Back pain and sciatica - InDepth

Highlights

Back pain can be acute, subacute, or chronic:

- Acute back pain develops suddenly

- Sub-acute back pain lasts up to 3 months

- Chronic back pain lasts longer than 3 months

Back pain can result from a wide variety of conditions, including:

- Injury

- Sciatica

- Herniated disk

- Lumbar degenerative joint disease

- Spinal stenosis

- Spondylolisthesis

- Inflammatory arthritis

- Compression fracture

- Tumor

- Other conditions (e.g., infections, cancer, gallstones, etc.)

In most known cases, back pain begins with an injury; however, there are some factors that increase the chance of experiencing back pain. These include:

- Aging

- Deconditioning

- High-risk occupations and sports

- Pregnancy

- Psychological and social factors

Usually, a person complaining of back pain will undergo a medical history and a physical examination.

In some cases, other diagnostic techniques may be required. These include:

- Imaging (e.g., x-rays, MRI, CT scan)

- Electrodiagnostic tests

- Other tests (e.g., discography, blood test, urine test, etc.)

A home care program is often the first therapy, this may include:

- Over-the-counter (OTC) drugs to relieve pain

- Hot and cold packs

- Supportive belts and braces

- Rest and sleep

- Quitting smoking

- An exercise regimen (for chronic back pain)

There is a wide variety of medications that can be used to treat back pain. These include:

- Acetaminophen

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- Opioid pain relievers

- Steroid injections

- Antidepressants

- Muscle relaxants

Exercise does not help acute back pain. However, it can help reduce chronic back pain by:

- Increasing flexibility

- Building endurance

- Strengthening the muscles that support the spine and abdomen

Some people use complementary and alternative treatments to relieve back pain, including:

- Acupuncture

- Massage therapy

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy

- Spinal manipulation

- Electric stimulation

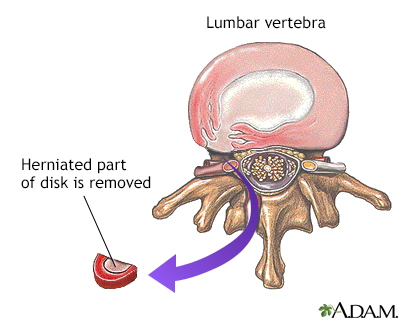

People should generally try all possible non-surgical treatments before opting for surgery. The most common reasons for surgery for low back pain are disk herniation and spinal stenosis. The surgical and invasive procedures used to manage back pain include:

- Diskectomy

- Micro-diskectomy

- Laminectomy

- Spinal fusion

- Other procedures (e.g., percutaneous vertebroplasty, percutaneous kyphoplasty)

Most people with acute low back pain are back at work within a month and fully recover within a few months.

Introduction

Back pain is one of the most common reasons people visit their doctor. According to the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, 25% of adults have at least a day of back pain during a typical 3 months period. Back pain can occur in any area of the back, but it most often involves the lower back.

Back pain can be acute, subacute, or chronic:

- Acute back pain develops suddenly. For most people, the acute pain goes away within a few weeks. Acute back pain is the most common type of back pain.

- Subacute back pain is pain that lasts up to 3 months.

- Chronic back pain can begin abruptly or gradually, linger, subside, then come back, but it lasts longer than 3 months. About 5% to 10% of these people will develop back pain that will persist throughout life.

The spine is highly complex. Pain may result from damage or injury to any of its various bones, nerves, muscles, ligaments, and other structures.

Vertebrae

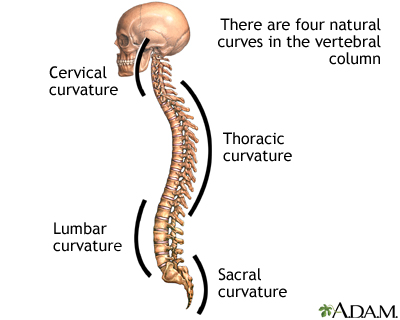

The spine is a column of small bones, or vertebrae, that support the upper body. The column is grouped into 3 sections:

- The cervical (C) vertebrae are the 7 spinal bones that support the neck.

