Hepatitis - InDepth

Highlights

The vast majority (80% to 90%) of people with hepatitis B have no symptoms whatsoever (asymptomatic) or may complain only of vague fatigue although approximately one half will recall an episode of acute hepatitis, often in the distant past. However, if undetected and untreated, a large minority of individuals (approximately 40%) will progress to chronic liver disease, liver cancer or repetitive "flares" of acute hepatitis. Accordingly, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommend testing for the hepatitis B virus (HBV) for certain groups of people who are at high risk of acquiring hepatitis B, regardless of symptoms:

- People born in regions with high rates of hepatitis B infection, such as Africa and Asia

- People who inject drugs or share needles

- Men who have sex with men

- People who are HIV-positive

- People who have sex with an infected person or who live in a household with an infected person

- All pregnant women and infants born to mothers infected with HBV

In addition, many experts recommend screening in additional populations at increased risk:

- People who have signs or symptoms of hepatitis

- People with chronic liver disease

- Those requiring immunosuppressive therapy

- People who are positive for hepatitis C

- People with multiple sexual partners

- People undergoing hemodialysis

- Household and sexual contacts of people who have hepatitis B

- Inmates at correctional institutions

Like hepatitis B, chronic hepatitis C generally does not cause any symptoms and people are often unaware they have the infection until extensive liver scarring (cirrhosis) or liver cancer has occurred, often only after many years or decades of infection. The CDC and the USPSTF recommend that all adults 18 years and older get a one-time test for the hepatitis C virus (HCV). In addition, all pregnant women should get a HCV test during every pregnancy.

The CDC also continues to recommend hepatitis C testing for people with high risk factors, including people who:

- Ever injected illegal drugs

- Received clotting factors made before 1987

- Received blood transfusion or organs donation before July, 1992

- Received chronic dialysis

- Have evidence of liver disease

- Are infected with HIV or hepatitis B

- Are born from mothers with HCV infection

However, acute infection with hepatitis C virus does not always lead to chronic infection or to liver damage. About 15% to 25% of people who are infected with hepatitis C cure their infection spontaneously without the need for medical intervention. Of those who continue to be infected, only approximately 30% will develop liver damage. The other 70% have evidence of ongoing infection but no apparent liver inflammation or scarring.

Vaccines are available to prevent hepatitis A and B. There is no vaccine for hepatitis C.

Hepatitis C treatment is rapidly transforming. In recent years, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved several new oral drug treatments, which are dramatically improving outcomes and cure rates with shorter treatment times. These drugs are taken as once-daily pills. They are very effective with very few side effects, but extremely expensive.

Introduction

Hepatitis means "inflammation of the liver." It is a disorder in which viruses, drugs or toxins in the environment produce inflammation in liver cells, resulting in their injury or destruction. If such injury persists for a long period, liver cancer can develop.

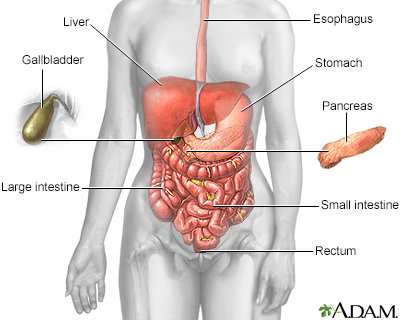

The liver is the largest internal organ in the body, occupying the upper right area of the abdomen. It performs hundreds of vital functions in digestion and metabolism. Some of the liver's key roles are:

- Process and store all of the nutrients the body requires, including sugars, fats, minerals, and vitamins.

- Manufacture essential proteins, such as albumin and blood clotting factors.

- Produce bile, the greenish fluid stored in the gallbladder that helps digest fats.

- Neutralize and eliminate potentially toxic substances, including alcohol, drugs, ammonia, and harmful by-products of digestion.

Damage to the liver can impair these and many other processes.

The esophagus, stomach, large and small intestine, which are aided by the liver, gallbladder, and pancreas, convert the nutritive components of food into energy and break down the non-nutritive components into waste to be excreted.

Hepatitis can occur from many different causes:

- Viral hepatitis is the most common kind of hepatitis. Many types of viruses can damage the liver. Hepatitis caused by the viruses A, B, and C is the focus of this report.

- Hepatitis can also result from an autoimmune condition, in which abnormally targeted immune factors attack the body's own liver cells.

- Hepatitis can also occur from medical problems, medicines, heavy or prolonged alcohol use, chemicals, and environmental toxins.

Hepatitis can be either acute (short-term) or chronic (long-term):

- Acute hepatitis lasts less than 6 months. It often causes only minimal liver damage. All hepatitis viruses can cause an acute form of liver disease. The hepatitis A virus only causes acute hepatitis; it does not cause chronic disease. Acute hepatitis caused by hepatitis C virus is usually mild with many people unaware that they have even been infected. In contrast, hepatitis B infection is more often symptomatic with fever, fatigue, jaundice and abdominal pain. Uncommonly, acute hepatitis B may cause an overwhelming infection. Acute hepatitis can also occur from non-viral causes.

