Uterine fibroids and hysterectomy - InDepth

Highlights

Uterine Fibroids

Uterine fibroids, also called uterine leimyomas or myomas, are non-cancerous growths that originate in the muscular wall of the uterus. Fibroids are the most common type of tumor found in female reproductive organs.

Symptoms of Uterine Fibroids

Many women with fibroids do not have any symptoms. When symptoms do occur, they may include:

- Heavy and prolonged menstrual bleeding

- Painful menstrual periods

- Pressure and pain in the abdomen and lower back

- Bloated and swollen abdomen

- Frequent urination

- Constipation

- Pain during intercourse

When occurring during pregnancy, fibroids may give rise to complications such as miscarriage, preterm birth, or postpartum hemorrhage.

Treatment

Women without symptoms do not need treatment, but they should be evaluated regularly by their doctors. Women with symptoms from their fibroids have many options for treatment, including drugs and surgery. Several of these treatment options impact a woman's chances of becoming pregnant.

Fibroids usually shrink after menopause, so many women close to menopause (average age 51 to 52) choose to defer treatment. This, however, is a slow process and it should not be assumed that very large fibroids will shrink away quickly after menopause.

Introduction

A uterine fibroid (known medically as a

leiomyoma

ormyoma

) is a noncancerous (benign) growth of smooth muscle and connective tissue. Fibroids can range in size from as small as a pinhead to larger than a melon. Fibroids have been reported weighing more than 40 pounds.Fibroids originate from the thick wall of the uterus and are categorized by where they grow:

Intramural fibroids.

Grow within the middle and thickest layer of the uterus (called themyometrium

).Subserosal fibroids.

Grow out from the thin outer fibrous layer of the uterus (called theserosa

). Subserosal can be either stalk-like (pedunculated

) or broad-based (sessile

).Submucosal fibroids.

Grow from the uterine wall toward and into the inner lining of the uterus (theendometrium

). Submucosal fibroids can also be stalk-like or broad-based.

Fibroid tumors may not need to be removed if they are not causing pain, bleeding excessively, or growing rapidly.

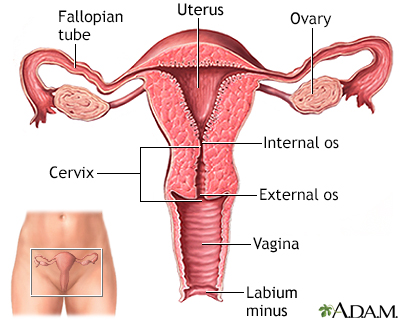

The Female Reproductive System

The primary structures in the reproductive system include:

- The

uterus

is a pear-shaped organ located between the bladder and lower intestine. It consists of two parts, the body and the cervix. - When a woman is not pregnant the

body

of the uterus is about the size of a fist, with its walls pressed against each other. During pregnancy the walls of the uterus are pushed apart as the fetus grows. - The

cervix

is the lower portion of the uterus. It has a canal opening into the vagina with an opening called theos

, which allows menstrual blood to flow out of the uterus into the vagina. It is the os that dilates allowing birth of a child. - Leading off each side of the body of the uterus are two tubes known as the fallopian tubes. Near the end of each tube is an ovary.

- Ovaries are egg-producing organs that hold 200,000 to 400,000 follicles (from folliculus, meaning "sack" in Latin). These cellular sacks contain the materials needed to produce ripened eggs, or ova.

The inner lining of the uterus is called the

endometrium

. During pregnancy this inner lining thickens and becomes enriched with blood vessels to house and support the growing fetus. If pregnancy does not occur, the endometrium is shed as part of the menstrual flow. Menstrual flow also consists of blood and mucus from the cervix and vagina.Reproductive Hormones

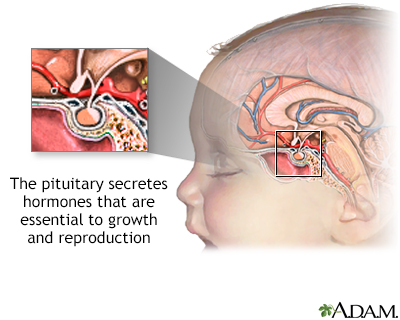

The

hypothalamus

(an area in the brain) and thepituitary gland

regulate the reproductive hormones. The pituitary gland is often referred to as the master gland because of its important role in many vital functions, many of which require hormones.In women, six key hormones serve as chemical messengers that regulate the reproductive system:

- The hypothalamus first releases

gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH)

. - This chemical, in turn, stimulates the pituitary gland to produce

follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)

andluteinizing hormone (LH)

. Estrogen

,progesterone

, and the male hormonetestosterone

are secreted by the ovaries at the command of FSH and LH and complete the hormonal group necessary for reproductive health.

