophageal cancer.

The esophagus, commonly called the food pipe, is a narrow muscular tube about 9.5 inches (25 centimeters) long. It begins below the tongue and ends at the stomach. The esophagus is narrowest at the top and bottom; it also narrows slightly in the middle.

The esophagus wall consists of 3 basic layers:

- An outer layer of fibrous tissue

- A middle layer containing smoother muscle

- An inner membrane, which contains many tiny glands

When a person swallows food, the esophagus moves it into the stomach through the action of wave-like muscle contractions, called peristalsis. In the stomach, acid and various enzymes break down the starch, fat, and protein in food. The lining of the stomach has a thin layer of mucus that protects it from these fluids.

However, if acid and enzymes back up into the esophagus, its lining offers only a weak defense against these substances. Instead, several other factors protect the esophagus. The most important structure protecting the esophagus may be the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). The LES is a band of muscle around the bottom of the esophagus, where it meets the stomach.

- After a person swallows, the LES opens to let food enter the stomach. It then closes immediately to prevent regurgitation (backward flow) of the stomach's contents, including gastric acid.

- The LES maintains this pressure barrier until food is swallowed again.

If the pressure barrier is not enough to prevent regurgitation and acid backs up (reflux), peristaltic action of the esophagus serves as an additional defense mechanism, pushing the backed-up contents back down into the stomach.

Causes

Anyone who eats a lot of acidic foods can have mild and temporary reflux. This is especially true when lifting, bending over, or lying down after eating a large meal high in fatty, acidic foods. However, persistent GERD may be due to various conditions, including biological or structural problems.

The band of muscle tissue called the LES is responsible for closing and opening the lower end of the esophagus, and is essential for maintaining a pressure barrier against contents from the stomach. For it to function properly, there needs to be interaction between smooth muscles and various hormones. If it weakens and loses tone, the LES cannot close completely after food empties into the stomach, and acid from the stomach backs up into the esophagus. Dietary substances, drugs, and nervous system factors can weaken the LES and impair its function.

People with GERD may have abnormal nerve or muscle function in the stomach. These abnormalities prevent the stomach muscles from contracting normally, which causes delays in stomach emptying, and increasing the risk for acid back-up.

Some studies suggest that most people with atypical GERD symptoms (such as hoarseness, chronic cough, or the feeling of having a lump in the throat) have specific abnormalities in the esophagus.

Motility Abnormalities

Problems in spontaneous muscle action (peristalsis) in the esophagus commonly occur in GERD, although it is not clear whether such problems cause the condition, or are the result of long-term GERD.

Adult-Ringed Esophagus

People with this condition have many rings (constrictions or narrowing) on the esophagus and persistent trouble swallowing (including getting food stuck in the esophagus). Adult-ringed esophagus occurs mostly in men. The causes of this condition are unclear.

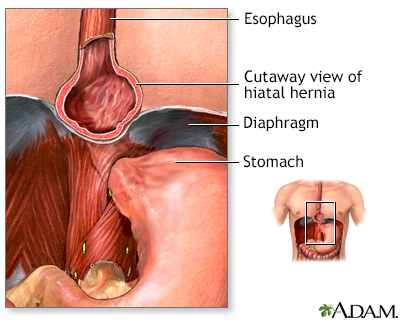

The hiatus is a small opening in the diaphragm (the muscle that separates the chest cavity from the abdominal cavity) through which the esophagus passes into the abdomen, where it is continued with the stomach. The hiatus is normally small and tight, but it may weaken and enlarge. When this happens, part of the stomach muscles may protrude into it, producing a condition called hiatal hernia. It is very common, occurring in more than half of people over 60 years old, and is rarely serious. It was once believed that most cases of persistent heartburn were caused by a hiatal hernia. Indeed, a hiatal hernia may impair LES muscle function. However, studies have failed to confirm that it is a common cause of GERD, although its presence may increase GERD symptoms in patients who have both conditions.

A hiatal hernia occurs when part of the stomach protrudes up into the chest through the sheet of muscle called the diaphragm. This may result from a weakening of the surrounding tissues and may be aggravated by obesity or smoking.

About 30% to 40% of reflux is most likely hereditary, according to several twin and family studies. An inherited risk exists in many cases of GERD, possibly because of inherited muscular or structural problems in the stomach or esophagus. Genetic factors may play an especially strong role in susceptibility to Barrett esophagus, a precancerous condition caused by very severe GERD.

Crohn disease is a chronic ailment that causes inflammation and injury in the small intestine, colon, and other parts of the gastrointestinal tract, sometimes including the esophagus. Other disorders that may contribute to GERD include diabetes, any gastrointestinal disorder (including peptic ulcers), lymphomas, and other types of cancer.

Helicobacter pylori, also called H pylori, is a bacterium that is sometimes found in the mucus membranes of the stomach. It is now known to be the major cause of peptic ulcers. Antibiotics that eradicate H pylori are the accepted treatment for preventing and curing ulcers.

The role of H pylori in causing GERD is less clear. It may depend on what portion of the stomach is involved. Although in some patients, treating H pylori may actually worsen symptoms, in general treating H pylori is unlikely to worsen GERD.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

NSAIDs, common causes of peptic ulcers, may also cause GERD or increase its severity in people who already have it. There are dozens of NSAIDs, including over-the-counter aspirin, ibuprofen (Motrin, Advil, Nuprin), and naproxen (Aleve), as well as prescription anti-inflammatory medicines. People with GERD who take the occasional aspirin or other NSAID will not necessarily experience adverse effects, especially if they have no risk factors or evidence of ulcers. Acetaminophen (Tylenol), which is not an NSAID, is a good alternative for those who want to relieve mild pain without increasing GERD risk. However, Tylenol does not relieve inflammation.

Other Drugs

Many other drugs can increase the risk for GERD, including:

- Calcium channel blockers (used to treat high blood pressure and angina)

- Anticholinergics (used to treat urinary tract disorders, allergies, and glaucoma)

- Beta-adrenergic agonists (used to treat asthma and obstructive lung diseases)

- Dopamine agonists (used in Parkinson disease)

- Bisphosphonates (used to treat osteoporosis)

- Sedatives

- Antibiotics

- Potassium

- Iron pills

Risk Factors

About half of American adults experience GERD symptomsat least once a month. People of all ages are susceptible to GERD. Elderly people with GERD tend to have a more serious condition than younger people.

Eating Patterns

People who eat a heavy meal and then lie on their back or bend over from the waist are at risk for an attack of heartburn. Anyone who snacks at bedtime is also at high risk for heartburn.

Pregnancy

Pregnant women are particularly vulnerable to GERD in their third trimester, as the growing uterus puts increasing pressure on the stomach. Heartburn, in such cases, is often resistant to dietary interventions and even to antacids.

Obesity

A number of studies suggest that obesity contributes to GERD, and it may increase the risk for severe inflammation in the esophagus in people with GERD. Having excess abdominal fat may be the most important risk factor for the development of acid reflux and associated complications, such as Barrett esophagus and cancer of the esophagus. Losing weight appears to help reduce GERD symptoms.

Respiratory Diseases

People with asthma are at very high risk for GERD. About 50% to 90% of people with asthma have some symptoms of GERD. People with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are also at increased risk for GERD, and having GERD may worsen pre-existing COPD.

