Colon and rectal cancers - InDepth

Highlights

A number of major organizations, including The American Cancer Society (ACS), The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), the American College of Physicians, and The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG), have developed guidelines related to screening for colorectal cancer. While there are some differences among these guidelines, they generally recommend that adults ages 45 to 75 who are at average risk for colorectal cancer should be screened with one of these methods:

- Colonoscopy every 10 years.

- Flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 to 10 years.

- Double-contrast barium enema (DCBE) every 5 years.

- CT colonography (CTC), also called virtual colonoscopy, every 5 years.

- Stool test options for screening, including: Guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (gFOBT) every year, fecal immunochemical test (FIT) every year, stool DNA test (sDNA) every 3 years.

Cologuard is a stool DNA screening test for colorectal cancer. The home-based test uses a stool sample to check for the presence of blood and DNA changes that may indicate cancer.

Introduction

Cancers of the colon and rectum, often collectively referred to as colorectal cancer, are tumors that develop in the large intestine.

More than 90% of colorectal tumors develop from a type of polyp called adenomatous polyps. There are many types of polyps. They are common, mostly non-cancerous (benign) tumors. Adenomatous polyps, also called adenomas, are a specific type of polyp that has a greater likelihood of changing into cancer. Because of this risk, adenomas are considered precancerous.

Adenomas are gland-like growths that develop on the lining of the large intestine. They are usually either:

- Tubular polyps, which protrude in a mushroom-like fashion, or

- Villous adenomas, which are flat and spreading and are more likely to become malignant (cancerous)

When adenomas become malignant (cancerous), they are referred to as adenocarcinomas. Adenocarcinomas are cancers that originate in glandular tissue cells. Adenocarcinoma is the most common type of colorectal cancer.

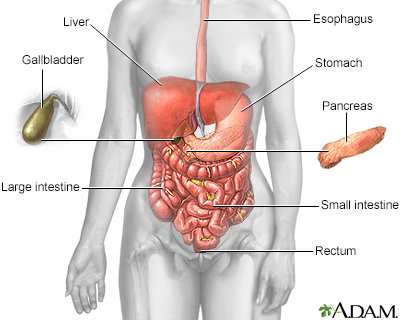

Digestion takes place in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, which is basically a long tube that extends from the mouth to the anus. It is a complex organ system that first carries food from the mouth down the esophagus to the stomach. Food then travels through the small and large intestines before being excreted through the rectum and out the anus.

The esophagus, stomach, and large and small intestine, aided by the liver, gallbladder, and pancreas, convert the nutritive components of food into energy and break down the non-nutritive components into waste to be excreted.

The esophagus is a narrow muscular tube, about 9 1/2 inches long, that begins below the tongue and ends at the stomach.

In the stomach, acids and stomach motion break food down into particles small enough so that the small intestine can absorb nutrients.

The small intestine, despite its name, is the longest part of the gastrointestinal tract. It extends from the stomach to the large intestine and is about 20 feet long. Food passes from the stomach through the small intestine's three parts: first the duodenum, then the jejunum, and finally the ileum. Most of the digestive process occurs in the small intestine.

Undigested material, such as plant fiber, is passed next to the large intestine, or colon, mostly in liquid form. The colon is wider than the small intestine but only about 6 feet long. The colon absorbs excess water into the blood. The remaining waste matter is converted to feces through bacterial action. The colon is a continuous structure but it is characterized as having several components.

Cecum and Appendix

The cecum is the first part of the colon after the small intestine. The appendix is attached to the cecum. These structures are located in the lower-right part of the abdomen. The colon continues onward in several sections:

- The first section, the ascending colon, extends upward from the cecum on the right side of the abdomen.

- The second section, the transverse colon, crosses the upper abdomen to the left side.

- The third section extends downward on the left side of the abdomen toward the pelvis and is called the descending colon.

- The final section is the sigmoid colon.

Rectum and Anus

Feces are stored in the descending and sigmoid colon until they are passed through the rectum and anus. The rectum extends through the pelvis from the end of the sigmoid colon to the anus.

Causes

In most cases of colon or rectal cancers, the cause or causes are unknown. Defects in genes that normally protect against cancer play the major role in causing polyp cells to change and become cancerous.

Sometimes these cancerous changes are caused by inherited genetic defects and are associated with family histories of colorectal cancer. However, most of the genetic mutations involved in colon cancers appear to arise spontaneously rather than being inherited. In such cases, environmental or other factors may trigger genetic changes in the intestine that lead to cancer.

Risk Factors and Prevention

The American Cancer Society estimates that 101, 420 new cases of colon cancer and 44,180 new cases of rectal cancer will be diagnosed in the United States in 2019.