It is not clear what causes fibroids, but estrogen and progesterone appear to play a major role in their growth. Fibroids tend to shrink after menopause, when estrogen levels decline.

Risk Factors

Uterine fibroids are the most common tumor found in female reproductive organs.

Age

Fibroids are most common in women from their 30s through early 50s. (After menopause, fibroids tend to shrink.) About 20% to 40% of women age 35 and older have fibroids of significant enough size to cause symptoms.

Race and Ethnicity

Uterine fibroids are particularly common in African American women, and these women tend to develop them at a younger age than white women. Fibroids in African American women are usually larger at the time of diagnosis than those in white women, and tend to cause more severe symptoms.

Family History

Family history (having a mother or sister who had fibroids) may increase risk.

Other Possible Risk Factors

Obesity and high blood pressure may be associated with increased fibroid risk. Low vitamin D levels also appear to be associated with an increased risk of uterine fibroids.

Complications

Effect on Fertility

Most fibroids appear to have only a small effect on a woman's fertility. Female infertility is usually due to other factors than fibroids.

Effect on Pregnancy

Fibroids may increase pregnancy complications and delivery risks. These may include:

- Cesarean section delivery due to problems during labor. The cesarean section may be complicated by having to work around the fibroids in the uterine wall.

- Breech presentation (baby enters the birth canal upside down with feet or buttocks emerging first).

- Preterm birth and miscarriage.

- Placenta previa (placenta covers the cervix).

- Excessive bleeding after giving birth (postpartum hemorrhage).

Anemia

Anemia due to iron deficiency can develop if fibroids cause excessive bleeding. Small, submucosal fibroids are most likely to cause abnormally heavy bleeding.

Most cases of anemia are mild and can be treated with dietary changes and iron supplements. However, prolonged and severe anemia that is not treated can cause heart problems.

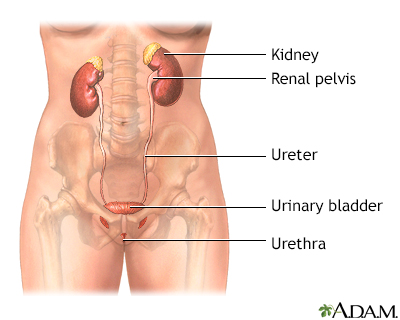

Urinary and Bowel Problems

Fibroids can press and squeeze the bladder, leading to frequent need for urination.

Large fibroids that press against the bladder occasionally result in urinary tract infections. If the urethra (bladder outlet) is pressured or blocked, urinary retention may occur. Pressure on the ureters may cause urinary tract obstruction and kidney damage.

Pressure on the bowels may result in constipation.

Uterine (Endometrial) Cancer

Any fibroid has the rare potential to be cancerous (malignant). However, the vast majority of fibroids are noncancerous (benign). Fibroids after menopause have the highest risk of being cancerous, especially if they are continuing to grow. Women who are postmenopausal need to have careful monitoring of their fibroids. Doctors often recommend removing any growing fibroid after menopause.

Symptoms

Many women with fibroids do not have symptoms. When they do, symptoms may include:

Heavy Menstrual Bleeding.

The most common symptom is prolonged and heavy bleeding during menstruation. This is caused by fibroid growth bordering the uterine cavity. Menstrual periods may also last longer than normal.Menstrual Pain.

Heavy bleeding and clots can cause severe cramping and pain during menstrual periods.Abdominal Pressure and Pain.

Large fibroids can cause pressure and pain in the abdomen or lower back that sometimes feels like menstrual crampsAbdominal and Uterine Enlargement.

As the fibroids grow larger, some women feel them as hard lumps in the lower abdomen. Very large fibroids may give the abdomen the appearance of pregnancy and cause a feeling of heaviness and pressure. In fact, large fibroids are defined by comparing the size of the uterus to the size it would be at specific months during gestation.Pain During Intercourse.

Fibroids can cause pain during sexual intercourse (dyspareunia) and on occasion may actually prevent penetration.Urinary Problems.

Large fibroids may press against the bladder and urinary tract and cause frequent urination or the urge to urinate, particularly when a woman is lying down at night. Fibroids pressing on the ureters (the tubes going from the kidneys to the bladder) may obstruct or block the flow of urine. Fibroids pressing on the urethra (outlet of the bladder) may cause urinary retention.Constipation.

Fibroid pressure against the rectum can cause constipation.

