Endometriosis - InDepth

Highlights

Endometriosis

Endometriosis is a gynecological condition that occurs when cells from the lining of the womb (uterus) grow in other areas of the body.

Endometriosis Symptoms

Endometriosis symptoms vary widely, and some women with the condition have no symptoms. The most common symptom of endometriosis is chronic pelvic pain. Other symptoms can include:

- Pelvic pain, especially around the time of menstruation (dysmenorrhea)

- Pain during sexual intercourse (dyspareunia)

- Heavy or irregular menstrual bleeding

- Sleep problems

- Cyclical abdominal pain

- Intermittent diarrhea and constipation

- Painful or difficult urination, frequent urination, or blood in the urine

- Painful bowel movements

Infertility and Endometriosis

Endometriosis rarely causes a complete inability to conceive, but it can contribute to reduced fertility.

Treatment

Treatment options for endometriosis include:

Watchful Waiting.

Delaying treatment may be most appropriate for women with mild endometriosis or those who are approaching the age of menopause.Drugs.

First-line drug therapies are estrogen-progestin oral contraceptives, which are often used along with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Progestin-only pills, injections, or an intrauterine device (IUD) may also be used. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist drugs are another option.Surgery.

Conservative surgical approaches, such as laparoscopic ablation, remove endometrial implants and cysts without removing reproductive organs. Conservative surgery can help improve fertility. Hysterectomy, the surgical removal of the uterus, may be recommended in severe cases of endometriosis.

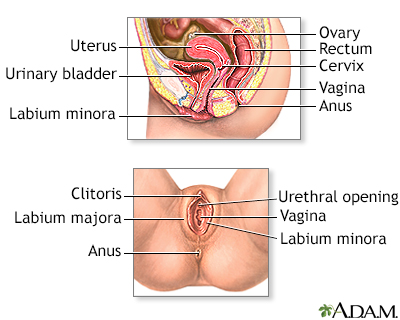

Introduction

Endometriosis is a condition in which the cells that line the uterus grow outside of the uterus in other areas, such as the ovaries or in the pelvis. The condition can interfere with a woman's ability to become pregnant. Endometriosis can also cause severe pelvic pain, especially during menstruation.

Endometriosis is a common gynecological condition and a common cause of chronic pelvic pain, affecting more than 10% of women of reproductive age. It is chronic and may be a painful and progressive disease. However, the causes of endometriosis are unknown, it is widely variable in symptoms and severity, and it can only be diagnosed definitively with surgery (usually laparoscopy). The average time to endometriosis diagnosis in the United States is currently over 7 years. There is a high probability that endometriosis is the likely cause for the majority of initial visits by young women to physician's offices for severe dysmenorrhea (painful menses).

Endometrial Implants

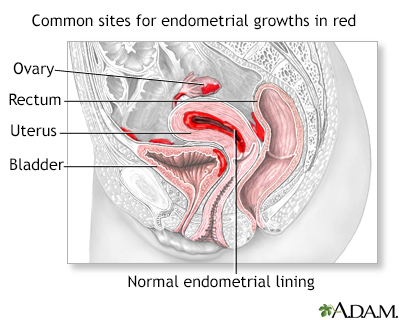

Endometriosis occurs when cells from the tissue layer lining the uterus (

endometrium

) form implants that attach, grow, and functionoutside

the cavity of the uterus, often in the pelvic region. The endometriosis implants contain both glands (an epithelial tissue) and stroma (a connective tissue) from the endometrial layer.A related condition is adenomyosis, in which endometrial glands are found deep within the muscle walls of the uterus. Adenomyosis can also cause pelvic pain similar to that caused by endometriosis. More information regarding adenomyosis is given below.

Endometrial cells contain receptors that respond to the female hormones estrogen and progesterone, which promote uterine lining growth and thickening. When these cells become implanted in organs and structures outside the uterus, these hormonal activities continue to occur, causing bleeding, inflammation, and scarring.

Endometriosis is a condition in which cells that normally line the uterus (endometrium) grow on other areas of the body, causing pain and abnormal bleeding.

Endometrial implants vary widely in size, shape, and color. Over the years, they may diminish in size or disappear, or they may grow.

- Early implants are often very small and look like clear pimples.

- If they continue to grow, they may form flat injured areas (lesions), small nodules, or cysts usually within the ovaries called

endometriomas

, or chocolate cysts. - Endometriomas can range in size from smaller than a pea to larger than a grapefruit.

- Implants may also vary in color; they may be colorless, red, very dark brown, or black. So-called chocolate cysts are endometriomas filled with thick, old, dark brown blood.

Location of Implants

Implants can form in many areas, most commonly in the following locations in the pelvis:

- Ovaries.

- Fallopian tubes.

- Uterine surface.