Rates of colorectal cancer have been decreasing in the United States. This may be due to more people getting regular screenings for colorectal cancer, and fewer people engaging in risk factors, such as smoking. However, many people age 50 years and older still do not receive their recommended screenings.

Colorectal cancer risk increases with age. More than 90% of these cancers occur in people over age 50 years.

Men have a slightly higher risk than women for developing colorectal cancer.

African-Americans have the highest risk of being diagnosed with, and dying from, colorectal cancer. Among Caucasians, Jews of Eastern European (Ashkenazi) descent have a higher rate of colorectal cancer. Asian Americans/Pacific Islanders, Hispanics/Latinos, and American Indians/Alaska Natives have a lower risk than Caucasians.

About 20% to 25% of colorectal cancers occur among people with a family history of the disease. People who have more than one first-degree relative (sibling or parent) with the disease are especially at high risk. The risk is even higher if the relative was diagnosed with colorectal cancer before the age of 60.

A small percentage of people with colorectal cancer have an inherited genetic abnormality that is associated with an increased risk for the disease. The most commonly associated inherited colorectal cancer syndromes associated with genetic mutations include familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC).

- Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP). FAP is caused by mutations in a gene called the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene, which normally helps suppress tumor growth. In its defective form, it accelerates cell growth leading to polyps. The APC mutation can be inherited from either parent. People with FAP develop hundreds to thousands of polyps in the colon. If FAP is left untreated, virtually everyone who inherits this condition develops cancer by age 45. Polyps usually first appear when people are in their mid-teens. FAP also increases the risks for other types of cancers including stomach, thyroid, pancreatic, liver, and small intestine cancers.

- Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colorectal Cancer (HNPCC). HNPCC is also known as Lynch syndrome. Most people with Lynch syndrome develop colon cancer by age 45. HNPCC is caused by a mutation in one of several different genes. People with HNPCC are prone to other cancers, including uterine and ovarian cancers, as well as cancers of the small intestine, liver, urinary tract, and central nervous system.

Colon cancer is more common in developed nations than less developed countries. "Western" lifestyle factors are most likely the reason. Diets high in red and processed meats, lack of physical activity, excess weight, and smoking are all associated with an increased risk for colorectal cancer.

Dietary Factors

A diet high in red and processed meats increases the risk for colorectal cancer. Diets high in fruits and vegetables may help reduce risk. The evidence is mixed on whether high intake of dietary fiber is protective. It is also not clear whether there is an association between colorectal cancer risk and deficiencies of folic acid. In any case, neither folic acid nor fiber supplements appear to lower the risk for colorectal cancer. The best sources for dietary fiber and vitamins are fruits, vegetables, nuts, and whole grains.

Alcohol and Smoking

Excessive alcohol use and long-term smoking increase the risk for colorectal cancer.

Obesity

Obesity is associated with an increased risk for colorectal cancer, especially for men.

Physical Inactivity

A sedentary lifestyle increases the risk of developing colorectal cancer. Regular exercise may help reduce risk.

Adenomatous Polyps (Adenomas)

People who have had adenomas have an increased risk of developing colorectal cancer. When these polyps are detected during a colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy they can be removed before they turn cancerous.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

IBDs include Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis. The long-term inflammation caused by these chronic disorders can increase the risk for colorectal cancer. IBD is different from irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), which does not increase colorectal cancer risk.

Diabetes

Many studies have identified an association between type 2 diabetes and colon cancer. Both diseases share the common risk factors of obesity and physical inactivity, but diabetes itself is a risk factor for colorectal cancer.

Colorectal cancer screenings are a very important preventive measure. Healthy lifestyle measures are also important. For people with certain types of colorectal cancer risk factors, preventive medications may be helpful.

Lifestyle Changes and Prevention

The best way to prevent colorectal cancer is to engage in a healthy lifestyle, which include:

- Exercising regularly

- Eating a healthy diet low in meat and high in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains

- Not smoking

- Not drinking alcohol in excess

- Avoiding obesity

Medications and Prevention

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are commonly used pain relievers that include aspirin, ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin, generic), naproxen (Aleve, generic), and the COX-2 inhibitor celecoxib (Celebrex).

- Studies suggest that daily low-dose aspirin may help prevent colorectal cancer in people who are at high-risk for genetic forms of the disease, such as Lynch syndrome.

- There is some evidence that aspirin therapy may help improve the odds of survival after a diagnosis of colorectal cancer (secondary prevention). Studies are ongoing.

- However, long-term use of aspirin and other NSAIDs carries serious risks for stomach bleeding. The American Cancer Society (ACS) and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) do not recommend the routine use of aspirin, other NSAIDs, or other types of medications to prevent colorectal cancer in people at average risk for this disease.