Smoking

Increasing evidence indicates that smoking raises the risk for GERD. Smoking reduces LES muscle function, increases acid secretion, impairs muscle reflexes in the throat, and damages protective mucus membranes. Smoking reduces salivation, and saliva helps neutralize acid. It is unknown whether the smoke, nicotine, or both trigger GERD. For example, some people who use nicotine patches to quit smoking have heartburn, but it is not clear whether the nicotine or stress produces the acid backup. In addition, smoking can lead to emphysema, a form of COPD, which is itself a risk factor for GERD.

Alcohol Use

Alcohol has mixed effects on GERD. It relaxes the LES muscles and, in high amounts, may irritate the mucus membrane of the esophagus. Small amounts of alcohol, however, may actually protect the mucosal layer.

It should be noted that a combination of heavy alcohol use and smoking increases the risk for esophageal cancer.

Hormone Replacement Therapy

Symptoms of GERD are more likely to occur in postmenopausal women who receive hormone replacement therapy. The risk increases with larger estrogen doses and longer duration of therapy.

Symptoms

Heartburn

Heartburn is the primary symptom of GERD. It is a burning sensation that spreads up from the stomach to the chest and throat. Heartburn is most likely to occur in connection with the following activities:

- Eating a heavy or big meal

- Bending over

- Lifting

- Lying down, particularly on the back

People with nighttime GERD, a common problem, tend to feel more severe pain than those whose symptoms occur at other times of the day.

The severity of heartburn does not necessarily indicate actual injury to the esophagus. For example, Barrett esophagus, which causes precancerous changes in the esophagus, may only trigger a few symptoms, especially in elderly people. On the other hand, people can have severe heartburn but suffer no damage to their esophagus.

Dyspepsia

Nearly half of people with GERD have dyspepsia, a syndrome that consists of:

- Pain and discomfort in the upper abdomen

- A feeling of fullness in the stomach

- Nausea after eating

People without GERD can also have dyspepsia.

Regurgitation

Regurgitation is the feeling of acid backing up in the throat. Sometimes acid regurgitates as far as the mouth and can be experienced as a "wet burp." Uncommonly, it may come out forcefully as vomit.

Many people with GERD do not have heartburn or regurgitation. Older people with GERD often have less typical symptoms than younger people. Instead, symptoms may occur in the mouth or lungs.

Chest Sensations or Pain

People may have the sensation that food is trapped behind the breastbone. Chest pain is a common symptom of GERD. It is very important to differentiate it from chest pain caused by heart conditions, such as angina and heart attack.

Symptoms in the Throat

Less commonly, GERD may produce symptoms that occur in the throat, including:

- Acid laryngitis. A condition that includes hoarseness, dry cough, the sensation of having a lump in the throat, and the need to repeatedly clear the throat.

- Trouble swallowing (dysphagia). In severe cases, people may choke or food may become trapped in the esophagus, causing severe chest pain. This may indicate a temporary spasm that narrows the tube, or it could indicate serious esophageal damage or abnormalities.

- Chronic sore throat.

- Persistent hiccups.

Coughing and Respiratory Symptoms

Airway symptoms, such as coughing and wheezing, may occur.

Chronic Nausea and Vomiting

Nausea that persists for weeks or even months, and is not traced back to a common cause of stomach upset, may be a symptom of acid reflux. In rare cases, vomiting can occur as often as once a day. All other causes of chronic nausea and vomiting should be ruled out, including ulcers, stomach cancer, obstruction, and pancreas or gallbladder disorders.

GER is very common in children of all ages, but it is usually mild. Symptoms usually get better in most infants by age 12 months, and in nearly all children by 24 months. Children with the following conditions are at higher risk for true GERD:

- Brain injury and impairments

- Food allergies

- Scoliosis

- Cyclic vomiting

- Cystic fibrosis

- Problems in the lungs, ear, nose, or throat

- Any medical condition affecting the digestive tract

Symptoms in Children

Typical reflux symptoms in infants include:

- Frequent regurgitation

- Irritability

- Arching the back

- Choking or gagging

- Resisting feedings

A physician should examine any child who has symptoms of severe GERD as soon as possible, because these symptoms may lead to complications such as anemia, failure to gain weight, or respiratory problems. Symptoms of severe GERD in infants and small children may include:

- Poor weight gain.

- Refusing feedings.

- Chronic coughing.

- Frequent infections.

- Irritability.

- Wheezing.

- Breathing or sleeping difficulties, such as gasping or frequently stopping breathing while asleep (a condition called sleep apnea).

- Severe vomiting, particularly if it is green colored (bilious), always requires a doctor's visit, because it could be a symptom of a severe obstruction.

These symptoms may be related to other causes. Babies and children may experience these symptoms without having GERD.

In addition, many infants with normal irritability are being inappropriately treated for reflux disorders.

Complications

Nearly everyone has an attack of heartburn at some point in their lives. In the vast majority of cases, the condition is temporary and mild, causing only short-term discomfort. If people develop persistent GERD with frequent relapses, and it remains untreated, serious complications may develop over time. Complications can include:

- Erosive esophagitis

- Severe narrowing (stricture) of the esophagus

- Barrett esophagus, a condition associated with increased risk for esophageal cancer

- Problems in other areas, including the teeth, throat, and airways leading to the lungs

Older people are at higher risk for complications from persistent GERD. The following conditions also put individuals at risk for recurrent and serious GERD:

- Very inflamed esophagus

- Severe symptoms

- Symptoms that continue in spite of treatments to heal the esophagus

- Severe muscle abnormalities

Despite the complications that can occur with the condition, GERD does not appear to shorten life expectancy.

Erosive esophagitis develops in people with chronic GERD when acid irritation and inflammation cause extensive injuries to the esophagus. The longer and more severe the GERD, the higher the risk for developing erosive esophagitis.

Bleeding may occur in about 8% of people with erosive esophagitis. In very severe cases, people may have dark-colored, tarry stools (indicating the presence of blood) or may vomit blood, particularly if ulcers have developed in the esophagus. This is a sign of severe damage and requires immediate attention.

Sometimes long-term bleeding can result in iron-deficiency anemia and may even require emergency blood transfusions. This condition can occur without heartburn or other warning symptoms, or even without obvious blood in the stools.

Barrett esophagus is a disorder in which the lining of the esophagus is damaged by stomach acid. The lining becomes similar to that of the stomach. These changes place a person at risk for esophageal cancer.

Only 10% of people with symptomatic GERD have Barrett esophagus. While obesity, alcohol use, and smoking have all been implicated as risk factors for Barrett esophagus, their role remains unclear. Only the persistence of GERD symptoms indicates a higher risk for Barrett esophagus.

Not all people with Barrett esophagus have esophagitis or symptoms of GERD. More than half of people with the condition have no GERD symptoms at all. Barrett esophagus, then, is likely to be much more common and probably less harmful than is currently believed.

The incidence of esophageal cancer is higher in people with Barrett esophagus. When people with Barrett esophagus develop abnormal changes of the mucous membrane cells lining the esophagus (dysplasia), the risk of cancer rises significantly. There is some evidence that acid reflux may contribute to the development of cancer in Barrett esophagus. Still, only a minority of people with Barrett esophagus develop cancer.

Some experts recommend that people with Barrett esophagus who also have other risk factors for esophageal cancer undergo endoscopic screening every 3 to 5 years. Destroying any abnormal cells (dysplasia) with heat, cold, laser, or other methods is the treatment of choice.

Complications of Strictures

If the esophagus becomes severely injured over time, narrowed regions called strictures can develop, which may impair swallowing (a condition known as dysphagia). Stretching procedures or surgery may be required to restore normal swallowing. Strictures may actually prevent other GERD symptoms, by stopping acid from traveling up the esophagus.