- The thoracic (T) vertebrae are the 12 spinal bones that connect to the rib cage.

- The lumbar (L) vertebrae are the 5 lower bones of the spinal column. A lot of the body's weight and stress falls on the lumbar vertebrae.

Below the lumbar region is the sacrum, a shield-shaped bony structure formed by fusion of 5 sacral (S) vertebrae. The sacrum connects with the pelvis at the sacroiliac joints.

At the end of the sacrum are 3 to 4 tiny, partially fused coccygeal vertebrae known as the coccyx, or "tail bone."

Each vertebra is designated by using a letter and number, allowing the doctor to determine where it is in the spine.

The letter reflects the spinal region where the vertebra is located:

- C=cervical (neck region)

- T= thoracic (chest, or middle back, region)

- L=lumbar (lower back)

The number signifies the vertebra's place within that spinal region. The numbers start with 1 at the top of a region and count up as the vertebrae descend within the region. For example, C4 is the 4th bone down in the cervical region, and T8 is the 8th thoracic vertebrae.

The Disks

Vertebrae in the spinal column are separated from each other by small cushions of cartilage known as intervertebral disks. The disks have no blood supply of their own. They rely on nearby blood vessels to keep them nourished.

Each disk is 80% water and contains two structures:

- Inside each disk is a central jelly-like substance called the nucleus pulposus.

- The nucleus pulposus is surrounded by a tough, fibrous ring called the annulus.

Processes

Each vertebra in the spine has a number of bony projections called processes. The spinous and transverse processes attach to the muscles in the back and act like little levers, allowing the spine to twist or bend. The particular processes form the joints between the vertebrae themselves, meeting together and interlocking at the zygapophysial joints (more commonly known as facet joints, or z-joints).

Spinal Canal

Each vertebra and its processes surround and protect an arch-shaped central opening. These arches, aligned to run down the spine, form the spinal canal, which encloses the spinal cord.

Spinal Cord

The spinal cord is the central trunk of nerves that connect the brain with the rest of the body. Each nerve root passes from the spinal column to other parts of the body through small openings, bounded on one side by the disk and on the other by the facets. When the spinal cord reaches the lumbar region, it splits into multiple bundled strands of nerve roots called the cauda equina (meaning horsetail in Latin).

Symptoms and Causes

The origin of the pain is often unknown, and diagnostic imaging may fail to determine its cause. Disk disease, spinal arthritis, and muscle spasms are the most common diagnoses. However, other problems can also cause back pain.

Strain and injury to the muscles and ligaments supporting the back are the major causes of low back pain. The pain is typically more spread out in the muscles next to the spine and may be associated with spasms in those muscles. The pain may move to the buttocks but rarely any farther down the leg.

The sciatic nerve is a large nerve that starts in the lower back.

- It forms near the spine and is made up from branches of the roots of the lumbar spinal nerves.

- It travels through the pelvis and then deep into each buttock.

- It then travels down each leg. It is the longest and widest single nerve in the body.

Sciatica is not a diagnosis but a description of symptoms. Anything that places pressure on one or more of the lumbar nerve roots can cause pain in parts or all of the sciatic nerve. A herniated disk, spinal stenosis (narrowing of the spinal canal), degenerative disk disease, spondylolisthesis, or other abnormalities of vertebrae can all cause pressure on the sciatic nerve.

Some cases of sciatica pain may occur when the piriformis, a muscle located deep in the buttocks, pinches the sciatic nerve, resulting in a condition called piriformis syndrome. Piriformis syndrome usually develops after an injury or change in activities. It is sometimes difficult to diagnose.

Symptoms of sciatica can include tingling, numbness, or pain that radiates to the buttocks, legs, and feet. Symptoms can vary widely ranging from a mild tingling, dull ache, to a burning sensation. In some cases, the pain is severe enough to cause immobility. The pain most often occurs on one side and may radiate to the buttocks, legs, and feet. The affected leg may feel weak or cold. The pain often starts slowly.