Symptoms

It is common to have colon or rectal cancer without symptoms. Many people are free of symptoms until their tumors are quite advanced.

Symptoms associated with colorectal cancer may also be caused by other conditions. These symptoms include:

- Changes in bowel movements, such as diarrhea or constipation, or change in consistency or size of stools

- Feeling that the bowel has not emptied completely after a bowel movement

- Abdominal discomfort, such as gas, bloating, and cramps

- Rectal bleeding or blood in stool

- Pain when having a bowel movement

- Unexplained weight loss

- Unexplained iron-deficiency anemia (low red blood cell count)

- Weakness and fatigue

Diagnosis and Screening

Colon and rectal cancers can be detected early using the screening tests discussed below. These tests can find precancerous polyps and colorectal cancers at stages early enough for complete removal and cure.

The American Cancer Society (ACS), the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), the American College of Physicians, and the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) all have made similar, although not identical, recommendations concerning screening for colorectal cancer.

Discuss with your health care provider whether you are at average- or high-risk for colorectal cancer, and which screening test and schedule is most appropriate for you. (See descriptions of screening tests below for more information about the individual tests.)

Screening for Adults with Average Risk for Colorectal Cancer

General age recommendations for colorectal cancer screening are:

- Screening should begin at age 45 years and continue until age 75.

- Screening is not routinely recommended for adults age 75 and older. However, the decision to screen needs to be made on an individual basis.

Several options and schedules for screening are recommended. The choices include:

- Colonoscopy every 10 years

- Flexible sigmoidoscopy either every 5 years or every 10 years when accompanied by stool testing with FIT done every year

- Double-contrast barium enema (DCBE) every 5 years

- CT colonography (CTC), also called virtual colonoscopy, every 5 years

Stool tests are another approved way to screen for colon cancer. Several options are available:

- Guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (gFOBT) every year

- Fecal immunochemical test (FIT) every year

- Stool DNA test (sDNA) every 3 years

If a stool test shows an abnormal result, a colonoscopy is required

Screening for Adults at High-Risk for Colorectal Cancer

People at high risk for colorectal cancer should undergo colonoscopy for screening. The most important risk factors that may prompt screening before age 50 or frequent screenings are:

- A known family history of inherited colorectal cancer syndromes such as familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) or hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC).

- A strong family history of colorectal cancer or polyps, especially in first-degree relatives (parent, sibling, or child) who developed these conditions younger than the age of 60.

- A personal history of colorectal cancer or adenomatous polyps (Adenomas).

- A personal history of chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), such as Crohn disease or ulcerative colitis.

People in these high-risk groups who have changes that are identified as precancerous during colonoscopy will likely have their doctors discuss with them the possibility of a preventive (prophylactic) colectomy (removal of the entire colon).

Colonoscopy

Colonoscopy allows a doctor to view the entire length of the large intestine using a colonoscope, which is inserted into the rectum and snaked through the intestine. A colonoscope is a long, flexible tube that has a video camera at one end. The doctor views images from the colonoscope on a video display monitor.

The test takes about 30 minutes to perform. If polyps are found, the doctor will remove them. The person is given a sedative prior to the test, which produces a comfortable "twilight" sleep.

In order for the doctor to perform a successful colonoscopy, the colon and rectum must be completely empty. Your doctor will give you instructions for how to prepare during the days preceding the tests, and specific foods and liquids to avoid eating and drinking. The day before the test you will be given a laxative solution to clean out the colon. Many people find this cleansing more unpleasant than the colonoscopy itself.

Colonoscopy is generally a safe procedure. In very rare cases, complications, such as bowel perforation, can occur.

Flexible Sigmoidoscopy

Sigmoidoscopy is similar to colonoscopy but only examines the rectum and the lower 2 feet of the colon. (In contrast, colonoscopy allows the doctor to view the entire colon.) The procedure takes about 10 to 20 minutes, and sedation is optional. Preparation procedures are less demanding than those for colonoscopy.

Double-Contrast Barium Enema (DCBE)

The DCBE test uses an x-ray to image the entire large intestine. The test takes about 30 to 45 minutes, and sedation is not required. Preparations are similar to those for colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy. For the test, barium sulfate is inserted into the rectum using a small, flexible tube. The colon is then pumped with air to help the barium spread through the colon. If polyps are detected in the x-ray, your doctor may recommend you have a colonoscopy for further investigation and polyp removal.

Virtual Colonoscopy

Virtual colonoscopy, also called CT colonoscopy, uses x-rays delivered by computed tomography (CT) scan to take three-dimensional images of the colon. The test takes only 10 minutes to perform, and does not require sedation. (It does require the same preparations as standard colonoscopy to clean out the colon and bowel.) Air is pumped into the rectum through a small flexible tube. The person is then slid into a CT scanner, which takes rapid images. If polyps are detected, a standard colonoscopy is required.