Asthma

Asthma and GERD often occur together. Some theories about the connection between GERD and asthma are:

- Small amounts of stomach acid backing up into the esophagus can lead to changes in the immune system, and these changes trigger asthma.

- Acid leaking from the lower esophagus stimulates the vagus nerves, which run through the gastrointestinal tract. These stimulated nerves cause the nearby airways in the lung to constrict, producing asthma symptoms.

- Acid backup that reaches the mouth may be inhaled (aspirated) into the airways. Here, the acid triggers a reaction in the airways that causes asthma symptoms.

There is some evidence that asthma triggers GERD, but in people who have both conditions, treating GERD does not appear to improve asthma.

Other Respiratory and Airway Conditions

Studies indicate an association between GERD and various upper respiratory problems that occur in the sinuses, ear and nasal passages, and airways of the lung. People with GERD appear to have an above-average risk for chronic bronchitis, chronic sinusitis, emphysema, pulmonary fibrosis (lung scarring), and recurrent pneumonia. If a person inhales fluid from the esophagus into the lungs, serious pneumonia can occur. It is not yet known whether treating GERD would also reduce the risk for these respiratory conditions.

Dental erosion (the loss of the tooth's enamel coating) is a potential problem among people with GERD, including children. It results from acid backing up into the mouth and wearing away the tooth enamel.

An estimated 20% to 60% of people with GERD have symptoms in the throat (hoarseness, sore throat) without any significant heartburn. A failure to diagnose and treat GERD may lead to persistent throat conditions, such as chronic laryngitis, hoarseness, difficulty speaking, sore throat, cough, constant throat clearing, and granulomas (soft, pink bumps) on the vocal cords.

GERD commonly occurs with obstructive sleep apnea, a condition in which breathing stops temporarily many times during sleep. Sleep apnea may develop in infants, children, or adults with GERD. It is not clear which condition is responsible for the other, but GERD is particularly severe when it occurs together with sleep apnea. In adults, the two conditions may have risk factors in common, such as obesity and sleeping on the back. Studies suggest that in adults with sleep apnea, GERD can be markedly improved with a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) device, which opens the airways and is the standard treatment for severe sleep apnea.

Feeding Problems

Children with GERD tend to refuse food and may be late in eating solid foods.

Associations with Asthma and Infections in the Upper Airways

In addition to asthma, GERD is associated with other upper airway problems, including ear infections and sinusitis.

Sleeping difficulties

Infants and children with GERD are at higher risk for sleep apnea.

Rare Complications in Infants with GERD

The following complications only occur in rare cases:

- Failure to thrive

- Anemia resulting from feeding problems and severe vomiting

- Acid backup that is inhaled into the airways and causes pneumonia

The infant's life may be in danger if acid reflux causes spasms in the larynx severe enough to block the airways. Some experts believe this chain of events may contribute to sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). More research is needed to determine whether this association is valid.

Diagnosis

A person with chronic heartburn is likely to have GERD. (Occasional heartburn does not necessarily indicate the presence of GERD.) The following is the general way to diagnose GERD:

- A physician can usually diagnose GERD if the person finds relief from persistent heartburn and acid regurgitation after taking antacids for short periods of time.

- If the diagnosis is uncertain, but the physician still suspects GERD, a drug trial using a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) medication, such as omeprazole (Prilosec, generic), identifies 80% to 90% of people with the condition. This class of medication decreases stomach acid secretion.

Laboratory or more invasive tests, including endoscopy, may be required if:

- The diagnosis is still uncertain

- Symptoms are not typical

- Barrett esophagus is suspected

- Complications are present, such as signs of bleeding or difficulty swallowing

Some of these tests are described below.

A barium swallow radiograph (x-ray) is useful for identifying structural abnormalities and erosive esophagitis. For this test, the patient drinks a solution containing barium, and then x-rays of the digestive tract are taken. This test can show strictures, active ulcer craters, hiatal hernia, erosions, or other abnormalities. However, it cannot reveal mild irritation.

Upper endoscopy, also called esophagogastroduodenoscopy or panendoscopy, is more accurate than a barium swallow radiograph. It is also more invasive and expensive. It is widely used in GERD for identifying and grading severe esophagitis, monitoring people with Barrett esophagus, or when other complications of GERD are suspected. Upper endoscopy is also used as part of various surgical techniques.

Guidelines from the American Gastroenterological Association do not recommend endoscopy screening for everyone with chronic GERD because there is no evidence that it can improve survival rates for cancer.

The American College of Physicians recommends upper endoscopy in:

- Men and women with severe heartburn, difficulty or painful swallowing, and other severe GERD symptoms.

- Adults who have had an unsuccessful 4 to 8 week trial of PPI for GERD.

- Men over age 50 with chronic GERD symptoms for more than 5 years and other risk factors, such as smoking or obesity.

- People with Barrett esophagus every 3 to 5 years, or more frequently if abnormal cells are found.

The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy recommends that patients diagnosed with GERD have endoscopy if they have:

- GERD symptoms that persist or progress despite appropriate treatment.

- Difficulty or painful swallowing.

- Persistent vomiting (7 to 10 days).

- Evidence of GI bleeding or anemia.

- Unintentional weight loss of more than 5% body weight.

- An ulcer, stricture, or mass detected with imaging studies.

- Additional indications include Barrett esophagus screening, pre- or post- antireflux surgical procedures, and placing pH monitors.

Endoscopy to Diagnose GERD

Endoscopy may be performed either in a hospital or doctor's office:

- The person should eat nothing for at least 6 hours before the procedure.

- The doctor administers a local anesthetic using an oral spray and an intravenous sedative to suppress the gag reflex and relax the person.

- Next, the physician places an endoscope (a thin, flexible fiberoptic tube containing a tiny camera) into the person's mouth and down the esophagus. The procedure does not interfere with breathing. It may be slightly uncomfortable for some people; others are able to sleep through it.

- Once the endoscope is in place, the camera allows the physician to see the surface of the esophagus and look for abnormalities, including hiatal hernia and damage to the mucus lining.

- The physician may perform a biopsy (the removal and microscopic examination of small tissue sections). The biopsy may detect tissue injury from GERD. It may also be used to detect cancer or other conditions, such as yeast (Candida albicans) or viral infections (such as herpes simplex and cytomegalovirus). Such infections are more likely to occur in people with impaired immune systems.

Complications from the procedure are uncommon. If they occur, complications are usually mild and typically include minor bleeding from the biopsy site or irritation where medications were injected.

If a person has moderate-to-severe GERD symptoms and the procedure reveals injury in the esophagus, usually no further tests are needed to confirm a diagnosis. The test is not foolproof, however. A visual view misses about half of all esophageal abnormalities.

Capsule Endoscopy

In this test, the person swallows a small capsule containing a tiny camera. Then, a series of color pictures are transmitted to a recording device where they can be downloaded and interpreted by a doctor. The entire procedure takes 20 minutes. The capsule is naturally passed through the digestive system within 24 hours. A newer technique has a string attached to the capsule for retrieval. Capsule endoscopy may provide a less invasive alternative to traditional endoscopy. However, while capsule endoscopy is useful as a screening device for diagnosing esophageal conditions such as GERD and Barrett esophagus, traditional endoscopy is still required for obtaining tissue samples.

Barrett esophagus is diagnosed using endoscopy.

Monitoring People with Barrett Esophagus for Cancer

Periodic endoscopy is recommended for detecting cancer at an earlier stage in people who have been diagnosed with Barrett esophagus. When Barrett esophagus is diagnosed, multiple biopsies are generally taken. The biopsy results will determine the frequency of future monitoring. Unfortunately, monitoring people with Barrett esophagus has not been proven to change overall mortality rates from esophageal cancer.