- Chronic hepatitis lasts more than 6 months. It usually develops after an episode of acute hepatitis, although many people are often unaware of this acute episode, especially with hepatitis C. It may progress slowly and cause minimal liver damage, or it can progress aggressively and cause extensive damage. Chronic hepatitis can result from specific hepatitis viruses (B, C, D, and E) or some non-viral forms of hepatitis.

Although chronic hepatitis is generally considered more serious than acute hepatitis, people with either condition can have varying degrees of severity.

Causes

Most cases of hepatitis are caused by viruses that infect liver cells and begin multiplying. They are identified by the letters A through G:

- Hepatitis A, B, and C are the most common viral forms of hepatitis and are the primary focus of this report.

- Hepatitis D is a serious but less common form of hepatitis that can be chronic. It is associated with hepatitis B because the D virus relies on the B virus to replicate. Hepatitis D cannot exist without the B virus also being present.

- Hepatitis E is usually an acute form of hepatitis that, like hepatitis A, is transmitted by contact with contaminated food or water. In pregnant women, the acute form of hepatitis E can be deadly. People with weakened immune systems may develop a chronic form of hepatitis E. This virus is common in less developed global regions, but rarer in developed countries.

- Researchers are investigating additional viruses that may be implicated in hepatitis unexplained by the currently known viruses.

The name of each type of viral hepatitis condition corresponds to the virus that causes it. For example, hepatitis A is caused by hepatitis A virus (HAV), hepatitis B is caused by hepatitis B virus (HBV), and hepatitis C is caused by hepatitis C virus (HCV).

Scientists are still researching all the ways in which these viruses cause hepatitis. As the virus reproduces in the liver, the infected person produces several proteins and enzymes, including many that attach to the surface of the liver cell. Some of these may be directly responsible for liver inflammation and damage.

Autoimmune Hepatitis

Autoimmune hepatitis is an uncommon form of chronic hepatitis. Like in some other autoimmune disorders, its exact cause may be unknown. Autoimmune hepatitis may develop on its own or it may be associated with other autoimmune disorders, such as systemic lupus erythematosus. In autoimmune disorders, a misdirected immune system attacks the body's own cells and organs (in this case the liver).

Alcoholic Hepatitis

About 20% of heavy drinkers develop alcoholic hepatitis, usually between the ages of 40 to 60 years. In the body, alcohol breaks down into various chemicals, some of which are very toxic to the liver. After years of drinking, liver damage can be very severe, leading to cirrhosis. Although heavy drinking itself is the major risk factor for alcoholic hepatitis, genetic factors may play a role in increasing a person's risk for alcoholic hepatitis. Women who drink alcohol heavily are at higher risk for alcoholic hepatitis and cirrhosis than are men who drink heavily.

Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD)

NAFLD encompasses several conditions, including nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). NAFLD has features similar to alcoholic hepatitis, particularly a fatty liver, but it occurs in individuals who drink little or no alcohol. Severe obesity and diabetes are the major risk factors for NAFLD and they also increase the likelihood of complications from NAFLD. NAFLD is usually benign and very slowly progressive. In certain people, however, it can lead to cirrhosis, liver failure, or liver cancer.

Drug-Induced Hepatitis

Because the liver plays such a major role in metabolizing drugs, hundreds of medications can cause reactions that are similar to those of acute viral hepatitis. Symptoms usually appear soon after a drug is started but can appear any time. In most cases, they disappear when the drug is withdrawn, but in rare circumstances they may progress to serious liver disease. Drugs most often associated with liver interactions include:

- Halothane

- Isoniazid

- Methyldopa

- Phenytoin

- Valproic acid

- Sulfonamide drugs

Very high doses of acetaminophen (Tylenol, generic) can cause severe liver damage and even death, particularly when used with alcohol.

Toxin-Induced Hepatitis

Certain types of plant and chemical toxins can cause hepatitis. They include toxins found in poisonous mushrooms, and industrial chemicals such as vinyl chloride.

Metabolic-Disorder Associated Hepatitis

Hereditary metabolic disorders, such as hemochromatosis (accumulation of iron in the body) and Wilson's disease (accumulation of copper in the body) can cause liver inflammation and damage.

Risk Factors and Transmission

Depending on the type of hepatitis virus, there are different ways that people can acquire hepatitis. In the United States, the main ways that people contract hepatitis are:

- Hepatitis A: Through contaminated food and water.

- Hepatitis B: Through sexual contact or contaminated blood or body fluids.

- Hepatitis C: Through contact with infected blood, usually by sharing drug injection needles and syringes and in rare cases through sexual contact (particularly men who have sex with men, trans women who have sex with men, or are HIV-positive).

The hepatitis A virus is excreted in feces and transmitted by ingesting contaminated food or water. An infected person can transmit hepatitis to others if they do not follow sanitary precautions, such as thoroughly washing hands before food preparation.

People can become infected with hepatitis A by:

- Eating or drinking food or water contaminated with hepatitis A virus. Contaminated fruits, vegetables, shellfish, ice, and water are common sources of hepatitis A transmission.

- Engaging in unsafe sexual practices (oral-anal contact).

People at high risk for hepatitis A infection include:

- People who live or travel in countries where hepatitis A is common. Hepatitis A is the hepatitis strain people are most likely to encounter in developing countries.