Diagnosis

Pelvic Exam and Medical History

Doctors can detect some fibroids as masses (lumps) during a pelvic exam. During a pelvic exam, the doctor will check for pregnancy-related conditions and other conditions, such as ovarian cysts. The doctor will ask you about your medical history, particularly as it relates to menstrual bleeding patterns. Other causes of abnormal uterine bleeding must also be considered.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is the standard imaging technique for detecting uterine fibroids. The doctor will order transabdominal and transvaginal ultrasounds. Ultrasound is a painless technique that uses sound waves to image the uterus and ovaries. In transabdominal ultrasound, the ultrasound probe is moved over the abdominal area. In transvaginal ultrasound, the probe is inserted into the vagina.

A variation of ultrasound, called hysterosonography, uses ultrasound along with saline (salt water) infused into the uterus to enhance the visualization of the uterus.

Hysteroscopy

Hysteroscopy is a procedure that may be used to detect the presence of fibroids, polyps, or other causes of bleeding originating from the inside of the uterine cavity. It may also be used during surgical procedures to remove fibroids.

Hysteroscopy can be performed in a doctor's office or in a hospital setting. The procedure uses a long flexible tube called a hysteroscope, which is inserted into the vagina and through the cervix to reach the uterus. A fiber-optic light source and a tiny camera in the tube allow the doctor to view the cavity. The uterus is filled with saline or carbon dioxide to inflate the cavity and provide better viewing. This can cause cramping.

Hysteroscopy is minimally invasive and does not require incisions. Local, regional, or general anesthesia is typically given.

Laparoscopy

In some cases, laparoscopic surgery may be performed as a diagnostic procedure. Laparoscopy involves inserting a fiber-optic scope into a small incision made near the navel, into the abdomen. Whereas hysteroscopy allows the doctor to view inside the uterus, laparoscopy provides a view of the outside of the uterus, including the ovaries, fallopian tubes, and general pelvic area and the rest of the abdomen.

Other Tests

In certain cases, the doctor may perform an endometrial biopsy to determine if there are abnormal cells in the lining of the uterus that suggest cancer. Endometrial biopsy can be performed in a doctor's office, with or without anesthesia. Dilation & curettage (D&C) is a more invasive procedure that involves scraping the inside lining of the uterus. It can be used to take tissue samples and can help temporarily reduce heavy menstrual bleeding. This may frequently be combined with hysteroscopy.

The doctor may also order a complete blood count (CBC) to check for signs of anemia.

Ruling out Other Conditions that Cause Heavy Bleeding

Almost all women, at some time in their reproductive life, experience heavy bleeding during menstrual periods.

A number of conditions can cause or contribute to the risk:

- Menstrual disorders

- Miscarriage

- Having late periods or approaching menopause

- Uterine polyps (small benign growths in the uterus)

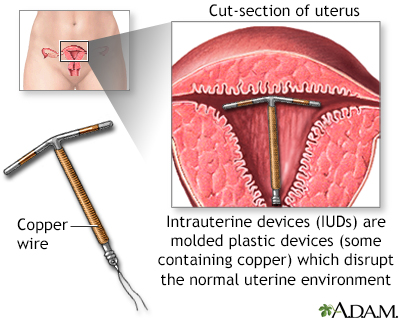

- Copper intrauterine device (IUD) contraceptive

The intrauterine device (IUD) shown uses copper as the active contraceptive; others use progesterone in a plastic device.

- Bleeding disorders that impair blood clotting, Von Willebrand disease, some coagulation factor deficiencies, or leukemia.

- Uterine cancer.

- Pelvic infections.

- Adenomyosis. This condition occurs when glands from the uterine lining become embedded in the uterine muscle. Its symptoms are similar to fibroids, but there is usually more pain with adenomyosis.

- Medical conditions, including thyroid problems and systemic lupus erythematosus.

- Certain drugs, including anticoagulants and anti-inflammatory medications.

- Often, the cause of heavy bleeding is unknown.

Treatment

Many women with uterine fibroids do not require treatment. A woman's age and the severity of her symptoms are important factors in considering treatment options.

The three treatment options are:

Watchful Waiting.

A woman may choose to delay having any treatment, particularly if she is close to reaching menopause. Periodic pelvic exams and ultrasounds can help track the progression of her fibroid condition.Drug Therapy.

Hormonal treatments such as oral contraceptives or a progestin-releasing IUD can help reduce heavy bleeding and pain. Gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists stop ovulation and the production of estrogen, and can reduce fibroid size.Surgery.