The (ambulatory) pH monitor examination may be used to determine acid backup. It is useful when endoscopy has not detected damage to the mucus lining in the esophagus, but GERD symptoms are present. pH monitoring may be used when people have not found relief from medicine or surgery. Traditional trans-nasal catheter diagnostic procedures involved inserting a tube through the nose and down to the esophagus. The tube was left in place for 24 hours. This test was irritating to the throat, and uncomfortable and awkward for most patients.

Another method uses a small capsule-sized data transmitter that is temporarily attached to the wall of the esophagus during endoscopy. The capsule records pH levels and transmits these data to a pager-sized receiver the person wears. People can maintain their usual diet and activity schedule during the 24 to 48-hour monitoring period. After a few days, the capsule detaches from the esophagus, passes through the digestive tract, and is eliminated through a bowel movement.

Manometry is a technique that measures muscular pressure. It uses a tube containing various openings, which is placed through the esophagus. As the muscular action of the esophagus puts pressure on the tube in various locations, a computer connected to the tube measures this pressure. Manometry is useful for the following situations:

- To determine whether a person with GERD would benefit from surgery, by measuring pressure exerted by the lower esophageal sphincter muscles.

- To detect impaired stomach motility (an inability of the muscles to contract normally) that cannot be surgically corrected with standard procedures.

- To determine whether impaired peristalsis or other motor abnormalities are causing chest pain in people with GERD.

Blood and Stool Tests

Stool tests may show traces of blood that are not visible. Blood tests for anemia should be performed if bleeding is suspected.

Bernstein Test

For people with chest pain in which the diagnosis is uncertain, a procedure called the Bernstein test may be helpful, although it is rarely used today. A tube is inserted through the patient's nasal passage. Solutions of hydrochloric acid and saline (salt water) are administered separately into the esophagus. A diagnosis of GERD is established if the acid infusion causes symptoms but the saline solution does not.

Tests in Children

Diagnostic tests are often unnecessary in children and adolescents for common GER or GERD. In the absence of more severe symptoms, a conservative approach to diagnosis and treatment is best. In addition to the tests above, other tests that may be used for diagnosis in children include gastroesophagealscintigraphy (milk scan) and esophageal impedance (EI).

Because many illnesses share similar symptoms, a careful diagnosis and consideration of the person's history is key to an accurate diagnosis. The following are only a few of the conditions that could accompany or resemble GERD:

- Dyspepsia. The most common disorder confused with GERD is dyspepsia, which is pain or discomfort in the upper abdomen without heartburn. Specific symptoms may include a feeling of fullness (particularly early in the meal), bloating, and nausea. Dyspepsia can be a symptom of GERD, but it does not always occur with GERD. Treatment with both antacids and PPI can have benefits. The drug metoclopramide (Reglan) helps stomach emptying and may be useful for this condition.

- Angina and Chest Pain. About 600,000 people come to emergency rooms each year with chest pain. More than 100,000 of these people are believed to actually have GERD. Chest pain from both GERD and severe angina can occur after a heavy meal. In general, a heart problem is less likely to be responsible for the pain if it is worse at night and does not occur after exercise- in people who are not known or at risk to have heart disease. It should be noted that the 2 conditions often coexist.

- Other Causes of Esophagitis. There are a number of other causes of esophagitis besides acid reflux. Infections such as Candida and other fungi or yeast and viruses such as herpes or cytomegalovirus may cause swollen and inflamed tissue in the esophagus. Certain pills may cause focal swelling and damage in the esophagus. Finally, a condition called eosinophilic esophagitis is an allergic or immune problem involving the esophagus. This latter problem is being diagnosed much more often recently.

- Other Diseases. Many gastrointestinal diseases (such as inflammatory bowel disease, ulcers, and intestinal cancers) can cause symptoms similar to GERD, but they can be diagnosed correctly because they produce additional symptoms and affect different areas of the intestinal tract.

Lifestyle Treatment and Prevention

People with heartburn should first try lifestyle and dietary changes. Although foods do not cause GERD, in some people certain foods may trigger symptoms. Some lifestyle suggestions are:

- Avoid or reduce consumption of foods and beverages that contain caffeine, chocolate, garlic, onions, peppermint, spearmint, and alcohol. Both caffeinated and decaffeinated coffees increase acid secretion.

- Avoid all carbonated drinks. They increase the risk for GERD.

- Choose low-fat or skim dairy products, poultry, and fish.

- Eat a diet rich in fruits and vegetables, although it is best to avoid acidic vegetables and fruits (such as oranges, lemons, grapefruit, pineapple, and tomatoes).

- People who have trouble swallowing should avoid tough meats, vegetables with skins, doughy bread, and pasta.

Nearly 75% of people with frequent GERD symptoms have them at night. People with nighttime GERD also tend to experience severe pain. It is very important to take preventive measures before going to sleep, such as:

- After meals, take a walk or stay upright.

- Avoid bedtime snacks. In general, do not eat for at least 2 hours before bedtime.

- When going to bed, try lying on the left side rather than the right side. The stomach is located higher than the esophagus when you sleep on the right side, which can put pressure on the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), increasing the risk for fluid backup.

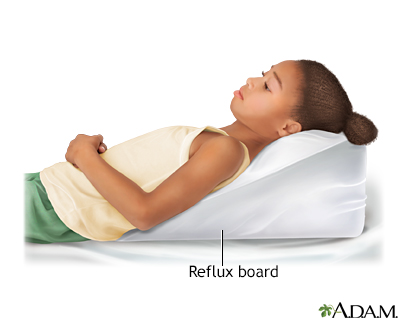

- Sleep in a tilted position to help keep acid in the stomach at night. To do this, raise the bed at an angle using 4- to 6-inch blocks at the head of the bed. Or, use a wedge-support such as a foam wedge underneath the mattress to elevate the top half of your body. (Extra pillows that only raise the head actually increase the risk for reflux.) How well this type of position change works as a treatment of GERD in older children has not been well studied.

A reflux board is a device prescribed for use in children who have GER. The board tilts the child upward, to prevent or reduce GER while the child is lying in bed.

- Quitting smoking is essential.

- People who are overweight or obese should try to diet and exercise to lose weight.

- People with GERD should avoid wearing tight clothing, particularly around the abdomen.

- If possible, people with GERD should avoid NSAIDs, such as aspirin, ibuprofen (Motrin, Advil), or naproxen (Aleve). Acetaminophen (Tylenol) is a good alternative pain reliever.

Although gum chewing is commonly believed to increase the risk for GERD symptoms, one study reported that it might be helpful. Because saliva helps neutralize acid and contains a number of other factors that protect the esophagus, chewing gum 30 minutes after a meal has been found to help relieve heartburn and even protect against damage caused by GERD. Chewing on anything can help, because it stimulates saliva production.

Treatment

Acid suppression continues to be the mainstay for treating GERD that does not respond to lifestyle changes and treatment. The aim of drug therapy is to reduce the amount of acid and improve any abnormalities in muscle function of the lower esophageal sphincter, esophagus, or stomach.

Most cases of gastroesophageal reflux (GER) are mild and can be managed with lifestyle changes, over-the-counter medications, and antacids.