- People living in a household with someone who has hepatitis A.

- Men (or trans women) who have sex with men.

- People who abuse drugs.

The hepatitis B virus is transmitted through blood, semen, and vaginal secretions. Situations that can cause hepatitis B transmission include:

- Sexual contact with an infected person (using a condom can help reduce but not eliminate risk).

- Sharing needles and drug injection equipment.

- Sharing personal items, (toothbrushes, razors, and nail clippers), with an infected person.

- Having direct contact with blood of an infected person, through needlestick injury or by touching open wounds.

- During childbirth, an infected mother can transmit the hepatitis B virus to her baby.

Experts recommend screening for hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection for the following high-risk groups:

- People born in regions with high rates of hepatitis B infection. These geographic regions include Africa, Asia, the Middle East, Eastern Europe, and parts of South America and the Caribbean.

- US-born people not vaccinated as infants whose parents were born in very high-risk regions (such as sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia) should also be screened for HBV.

- People who use injected drugs or who share needles.

- Men (or trans women) who have sex with men.

- People with multiple sexual partners.

- People who are HIV-positive.

- People who have sex with an infected person or who live in a household with an infected person.

- All pregnant women and infants born to mothers infected with HBV; pregnant women should be screened for HBV at their first neonatal visit.

- People who have signs or symptoms of hepatitis.

- People with chronic liver disease.

- Those requiring immunosuppressive therapy.

- People who are positive for hepatitis C.

- People undergoing hemodialysis.

- Household and sexual contacts of people who have hepatitis B.

- Inmates at correctional institutions.

The hepatitis C virus is transmitted by contact with infected human blood or semen.

- Most people are infected through sharing needles or other drug injection equipment.

- Less commonly, hepatitis C is spread through sexual contact (only rarely), sharing household items such as razors or toothbrushes, or through birth to a mother infected with hepatitis C.

The USPSTF and CDC recommend hepatitis C virus (HCV) testing for:

- All adults ages 18 years and older

- Pregnant women during each pregnancy

In addition, the CDC recommends testing people in high risk groups, including:

- Current and former drug injection users. Even if it has been many years since you injected drugs, you should get tested.

- People who are HIV-positive.

- People who have been on long-term hemodialysis.

- People who have had abnormal liver test results.

- People who received a blood transfusion, blood product, or organ before 1992 when procedures were implemented to screen blood for hepatitis C.

- People who received a blood clotting product prior to 1987, when screening procedures were implemented.

- Health care workers exposed to HCV-positive blood through needlestick injuries.

- Children born to mothers infected with hepatitis C.

Prevention

Vaccination

Hepatitis A is preventable by vaccination. Two vaccines (Havrix, Vaqta) are available, both very safe and effective. They are given in 2 shots, generally 6 months apart. A combination Hep A - Hep B vaccine (Twinrix) that contains both Havrix and Engerix-B (a hepatitis B vaccine) is also available for people age 18 years and older. It is given as 3 shots over a 6-month period.

The CDC recommends hepatitis A vaccination for:

- Children starting at age 1 year (12 to 23 months)

- Travelers to countries where hepatitis A is prevalent

- Men (or trans women) who have sex with other men

- Users of illegal drugs, especially those who inject drugs

- People with clotting factor disorders

- People with chronic liver diseases, such as hepatitis B or C

- People with close contact or planning to have close contact with an international adoptee from a high prevalence area

Prevention after Exposure to Hepatitis A

Unvaccinated people who have recently been exposed to hepatitis A may be able to prevent hepatitis A by receiving an injection with immune globulin (IG) or the hepatitis A vaccine. Either of these shots must be given within 2 weeks after exposure to be effective. The CDC recommends the vaccine for postexposure prophylaxis for healthy individuals between the ages of 1 to 40 years. Others should be given immune globulin if warranted.

Lifestyle Measures for Hepatitis A Prevention

Handwashing after using the bathroom or changing diapers can help prevent the transmission of hepatitis A. International travelers to developing countries should use bottled or boiled water for brushing teeth and drinking, and avoid ice cubes. It is best to eat only well-cooked heated food and to wash or peel raw fruits and vegetables.

Vaccination

Hepatitis B is preventable by vaccination. It may be given as a single hepatitis B vaccine, or as a combination hepatitis B and hepatitis A vaccine. The hepatitis B vaccine is usually given as a series of 3 to 4 shots (depending on the brand used) over a 6-month period.

The CDC recommends hepatitis B vaccination for:

- All children; they should receive their first dose of hepatitis B vaccine at birth and complete their vaccination series by age 6 to 18 months. Children younger than age 18 who were not vaccinated should receive "catch-up" doses.

- People who live in a household with or who have sexual relations with a person with chronic hepatitis B.

- People with multiple sex partners.

- Men (or trans women) who have sex with men.

- People who inject street drugs.

- People with diabetes.

- People with chronic liver or kidney disease.

- People who are HIV-positive.

- People whose jobs may expose them to blood or bodily fluids.

- Travelers to regions where hepatitis B is common.

Prevention after Exposure to Hepatitis B

The hepatitis B vaccine or a hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) shot may help prevent hepatitis B infection after exposure to the virus if given within 2 weeks of exposure.