- Cul-de-sac, an area between the uterus and rectum.

- Bowel.

- Bladder.

- Rectum or sigmoid colon.

- Ureter.

- The

peritoneum

. This is the smooth surface lining that covers the inner wall of the abdomen and folds over the organs in the pelvic area.

Rarely, remote sites of endometriosis may include the spinal column, brain, nose, umbilicus, lungs, pelvic lymph nodes, the forearm, and the thigh.

Process of Endometriosis

The process of endometriosis mimics the stages of the menstrual cycle:

- Each month, the endometrial implants respond to the monthly cycle just as they would in the uterus. They fill with blood, thicken, break down, and bleed.

- Products of the endometrial process cannot be shed through the vagina as are menstrual blood and debris. Instead, the implants develop into collections of blood that form cysts, spots, or patches.

- Lesions may grow or reseed as the cycle continues.

The lesions are not cancerous, but they can develop to the point that they cause obstruction or

adhesions

(web-like scar tissue) that attach to and bind together nearby pelvic organs, causing pain, inflammation, and sometimes infertility. Endometriosis pain may also be due to innervation to the endometrial implants, and to implant production of inflammatory molecules called prostaglandins. While very uncommon, endometriotic lesions may rarely become cancerous.Causes

Doctors do not know the exact cause of endometriosis. A combination of genetic, biological, and environmental factors may work together to trigger the initial process, produce implantation, and cause subsequent reseeding and spreading of the implants.

Theories of the cause of endometriosis include:

Retrograde Menstruation.

Retrograde menstruation occurs during a woman's period when menstrual tissue flows backward through the fallopian tubes rather than out through the vagina. In some cases, the redistributed endometrial tissue may attach and grow in areas outside the uterus, forming endometriosis implants. This theory does not fully explain endometriosis, however. Most women have some retrograde menstruation, but not all of them develop endometriosis. Consequently, other factors must explain why uterine lining tissue implants and grows in areas outside the uterus.Exposure to Estrogen.

Prolonged exposure to estrogen may play a role in the development of endometriosis. Causes of prolonged exposure to the body's own estrogen include early-age menstruation, short menstrual cycles, and obesity. Sources of external estrogen exposure include natural and synthetic chemicals that disrupt the body's endocrine system.Impaired Immune System.

Another theory is that women who develop endometriosis have an impaired immune system that fails to identify and destroy endometrial tissue that grows outside of the uterus. Some researchers think that endometriosis is a type of autoimmune condition, in which the immune system launches an attack on its own cells and tissue. There appears to be a relatively high incidence of other inflammatory autoimmune disorders (multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and lupus) among women with endometriosis. It is unclear, however, how this response relates to endometriosis itself and whether endometriosis should be treated as an autoimmune condition.Inflammatory Response.

The damage, infertility, and pain produced by endometriosis may be due to an overactive response by the immune system to the early presence of endometrial implants. The body, perceiving the implants as hostile, launches an attack. Levels of large white blood cells called macrophages are elevated in endometriosis. Macrophages produce very potent factors, which include cytokines (particularly those known as interleukins) and prostaglandins. Such factors are known to produce inflammation and damage in tissues and cells.Metaplasia

. Another theory for the origin of endometrial cells outside of the uterus is transformation from another type of cell (called metaplasia). Endometrial implants could result from metaplasia of peritoneal cells, which are derived from the same type of epithelial tissue as the normal endometrium. This theory would explain endometriosis in women who have had a total hysterectomy (surgery to remove the uterus and ovaries) and are not having hormone replacement therapy.

Risk Factors

Age

Endometriosis can develop in teenagers and adult women of all ages, but it is most typically diagnosed in women ages 25 to 50 years.

Family History

A family history of endometriosis, especially in a mother or sister, increases a woman's likelihood of developing it herself.

Not Having Had Children

Pregnancy appears to protect against endometriosis, while never having had children is associated with increased risk. However, endometriosis can still occur in women who have had children.

Dietary Factors

Some studies suggest that consumption of red meat and trans fats may increase the risk of developing endometriosis, while consumption of fruits, green leafy vegetables, and omega-3 fatty acids (found in fish) may be protective. Other studies have not verified this association.

Menstrual History

Women at increased risk for endometriosis tend to have more problems with menstruation. They often have a shorter than normal cycle, heavier periods, and longer periods. They may also have begun menstruating at a younger than average age.

Complications

Pain

The inflammatory response due to endometriosis causes pelvic pain. It is often more severe near or during menses. Adhesions can also cause significant pain. They are dense, web-like structures of scar tissue that can attach to nearby organs and cause damage to tissues and scarring, damage to nerves, or damage to the blood supply of different organs. Pelvic pain is the most common complaint for women with endometriosis, and it can significantly impair the quality of life, including work and social activities. The pelvic pain associated with endometriosis is usually chronic (lasting more than 6 months). Pain may also occur in the abdomen and back.