People with moderate-to-severe GERD symptoms that do not respond to lifestyle changes, or who are diagnosed at a late stage may be started on medications of varying strength, depending on their complications at diagnosis. The 2 major treatment options are known as the step-up and step-down approaches:

- Step-up. With a step-up drug approach, the patient first tries an H2 blocker drug (a drug that interferes with acid production), which is available over the counter. These drugs include famotidine (Pepcid AC, generic), cimetidine (Tagamet HB, generic), and nizatidine (Axid AR, generic). If the condition fails to improve, therapy is "stepped up" to an 8-week course of a more powerful drug, like a PPI.

- Step-down. A step-down approach first uses a more potent drug, most often a PPI, such as omeprazole. When people have been symptom-free for 2 months or longer, they are then "stepped down" to a half-dose. If symptoms do not come back, the drug is stopped. If symptoms return, the person is put on high-dose H2 blockers. Some physicians argue that the step-down approach should be used for most people with moderate-to-severe GERD.

If neither approach relieves symptoms, the physician should look for other conditions. Endoscopy and other tests might be used to confirm GERD and rule out other disorders, as well as evaluate when treatment is not working. In some cases, bile, not acid, may be responsible for symptoms, so acid-reducing or blocking agents would not be helpful. Bile is a fluid that is present in the small intestine and gallbladder.

A more recent approach involves an implantable device that includes a ring of titanium magnetic beads that are placed around the lower end of the esophagus. Smaller short-term studies appeared to report a decrease in symptoms and medication usage without significant complications. The device has not been studied in a randomized trial comparing it with other therapies for GERD and its current role is not yet well-defined.

Surgery may be needed in certain circumstances, such as:

- If lifestyle changes and drug treatments have failed

- If people cannot tolerate medication

- In people who have other medical complications

- In younger people with chronic GERD, who face a lifetime of expense and inconvenience with maintenance drug treatment

Some physicians are recommending surgery as the treatment of choice for many more people with chronic GERD, particularly because minimally invasive surgical procedures are becoming more widely available, and only surgery improves regurgitation. Furthermore, persistent GERD appears to be much more serious than was previously believed, and the long-term safety of using medication for acid suppression is still uncertain.

Nonetheless, anti-GERD procedures have many complications and high failure rates. The true benefit of surgery for patients who have failed medicine therapy is controversial. As with medications, current surgical procedures cannot cure GERD. About 15 to 66% of people still require anti-GERD medications after surgery. Furthermore, about 40% of surgical patients are at risk for new symptoms after surgery (such as gas, bloating, and difficulty swallowing), with most side effects occurring more than a year after surgery. Finally, evidence now suggests that surgery does not reduce the risk for esophageal cancer in high-risk people, such as those with Barrett esophagus. New procedures may improve current results, but at this time people should consider surgical options very carefully with both a surgeon and their primary doctor.

To date, no treatments can reverse the cellular damage after Barrett esophagus has developed, although some procedures are showing promise.

Medications

If a person is diagnosed with Barrett esophagus, the doctor will prescribe PPIs to suppress acid. Using these medications may help slow the progression of abnormal changes in the esophagus.

Surgery

Surgical treatment of Barrett esophagus may be considered when patients develop high-grade dysplasia of the cells lining the esophagus. Barrett esophagus alone is not a reason to perform anti-reflux surgery, and is only recommended when other reasons for this surgery are present. See "Surgery" section.

To manage GERD in infants:

- During and after feeding, infants should be positioned vertically and burped frequently.

- Breastfeeding mothers may need to change their diet temporarily. A 2-week exclusion diet typically starts with milk and eggs to see if symptoms improve.

- If a baby with GERD is fed formula, the mother should ask the doctor how to thicken it, or change the type of formula, in order to prevent splashing up from the stomach.

- Parents of infants with GERD should discuss the baby's sleeping position with their pediatrician. The seated position should be avoided, if possible. Experts strongly recommend that all healthy infants sleep on their backs to help prevent sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). For babies with GERD, however, lying on the back may obstruct the airways. If the physician recommends that the baby sleeps on his stomach, the parents should be sure that the infant's mattress is very firm, possibly tilted up at the head, and that there are no pillows. The baby's head should be turned so that the mouth and nose are completely unobstructed. Carefully watch children who are placed on their stomach.

- Because food allergies may trigger GERD in children, parents may want to discuss a dietary plan with their physician that starts the child on formulas using non-allergenic proteins, and then incrementally adds other foods until symptoms are triggered.

- Proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs), such as omeprazole (Prilosec) and lansoprazole (Prevacid), are drugs that suppress the production of stomach acid. The FDA has approved the PPI esomeprazole (Nexium) by injection for treatment of GERD with erosive esophagitis in children older than 1 month, in whom treatment with oral (by mouth) medication is not possible.

Managing GERD in Children

The same drugs used in adults may be tried in children with chronic GERD. While some drugs are available over the counter, do not give them to children without physician supervision.

- Changes in diet can include eliminating foods that are acidic or possibly associated with reflux, such as tomatoes, chocolate, mint, juices, and carbonated or caffeinated drinks.

- Obese children should try to lose weight.

- Adolescents should avoid smoking.

- Chewing sugarless gum may be helpful.

- Milder medications, such as antacids, are used first. However, long-term use of these drugs is generally not recommended due to side effects such as diarrhea or constipation.

PPIs may also be effective in children. Five different PPIs are approved for use in children and adolescents:

- Esomeprazole (Nexium)

- Lansoprazole (Prevacid)

- Omeprazole (Prilosec)

- Pantoprazole (Protonix)

- Rabeprazole (Aciphex)

With the exception of Protonix, all of the above PPIs are approved for use in children ages 1 to 18.

- H2 blockers are available over the counter and include famotidine (Pepcid AC), cimetidine (Tagamet HB), and nizatidine (Axid AR). Many are FDA approved for children as well as infants. Note: The FDA has issued a warning on Pepcid AC for people with kidney problems. See below in Medications.

- Children treated with H2 blockers and PPIs may have an increased risk of developing respiratory and intestinal infections.

Surgical fundoplication involves wrapping the upper curve of the stomach (fundus) around the esophagus. The goal of this surgical technique is to strengthen the LES. Until recently, surgery was the primary treatment for children with severe complications from GERD because older drug therapies had severe side effects, were ineffective, or had not been designed for children. However, with the introduction of PPIs, many children are able to avoid surgery. It is performed only when medicines are ineffective or for those at risk of severe aspiration.

Surgical fundoplication can be performed laparoscopically through small incisions. Weakening of the LES over the long-term occurs with children as well as adults.

Medications

Antacids neutralize acids in the stomach, and are the drugs of choice for mild GERD symptoms. They may also stimulate the defensive systems in the stomach by increasing bicarbonate and mucus secretion. They are best used alone for relief of occasional and unpredictable episodes of heartburn. Many antacids are available without a prescription. The different brands all rely on various combinations of 3 basic ingredients: magnesium, calcium, or aluminum.

Magnesium

Magnesium salts are available in the form of magnesium carbonate, magnesium trisilicate, and most commonly, magnesium hydroxide (Milk of Magnesia). The major side effect of magnesium salts is diarrhea. Magnesium salts offered in combination products with aluminum (Mylanta and Maalox) balance the side effects of diarrhea and constipation.

Calcium

Calcium carbonate (Tums, Titralac, and Alka-2) is a potent and rapid-acting antacid. It can cause constipation. There have been rare cases of elevated levels of calcium in the blood (hypercalcemia) in people taking large doses of calcium carbonate for long periods of time. This condition can lead to kidney failure and is very dangerous. None of the other antacids has this potential side effect.