Lifestyle Measures for Hepatitis B Prevention

Precautions for preventing the transmission of hepatitis B (and hepatitis C) include:

- Use a male or female condom (as appropriate); practice safe sex.

- Avoid sharing personal items such as razors or toothbrushes.

- Do not share drug needles or other drug paraphernalia (such as straws for snorting drugs).

- Clean blood spills with a solution containing 1 part household bleach to 10 parts water.

Hepatitis B (and hepatitis C) viruses cannot be spread by casual contact such as:

- Holding hands

- Sharing eating utensils or drinking glasses

- Breastfeeding

- Kissing

- Hugging

- Coughing or sneezing

There is no vaccine for hepatitis C prevention. Lifestyle precautions are similar to those for hepatitis B. In addition, people who are infected with the hepatitis C virus should avoid drinking alcohol because this can accelerate the liver damage associated with hepatitis C. People who are infected with hepatitis C should receive vaccinations for hepatitis A and B.

Prognosis

Hepatitis A is the least serious of the common hepatitis viruses. It only has an acute (short-term) form that can last from several weeks to up to 6 months. It does not have a chronic form, but approximately 10% of patients will experience one or more relapses during the 6 months after the acute illness. Most people who have hepatitis A recover completely. Once people recover, they are immune to the hepatitis A virus.

In very rare cases, hepatitis A can cause liver failure (fulminant hepatic failure) but this usually occurs in people who already have other chronic liver diseases, such as hepatitis B or C.

Hepatitis B can have an acute (limited) or chronic (long-term) form. Infants and young children are at much higher risk than adults for developing the chronic form. The vast majority (95%) of adults who are infected with hepatitis B have the acute form, recover spontaneously (without drug treatment) within a few months although the virus may persist within liver cells in their body ("latent" infection) for decades, and develop immunity to the virus. Most of these patients are unaware that they ever had hepatitis at all. People who develop immunity are not infectious and cannot pass the virus on to others. Still, blood banks will not accept donations from people who test positive for the presence of HBV antibodies.

Some patients with acute hepatitis develop a chronic form of hepatitis B. The likelihood is generally determined by their age at which the illness occurred -- this happens in 90% of neonates, 20% to 50% of those who were infected between the ages of 1 and 5 and only 5% of adults. People who have chronic hepatitis B remain infectious and are considered carriers of the disease, even if they do not have any symptoms. Some people with chronic hepatitis B may need drug treatment. Drug treatment can stop the virus from replicating and reduce the risk for cirrhosis and liver damage.

Liver disease, especially liver cancer, is the main cause of death in people with chronic hepatitis B. In fact, hepatitis B is the leading cause of liver cancer worldwide.

People with hepatitis B who are co-infected with hepatitis D may develop a more severe form of acute infection than those who have only hepatitis B. Co-infection with hepatitis B and D increases the risk of developing acute liver failure. People with chronic hepatitis B who develop chronic hepatitis D also face high risk for cirrhosis. Hepatitis D occurs only in people who are already infected with hepatitis B.

Hepatitis C has an acute and chronic form but the acute form is generally very mild and most people (75% to 85%) who are infected with the virus develop chronic hepatitis C. Chronic hepatitis C poses a risk for cirrhosis, liver cancer, or both although most patients develop neither.

The prognosis for hepatitis C depends in part on the genotype. There are six distinct genotypes of hepatitis C. In the past, some genotypes (such as genotypes 2 and 3) responded better to drug therapy than others (such as genotype 1). But that is no longer the case with the latest treatments. Researchers have made great progress in developing new and much more effective treatments for chronic hepatitis C. Over the past several years, many new drugs have been approved and other new therapies are being investigated. Hepatitis C can now usually be cured with 8-12 weeks of daily treatment with one of the newer medicines.

People with chronic hepatitis C are considered cured if they have an undetectable amount of virus in their blood 3 months after completing drug treatment. Successful treatment for hepatitis C can help reduce (but not eliminate) the risk for cirrhosis and liver cancer.

Symptoms

Symptoms of hepatitis A are usually mild, especially in children, and generally appear between 2 to 6 weeks after exposure to the virus. Adults are more likely to have fatigue, jaundice, nausea, loss of appetite, and itching that can last up to several months. Stools may appear chalky grey and urine will appear darkened.

Acute Hepatitis B

Many people with acute hepatitis B have few or no symptoms, especially individuals infected at a younger age. If symptoms appear, they tend to occur 6 weeks to 6 months after exposure and be mild and flu-like. Symptoms may include:

- Mild fever

- Nausea and vomiting

- Loss of appetite and weight loss

- Fatigue

- Muscle or joint aches

Some people develop dark urine and jaundice (yellowish skin).

Symptoms of acute hepatitis B can last from a few weeks to 6 months. Even if people infected with hepatitis B have no symptoms, they can still spread the virus.

Chronic Hepatitis B

Some people with chronic hepatitis B have symptoms similar to those of the acute form, but most people can have the chronic form for decades and show no symptoms. Liver damage may eventually be detected when blood tests for liver function are performed.