Fecal Occult Blood Test (FOBT)

A FOBT is a take-home test that uses stool samples to detect hidden (occult) blood in feces. It may detect small amounts of blood in stool from polyps or a tumor, even when stools appear normal. Your doctor will give you a kit with instructions on how to take stool samples and prepare them. Your doctor will also inform you about what medications and foods need to be avoided in the days prior to the test. The test kit and samples are sent to a laboratory and results usually come back in a short time. If blood is found in the stool samples, you will need to have a colonoscopy.

Fecal Immunochemical Test (FIT)

The FIT is a take-home test for hidden (occult) blood. The test is similar to the FOBT, but people do not need to follow medication or dietary restrictions. As with the FOBT, a colonoscopy is recommended if blood is found in the stool.

Stool DNA Test (sDNA)

Like the FIT and the FOBT, the sDNA test is done at home and uses fecal samples. No dietary restrictions or test prep are required. Unlike FIT and FOBT, which require multiple stool samples, the sDNA test uses only one bowel movement. In addition to testing for the presence of blood, this test looks for abnormalities in genetic material associated with cancer or precancerous polyps. If DNA mutations are found, a colonoscopy is needed. The first sDNA test was approved by the FDA in 2014. Medicare will cover the test but some insurance carriers may not pay for the full cost.

A doctor makes a diagnosis of colorectal cancer based on results of several types of tests. These tests include:

Biopsy

During a colonoscopy, the doctor can remove a tissue sample, which is sent to a laboratory for testing. A biopsy is the only way to definitively diagnose colorectal cancer.

The tumor may also be tested for biomarkers such as microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) and mismatch-repair deficient (dMMR). Biomarker testing can help guide the optimal treatment regimen.

Blood Tests

Routine blood testing after a diagnosis of colon cancer is made includes a CBC (complete blood count), LFTs (liver function tests) and a CEA (carcinoembryonic antigen) level.

These tests may help your doctor monitor for recurrences of colon cancer after treatment. By themselves, they cannot diagnose cancer and are not used as screening tests.

Imaging Tests

Various types of imaging tests can help detect the presence of cancer or find out how far the cancer has spread. These tests include:

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan

- Computed tomography (CT) scan

Treatment

A diagnosis of cancer will lead to staging and other tests to help determine the outlook and the appropriate treatments. Treatment for colorectal cancer can include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation or a combination of these methods.

- Surgery is used for early-stage colorectal cancer. Usually, the tumor is removed along with part of the colon and nearby lymph nodes.

- Chemotherapy may be given after surgery to reduce the risk of the cancer recurring. It may also be given along with radiation before surgery to reduce tumor size.

- Radiation therapy is not usually used in early-stage colon cancer, but is commonly used to treat early-stage rectal cancer. It is often combined with chemotherapy (chemoradiation).

- Targeted therapy with a biologic drug, usually in combination with chemotherapy, may be used for people with advanced (metastatic) cancer.

- Clinical trials may be available for all stages of colorectal cancer.

There are several methods for staging colorectal cancer. An older system, known as Dukes', categorizes four basic stages: A, B, C, and D. The current TMN system characterizes the primary tumor (T stage), the lymph node status (N stage), and whether or not the cancer has spread or metastasized (M stage). The results of TMN are combined to determine the stage of the cancer (typically, stage I, II, III, or IV). The stage correlates with the type of treatment recommended as well as the overall prognosis.

Colorectal cancer stages and treatment options are:

Stage 0 (Carcinoma in situ)

- In stage 0, cancer cells are fully contained in the innermost lining (mucosa) of the colon or rectum, and have not yet invaded the wall of the colon.

- Treatment for stage 0 colon cancer usually involves surgical removal of the polyp (polypectomy) during colonoscopy. For larger lesions, colon resection may be needed.

- Treatment for stage 0 rectal cancer usually involves surgical removal of the polyp (polypectomy) during colonoscopy. For larger lesions, full rectal resection may be needed.

Stage I

- In stage I, the cancer has spread through the mucosa of the colon wall into middle layers of tissue.

- Treatment for stage I colon cancer involves resection (surgical removal) of the tumor. The tumor may be removed along with part of the colon (colectomy).

- Treatment for stage I rectal cancer may involve only local resection (surgical removal) or a wider resection.

Stage II

- In stage IIA, the cancer has spread beyond the middle layers to the outer tissues of the colon or rectum wall. In stage IIB, the cancer has penetrated through the colon or rectum wall into nearby tissue or organs.