Infertility

Infertility is another main complication of endometriosis. More severe endometriosis is very likely to lead to infertility. Endometriosis rarely causes an absolute inability to conceive, but it can reduce fertility both directly and indirectly:

- If implants occur in or on the fallopian tubes, they may block the egg's passage.

- Implants that occur in the ovaries prevent the release of the egg.

- Inflammation due to endometriosis may interfere with normal sperm and egg function and prevent conception.

- Adhesions that form among the uterus, ovaries, and fallopian tubes can prevent the transfer of the egg to the tube.

Effects on Other Parts of the Pelvic Region

Implants can also occur in the bladder (although less commonly) and cause pain and even bleeding during urination. Implants also sometimes form in the intestine and cause painful bowel movements, constipation, or diarrhea.

Symptoms

Not all women with endometriosis have symptoms. When symptoms occur, pain is the main one.

Many women with endometriosis have chronic pain in the pelvic area (the lower part of the trunk of the body). Chronic pelvic pain lasts more than 6 months and is not necessarily related to menstruation. The pain is often a severe cramping that occurs on both sides of the pelvis, radiating to the lower back and rectal area and even down the legs. The pain may be continuous or it may come and go. Pain tends to worsen over time.

The severity of the pain varies widely and does not appear to be related to the extent of the endometriosis itself. In other words, a woman can have very small or few implants and have severe pain, while some women with extensive endometriosis may have very few signs of the disorder except for infertility. Large cysts (endometriomas) can rupture or leak and cause very severe pain at any time.

Pain caused by endometriosis may be associated with:

Menstruation.

Women with endometriosis typically have heavy or prolonged menstrual bleeding (menorrhagia), and very painful menstrual cramps (dysmenorrhea). Women may also experience pelvic pain at other times during their menstrual cycle and they may have spotting or bleeding between periods. Menstrual pain may worsen over time.Sexual Intercourse.

Endometriosis can cause pain during or after sexual intercourse (dyspareunia).Urination and Bowel Movements.

Pain during defecation or urination may be especially severe during menstrual periods. Women may also experience other gastrointestinal problems, such as diarrhea, constipation, or bloating.

Diagnosis

Because endometriosis symptoms do not always appear, or may be caused by other conditions, a diagnosis cannot be based on symptoms alone. Laparoscopy, an invasive diagnostic procedure, is considered the only definitive method for diagnosing endometriosis. However, a trial using a hormonal drug may be used to confirm or rule out endometriosis. More recently, clinicians are also considering combining clinical diagnosis with non-invasive imaging in order to reach a diagnosis for endometriosis without exploratory laparoscopy.

Pelvic Exam

After collecting your symptom report and medical history, the doctor will perform a physical and pelvic exam. During the pelvic exam, the doctor will evaluate the size and position of the ovaries and check for tender masses or nodules behind the cervix.

Imaging Tests

An abdominal or transvaginal ultrasound is performed in cases where other conditions are suspected, such as uterine fibroids, ovarian cysts, or ectopic pregnancy. This non-invasive imaging technique can detect endometriomas, cysts that are usually located on the ovaries and filled with thick dark blood. Ultrasound can pick up cysts larger than 1 cm (about 1/3 inch), but it will miss smaller cysts, or small and shallow endometrial implants on the surface of ovaries or on the peritoneum (lining of the pelvis). Other imaging techniques, such as computed tomography (CT) scanning or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), may occasionally be used.

Laparoscopy

Diagnostic laparoscopy is used to confirm a suspected diagnosis of endometriosis and to evaluate the severity of the condition. It may also be used to treat endometriosis. During laparoscopy, the surgeon determines the number, size, and location of endometrial implants and adhesions. This information can help in staging endometriosis and in making treatment decisions.

The procedure involves the doctor making a small incision in the abdomen and inserting a thin fiber-optic tube (the laparoscope). The laparoscope is equipped with a small telescopic lens, which enables the doctor to view the uterus, ovaries, tubes, and peritoneum (lining of the pelvis) on a video monitor. Laparoscopy normally requires a general anesthetic, although the patient can go home the same day. [For more information on laparoscopy, see the "Conservative Surgery" section of this report.]

Other Tests

A number of blood and urine tests called biomarkers have been evaluated alone or in combination with imaging tests. None have appeared to be helpful in improving the diagnosis of endometriosis without invasive procedures such as laparoscopy.

Ruling Out Conditions with Similar Symptoms

Many conditions cause pelvic pain. In many cases, the cause is unknown, and the condition often resolves on its own. However, some causes of pelvic pain can be serious and should be ruled out during a work-up for endometriosis.