Most people with hepatitis C do not experience symptoms. Chronic hepatitis C can be present for 10 to 30 years or more, and cirrhosis or liver failure can sometimes develop before patients experience any clear symptom. Signs of liver damage may first be detected when blood tests for liver function are performed.

If initial symptoms do occur, they tend to be very mild and resemble the flu with fatigue, nausea, loss of appetite, fever, headaches, and abdominal pain. People who have symptoms usually tend to experience them about 6 weeks after exposure to the virus. Some people may not experience symptoms for up to 6 months after exposure. People who have hepatitis C can still pass the virus on to others even if they do not have symptoms.

Diagnosis

Health care providers diagnose hepatitis based on a physical examination and the results of blood tests. In addition to specific tests for hepatitis antibodies, other types of blood tests are used to evaluate liver function.

Blood tests are used to identify IgM or IgG anti-HAV antibodies, substances that the body produces to fight hepatitis A infection. IgM antibodies are present during acute hepatitis A. IgG antibodies indicate protection against infection, either due to immunization or past infection that has resolved.

There are many different blood tests for detecting the hepatitis B virus. Standard tests include:

- Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg). A positive result indicates active infection, either acute or chronic. Chronic hepatitis B is diagnosed if HBsAg persists for longer than 6 months, particularly when the HBsAb test is not positive.

- Hepatitis B surface antibody (HBsAb, also called anti-HBs). A positive result indicates an immune response to hepatitis B, either from previous infection with the virus or from having received the vaccine.

- Antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAb, also called anti-HBc). A positive result indicates either recent infection or previous infection.

- Hepatitis B envelope antigen (HBeAg) indicates that someone with a chronic infection is actively contagious.

- Antibody to HBeAg (Anti-HBeAg) may indicate recovery from chronic hepatitis, or that the chronic hepatitis B is less infectious.

- Hepatitis B DNA (HBV DNA, also called viral load) detects hepatitis B viral genetic material. It can detect an active HBV infection. It can be used for diagnosis, but is mainly used to stage the activity of the chronic infection and to monitor response to antiviral treatment in people with chronic hepatitis B.

Specific Tests for Hepatitis C

Tests to Identify the Virus

The standard first test for diagnosing hepatitis C is an enzyme immunoassay (EIA), which is used to test for hepatitis C antibodies. Antibodies can usually be detected by EIA 4 to 10 weeks after infection.

Tests to Identify Genetic Types and Viral Load

Additional tests called hepatitis C virus RNA assays may be used to confirm the diagnosis. They use a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to detect the RNA (the genetic material) of the virus. HCV RNA can be detected through blood tests as early as 2 to 3 weeks after infection. Patients who have a positive EIA but negative PCR have previously had the infection but are now cured, either spontaneously or as a result of drug therapy.

Hepatitis C RNA assays also determines virus levels (called viral load). Such levels do not reflect the severity of the condition or speed of progression, as they do for other viruses, such as HIV.

Tests for Genotype

People with hepatitis C generally need to have their hepatitis C genotype tested so that doctors can make appropriate treatment recommendations. There are 6 main genetic types of hepatitis C and more than 50 subtypes.

Specific genotypes vary in prevalence around the world. Genotype 1 was historically the most difficult to treat and is the cause of up to 75% of the cases in the U.S and Europe. The other common genetic types in the U.S. are types 2 (15%) and 3 (7%), which are more responsive to treatment than genotype 1. Genotype 4 is more common in the Middle East and Africa. Genotype 5 is limited mainly to South Africa and genotype 6 is prevalent throughout Southeast Asia. Many newer treatments for hepatitis C are highly effective across all the most common genotypes.

Liver function tests are used to detect certain substances in the blood. These may be used together with viral marker tests for any viral hepatitis:

- Bilirubin. Bilirubin is a red-yellow pigment that is normally metabolized in the liver and then excreted in the urine. In patients with hepatitis, the liver cannot process bilirubin, and blood levels of this substance rise. (High levels of bilirubin cause the yellowish skin tone known as jaundice.)

- Liver Enzymes (Aminotransferases). Enzymes known as aminotransferases, including aspartate (AST) and alanine (ALT) aminotransferases, are released when the liver is damaged. Higher amounts indicate a damaged or poorly functioning liver.

- Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP). ALP is a protein found in high amounts in the liver and bile ducts. High ALP levels can indicate bile duct blockage.

- Serum Albumin Concentration. Albumin is a protein made by the liver. A serum albumin test measures the amount of this protein in the clear liquid portion of the blood. Low levels indicate poor liver function.

- Prothrombin Time (PT). The PT test measures in seconds the time it takes for blood clots to form (the longer it takes the greater the risk for bleeding). Prothrombin is a protein produced by the liver. A prolonged PT can indicate poor liver function.

- FibroSure Test. This blood test combines the results of 6 biomarkers to generate a score that measure fibrosis (scarring) and inflammation in the liver. The test is used for people diagnosed with HCV to determine liver damage prior to treatment. It may be used in place of elastography or liver biopsy.

Ultrasonic or computed tomography (CT) scan may be used to determine the extent of cirrhosis of the liver and to check for signs of liver cancer. A newer imaging method called transient elastography measures liver stiffness and often provides a non-invasive alternative to liver biopsy for measuring fibrosis and cirrhosis.