There are many surgical options ranging from less invasive to very invasive. They include removal of the fibroid (myomectomy), removal of the endometrial lining (endometrial ablation), shrinking the blood supply to the fibroid (uterine artery embolization), and removal of the uterus (hysterectomy).

Women should discuss each option with their doctor. Deciding on a particular surgical procedure depends on the location, size, and number of fibroids. Certain procedures affect a woman's fertility and are recommended only for women who are past childbearing age or who do not want to become pregnant. In terms of surgical options, myomectomy is generally the only commonly performed procedure that preserves fertility.

Medications

For fibroid pain relief, women can use acetaminophen (Tylenol, generic) or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) such as ibuprofen (Motrin, Advil, generic) or naproxen (Aleve, generic).

Prescription drug treatment of fibroids uses medicines that block or suppress estrogen, progesterone, or both hormones.

Hormonal Contraceptives

Oral contraceptives (OCs) are sometimes used to control the heavy menstrual bleeding associated with fibroids, but they do not reduce fibroid growth. Newer types of continuous-dosing OCs reduce or eliminate the number of periods a woman has per year.

Intrauterine devices (IUDs) that release progestin can help reduce heavy bleeding. Specifically, the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system, or LNG-IUS (Mirena), has shown excellent results. It is approved by the FDA to treat heavy menstrual bleeding. However, in rare cases the presence of fibroids may cause the IUD to be expelled from the uterus.

GnRH Agonists

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists include the implant goserelin (Zoladex), a monthly injection of leuprolide (Lupron Depot, generic), and the nasal spray nafarelin (Synarel). GnRH agonists block the release of the reproductive hormones LH (luteinizing hormone) and FSH (follicle-stimulating hormone). As a result, the ovaries stop ovulating and producing estrogen. Basically, GnRH agonists induce a temporary menopause.

GnRH agonists may be used as drug treatment to shrink fibroids in women who are approaching the age of menopause. They may also be used as a preoperative treatment 3 to 4 months before fibroid surgery to reduce fibroid size so that a more minimally invasive surgical procedure can be performed.

Commonly reported side effects, which can be severe in some women, include menopausal-like symptoms. These symptoms include:

- Hot flashes

- Night sweats

- Vaginal dryness

- Weight gain

- Depression

- Mood changes

The side effects vary in intensity, but typically resolve within 1 month after stopping the medication.

The most important concern is possible osteoporosis from estrogen loss. Women should not take these drugs for more than 6 months. It may be possible to extend treatment with GnRH agonists if low dose treatment with estrogen and progesterone is administered (add-back therapy). Talk to your provider about this possibility.

GnRH treatments used alone do not prevent pregnancy. Furthermore, if a woman becomes pregnant during their use, there is some risk for birth defects.

Surgical Alternatives to Hysterectomy

Myomectomy

A myomectomy surgically removes only the fibroids and leaves the uterus intact, which helps preserve fertility. Myomectomy may also help regulate abnormal uterine bleeding caused by fibroids. Not all women are candidates for myomectomy. If the fibroids are numerous or large, myomectomy can become complicated, resulting in increased blood loss. If cancer is found, conversion to a full hysterectomy may be necessary.

To perform a myomectomy, the surgeon may use a standard "open" surgical approach (laparotomy) or less invasive ones (hysteroscopy or laparoscopy).

Laparotomy.

Laparotomy uses a normal abdominal incision and conventional "open" surgery. It is used for subserosal or intramural fibroids that are very large (usually more than 4 inches), numerous, and are in a difficult area of the uterus to approach surgically, or when cancer is suspected. While complete recovery takes less than a week with laparoscopy and hysteroscopy, recovery from a standard abdominal myomectomy takes as long as 6 to 8 weeks. Open laparotomy poses a higher risk for scarring and blood loss than with the less invasive procedures, a concern for women who want to retain fertility.Hysteroscopy.

A hysteroscopic myomectomy may be used for submucosal fibroids found in the uterine cavity. With this procedure, fibroids are removed using an instrument called a hysteroscopic resectoscope, which is passed up into the uterine cavity through the vagina and cervical canal. The doctor then uses an electrosurgical wire loop to surgically remove (resect) the fibroid.Laparoscopy.

Women whose uterus is no larger than it would be at a 12 to 14 week pregnancy and who have a small number of subserosal fibroids may be eligible for treatment with laparoscopy. As with hysteroscopy, thin scopes are used that contain surgical and viewing instruments. Laparoscopy requires only tiny incisions, and has a much faster recovery time than laparotomy.

Complications

The risks for myomectomy are generally the same as those for other surgical procedures, including bleeding, infection, or injury to other areas.