Primary Dysmenorrhea

Primary dysmenorrhea is defined as pelvic pain associated with menstruation in the absence of an identifiable cause. Commonly, its onset occurs in women younger than the usual age of dysmenorrhea associated with endometriosis. Primary dysmenorrhea is common.

Adenomyosis

A condition called adenomyosis occurs when nodules (knots) of endometrial tissue develop within the deep muscle layers of the uterus. This disorder is often classified as endometriosis, but adenomyosis is a different disease. (Endometriosis occurs when endometrial tissue grows and functions outside the uterus.)

Adenomyosis is a significant cause of severe pelvic pain and menstrual irregularities. It typically occurs in women who have uterine fibroids, women age 40 to 50, and women who have had children. Women, who have had surgery for endometriosis, yet continue to suffer from menstrual and pelvic pain may actually have adenomyosis.

Other Causes of Pelvic Pain

Many conditions cause pelvic pain that may or may not be related to menstruation. Some causes of pelvic pain that can be serious and should be ruled out include:

- Pelvic inflammatory disease (which results from infections in the pelvic area, such as gonorrhea or chlamydia infections)

- Uterine fibroids

- Miscarriage

- Ectopic pregnancy (when the fertilized egg implants in an area outside of the uterus, usually the fallopian tube)

- Pelvic cancer (rare)

- Uterine polyps

- The use of an intrauterine device (IUD) for contraception

- History of sexual abuse or trauma

Conditions that may mimic symptoms of endometriosis, but which are unrelated to problems in the reproductive organs include:

- Severe kidney or urinary tract infections

- Celiac disease

- Appendicitis

- Interstitial cystitis

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Diverticulitis

- Irritable bowel syndrome

Treatment

Treatment of endometriosis is often managed by different specialists. A multidisciplinary team may include specialists in gynecology, reproductive endocrinology and infertility, urology, general surgery, immunology, psychology, pain management, and others.

There is no perfect way of managing endometriosis. The three basic treatment approaches are:

- Watchful waiting (conservative therapy to relieve symptoms)

- Hormonal therapy (to reduce the size or activity of endometrial implants)

- Surgery (to reduce endometrial implants, restore fertility, or possibly cure the condition)

The choice depends on a number of factors, including the woman's symptoms, her age, whether fertility is a factor, and the severity of the disease.

Watchful Waiting

Delaying treatment may be most appropriate for women with mild endometriosis or those who are approaching the age of menopause.

Women may also use lifestyle modifications, such as exercise and relaxation, to cope with their pain. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin, generic) and naproxen (Aleve, generic), or acetaminophen (Tylenol, generic), can help provide some pain relief.

Hormonal Therapy

Hormonal therapies are used to mimic states in which ovulation does not occur (pregnancy or menopause) or to directly block ovulation. These hormonal treatments actually suppress natural hormone production and are the preferred and most effective treatment option for treating symptoms of endometriosis and minimizing the progression of the disease.

Hormonal drugs include oral contraceptives (a first-line treatment), progestins, GnRH agonists, and (rarely) danazol. They can be very effective in relieving endometriosis symptoms, especially pain. Some of these drugs may also be used after surgery to help prevent recurrence of endometriosis. Downsides of these drugs include:

- None of these drugs can cure the problem. Symptoms recur in about half of patients within 5 years of treatment.

- Continuous oral contraceptives are frequently given for pain control after endometriosis is diagnosed.

- These drugs do not resolve the infertility that may be associated with endometriosis.

- Side effects of some of these drugs can be unpleasant.

- Women who take GnRH agonists, danazol, or similar drugs should use non-hormonal barrier birth control methods (the diaphragm, cervical cap, or condoms) because these drugs can increase the risk for birth defects.

Surgery

Surgery is an option for women who:

- Have severe pain that does not respond to watchful waiting and medical treatment.

- Want to become pregnant and endometriosis is most likely the major contributor to infertility.

There are two basic surgical approaches for endometriosis:

Conservative Surgery (Laparoscopy or Laparotomy).

Conservative surgery is the most often used surgical approach for endometriosis. It uses minimally invasive laparoscopy, or sometimes laparotomy (conventional "open" surgery through normal incision), to remove the endometrial implants without removing any normal tissue or reproductive organs. It is a good option for women who wish to become pregnant or who cannot tolerate hormone therapy. Endometriosis sometimes recurs after conservative surgery, however. The risk for recurrence or residual pain after any procedure increases with the severity of the condition, particularly if endometriosis has affected areas outside the uterus.Radical Surgery (Hysterectomy).

In some cases, hysterectomy offers the best option for patients with severe pain who do not desire a pregnancy. Younger patients can often have only a hysterectomy while leaving one or both of their ovaries intact. Removing only the uterus with hysterectomy has the same risk for recurrence as conservative surgery. Removing both ovaries (bilateral oophorectomy) along with the uterus is usually effective in relieving pain, however recurrence is still possible. Estrogen replacement therapy can be used after removal of both ovaries.