- Treatment for stage II colon cancer involves resection of a wider area of the colon and the ends are re-attached (anastamosed). The decision to use adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with stage II colon cancer is complicated and most often not used outside of a clinical trial.

- Treatment for stage II rectal cancer involves resection of a wider area. Radiation therapy, most often before surgery, may be used for larger tumors. Chemotherapy after surgery (adjuvant chemotherapy) is considered standard treatment for stage II rectal cancer.

Stage III

- In stage III, lymph nodes are involved but not distant sites. Stage III is divided into stages IIIA, IIIB, and IIIC depending on different combinations of T stages and N stages.

- Treatment for stage III colon cancer involves surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy. A wide area of the colon is removed, and the ends are re-attached (anastamosed).

- For people with stage III rectal cancer, treatment includes chemotherapy and radiation, either before or following surgery.

Stage IV

- Stage IV is cancer that has metastasized or spreads to organs beyond the colon and nearby lymph nodes, such as the liver or lungs.

- Treatment for stage IV cancer may include surgery to remove or bypass obstructions in the intestine. In these circumstances, surgery is considered palliative in that it may improve symptoms but will not lead to a cure. In some cases, surgery may also be performed to remove tumors in areas that the cancer has spread, such as the liver, ovaries, or lung.

- Chemotherapy is standard treatment for metastasized cancer. In advanced colorectal cancer, chemotherapy is either given directly into the arteries of the liver or intravenously (through a vein). Currently, there are 13 active U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drugs for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Most use fluorouracil (5-FU) in combination with other cancer-fighting drugs, such as oxaliplatin or irinotecan.

- Targeted therapy with newer biologic drugs may be an option for some people. It is often used in combination with conventional chemotherapy.

- For rectal cancer, radiation therapy may be used in place of chemotherapy or in combination with it. Radiation is often used as palliative treatment to help ease symptoms and reduce pain.

Colorectal cancer is among the most curable of cancers when it is caught in its early stages. The term "5-year survival" means that people have lived at least 5 years since diagnosis. The 5-year survival rate for colon cancer diagnosed and treated at stage I is 90%. The rates fall to 70% for stage II and stage III, and 12% for stage IV. However, there are other factors besides stage that can affect a person's prognosis.

After cancer treatment concludes, follow-up care is important to detect any signs of cancer recurrence. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has follow-up care guidelines for people treated for stage II or stage III colorectal cancer. Stage I cancer is less likely to recur. The guidelines recommend:

- Timing. Follow-up care is recommended for the 5 years following treatment. 80% of colorectal cancer recurrences are discovered 2 to 3 years after surgery, and 95% of recurrences are found within 5 years. In addition to checking for signs of cancer, follow-up care can help monitor for any long-term side effects from treatment. Discuss with your health care provider what type of follow-up care you may need after 5 years.

- Physical Examination. You should see your provider for a physical examination every 3 to 6 months for the first 5 years after treatment is completed.

- CEA Blood Test. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels should be measured every 3 to 6 months for 5 years. CEA is a protein that is found in the blood and is associated with cancer. High CEA levels in the blood may indicate that the cancer has recurred or has spread to other parts of the body.

- Imaging Tests. A computerized tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis should be performed every year for the first 3 to 5 years after treatment. (People at higher risk for recurrence should get a CT scan every 6 to 12 months during this time.) For rectal cancer, a pelvic CT scan is recommended every 6 to 12 months for the first 3 years, and then every year for the 4th and 5th year.

- Colonoscopy. You will need a colonoscopy 1 year after surgery, and if normal, repeated 3 years later. After that, most people will have a colonoscopy once every 5 years. However, if your colonoscopy reveals polyps or other abnormal findings, you may need more frequent screenings.

Healthy Lifestyle

Be sure to follow measures to promote good health. This includes:

- Maintaining a healthy weight

- Not smoking

- Eating a healthy diet

- Engaging in regular physical activity

Surgery

In the earliest stages of colorectal cancer (stage 0 and some stage I cases) polyps can be removed during a colonoscopy in a procedure called a polypectomy. Early-stage superficial cancers that are not deep can also be removed through excision during colonoscopy. Unlike colectomy, these procedures do not involve cutting through the abdominal wall.

Surgical removal of the tumor (resection) is the standard initial treatment for potentially curable colorectal cancers (cancers that have not spread beyond the colon or lymph nodes).

Unless colon cancer is very advanced, most tumors are removed by an operation known as colectomy:

- Colectomy involves removing the cancerous part of the colon and nearby lymph nodes.

- The surgeon then reconnects the intestine in a procedure called anastomosis.