Laparoscopic power morcellation is a procedure that uses a tool to cut up uterine fibroids into tiny pieces to be removed through a small incision in the abdomen. There is evidence that power morcellation may spread cancerous tissue in women with fibroids undergoing this procedure who have undetected uterine cancer. The FDA and other expert groups advise against the use of laparoscopic power morcellators for myomectomy or hysterectomy procedures.

Recurrence of Fibroids

Myomectomy is not necessarily a permanent solution for fibroids. They can recur after these procedures. Hence in general, myomectomy is used if fertility preservation is required, and hysterectomy is used if child bearing is complete to avoid the possibility of having to do a second procedure if fibroids grow back.

Uterine Artery Embolization

Uterine artery embolization (UAE), also called uterine fibroid embolization (UFE), is a relatively new way of treating fibroids. UAE deprives fibroids of their blood supply, causing them to shrink.

UAE is a minimally invasive radiology treatment and is technically a nonsurgical therapy. It is less invasive than hysterectomy and myomectomy, and involves a shorter recovery time than the other procedures. The patient remains conscious, although sedated, during the procedure, which takes around 60 to 90 minutes.

The procedure is typically performed in the following manner:

- The patient receives a sedative to cause drowsiness, and a local anesthetic is applied to the skin around the groin.

- An interventional radiologist makes a small quarter-inch incision in the skin and inserts a catheter (a thin tube) into the femoral artery. The femoral artery is a large artery that begins in the lower abdomen and extends down to the thigh. The radiologist then threads the catheter into the uterine artery.

- Small plastic particles are injected into the artery. These particles block the blood supply to the tiny arteries that feed fibroid cells, and the tissue eventually dies.

- Patients usually stay in the hospital overnight after UAE and are given pain medication. Pelvic cramps are common for the first 24 hours after the procedure.

- It takes 1 to 2 weeks for the patient to recover from the procedure and return to work. It may take several months to several years for the fibroids to completely shrink.

- Most patients have a light, brownish color vaginal discharge for several days following UAE, which may last until the next menstrual cycle. Most women resume regular menstrual cycles within 2 to 3 months of the procedure. Heavy menstrual bleeding reduced by the second or third cycle.

Effect on Fertility

In general, UAE is considered an option for only those who have completed childbearing. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists advises women who wish to have children that it is not yet known how this procedure affects their potential for becoming pregnant.

Complications

Compared to other procedures, women who have UAE miss fewer days of work. Serious complications occur in less than 0.5% of cases. In addition to potential impact on fertility, other postoperative effects may include.

Pain.

Abdominal cramps and pelvic pain after the procedure are nearly universal and may be intense. Pain usually begins soon after the procedure and typically plateaus by 6 hours. The pain usually improves each day over the next several days. A low-grade fever and general malaise are also common in the first week after the procedure.Early menopause.

Most women who have UAE will continue to have normal menstrual periods. Some women, however, go through menopause after the procedure. Menopause is more likely to occur in women over age 45 that have UAE.

Success Rates

Uterine artery embolization is very effective and most women are very satisfied with the results. Menorrhagia symptoms, as well as pelvic pain and urinary symptoms, improve in 85% to 95% of women within 3 months after treatment. However, some women may have fibroid recurrence and may need future procedures (repeat embolization or hysterectomy).

Some studies suggest that women with larger single fibroids or larger uteruses are not good candidates for UAE. Pedunculated fibroids are usually not treated with UAE due to the risk of severe pain in this setting following the procedure.

Uterine artery embolization does not remove fibroid tissue. In the rare cases of sarcoma (cancer cells in the muscles of the uterus), this procedure may delay diagnosis and therefore worsen prognosis.

Endometrial Ablation

Endometrial ablation destroys the lining of the uterus (the endometrium) and is usually performed to stop heavy menstrual bleeding. It may also be used to treat women with small fibroids. It is not helpful for large fibroids or for fibroids that have grown outside of the interior uterine lining. For most women, this procedure stops the monthly menstrual flow. In some women, menstrual flow is not stopped but is significantly reduced.

Most endometrial ablation procedures use some form of heat (radiofrequency, heated fluid, microwaves) to destroy the uterine lining. The procedure is typically done on an outpatient basis and can take as few as 10 minutes to perform. Recovery generally takes a few days, although watery or bloody discharge can last for several weeks.

Endometrial ablation significantly decreases the likelihood a woman will become pregnant. However, pregnancy can still occur and this procedure increases the risks of complications, including miscarriage and ectopic (tubal) pregnancies. Women who have this procedure must be committed to not becoming pregnant and to using birth control.