In choosing between hysterectomy (with or without removal of the ovaries) and conservative surgeries, age and the desire for children are important factors.

Nerve Surgery for Pelvic Pain

Laparoscopic uterine nerve ablation (LUNA) and laparoscopic presacral neurectomy (LPSN) are procedures that aim to reduce chronic pelvic pain by destroying or interrupting the nerves that attach the uterus to the pelvic bone. Some small studies have shown more benefits for LPSN than for LUNA.

LPSN appears to work best when combined with laparoscopic ablation of endometrial implants (conservative surgery). Stronger evidence is needed before these procedure can be recommended for women with chronic pelvic pain associated with endometriosis. Many insurance companies consider these procedures experimental and will not pay for them.

Treating Infertility in Patients with Endometriosis

For women with severe endometriosis who want to become pregnant, conservative surgery (typically laparoscopy) is the appropriate approach for improving fertility. Hormonal therapies that treat endometriosis itself, such as GnRH agonist or progestins, generally do not help fertility, rather they actually prevent infertility. If surgery fails, fertility drugs and assisted reproductive technologies, such as in vitro fertilization, are options. Women with endometriosis who are trying to conceive should discuss all treatment options with a fertility specialist.

Medications

The basic approach in hormonal treatments for endometriosis is to block production of female hormones (estrogen and progesterone) or to prevent ovulation. Hormonal drugs are used for pain relief only. They do not improve fertility rates and in some cases may delay conception.

Specific hormonal drugs may have different effects for women with endometriosis:

Inducing Pseudopregnancy.

Oral contraceptives that contain estrogen and a progestin mimic a pregnant state and block ovulation. (Progestins are synthetic forms of progesterone). Progestin may also be used alone, since it has specific effects that can cause the endometrial tissue to atrophy (shrink).Inducing Pseudomenopause.

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists reduce estrogen and progesterone to their lowest levels. The low hormone levels are similar to those found in postmenopausal women.Inducing On-going Blockage of Ovulation.

Danazol, a derivative of male hormones, is a powerful ovulation blocker but has very unpleasant side effects. It is rarely used nowadays.

Most women achieve pain relief after taking these drugs. To date, comparison studies have found few differences in effectiveness among the major hormonal treatments. Differences occur mostly in their side effects. Women should discuss the effects of particular medications with their doctors to determine the best choice.

Oral Contraceptives

Oral contraceptives (OCs), commonly called birth control pills or "the Pill," contain combinations of an estrogen and a progestin. Combined oral contraceptives are a first-line treatment for endometriosis pain. They are generally used along with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen.

Oral contraceptives may be used either before surgery or after laparoscopic removal of endometrial tissue to prevent current symptoms.

When used throughout a menstrual cycle, OCs suppress the actions of other reproductive hormones (luteinizing hormone [LH] and follicle stimulating hormone [FSH]) and prevents ovulation. There are many brands available. The estrogen compound used in most oral contraceptives is estradiol. Many different progestins are used, and there are many brands. None to date have proven to be better than others. Women should discuss the best options for their individual situations with their doctor.

Standard OCs come in a 28-pill pack that contains 21 active pills and 7 inactive pills. Women with severe pain who have not been helped by standard combination OCs may benefit from switching to continuous-dosing combination OCs. Continuous-dosing oral contraceptives aim to reduce, or even eliminate, monthly periods and thereby prevent the pain and discomfort that often accompanies menstruation. These OCs contain a combination of estradiol and the progestin levonorgestrel; the hormonally active pills are taken continuously without a break.

Estrogen and progestin each cause different side effects. The most serious side effects are due to the estrogen in the combined pill. Uncommon but more dangerous complications of OCs include high blood pressure and deep-vein blood clots (thrombosis), which may contribute to heart attack or stroke, particularly in older women who smoke.

Progestins

Progestin alone may be helpful for women whose pain has not been relieved with combination estrogen-progestin oral contraceptives. Some doctors recommend progestins as the first choice for women with endometriosis who do not want to become pregnant.

Progestins can prevent ovulation and reduce the risk for endometriosis in the following ways:

- Block luteinizing hormone (LH), one of the reproductive hormones important in ovulation

- Change the lining of the uterus and cause it to shrink (atrophy)

- Provide pain relief equivalent to the more powerful hormone drugs

Specific Progestins

Progestins are available in various forms. They include:

Intrauterine Device.

The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system, or LNG-IUS (Mirena, Kyleena, Liletta, and Skyla) is very effective for treating heavy menstrual bleeding (menorrhagia), and studies indicate that it may help control the symptoms of minimal-to-moderate endometriosis pain. Progestin released by the IUD mainly affects the uterus and cervix and causes fewer widespread side effects than other forms of progestins. Research suggests that the LNG-IUS works as well as GnRH agonists in managing endometriosis pain, and causes less loss of estrogen.Injection.