- If the surgeon cannot reconnect the intestine, usually because of infection or obstruction, the surgeon will perform a colostomy. (which may be temporary).

- Stents, expandable metal tube-like devices, may be used as preparation before surgery to manage blockage and to keep the intestine open.

The Surgical Approach

The standard technique for a colectomy is open, invasive surgery. Laparoscopy, sometimes called "keyhole surgery," is a newer, and less invasive, method:

- Open surgery uses a wide incision to open the person's abdomen. The surgeon then performs the procedures with standard surgical instruments. This is the usual method for performing colectomy.

- Laparoscopy uses a few small incisions through which the surgeon passes a fiber-optic tube (laparoscope) containing a small camera.

Recuperation and Side Effects

After a colectomy, you will need to stay in the hospital until you regain normal bowel function and can eat and drink normally. The hospital stay is usually about 4 to 7 days. You will first be on a liquid diet followed by soft, low-fiber foods and eventually normal foods. There are usually no dietary restrictions after recovery.

Any abdominal surgery may be associated with post operative fatigue and weakness. Daily short walks with increasing distances are encouraged. It may take 4 to 6 weeks for full recovery.

A colostomy or ileostomy is performed to bypass the colon and rectum. Colostomy is a surgical procedure that brings one end of the large intestine out through the abdominal wall. (An ileostomy brings the small intestines to the abdominal wall.) The surgeon creates a passage, called a stoma, through the abdominal wall that is connected to the colon.

Feces and gas moving through the intestine pass through the stoma and drain into a special colostomy bag (ostomy pouch) that is attached to the stoma. The bag needs to be emptied several times a day. You will be taught how to keep the area around the stoma clean so as to avoid infection.

The colostomy may be temporary and reversed by a second operation after about 3 to 6 months. If the rectum and sphincter muscles in the rectum need to be removed, the colostomy is typically permanent. The need for colostomies (especially permanent ones) is higher after surgery for rectal cancer than for colon cancer.

Surgical treatments for cancer in the rectum are complex since they involve muscles and tissue that are critical for urinary, bowel, and sexual function.

As with colon cancer, early-stage tumors may be removed through local excision or polypectomy. Surgery for more advanced cancers involves cutting away the diseased part of the rectum (rectal resection, also known as proctectomy.)

After rectal resection, the surgeon will perform either an:

- Anastomosis. The surgeon reconnects the healthy parts of the rectum, or reattaches the remaining part of the rectum to the colon. This is called sphincter-preserving surgery.

- Colostomy. If the tumor location prevents the surgeon from performing an anastomosis, then a colostomy will be performed. The colostomy may be temporary, but if the entire rectum is removed then the colostomy is permanent.

Depending on the extent and location of the cancer, other surgical procedures may be performed. In rare cases, if the cancer has spread beyond the rectum to nearby organs, a pelvic exenteration may be required. This involves removal of the rectum, anus, bladder, and urethra as well as male prostate or female reproductive organs.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy drugs used for colorectal cancer treatment are:

- 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), which is often given in combination with leucovorin. Leucovorin is related to a form of B vitamin folic acid. It helps boost the effectiveness of 5-FU. If leucovorin is not available, a related drug, levoleucovorin (Fusilev), is used as an alternative.

- Capecitabine (Xeloda).

- Oxaliplatin (Eloxatin).

- Irinotecan (Camptosar).

- Trifluridine/tipiracil (Lonsurf).

Many of these drugs are given in combination with each other. Common chemotherapy combination regimens include:

- 5-FU / LV (5-FU and leucovorin)

- FOLFOX (5-FU with leucovorin and oxaliplatin)

- FOLFIRI (5-FU with leucovorin and irinotecan)

- FOLFOXIRI (5-FU with leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan)

- CAPOX (Capecitabine and oxaliplatin)

- A biologic drug ("targeted therapy") may be added to some of these regimens

Side effects occur with all chemotherapy drugs and can usually be treated with other medications. Side effects are more severe with higher doses and increase over the course of treatment. Because cancer cells grow and divide rapidly, chemotherapy drugs work by killing fast-growing cells. This means that healthy cells that multiply quickly can also be affected.

Nausea, vomiting, and fatigue are very common side effects. Other side effects can vary depending on the drug used:

- 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) side effects include nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, loss of appetite, hair loss, rashes, mouth sores, and hand-foot syndrome.

- Capecitabine can also cause hand-foot syndrome. This is a skin reaction that appears on the palms of the hands or soles of the feet. It typically begins with feelings of tingling or numbness and progresses to swelling, redness, and pain sensitivity.

- Irinotecan can cause severe diarrhea.

- Oxaliplatin can cause pain and tingling sensations in the hands and feet (neuropathy) that is worsened by exposure to cold.