A main concern of endometrial ablation is that it may delay or make it more difficult to diagnose uterine cancer in the future. (Postmenopausal bleeding or irregular vaginal bleeding can be warning signs of uterine cancer.) Women who have endometrial ablation still have a uterus and cervix, and should continue to have recommended Pap smears and pelvic exams.

Magnetic Resonance Guided Focused Ultrasound (MRgFUS)

MRgFUS is a non-invasive procedure that uses high-intensity ultrasound waves to heat and destroy (ablate) uterine fibroids. This "thermal ablation" procedure is performed with a device, the ExAblate, which combines magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with ultrasound.

During the 3-hour procedure, the patient lies inside an MRI machine. The patient receives a mild sedative to help relax but remains conscious throughout the procedure. The radiologist uses the MRI to target the fibroid tissue and direct the ultrasound beam. The MRI also helps the radiologist monitor the temperature generated by the ultrasound.

MRgFUS is appropriate only for women who have completed childbearing or who do not intend to become pregnant. The procedure cannot treat all types of fibroids. Fibroids that are located near the bowel and bladder, or outside of the imaging area, cannot be treated.

This procedure is relatively new, and long-term results are not yet available. Likewise, it requires an extensive period of time involving MRI equipment. Many insurance companies consider this procedure investigational, experimental, and unproven and do not pay for this treatment. Currently available evidence suggests that the procedure is moderately effective, however UAE may be more effective, with fewer treatment failures and subsequent need for a second procedure.

Ultrasound Guided Radiofrequency Ablation

This is a minimally invasive laparoscopic procedure that uses high energy waves to generate heat that destroys fibroids. Ultrasound is used to verify the correct placement of the radiofrequency device within each fibroid before ablation is performed. The procedure is usually performed on an outpatient basis and is considered a safe and relatively low risk alternative to hysterectomy.

Hysterectomy

Hysterectomy is the surgical removal of the uterus. The ovaries may also be removed, although this is not necessary for fibroid treatment. Hysterectomy is a permanent solution for fibroids, and is an option if other treatments have not worked or are not appropriate.

A woman cannot become pregnant after having a hysterectomy. If the ovaries are removed along with the uterus, hysterectomy causes immediate menopause.

Types of Hysterectomies

Once a decision for a hysterectomy has been made, the patient should discuss with her doctor what will be removed. The common choices are:

- Total hysterectomy (removal of uterus and cervix).

- Subtotal, also called supracervical hysterectomy (removal of uterus with preservation of the cervix).

- Oophorectomy (removal of an ovary). Bilateral oophorectomy is the removal of both ovaries. Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is the removal of the fallopian tubes and ovaries). These procedures can be performed with either total or supracervical hysterectomy.

Types of Hysterectomy Procedures

Hysterectomy procedures include:

- Abdominal hysterectomy

- Vaginal hysterectomy

- Laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH)

- Total laparoscopic hysterectomy

- Robotic-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy

Total Abdominal Hysterectomy

Total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH) has been the traditional procedure. It is an invasive procedure that is best suited for women with large fibroids, when the ovaries also need to be removed, or when cancer or pelvic disease is present.

The surgeon makes a 5- to 7-inch incision in the lower part of the belly. The cut may either be vertical, or it may go horizontally across the abdomen, just above the pubic hair (a bikini cut). The bikini cut incision heals faster and is less noticeable than a vertical incision, which is used in more complicated cases or with very large fibroids. The patient may need to remain in the hospital for 3 to 4 days, and recuperation at home takes about 4 to 6 weeks.

Vaginal Hysterectomy

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends vaginal hysterectomy as the first choice, when possible. Vaginal hysterectomy requires only a vaginal incision through which the uterus is removed. The vaginal incision is closed with stitches.

LAVH, and Total Laparoscopic Hysterectomy

Newer minimally invasive procedures have become the preferred methods for hysterectomy. ACOG recommends laparoscopic hysterectomy as the second choice for minimally invasive procedures. Laparoscopic hysterectomies use a laparoscope to help guide and perform the surgery, and allows the ovaries to be easily removed at the same time. The laparoscope is a thin flexible tube through which a tiny video camera and surgical instruments are inserted.

A variation of the vaginal approach is called laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH). It uses several small abdominal incisions through which the surgeon severs the attachments to the uterus and, if needed, ovaries. In LAVH, part of the procedure is completed vaginally, as in the standard vaginal approach. In total laparoscopic hysterectomy, the entire procedure is performed via laparoscopy, with the uterus either removed through the vagina or placed in a plastic bag and broken up into small pieces so it can be removed via the small laparoscopic incisions. The FDA discourages the use of laparoscopic power morcellation with hysterectomy (see below in "Complications".)