Medroxyprogesterone (Depo-Provera, also known as DMPA) is administered by injection every 3 months. (A low-dose formulation is called Depo-subQ Provera 104.) Depo-Provera can cause loss of bone mineral density, a condition associated with osteoporosis, but GnRH agonists may cause even more bone thinning. Because of the risk for reduced bone density, Depo-Provera should not be used for longer than 2 years. Depo-Provera can cause persistent infertility for up to 22 months after the last injection.Pill.

Oral progestins include medroxyprogesterone (Provera, generic) and norethindrone (Micronor, generic). Norethindrone is also known as norethisterone.

Side Effects of Progestins

Side effects of progestin occur in both the combination oral contraceptives and any contraceptive that uses only progestin, although they may be less or more severe depending on the form and dosage of the contraceptive. The most common side effects include:

- Changes in uterine bleeding, such as higher amounts during periods, spotting and bleeding between periods (called break-through bleeding), or absence of periods

- Weight gain

- Water retention and swelling in the face, ankles, or feet

- Breast tenderness

- Headaches

- Nausea

- Mood changes

GnRH Agonists

Gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists are effective hormone treatments for endometriosis. They block the release of the reproductive hormones LH (luteinizing hormone) and FSH (follicular-stimulating hormone). As a result, the ovaries stop ovulating and no longer produce estrogen. Ovulation and menstruation resume around 4 to 10 weeks after stopping the drug. The specific length of time depends on the type of GnRH agonist used.

Prescribing low dose of hormones in the form of birth control pills along with GnRH agonists can help relieve some of the menopausal-type side symptoms and help prevent osteoporosis, without reducing the effectiveness of GnRH treatment. This approach is called add-back therapy.

Specific GnRH Agonists

GnRH agonists include the implant goserelin (Zoladex), a monthly injection of leuprolide (Lupron, Depot, generic), the nasal spray nafarelin (Synarel), and most recently, an oral preparation, elagolix (Orilissa).

Side Effects and Complications

Common side effects (which can be severe in some women) include menopause-like symptoms, including hot flashes, night sweats, vaginal dryness, weight change, and depression. The side effects vary in intensity depending on the GnRH agonist. They may be more intense with leuprolide and persist after the drug has been stopped.

The most important concern is possible osteoporosis from estrogen loss. To help protect the bones, doctors may prescribe "add-back therapy," with a supplement of combination estrogen-progestin. Because of estrogen loss side effects, doctors generally recommend that women not take GnRH agonists alone for more than 6 months. If add-back therapy is prescribed, the GnRH agonist may be prescribed for a longer period.

GnRH treatments can increase the risk for birth defects. Women who are taking GnRH agonists should use non-hormonal birth control methods, such as the diaphragm, cervical cap, or condoms while on the treatments.

Other Drug Treatments

Danazol

Danazol (Danocrine, generic) is a synthetic drug that resembles a male hormone (androgen). It suppresses the pathway leading to ovulation. Danazol is rarely used for endometriosis therapy nowadays. Many women stop taking this drug because of its adverse side effects, which include:

- Bloating

- Acne

- Irregular vaginal bleeding

- Muscle cramps

Danazol can also cause male characteristics, such as growth of facial hair, reduced breasts, and deepening of the voice. Because GnRH agonists cause far fewer side effects, danazol is not a first-line choice for endometriosis treatment.

Aromatase inhibitors

Aromatase inhibitors (AIs) are a class of drugs that stop the body from making estrogen in tissues such as fat and skin. However, these drugs do not prevent the ovaries from making estrogen. AIs are primarily used for more severe pain caused by endometriosis where other treatments have not worked, and include:

- Anastrozole (Arimidex)

- Letrozole (Femara)

- Exemestane (Aromasin)

Conservative Surgery

The goal of conservative surgery is to remove as many endometrial implants and cysts as possible without causing surgical scarring or subsequent adhesions that could cause fertility problems. Surgery can help improve fertility in women with severe endometriosis. Whether it offers any advantage in pregnancy rates in women with mild-to-moderate endometriosis is unclear. Conservative surgery can also help relieve pain caused by implants. It may, however, miss microscopic implants that could continue to cause pain and other symptoms after the procedure.

The two conservative surgical procedures are:

Laparoscopy.

This is the gold standard and most commonly performed surgical treatment for endometriosis. It involves making several small abdominal incisions through which a thin telescopic tube (laparoscope) is inserted. The doctor removes implants and scar tissue or destroys them with heat. Laparoscopy requires general anesthesia, but it is an outpatient procedure and the patient can go home the same day. Recovery usually takes a few weeks.Laparotomy.