Aluminum

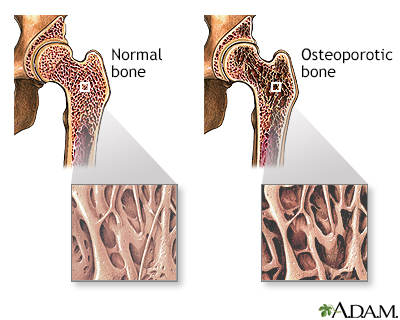

Aluminum salts (Amphogel, Alternagel) are also available. The most common side effect of antacids containing aluminum salts is constipation. People who take large amounts of antacids that contain aluminum may also be at risk for calcium loss, which can lead to osteoporosis.

Osteoporosis is a condition that leads to bone density loss, thinning of bone tissue, and increased vulnerability to fractures. Osteoporosis may result from disease, dietary or hormonal deficiency, or advanced age. Getting regular exercise and taking vitamin D and calcium supplements can reduce and even reverse bone density loss.

Although all antacids work equally well, it is generally believed that liquid antacids work faster and are more potent than tablets. Antacids can interact with a number of drugs in the intestines by reducing their absorption. These drugs include tetracycline, ciprofloxacin (Cipro), propranolol (Inderal), captopril (Capoten), and H2 blockers. Interactions can be avoided by taking the drugs 1 hour before, or 3 hours after taking the antacid. Long-term use of nearly any antacid increases the risk for kidney stones.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) suppress the production of stomach acid and work by inhibiting the protein in the stomach glands that is responsible for acid secretion (the gastric acid pump or proton pump). Recent guidelines indicate that PPIs should be the first drug treatment because they are more effective than H2 blockers. Once symptoms are controlled, people should receive the lowest effective dose of PPIs.

The standard PPI has been omeprazole (Prilosec), which is now available over the counter without a prescription. Newer prescription oral PPIs include esomeprazole (Nexium), lansoprazole (Prevacid), rabeprazole (Aciphex), pantoprazole (Protonix), and the long-acting PPI dexlansoprazole (Kapidex). All are considered equally effective. Most are taken once per day, 30 to 60 minutes before a meal, for 8 weeks. Brand, dosage, and timing can be altered by your physician based on response and side effects. Long-term maintenance therapy with a lower dose is sometimes necessary, but may cause low magnesium levels in some people.

Studies report significant heartburn relief in most people taking PPIs. PPIs are effective for healing erosive esophagitis.

In addition to relieving most common symptoms, including heartburn, PPIs also have the following advantages:

- They are effective in relieving chest pain and laryngitis caused by GERD.

- They may also reduce the acid reflux that typically occurs during strenuous exercise.

People with impaired esophageal muscle action are still likely to have acid breakthrough and reflux, especially at night. PPIs also may have little or no effect on regurgitation or asthma symptoms.

Currently, these drugs are recommended for people with:

- Moderate symptoms that do not respond to H2 blockers

- Severe symptoms

- Respiratory complications

- Persistent nausea

- Esophageal injury

These medications have no effect on non-acid reflux, such as bile backup.

Adverse Effects

Proton-pump inhibitors may cause side effects including headache, diarrhea, constipation, nausea, and itching. However, these side effects are uncommon.

Long-term use of these drugs has been linked to problems caused by poor vitamin or mineral absorption. These include:

- A possible increased risk of hip, wrist, and spine fractures, due to poor calcium absorption from the diet when stomach acidity is reduced. People who are on long-term PPI therapy may need to take a calcium supplement or the osteoporosis drugs, bisphosphonates to reduce their fracture risks.

- Vitamin B12 deficiencies.

There is some evidence that PPIs increase the risk for certain infectious diseases:

- Community-acquired pneumonia and hospital-acquired pneumonia, especially within the first 2 weeks of starting the medication. Researchers do not know the reason for this possible association.

- Clostridium difficile infections, a condition that causes severe diarrhea.

- Intestinal infections caused by Campylobacter and Salmonella.

Pregnant women and nursing mothers should discuss the use of PPIs with their health care provider. Recent studies suggest that PPIs pose an increased risk of birth defects and should be avoided by pregnant women.

PPIs may interact with certain drugs, including:

- Anti-seizure medications (such as phenytoin).

- Anti-anxiety drugs (such as diazepam).

- Blood thinners (such as warfarin or clopidogrel). PPIs may reduce the effectiveness of clopidogrel (Plavix) by nearly 50%, although recent studies suggest that this not clinically significant.

- Methotrexate, by elevating levels in the blood and causing toxic side effects. This drug is commonly used to treat certain cancers and autoimmune disorders.

Some evidence suggests that acid reflux may contribute to the higher risk of cancer in Barrett esophagus, but it is not yet confirmed whether acid blockers have any protective effects against cancer in these patients. Moreover, long-term use of PPIs by people with H pylori may reduce acid secretion enough to cause atrophic gastritis (chronic inflammation of the stomach). This condition is a risk factor for stomach cancer (gastric cancer). To compound concerns, long-term use of PPIs may mask symptoms of stomach cancer and thus delay diagnosis. There have been a few recent clinical reports of an increased risk of stomach cancer with the long-term use of these drugs in some populations. While it is still unclear whether chronic PPI use raises the risk of gastric cancer independently of other factors, these studies may cast doubts on the benefits of long-term use of these drugs.

There had been concerns that the PPIs omeprazole (Prilosec) and esomeprazole (Nexium) might lead to heart attacks or cardiovascular problems. However, after a careful review, the FDA found no evidence of increased cardiovascular risk.

H2 blockers interfere with acid production by blocking or antagonizing the actions of histamine, a chemical found in the body. Histamine stimulates acid secretion in the stomach. H2 blockers are available over the counter and relieve symptoms in about half of people with GERD. It takes 30 to 90 minutes for them to work, but the benefits last for hours. People usually take the drugs at bedtime. Some people may need to take them twice a day.

H2 blockers inhibit acid secretion for 6 to 24 hours and are very useful for people who need persistent acid suppression. They may also prevent heartburn episodes. In some studies, H2 blockers improved asthma symptoms in people with both asthma and GERD. However, they rarely provide complete symptom relief for chronic heartburn and dyspepsia, and they have done little to reduce physician office visits for GERD. While PPIs are the initial treatment of choice, H2 blockers may be helpful as a maintenance therapy or bedtime therapy in addition to PPI in some people.

Brands

Four H2 blockers are available in the United States:

- Famotidine (Pepcid AC, Pepcid Oral). Famotidine is the most potent H2 blocker. The most common side effect of famotidine is headache, which occurs in 4.7% of people who take it. Famotidine is virtually free of drug interactions, but the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued a warning on its use in people with kidney problems.

- Cimetidine (Tagamet, Tagamet HB). Cimetidine is the oldest H2 blocker. It has few side effects, although about 1% of people taking it will have mild temporary diarrhea, dizziness, rash, or headache. Cimetidine interacts with a number of commonly used medications, such as phenytoin (for seizures), theophylline (for respiratory diseases), and warfarin (blood-thinner). Long-term use of excessive doses (more than 3 grams a day) may cause impotence or breast enlargement in men. These problems get better after the drug is stopped.

- Ranitidine (Zantac, Zantac 75, Zantac EFFERdose, Zantac injection, and Zantac Syrup) was recalled from the market by the FDA in 2019 because samples were found to have unacceptable levels of N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA), a known carcinogen. Whether it will ever return to the market is unknown. Ranitidine may provide better pain relief and heal ulcers more quickly than cimetidine in people younger than age 60, but there appears to be no difference in older people. A common side effect associated with ranitidine is headache, occurring in about 3% of people who take it. Ranitidine interacts with very few drugs.