Liver biopsy used to be considered the gold standard for confirming a diagnosis of chronic hepatitis B or C and evaluating the extent of liver damage. Nowadays, blood and imaging tests can provide much information, and liver biopsies are rarely needed. Some people may, however, need a biopsy to help assess the condition and determine treatment plans.

A biopsy involves a doctor inserting a biopsy fine needle, guided by ultrasound, to remove a small sample of liver tissue. Local anesthetic is used to numb the area. You may feel pressure and some dull pain. The procedure takes about 20 minutes to perform.

Treatment

Hepatitis A usually clears up on its own and does not require treatment. It is important to get plenty of rest and avoid drinking any alcohol or taking drugs such as acetaminophen (Tylenol) that may damage the liver until you are fully recovered.

Most adults with hepatitis B have an acute form that clears up on its own within 1 to 2 months. No medications are indicated for treating acute hepatitis B. Health care providers usually recommend that people get plenty of bed rest, drink plenty of fluids, and get adequate nutrition.

A small percentage of adults with hepatitis B develop the chronic form of hepatitis B. Infants and young children who have hepatitis B have a higher risk of developing the chronic form. There are several types of antiviral drugs used to treat chronic hepatitis B, although not all people need to take medication.

In the U.S., national medical guidelines are available to guide when people with chronic hepatitis B should receive drug therapy. Therapy is generally indicated for people with high levels of viral activity and significant liver inflammation, or those with a rapid deterioration in liver function or signs of long-term liver damage. Your provider may recommend you consult a specialist (gastroenterologist, hepatologist, or infectious disease doctor) who has experience treating hepatitis B.

People with chronic hepatitis B should receive regular monitoring to evaluate any signs of disease progression, liver damage, or liver cancer. It is also important that people with chronic hepatitis B abstain from alcohol as it may accelerate liver damage. You should check with your health care team before taking any over-the-counter or prescription medications or herbal supplements. Some medications (such as high doses of acetaminophen) and herbal products (kava) can increase the risk of liver damage. People with chronic hepatitis B should be vaccinated against hepatitis A if they are not already protected.

If the disease progresses to liver failure, liver transplantation may be an option. There is a risk of recurrence after transplantation. However, pretreatment with antiviral drugs and use of hepatitis B immune globulin after transplantation can reduce the risk for HBV recurrence.

Antiviral drug therapy is used to treat both acute and chronic forms of hepatitis C. Most people infected with hepatitis C virus develop the chronic form of the disease. Drug treatment can help prevent further liver damage and reduce the risk for liver cancer.

All people with chronic hepatitis C are potential candidates for treatment. You should discuss with your doctor your treatment options, and when treatment should begin. Treatment is especially a priority for people who have advanced fibrosis (liver scarring), cirrhosis, or high risk for complications (such as those living with HIV or those with transplanted organs).

Until recently, the standard treatment for chronic hepatitis C was dual combination therapy with the antiviral drugs pegylated interferon (peginterferon) and ribavirin. Since 2011, many new antiviral drugs have become available that have significantly improved cure rates, markedly decreased adverse reaction and transformed hepatitis C treatment. For almost all people, interferon-free drug regimens are the treatments of choice.

People with chronic hepatitis C should receive genotype testing to determine the treatment approach. There are 6 main types of hepatitis C genotypes and people have different responses to drugs depending on their genotype.

People are considered cured when they have had a "sustained virologic response" and there is no evidence of hepatitis C on lab testing. A sustained virologic response (SVR) means that the hepatitis C virus becomes undetectable during treatment and remains undetectable for at least 12 weeks after treatment has been completed. For most people who have a response, viral loads remain undetectable indefinitely. However, having hepatitis C does not protect against future new infection and some people can become re-infected or infected with a different genotype strain. Some people (less than 5%) do not respond to initial treatment and may need to be retreated with a longer or different drug regimen.

People who develop cirrhosis or liver cancer from chronic hepatitis C may be candidates for liver transplantation. Unfortunately, hepatitis C often recurs after transplantation, which can lead to cirrhosis of the new liver. Newer drugs can be very effective in helping prevent recurrence when used prior to transplantation.

People with chronic hepatitis C should abstain from alcohol because it can speed cirrhosis and end-stage liver disease. They should also check with their providers before taking any non-prescription or prescription medications, or herbal supplements. It is also important that people who are infected with HCV be tested for HIV, as the combination of HIV and HCV produces a more rapid progression of liver disease than HCV alone. They should also be tested for Hepatitis B since the drugs used to treat hepatitis C may cause "latent" hepatitis B to re-emerge.

Popular herbal remedies for hepatitis include ginseng, glycyrrhizin (a compound in licorice), catechin (found in green tea), and silymarin (found in milk thistle). However, there is no evidence that these herbs are helpful for hepatitis or other liver diseases.

People with hepatitis should be aware that some herbal remedies and dietary supplements can cause liver damage. In particular, kava (an herb promoted to relieve anxiety and tension) is dangerous for people with chronic liver disease. Other herbs associated with liver damage include:

- Chaparral

- Kombucha mushroom

- Mistletoe

- Pennyroyal

- Some traditional Chinese herbs

Liver transplantation may be an option for people with severe cirrhosis or for people with liver cancer that has not spread beyond the liver.