This procedure uses a wide abdominal incision and conventional surgical instruments. It is much more invasive and requires a longer recovery time (typically several months). Laparotomy is rarely performed except in cases of severe endometriosis.

Laparoscopy Procedure

A laparoscopy is performed, usually under general anesthesia, as follows:

- Carbon dioxide gas is injected into the abdomen, distending it and pushing the bowel away so that the doctor has a wider view.

- The procedure requires making small incisions at the navel and above the pubic bone.

- The laparoscope (a narrow tube equipped with camera lenses and a fiber-optic light source) is inserted through the incision at the navel (the umbilical incision).

- A probe is then inserted through the second incision, allowing the doctor to directly view the outside surface of the uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries.

- One or two additional small incisions can be made on either side of the lower abdomen through these incisions. Surgical instruments or other devices are passed through these accessory incisions to destroy or remove abnormal tissue. Implants can be removed by excision (surgical removal) using a laser or scissors or by destroying the area with lasers or with electricity (or electrocautery).

Complications

People may experience temporary but severe discomfort in the shoulders after laparoscopy due to residual carbon dioxide gas that puts pressure on the diaphragm. The incisions, even with laparoscopy, may cause pain afterward, which can usually be treated effectively with mild pain relievers. There are small risks for bleeding, infection, and reaction to anesthesia.

Recurrence

Even with successful surgery, endometriosis may recur within several months to several years.

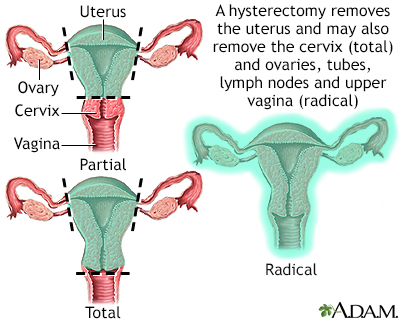

Hysterectomy

Hysterectomy is the surgical removal of the uterus. Removal of the uterus and ovaries is considered in women who do not respond well to conservative approaches and who do not wish to become pregnant. Endometriosis accounts for a significant percentage of hysterectomies. Hysterectomy does not, however, necessarily cure endometriosis.

A woman cannot become pregnant after having a hysterectomy. Women should realize that hysterectomy causes immediate menopause if the ovaries are also removed.

Types of Hysterectomies

Once a decision for a hysterectomy has been made, the patient should discuss with her doctor what will be removed. The common choices are:

Total Hysterectomy (Removal of uterus and cervix).

Removing only the uterus with hysterectomy has the same risk for recurrence as conservative surgery. Subtotal hysterectomy involves removing the uterus but keeping the cervix intact.Bilateral Oophorectomy (Removal of both ovaries)

orBilateral Salpingo-Oophorectomy (Removal of the fallopian tubes and ovaries).

For endometriosis treatment, removal of the ovaries is often performed in combination with hysterectomy.

Hysterectomy is surgical removal of the uterus, resulting in inability to become pregnant. This surgery may be done for a variety of reasons, including chronic pelvic inflammatory disease, uterine fibroids, and cancer. A hysterectomy may be done through an abdominal or a vaginal incision.

Removal of the ovaries (oophorectomy) along with hysterectomy significantly reduces the likelihood that endometriosis will recur. However, there is still a small chance that recurrence can happen.

Types of Hysterectomy Procedures

Hysterectomies may be performed abdominally (through an incision in the abdomen) or vaginally (through a vaginal incision). A variation of the vaginal approach is called laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH). There are other laparoscopic approaches as well, including total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) and robotic assisted laparoscopy. Recovery times for vaginal hysterectomy and laparoscopic procedures are shorter than those for abdominal hysterectomy.

After Hysterectomy

The ovaries are the main source of production of estrogen. In premenopausal women, the removal of both ovaries causes immediate menopause. After a hysterectomy with bilateral oophorectomy, women may have hot flashes and other symptoms of menopause, including vaginal dryness, insomnia, and weight gain. Prescribed hormone replacement will typically ameliorate these symptoms. Women who have surgical removal of both ovaries, and who do not receive hormone replacement therapy, tend to have more severe hot flashes than women who enter menopause naturally. The lack of estrogen is also associated with increased risk for cardiovascular and metabolic diseases.

If hormone therapy is recommended after hysterectomy, it is given as estrogen-only therapy (ET). Women who do not have a uterus do not need to take combination estrogen-progesterone therapy.

After a total hysterectomy, in which the cervix has been removed, a woman may not need annual Pap smears of the cervix depending on her medical/gynecological history. However, she still should get regular pelvic and breast exams.