- Nizatidine Capsules (Axid AR, Axid Capsules, Nizatidine Capsules). Nizatidine is nearly free from side effects and drug interactions. A controlled-release form can help alleviate nighttime GERD symptoms.

Drug Combinations:

- Over-the-counter antacids and H2 blockers. This combination may be the best approach for many people who get heartburn after eating. Both classes of drugs are effective in relieving GERD, but they have different timing. Antacids work within a few minutes but are short-acting, while H2 blockers take longer but have long-lasting benefits. Pepcid AC combined with an antacid (calcium carbonate and magnesium) is available as Pepcid Complete.

- PPIs and H2 blockers. Doctors sometimes recommend a nighttime dose of an H2 blocker for people who are taking PPIs twice a day. This is based on the belief that adding the H2 blocker will prevent a rise in acid reflux at night. Some experts recommended that patients who are on PPIs take an H2 blocker only to prevent breakthrough symptoms, such as before a heavy meal.

Long-Term Complications

In most cases, these medications have good safety profiles and few side effects. H2 blockers can interact with other drugs, although some less so than others. In all cases, the physician should be made aware of any other drugs a patient is taking. Anyone with kidney problems should use famotidine only under a doctor's direction. More research is needed into the effects of long-term use of these medications.

Concerns and Limitations

Some experts are concerned that the use of acid-blocking drugs in people with peptic ulcers may mask ulcer symptoms and increase the risk for serious complications.

These drugs do not protect against Barrett esophagus. Also of concern are reports that long-term acid suppression with these drugs may cause cancerous changes in the stomach in patients who are infected with H pylori. Research on this question is still ongoing.

Famotidine is removed primarily by the kidney. This can pose a danger to people with kidney problems. The FDA and Health Canada are advising physicians to reduce the dose and increase the time between doses in people with kidney failure. Use of the drug in those with impaired kidney function can affect the central nervous system and may result in anxiety, depression, insomnia or drowsiness, and mental disturbances.

Caution is warranted in pregnant and nursing mothers as the effects are unknown.

Sucralfate (Carafate) protects the mucus lining in the gastrointestinal tract. It works by sticking to an ulcer crater and protecting it from the damaging effects of stomach acid and pepsin. Sucralfate may be helpful for maintenance therapy in people with mild-to-moderate GERD. Other than constipation, the drug has few side effects. Sucralfate interacts with a wide variety of drugs, however, including warfarin, phenytoin, and tetracycline.

Prokinetic drugs help the stomach empty its contents more quickly and strengthen the esophageal sphincter. These are considered second-line access drugs due to side effects. The currently available prokinetic is Metoclopramide (Reglan).

Surgery

The standard surgical treatment for GERD is fundoplication. The goal of this procedure is to:

- Increase LES pressure and prevent acid backup (reflux)

- Repair a hiatal hernia

There are 2 primary approaches:

- Open Nissen fundoplication (the more invasive technique)

- Laparoscopic fundoplication

Candidates

Fundoplication is recommended for people whose condition includes 1 or more of the following:

- Esophagitis (inflamed esophagus)

- Symptoms that persist or come back in spite of antireflux drug treatment

- Strictures (or narrowing) in the esophagus

- Failure to gain or maintain weight (in children)

Fundoplication has little benefit for patients with impaired stomach motility (an inability of the muscles to contract normally).

The Open Nissen Fundoplication Procedure

Until recently, the Nissen fundoplication was the fundoplication procedure most often used for GERD. This is called an open procedure because it requires wide surgical incisions.

- With this procedure, the physician wraps the upper part of the stomach (fundus) completely around the esophagus to form a collar-like structure.

- The collar places pressure on the LES and prevents stomach fluids from backing up into the esophagus.

- Open fundoplication requires a hospital stay of 6 to 10 days.

Laparoscopic Fundoplication

The standard invasive fundoplication procedure has been replaced in many cases by a less invasive surgical procedure called laparoscopy. In the operation:

- Tiny incisions are made in the abdomen.

- Small instruments and a tiny camera are inserted into tubes placed into the incisions, through which the surgeon can view the region.

- The surgeon creates a collar using the fundus. However, with the laparoscopic procedure, the collar wraps only around one half, or 180° of the esophagus. As a result, the procedure is also called a partial fundoplication.

When performed by experienced surgeons, results are equal to those of standard open fundoplication, but with a faster recovery time and fewer side effects.

Overall, laparoscopic fundoplication appears to be safe and effective in people of all ages, even babies. Five years after undergoing laparoscopic fundoplication for GERD, people report a near-normal quality of life, and say they are satisfied with their treatment choice. In a 5 year trial, laparoscopic fundoplication provided better relief of symptoms compared to medical management. Laparoscopic surgery also has a low reoperation rate, about 1%.

Laparoscopy is more difficult to perform in certain people, including those who are obese, have a short esophagus, or have a history of previous surgery in the upper abdominal area. It may also be less successful in relieving atypical symptoms of GERD, including cough, abnormal chest pain, and choking. In about 8% of laparoscopies, it is necessary to convert to open surgery during the procedure because of unforeseen complications.

Other Variations and Alternatives

There are now different fundoplication procedures.

- Toupet fundoplication and Thal fundoplication use only a partial wrap. Partial fundoplication procedures may be more effective in people with poor or no esophageal muscle movement. Those with normal muscle movement may do better with the full-circle wrap.

- Other procedures use a very short and "floppy" Nissen full wrap.

Many surgeons report that such limited fundoplications help patients start eating and get released from the hospital sooner, and they have a lower incidence of complications (trouble swallowing, gas bloating, and gagging) than the full Nissan fundoplication.

In addition to fundoplication, other surgical procedures are currently being investigated but remain unproven as effective treatments for GERD, including:

- Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

- Magnetic sphincter augmentation by implantation of a titanium magnetic beads ring device (LINX).

- Electrical stimulation of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES).

Postoperative Problems and Complications after Fundoplication

Problems after surgery can include a delay in intestinal functioning, causing bloating, gagging, and vomiting. These side effects usually go away in a few weeks. If symptoms last or start weeks or months after surgery, particularly if there is vomiting, surgical complications are likely. Complications include:

- An excessively wrapped fundus. This is fairly common and can cause difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), as well as gagging, gas, bloating, or an inability to burp. (A follow-up procedure that dilates the esophagus using an inflated balloon may help correct dysphagia, although it cannot treat other symptoms.)

- Bowel obstruction.

- Wound infection.

- Injury to nearby organs.

- Respiratory complications, such as a collapsed lung. These are uncommon, particularly with laparoscopic fundoplication.

- Muscle spasms after swallowing food. This can cause intense pain, and people may need to eat a liquid diet, sometimes for weeks. This is a rare complication in most people, but the risk can be very high in children with brain and nervous system (neurologic) abnormalities. Such children are already at high risk for GERD.

Outcomes

In general, the long-term benefits of these procedures are similar. Fundoplication relieves GERD-induced coughing and other respiratory symptoms in up to 85% of people. Its effect on asthma associated with GERD, however, is unclear. Many people still require anti-GERD medications or experience new symptoms (such as gas, bloating, and trouble swallowing) after surgery. Most of these new symptoms occur more than a year after surgery. Fundoplication does not cure GERD, and evidence suggests that the procedure does not reduce the risk for esophageal cancer in high-risk patients, such as those with Barrett esophagus. However, fundoplication has very good long-term results, especially when performed by an experienced surgeon, and few people need to have a repeat procedure.