Vaginal hysterectomy, LAVH, total laparoscopic hysterectomy, and robotic-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy may have fewer complications, shorter hospital stays, and faster recovery times than abdominal hysterectomy.

Robotic Hysterectomy

Robotic-assisted hysterectomy is a type of laparoscopic hysterectomy, but the surgical instruments are attached to a robot. The surgeon uses a computer console in the operating room to guide the robot's movements.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) advises that robotic hysterectomy is best suited for complex hysterectomies. Before choosing robotic hysterectomy, it is important to find a surgeon who has extensive training and experience with this technique.

Complications

Minor complications after hysterectomy are very common. Many women develop minor and treatable urinary tract infections. There is usually mild pain and light vaginal bleeding post operation. More serious complications are uncommon but can include infection, blood clots, or injury to adjacent organs.

Power Morcellation

Laparoscopic power morcellation is a procedure that is sometimes used during laparoscopic hysterectomy or myomectomy. The power morcellator is a rapidly spinning cutting device that breaks up the uterus into smaller fragments that can be removed through small abdominal incisions. It can push many of these small pieces of the uterus throughout the abdominal cavity.

In 2014, the FDA discouraged the use of laparoscopic power morcellation because of evidence that this procedure can spread cancer through the pelvis and abdomen in women who have undetected uterine sarcoma, a type of uterine cancer. As many as 1 in 350 women who undergo hysterectomy or myomectomy for uterine fibroids have this type of cancer. A black box warning was required on all product labels and several of these devices have been withdrawn from the market since. With even more evidence on the risk of spreading cancer, in 2017 the FDA reaffirmed its 2014 decision.

Power morcellators should never be used in women who are peri- or post-menopausal, or in women who have suspected or known uterine cancer. Younger women who are considering a fibroid procedure using power morcellation should discuss with their doctors all possible risks.

Postoperative Care

Ask a family member or friend to help out for the first few days at home. The following are some of the precautions and tips for postoperative care:

- For 1 to 2 days after surgery, you will be given medications to prevent nausea and painkillers to relieve pain at the incision site.

- As soon as the doctor recommends it, usually within a day of the operation, you should get up and walk in order to help prevent pneumonia, reduce the risk of blood-clot formation, and speed recovery.

- Walking and slow, deep breathing exercises may help to relieve gas pains, which can cause major discomfort for the first few days.

- Coughing can cause pain, which may be reduced by holding a pillow over a surgical abdominal wound or by crossing the legs after vaginal surgery.

- Do not lift heavy objects, douche or take baths, climb stairs or drive for several weeks following surgery.

- Discuss with your surgeon when you will be able to have sex after the procedure. The vaginal incision is the weakest part of the surgery and needs to heal completely before being tested.

Women who have had abdominal hysterectomies should discuss with their doctors when exercise programs more intense than walking can be started. The abdominal muscles are important for supporting the upper body, and recovering strength may take a long time. Even after the wound has healed, the patient may have an on-going feeling of overall weakness, for some time. Some women do not feel completely well for as long as a year while others may recover in only a few weeks.

If a woman has had her cervix removed, she no longer needs annual Pap smears, unless she has had a prior history of abnormal Pap testing, or had cancer found at the surgery. However, women who have had any type of hysterectomy should continue to receive routine pelvic and breast exams, and mammograms.

Premature Menopause after Hysterectomy

Surgical removal of the ovaries causes immediate menopause. If the ovaries are not removed, they will usually continue to secrete hormones until the natural age of menopause (average age 51 to 52 years), even after the uterus is removed.

Because hysterectomy removes the uterus, a woman will no longer experience menstrual periods, even if she has not become menopausal. Studies show that women who have had hysterectomies become menopausal on average 1 to 3 years earlier than would naturally occur.

Your doctor may recommend you take hormone therapy (HT) after your hysterectomy. Women who have had a hysterectomy are given estrogen-only therapy (ET), which may be administered as pills or as a skin patch that releases the hormone into the bloodstream. It can also be given locally to treat specific symptoms such as vaginal dryness (see below). Hot flashes and vaginal dryness are the most common menopausal symptoms. Hot flashes are often more severe after surgical menopause than in menopause that occurs naturally.