- Trifluridine/tipiracil (Lonsurf) can cause decreased blood counts.

Targeted therapies work on a molecular level by blocking specific mechanisms associated with cancer cell growth, division, and survival. Traditional chemotherapy drugs can be effective, but because they do not distinguish between healthy and cancerous cells, their generalized toxicity can cause very severe side effects. The drugs used in targeted therapy also cause side effects, but they tend to be less severe in many but not all cases. Targeted therapies have led to longer survivorship in many cases beyond that of chemotherapy.

Targeted biologic antibody drugs approved for colorectal cancer are:

- Bevacizumab (Avastin) and Ziv-Aflibercept (Zaltrap). Anti-angiogenic drugs that target and inhibit vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a protein that regulates angiogenesis (the development of new blood vessels that feed a tumor's blood supply). Bevacizumab is used as a first-line or second-line drug in combination with 5-FU and irinotecan or oxaliplatin. Zif-aflibercept is used along with FOLFIRI (5-FU, leucovorin, irinotecan) as a second-line treatment. These drugs are given by intravenous infusion.

- Ramucirumab (CYRAMZA). A fully humanized monoclonal antibody that binds to vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR-2).

- Cetuximab (Erbitux) and Panitumumab (Vectibix). Target epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), a protein that fuels cancer cell proliferation. These drugs are given by intravenous infusion. Cetuximab may be used in combination with the FOLFOX regimen. Panitumumab may be used along with the FOLFIRI regimen. These drugs may also be used alone. Guidelines recommend that cetuximab, and panitumumab, be administered only for tumors that express the wild-type KRAS gene.

A drug targeting tumor cell machinery approved for colorectal cancer is:

- Regorafenib (Stivarga). A multi-kinase inhibitor that blocks several enzymes involved with cancer cell growth. Unlike other biologic drugs used for colorectal cancer treatment, regorafenib is a pill that is taken by mouth.

Drugs targeting the immune system that are approved for colorectal cancer are:

- Pembrolizumab (Keytruda). Pembrolizumab blocks the lymphocyte receptor for a protein called programmed cell death ligand-1 (PD-L1). Cancer cells that have PD-L1 are protected from being attacked by the body's immune system. Pembrolizumab blocks this process and allows lymphocytes to attack the cancer. It can be given to patients with colorectal cancer whose tumors test positive for biomarkers called microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) and mismatch-repair deficient (dMMR).

- Nivolumab (Opdivo)with ipilimumab (Yervoy). This combination of monoclonal antibodies has been FDA approved for metastatic MSI-H or dMMR colorectal cancer that progresses after chemotherapy.

Radiation

Radiation therapy is used more often for rectal cancer than for colon cancer.

Radiation therapy is not a common treatment for colon cancer. The main use for radiation therapy in people with colon cancer is when the cancer has attached to an internal organ or the lining of the abdomen. When this occurs radiation therapy may be used after surgery (adjuvant radiation) to kill any cancer cells that may still remain.

For rectal cancer, radiation therapy is given for various situations:

- It is frequently used before surgery (neoadjuvant radiation) to help shrink the tumor and make it easier to remove surgically. Radiation therapy before surgery can also help prevent cancer recurrence in the pelvis. Radiation treatment is often combined with chemotherapy (called chemoradiation therapy). Chemotherapy helps make the radiation treatment more effective.

- Radiation therapy may also be given to help control rectal cancers in people who are not healthy enough for surgery.

- For advanced rectal cancer, radiation therapy may be given to ease (palliate) symptoms, such as intestinal blockage, bleeding, or pain.

Radiation therapy uses external or internal sources of radiation to kill cancer cells:

- External Beam Radiation Therapy. Delivers radiation from a source outside the body. External-beam radiation therapy techniques used for rectal cancer includes Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy (IMRT), which uses computer software and 3-D imaging technology to precisely map the tumor, determine radiation dosage, and focus various intensities of high-energy beams to target the tumor from different angles. External beam radiation therapy is used more often than internal radiation therapy.

- Internal Radiation Therapy. Places radioactive material inside the body close to the tumor. Intraoperative Radiation Therapy (IORT) is used during surgery to deliver a concentrated dose to the site of the tumor removal. Endorectal brachytherapy, which is sometimes used in place of surgery, inserts radioactive "seeds" into the rectum to deliver radiation to the tumor site. NOTE: this is almost never used.

- Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy (SBRT). SBRT works similarly to conventional IMRT, but with higher doses of radiation. The tumor is precisely mapped using CT or MRI ahead of radiotherapy. Very high doses of radiation are then delivered through beams of different radiation intensities aimed at the tumor at different angles. Precise tumor mapping allows for minimal damage to the healthy tissues around the tumor that radiation beams pass through, while precisely delivering radiation to the tumor where the beams converge.