Reasons for Treatment Failure

Some studies have reported that 3% to 6% of people need repeat operations, usually because of continuing reflux symptoms and swallowing difficulty (dysphagia). Repeat surgery usually has good success. However, these surgeries can also lead to greater complications, such as injury to the liver or spleen.

Procedures to Remove the Mucus Lining

Various techniques or devices have been developed to remove the mucus lining of the esophagus. The intention is to remove early cancerous or precancerous tissue (high-grade dysplasia) and allow regrowth of new and hopefully healthy tissue in the esophagus.

Such techniques include photodynamic therapy (PDT), surgical removal of the abnormal lining, or ablation techniques, such as the use of laser, to destroy the abnormal lining. These techniques are done using an endoscope.

People with Barrett esophagus who are most likely to benefit from these techniques have:

- A type of cancer of the esophagus called adenocarcinoma, but only when the cancer has not invaded deeper than the mucosal lining of the esophagus

- Pre-cancerous tissue called high-grade dysplasia

Unfortunately, the benefits do not last in all people. These procedures also carry potential complications, such as swallowing problems, which patients should discuss with their physicians.

Esophagectomy

Esophagectomy is the surgical removal of all or part of the esophagus. People with Barrett esophagus who are otherwise healthy are candidates for this procedure if biopsies show they have high-grade dysplasia or cancer. After the esophagus is removed, a new conduit for foods and fluids must be created to replace the esophagus. Alternatives include the stomach, colon, and a part of the small intestine called the jejunum. The stomach is the optimal choice.

A number of endoscopic treatments are being used or investigated for increasing LES pressure and preventing reflux, as well as for treating severe GERD and its complications. Examples include suturing, using radiofrequency ablation, or injecting silicone into the LES. Researchers find that endoscopic therapies for GERD may relieve symptoms and reduce the need for antireflux medications, although they are not as effective as laparoscopic fundoplication. Endoscopic procedures are also being done along with fundoplication.

Transoral Flexible Endoscopic Suturing

Transoral flexible endoscopic suturing (sometimes referred to as Bard's procedure) uses a tiny device at the end of the endoscope that acts like a miniature sewing machine. It places stitches in 2 locations near the LES, which are then tied to tighten the valve and increase pressure. There is no incision and no need for general anesthesia.

Radiofrequency Ablation

Radiofrequency energy generated from the tip of a needle (sometimes called the Stretta procedure) heats and destroys tissue in problem spots in the LES. It has been shown to reduce symptoms of GERD. People may experience some chest or stomach pain afterward. Few serious side effects have been reported, although there have been reports of perforation, hemorrhage, and even death.

Dilation Procedures

Strictures (abnormally narrowed regions) may need to be dilated (opened) with endoscopy. Dilation may be performed by inflating a balloon in the passageway, or by passage of a bougie device. About 30% of people who need this procedure require a series of dilation treatments over a long period of time to fully open the passageway. Long-term use of PPIs may reduce the duration of treatments.

Resources

- National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse (NDDIC) -- www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases

- American Gastroenterological Association -- www.gastro.org

- American College of Gastroenterology -- gi.org

- American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy -- www.asge.org

- The Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract -- www.ssat.com

- North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition -- www.naspghan.org

- International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders (IFFGD) -- www.iffgd.org

References

American Society for Gastrointestinal endoscopy (ASGE) Standards of Practice Committee, Qumseya B, Sultan S, Bain P, et al. ASGE guideline on screening and surveillance of Barrett's esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;90(3):335-359.e2. PMID: 31439127 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31439127.

Brusselaers N, Wahlin K, Engstrand L, Lagergren J. Maintenance therapy with proton pump inhibitors and risk of gastric cancer: a nationwide population-based cohort study in Sweden. BMJ Open. 2017;7(10):e017739. PMID: 29084798 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29084798.

Cheung KS, Chan EW, Wong AYS, Chen L, Wong ICK, Leung WK. Long-term proton pump inhibitors and risk of gastric cancer development after treatment for Helicobacter pylori: a population-based study. Gut. 2018;67(1):28-35. PMID: 29089382 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29089382.

Desart K, Rossidis G, Michel M, Lux T, Ben-David K. Gastroesophageal reflux management with the LINX® system for gastroesophageal reflux disease following laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19(10):1782-1786. PMID: 26162926 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26162926.

Freedberg DE, Kim LS, Yang YX. The risks and benefits of long-term use of proton pump inhibitors: Expert review and best practice advice from the American Gastroenterological Association. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(4):706-715. PMID: 28257716 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28257716.

Iwakiri K, Kinoshita Y, Habu Y, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for gastroesophageal reflux disease 2015. J Gastroenterol. 2016;51(8):751-67. PMID: 27325300 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27325300.

Khan S, Matta SVR. Gastroesophageal reflux disease. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 349.

Kim SE, Soffer E. Electrical stimulation for gastroesophageal reflux disease: current state of the art. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2016;9:11-19. PMID: 26834494 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26834494.

Kung YM, Hsu WH, Wu MC, et al. Recent advances in the pharmacological management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62(12):3298-3316. PMID: 29110162 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29110162.

Maes ML, Fixen DR, Linnebur SA. Adverse effects of proton-pump inhibitor use in older adults: a review of the evidence. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2017;8(9):273-297. PMID: 28861211 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28861211.

Moore M, Afaneh C, Benhuri D, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux disease: A review of surgical decision making. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;8(1):77-83. PMID: 26843915 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26843915.

Papachrisanthou MM, Davis RL. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux and Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: 1 Year to 18 Years of Age. J Pediatr Health Care. 2016;30(3):289-94. PMID: 26432163 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26432163.

Patti MG. An Evidence-Based Approach to the Treatment of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(1):73-8. PMID: 26629969 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26629969.

Richter JE, Rubenstein JH. Presentation and Epidemiology of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(2):267-276. PMID: 28780072 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28780072.

Richter JE, Vaezi MF. Gastroesophageal reflux disease. In: Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ, eds. Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 46.

Rosen R, Vandenplas Y, Singendonk M, et al. Pediatric Gastroesophageal Reflux Clinical Practice Guidelines: Joint Recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;66(3):516-554. PMID: 29470322 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29470322.

Sandhu DS, Fass R. Current trends in the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gut Liver. 2018;12(1):7-16. PMID: 28427116 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28427116.

Savarino E, Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, Pandolfino JE, Roman S, Gyawali CP; International Working Group for Disorders of Gastrointestinal Motility and Function. Expert consensus document: Advances in the physiological assessment and diagnosis of GERD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14(11):665-676. PMID: 28951582 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28951582.

Seo HS, Choi M, Son SY, et al. Evidence-Based Practice Guideline for Surgical Treatment of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease 2018. J Gastric Cancer. 2018;18(4):313-327. PMID: 30607295 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30607295.

Shaheen NJ, Falk GW, Iyer PG, Gerson LB; American College of Gastroenterology. ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Barrett's Esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(1):30-50. PMID: 26526079 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26526079.

Spechler SJ, Hunter JG, Jones KM, et al. Randomized Trial of Medical versus Surgical Treatment for Refractory Heartburn. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(16):1513–1523. PMID: 31618539 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31618539.

Yates RB, Oelschlager BK, Pellegrini CA. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and hiatal hernia. In: Townsend CM Jr, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL, eds. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery. 20th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017:chap 42.

Reviewed By: Michael M. Phillips, MD, Clinical Professor of Medicine, The George Washington University School of Medicine, Washington, DC. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.