Recurrence of hepatitis after transplantation is a concern. Treatment with antiviral drugs before transplantation is recommended to help reduce the risk for recurrence.

Current 5-year survival rates after liver transplantation are about 80%, depending on different factors. People report improved quality of life and mental functioning after liver transplantation.

In researching transplant centers, ask how many transplants they perform each year and their survival rates. Compare those numbers to those of other transplant centers.

Medications

Seven drugs are currently approved in the United States for treatment of chronic hepatitis B:

- Peginterferon alfa-2a (Pegasys)

- Interferon-alfa-2b (Intron A)

- Entecavir (Baraclude)

- Lamivudine (Epivir-HBV)

- Telbivudine (Tyzeka)

- Tenofovir (Viread)

- Adefovir (Hepsera)

These drugs do not cure hepatitis B but they can block the replication of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and lower the amount of HBV in the body. They may also help prevent the development of progressive liver disease (cirrhosis and liver failure) and the development of liver cancer.

Entecavir and tenofovir are currently the preferred drugs for first-line, long-term treatment. They have shown better results and less likelihood for drug resistance than the other approved medications.

Peginterferon alfa-2a

Peginterferon alfa-2a (Pegasys) is also called pegylated interferon. It is given as a weekly injection. Interferon alfa-2b is an older injectable interferon drug that used to be the standard treatment for hepatitis B but is no longer commonly used.

Common side effects include flu-like symptoms, such as fever, chills, muscle aches, joint pains, and headaches. The drug can also cause depression, anxiety, irritability, and insomnia and should be used with caution in people with a history of mental illness. Peginterferon alfa-2a can also increase the risk for infections, heart problems, stroke, and autoimmune disorders, as well as other serious conditions.

Entecavir

Entecavir (Baraclude) is an oral drug that is taken once daily. Entecavir is a nucleoside analog drug. Lamivudine (Epivir-HBV) and telvibudine (Tyzeka) are also nucleoside analogs, but they tend to have higher rates of drug resistance than entecavir. For this reason, entecavir is the preferred nucleoside analog drug for treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Common side effects of entecavir and other nucleoside analogs are uncommon but include headache, fatigue, dizziness, and nausea.

Tenofovir

Tenofovir (Viread; Vemlidy) is an oral drug that is taken once daily. It belongs to a class of antiviral drugs called nucleotide analogs. Adefovir (Hepsera) is an older drug of this class but it is not used as commonly as tenofovir. Common side effects of these drugs include weakness, headache, stomach pain, and itching.

Serious Side Effects of Entecavir and Tenofovir

People who take entecavir or tenofovir (or a similar antiviral drug) should be aware that:

- Stopping the drug can increase the risk for severe and sudden worsening symptoms of hepatitis B. People who discontinue drug therapy should be closely monitored for several months after stopping treatment. In some cases, drug treatment may need to be reinstated.

- Lactic acidosis (buildup of acid in the blood) is a rare but serious complication of these drugs. Signs and symptoms of lactic acidosis include feeling extremely tired, unusual muscle pain, difficulty breathing, stomach pain with nausea and vomiting, feeling cold (especially in the arms and legs), feeling dizzy or light-headed, or a fast or irregular heartbeat. Immediately contact your health care provider if you experience these symptoms.

- Hepatotoxicity (liver damage) is another serious complication. Signs and symptoms include yellowing of skin or white part of eyes (jaundice), dark urine, light-colored stool, or lower stomach pain. Immediately contact your provider if you experience these symptoms.

- Kidney damage (nephrotoxicity) may occur, particularly in people who already have kidney problems.

- Tenofovir may cause osteoporosis (thinning and weakening of bones) when given over many years.

Tenofovir is available in two different forms, tenofovir disoproxil and a targeted prodrug called tenofovor alafenamide (TAF). Both forms are FDA approved for treatment of chronic hepatitis B.

Pegylated interferon alfa (Pegasys or Peg-Intron) combined with the nucleoside analog drug ribavirin (Copegus) used to be the gold standard treatment for chronic hepatitis C. In recent years, new antiviral drugs have dramatically changed hepatitis C treatment regimens and improved outcomes:

Treatment by Genotype

Genotype 1 is the most common type of hepatitis C in North America and Western Europe and used to be more difficult to treat than genotypes 2 and 3. Examples of available drugs include sofosbuvir-velpatasvir, simeprevir plus sofosbuvir, elbasvir-grazoprevir with or without ribavirin, ombitasvir-paritaprevir-ritonavir plus dasabuvir with or without ribavirin, daclatasvir-sofosbuvir, and glecaprevir-pibrentasvir.

For genotype 2 or 3, examples of treatment regimens include sofosbuvir-velpatasvir, sofosbuvir-daclatasvir or sofosbuvir-ribavirin for 12 weeks. For genotype 3, these combinations should be continued for 24 rather than 12 weeks. For genotype 1 or 4, ledipasvir-sofosbuvir for 12 to 24 weeks.