Resources

- American Society for Reproductive Medicine -- www.asrm.org

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists -- www.acog.org

- National Women's Health Information Center -- www.womenshealth.gov

- Global forum for news and information -- endometriosis.org

- National Infertility Association -- resolve.org

References

Advincula A, Truong M, Lobo RA. Endometriosis: etiology, pathology, diagnosis, management. In: Lobo RA, Gershenson DM, Lentz GM, Valea FA, eds. Comprehensive Gynecology. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017:chap 19.

Angioni S, Pontis A, Dessole M, Surico D, De Cicco Nardone C, Melis I. Pain control and quality of life after laparoscopic enblock resection of deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) vs. incomplete surgical treatment with or without GnRHa administration after surgery. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;291(2):363-370. PMID: 25151027 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25151027/.

Brown J, Farquhar C. An overview of treatments for endometriosis. JAMA. 2015;313(3):296-297. PMID: 25603001 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25603001/.

Brown J, Crawford TJ, Datta S, Prentice A. Oral contraceptives for pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;5:CD001019. PMID: 29786828 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29786828/.

Bulun SE, Yilmaz BD, Sison C, Miyazaki K, Bernardi L, Liu S, Kohlmeier A, Yin P, Milad M, Wei J. Endometriosis. Endocr Rev. 2019;40(4):1048-1079. PMID: 30994890 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30994890/.

Burney RO, Guidice LC. Endometriosis. In: Jameson JL, De Groot LJ, de Kretser DM, et al, eds. Endocrinology: Adult and Pediatric. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2016:chap 130.

Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, Berry-Bibee E, Horton LG, Zapata LB, Simmons KB, Pagano HP, Jamieson DJ, Whiteman MK. U.S. Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(3):1-103. PMID: 27467196 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27467196/.

DiVasta AD, Feldman HA, Sadler Gallagher J, et al. Hormonal add-back therapy for females treated with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist for endometriosis: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(3):617-627. PMID: 26181088 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26181088/.

Dowlut-McElroy T, Strickland JL. Endometriosis in adolescents. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2017;29(5):306-309. PMID: 28777193 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28777193/.

Dunselman GA, Vermeulen N, Becker C, et al. ESHRE guideline: management of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(3):400-412. PMID: 24435778 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24435778/.

Fu J, Song H, Zhou M, et al. Progesterone receptor modulators for endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;7:CD009881. PMID: 28742263 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28742263/.

Granese R, Perino A, Calagna G, et al. Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone analogue or dienogest plus estradiol valerate to prevent pain recurrence after laparoscopic surgery for endometriosis: a multi-center randomized trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;94(6):637-645. PMID: 25761587 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25761587/.

Liu E, Nisenblat V, Farquhar C, et al. Urinary biomarkers for the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(12):CD012019. PMID: 26695425 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26695425/.

Muzii L, Di Tucci C, Achilli C, et al. Continuous versus cyclic oral contraceptives after laparoscopic excision of ovarian endometriomas: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(2):203-211. PMID: 26364832 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26364832/.

Nisenblat V, Bossuyt PM, Farquhar C, Johnson N, Hull ML. Imaging modalities for the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2:CD009591. PMID: 26919512 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26919512/.

Nisenblat V, Bossuyt PM, Shaikh R, et al. Blood biomarkers for the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(5):CD012179. PMID: 27132058 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27132058/.

Osayande AS, Mehulic S. Diagnosis and initial management of dysmenorrhea. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89(5):341-346. PMID: 24695505 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24695505/.

Parasar P, Ozcan P, Terry KL. Endometriosis: epidemiology, diagnosis and clinical management. Curr Obstet Gynecol Rep. 2017;6(1):34-41. PMID: 29276652 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29276652/.

Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Treatment of pelvic pain associated with endometriosis: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(4):927-935. PMID: 24630080 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24630080/.

Schrager S, Falleroni J, Edgoose J. Evaluation and treatment of endometriosis. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87(2):107-113. PMID: 23317074 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23317074/.

Speer LM, Mushkbar S, Erbele T. Chronic pelvic pain in women. Am Fam Physician. 2016;93(5):380-387. PMID: 26926975 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26926975/.

Stout A, Jeve Y. The management of endometriosis-related pelvic pain. Obstetrics, Gynaecology and Reproductive Medicine. 2021. doi.org/10.1016/j.ogrm.2021.01.005.

Taylor HS, Kotlyar AM, Flores VA. Endometriosis is a chronic systemic disease: clinical challenges and novel innovations. Lancet. 2021;397(10276):839-852. PMID: 33640070 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33640070/.

Zondervan KT, Becker CM, Missmer SA. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(13):1244-1256. PMID: 32212520 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32212520/.

|

Review Date:

3/28/2021 Reviewed By: John D. Jacobson, MD, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Loma Linda University School of Medicine, Loma Linda, CA. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team. |