Sexuality after Hysterectomy

Sexual intercourse may resume 6 to 12 weeks following surgery. The effect of hysterectomy on sexuality varies among women. Most studies show no negative impact on sexuality after hysterectomy. A small percentage of women notice a negative impact on their sex drive or response. Other women report increased sexual drive and pleasure because they are free from the problems that prompted hysterectomy.

A vaginal lubricant can help reduce vaginal dryness.Vaginal moisturizing agents are available over the counter and may be effective. Dryness may be more of an issue due to loss of the cervical mucus. In studies done on the subject, a low-dose vaginal estrogen treatment applied directly into the vagina is the most effective treatment for vaginal dryness. It will need to be prescribed by your doctor. Topical vaginal estrogen is available in a cream, tablet, or ring that is inserted into the vagina.

Resources

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists -- www.acog.org

- American Society for Reproductive Medicine -- www.asrm.org

- Society of Interventional Radiology -- www.sirweb.org

- Radiology info from the American College of Radiology and the Radiological Society of North America -- www.radiologyinfo.org

- National Women's Health Information Center -- www.womenshealth.gov

References

Allen RH, Kaunitz AM, Hickey M. Hormonal contraception. In: Melmed S, Polonsky, KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM, eds. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 13th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:chap 18.

American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists website. Robotic surgery in gynecology. www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2015/03/robotic-surgery-in-gynecology. Updated March 2015. Accessed March 24, 2020.

Bartels CB, Cayton KC, Chuong FS, et al. An evidence-based approach to the medical management of fibroids: a systematic review. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2016;59(1):30-52. PMID: 26756261 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26756261.

Bulun SE. Physiology and pathology of the female reproductive axis. In: Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM, eds. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 13th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:chap 17.

Chittawar PB, Kamath MS. Review of nonsurgical/minimally invasive treatments and open myomectomy for uterine fibroids. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2015;27(6):391-397. PMID: 26536205 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26536205.

Dolan MS, Hill C, Valea FA. Benign gynecologic lesions: vulva, vagina, cervix, uterus, oviduct, ovary, ultrasound imaging of pelvic structures. In: Lobo RA, Gershenson DM, Lentz GM, Valea FA, eds. Comprehensive Gynecology. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017:chap 18.

Donnez J, Dolmans MM. Uterine fibroid management: from the present to the future. Hum Reprod Update. 2016;22(6):665-686. PMID: 27466209 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27466209.

Giannubilo SR, Ciavattini A, Petraglia F, Castellucci M, Ciarmela P. Management of fibroids in perimenopausal women. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2015;27(6):416-421. PMID: 26536206 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26536206.

Gupta JK, Sinha A, Lumsden MA, Hickey M. Uterine artery embolization for symptomatic uterine fibroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(5):CD005073. PMID: 22592701 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22592701.

Keung JJ, Spies JB, Caridi TM. Uterine artery embolization: A review of current concepts. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;46:66-73. PMID: 29128204 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29128204.

Kho KA, Brown DN. Surgical treatment of uterine fibroids within a containment system and without power morcellation. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2016;59(1):85-92. PMID: 26670832 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26670832.

Kho KA, Nezhat CH. Evaluating the risks of electric uterine morcellation. JAMA. 2014;311(9):905-906. PMID: 24504415 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24504415.

Laughlin-Tommaso S, Barnard EP, AbdElmagied AM, et al. FIRSTT study: randomized controlled trial of uterine artery embolization vs focused ultrasound surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220(2):174.e1-174.e13. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30696556.

Moravek MB, Bulun SE. Uterine fibroids. In: Jameson JL, De Groot LJ, de Kretser DM, et al, eds. Endocrinology: Adult and Pediatric. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2016:chap 131.

Spies JB. Current role of uterine artery embolization in the management of uterine fibroids. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2016;59(1):93-102. PMID: 26630074 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26630074.

Stewart EA. Clinical practice. Uterine fibroids. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(17):1646-1655. PMID: 25901428 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25901428.

Vilos GA, Allaire C, Laberge PY, et al. The management of uterine leiomyomas. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2015;37(2):157-181. PMID: 25767949 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25767949.

Wright JD, Ananth CV, Lewin SN, et al. Robotically assisted vs laparoscopic hysterectomy among women with benign gynecologic disease. JAMA. 2013;309(7):689-698. PMID: 23423414 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23423414.

|

Review Date:

7/20/2019 Reviewed By: John D. Jacobson, MD, Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Loma Linda University School of Medicine, Loma Linda Center for Fertility, Loma Linda, CA. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team. Editorial update on 03-24-20. |

© 1997- A.D.A.M., a business unit of Ebix, Inc. Any duplication or distribution of the information contained herein is strictly prohibited.