FDA has recently approved glecaprevir-pibrentasvir for all 6 genotypes in adult and pediatric patients. It is administered for 8 to 12 weeks.

Currently, hepatitis C therapy is a rapidly evolving field. New drugs and drug combinations are being approved very quickly and treatment guidelines are constantly updated to reflect these advances. The current American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases can be accessed at: www.hcvguidelines.org.

Side Effects

Pegylated interferon alfa is given as an injection once a week. Ribavirin is taken as a pill twice a day. Common side effects of peginterferon-ribavirin treatment include fatigue, stomach upset, and flu-like symptoms. More serious side effects may include:

- Depression, anxiety, insomnia, and other mental health problems (caused by peginterferon)

- Decrease in white blood cell count (caused by peginterferon) and decrease in red blood cell count (caused by ribavirin)

- Skin rash, cough, shortness of breath (caused by ribavirin)

- Risk for birth defects (associated with ribavirin)

Side effects of sofosbuvir (Sovaldi), simeprevir (Olysio), and ledipasvir-sofosbuvir (Harvoni) are uncommon but include fatigue, headache, nausea, diarrhea, and insomnia. Rash, including serious sensitivity to light (photosensitivity), is a common side effect of simeprevir.

The vast majority of newer agents have no known or rare side effects.

Resources

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention -- www.cdc.gov/hepatitis

- American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases -- www.aasld.org

- American Liver Foundation -- liverfoundation.org

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases -- www.niddk.nih.gov

- HCV Guidance: Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C -- www.hcvguidelines.org

- Hepatitis B Foundation -- www.hepb.org

- United Network for Organ Sharing -- unos.org

References

AASLD-IDSA HCV Guidance Panel. Hepatitis C Guidance 2018 Update: AASLD-IDSA recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67(10):1477-1492. PMID: 30215672 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30215672.

Brahmania M, Feld J, Arif A, Janssen HL. New therapeutic agents for chronic hepatitis B. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(2):e10-e21. PMID: 26795693 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26795693.

Brown RS Jr, McMahon BJ, Lok AS, et al. Antiviral therapy in chronic hepatitis B viral infection during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2016;63(1):319-333. PMID: 26565396 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26565396.

Dienstag JL. Viral hepatitis. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 117.

Indolfi G, Easterbrook P, Dusheiko G, et al. Hepatitis B virus infection in children and adolescents. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4(6):466-476. PMID: 30982722 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30982722.

Indolfi G, Easterbrook P, Dusheiko G, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection in children and adolescents. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4(6):477-487. PMID: 30982721 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30982721.

Jonas MM, Lok AS, McMahon BJ, et al. Antiviral therapy in management of chronic hepatitis B viral infection in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2016;63(1):307-318. PMID: 26566163 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26566163.

LeFevre ML; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for hepatitis B virus infection in nonpregnant adolescents and adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(1):58-66. PMID: 24863637 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24863637.

Lok AS, McMahon BJ, Brown RS Jr, et al. Antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis B viral infection in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2016;63(1):284-306. PMID: 26566246 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26566246.

Ly KN, Xing J, Klevens RM, Jiles RB, Ward JW, Holmberg SD. The increasing burden of mortality from viral hepatitis in the United States between 1999 and 2007. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(4):271-278. PMID: 22351712 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22351712.

Martin P, DiMartini A, Feng S, Brown R Jr, Fallon M. Evaluation for liver transplantation in adults: 2013 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the American Society of Transplantation. Hepatology. 2014;59(3):1144-1165. PMID: 24716201 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24716201.

Naggie S, Wyles DL. Hepatitis C. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 154.

Seto WK, Lo YR, Pawlotsky JM, Yuen MF. Chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet. 2018;392(10161):2313-2324. PMID: 30496122 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30496122.

Sjogren MH, Bassett JT. Hepatitis A. In: Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ, eds. Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease: Pathophysiology/Diagnosis/Management. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2016:chap 78.

Sundaram V, Kowdley K. Management of chronic hepatitis B infection. BMJ. 2015;351:h4263. PMID: 26491030 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26491030.

Terrault NA, Lok ASF, McMahon BJ, et al. Update on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidance. Hepatology. 2018;67(4):1560-1599. PMID: 29405329 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29405329.

Thio CL, Hawkins C. Hepatitis B virus. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 145.

Thio CL, Hawkins C. Hepatitis delta virus. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 146.

US Preventive Services Task Force, Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, et al. Screening for Hepatitis C Virus Infection in Adolescents and Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2020 Mar 2. PMID: 32119076 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32119076.

Webster DP, Klenerman P, Dusheiko GM. Hepatitis C. Lancet. 2015;385(9973):1124-1135. PMID: 25687730 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25687730.

Wedemeyer H. Hepatitis C. In: Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ, eds. Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease: Pathophysiology/Diagnosis/Management. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2016:chap 80.

Wells JT, Perrillo R. Hepatitis B. In: Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ, eds. Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease: Pathophysiology/Diagnosis/Management. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2016:chap 79.

Reviewed By: Barry S. Zingman, MD, Medical Director, AIDS Center, and Clinical Director, Infectious Diseases, Montefiore Medical Center; Professor of Medicine, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team. Editorial update on 05/01/20.