Side effects of radiation may include:

- Skin irritation at the radiation site

- Diarrhea, painful bowel movements, and bloody stool

- Loss of bowel control (bowel incontinence)

- Bladder irritation and painful or urgent urination

- Fatigue

- Nausea

- Sexual dysfunction in men and vaginal irritation in women

Resources

- American Cancer Society -- www.cancer.org

- National Cancer Institute -- www.cancer.gov

- American Society of Clinical Oncology -- www.asco.org

- Cancer.Net -- www.cancer.net

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network -- www.nccn.org

- Colon Cancer Coalition -- coloncancercoalition.org

- Colorectal Cancer Alliance -- www.ccalliance.org

- Find clinical trials -- www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/clinical-trials

References

Araghizadeh, F. Ileostomy, colostomy, and pouches. In: Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ, eds. Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2016: chap 117.

Benson AB, Venook AP, Al-Hawary MM, etl al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Colon Cancer, Version 2.2018. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16(4):359-369. PMID: 29632055 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29632055.

Benson AB, Venook AP, Al-Hawary MM, et al. Rectal Cancer, Version 2.2018, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16(7):874-901. PMID: 30006429 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30006429.

Expert Panel on Gastrointestinal Imaging, Moreno C, Kim DH, Bartel TB, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Colorectal Cancer Screening. J Am Coll Radiol. 2018;15(5S):S56-S68. PMID: 29724427 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29724427.

Kushi LH, Doyle C, McCullough M, et al. American Cancer Society Guidelines on nutrition and physical activity for cancer prevention: reducing the risk of cancer with healthy food choices and physical activity. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(1):30-67. PMID: 22237782 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22237782.

Lawler M, Johnston B, Van Schaeybroeck S, et al. Colorectal cancer. In: Niederhuber JE, Armitage JO, Kastan MB, Doroshow JH, Tepper JE, eds. Abeloff's Clinical Oncology. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 74.

Mahmoud NN, Bleier JIS, Aarons CB, Paulson EC, Shanmugan S, Fry RD. Colon and rectum. In: Townsend CM, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL, eds. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery. 20th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017:chap 51.

Meyerhardt JA, Mangu PB, Flynn PJ, et al. Follow-up care, surveillance protocol, and secondary prevention measures for survivors of colorectal cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline endorsement. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(35):4465-4470. PMID: 24220554 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24220554.

National Cancer Institute website. Colon Cancer Treatment (PDQ®) - Health Professional Version. www.cancer.gov/types/colorectal/hp/colon-treatment-pdq. Updated February 22, 2019. Accessed August 22, 2019.

National Cancer Institute website. Rectal Cancer Treatment (PDQ®) - Health Professional Version. www.cancer.gov/types/colorectal/hp/rectal-treatment-pdq. Updated January 29, 2019. Accessed August 22, 2019.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network website. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Colon cancer. Version 2.2019. www.nccn.org/patients/guidelines/colon/index.html. Updated May 15, 2019. Accessed August 22, 2019.

Rex DK, Boland CR, Dominitz JA, et al. Colorectal Cancer Screening: Recommendations for physicians and patients from the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(7):1016-1030. PMID: 28555630 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28555630.

Robertson DJ, Lee JK, Boland CR, et al. Recommendations on fecal immunochemical testing to screen for colorectal neoplasia: A Consensus Statement by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(5):1217-1237.e3. PMID: 27769517 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27769517.

Rutter MD, Beintaris I, Valori R, et al. World Endoscopy Organization Consensus Statements on Post-Colonoscopy and Post-Imaging Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(3):909-925.e3. PMID: 29958856 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29958856.

Sepulveda AR, Hamilton SR, Allegra CJ, et al. Molecular biomarkers for the evaluation of colorectal cancer: Guideline Summary From the American Society for Clinical Pathology, College of American Pathologists, Association for Molecular Pathology, and American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(5):333-337. PMID: 28350513 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28350513.

Smith RA, Andrews KS, Brooks D, et al. Cancer screening in the United States, 2017: A review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and current issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(2):100-121. PMID: 28170086 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28170086.

US Preventive Services Task Force, Davidson KW, Barry MJ, Mangione CM, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325(19):1965-1977. PMID: 34003218 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34003218/.

Wolf AMD, Fontham ETH, Church TR, et al. Colorectal cancer screening for average-risk adults: 2018 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(4):250-281. PMID: 29846947 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29846947.

Reviewed By: Todd Gersten, MD, Hematology/Oncology, Florida Cancer Specialists & Research Institute, Wellington, FL. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team. Editorial update 08/02/2021.