Sciatica pain may get worse:

- At night

- After standing or sitting for long periods of time

- When sneezing, coughing, or laughing

- After bending backward or walking more than 50 to 100 yards (45 to 90 meters) (particularly if it is caused by spinal stenosis -- see below)

Sciatica pain usually goes away within 6 weeks, unless there are serious underlying conditions. Pain that lasts longer than 30 days, or gets worse with sitting, coughing, sneezing, or straining may indicate a longer recovery. Depending on the cause of the sciatica, symptoms may come and go.

A herniated disk, sometimes (incorrectly) called a slipped disk, is a common cause of severe back pain and sciatica. A disk in the lumbar area becomes herniated when it ruptures or thins out and degenerates to the point that the gel within the disk (the nucleus pulposus) pushes outward. The damaged disk can take on many forms:

- A bulge. The gel has been pushed out slightly from the disk and is evenly distributed around the circumference.

- Protrusion. The gel has pushed out slightly and asymmetrically in different places.

- Extrusion. The gel balloons extensively into the area outside the vertebrae or breaks off from the disk.

In cases of herniated disks, the pain in the leg may be worse than the actual back pain. There is also some debate about how pain develops from a herniated disk and how frequently it causes low back pain. Many people have disks that bulge or protrude and do not suffer back pain. Extrusion (which is less common than the other 2 conditions) is much more likely to cause back pain, since the gel extends out far enough to press against the nerve root, most often the sciatic nerve. Extrusion is very uncommon.

Abnormalities in the Annular Ring

The annular ring (the fibrous band that surrounds and protects the nucleus of the disk) contains a dense nerve network and high levels of peptides that heighten perception of pain. Tears in the annular ring are a frequent finding in people with degenerative disk disease.

Cauda Equina Syndrome

Cauda equina syndrome is the compression of the cauda equina (the small 4 strands of nerves leading through the lowest part of the spine). The cause is usually massive extrusion of the disk material. Cauda equina syndrome is an emergency condition that can cause severe complications to bowel or bladder function. It can cause permanent incontinence if not promptly treated with surgery. Symptoms of the cauda equina syndrome include:

- Dull back pain

- Weakness or numbness in the buttocks -- in the area between the legs, or in the inner thigh, backs of legs, or feet -- may cause stumbling or difficulty in standing

- An inability to control urination and defecation

- Pain accompanied by fever (can indicate an infection)

Osteoarthritis occurs in joints of the spine, usually as a result of aging, but also in response to previous back injuries, excessive wear and tear, previously herniated disks, prior surgeries, and fractures. Cartilage between the joints of the spine is destroyed and extra bone growth or bone spurs develop. Spinal disks dry out and become thinner and more brittle. The rate at which these changes develop varies between people.

The end result of these changes is a gradual loss of mobility of the spine and narrowing of the spaces for spinal nerves and spinal cord, eventually leading to spinal stenosis. Symptoms may be similar to that of a herniated disk or spinal stenosis.

Spinal stenosis is the narrowing of the spinal canal, or narrowing of the openings (called neural foramina) where spinal nerves leave the spinal column. This condition typically develops as a person ages and the disks become drier and start to shrink. At the same time, the bones and ligaments of the spine swell or grow larger due to arthritis and long-term (chronic) inflammation. However, other problems, including infection and birth defects, can sometimes cause spinal stenosis.

Most people will report the presence of gradually worsening history of back pain over time. For others, there may be minimal history of back pain, but at some point in this process any disruption, such as a minor injury that results in disk inflammation, can cause impingement on the nerve root and trigger pain.

People may experience pain or numbness, which can occur in both legs, or on just one side. Other symptoms include a feeling of weakness or heaviness in the buttocks or legs. Symptoms are usually present or will worsen only when the person is standing or walking upright. Often the symptoms will ease or disappear when sitting down or leaning forward. These positions may create more space in the spinal canal, thus relieving pressure on the spinal cord or the spinal nerves. People with spinal stenosis are usually not able to walk for long periods of time, but they may be able to ride a bicycle with little pain.

Spondylolisthesis occurs when one of the lumbar vertebrae slips over another, or over the sacrum.

In children, spondylolisthesis usually occurs between the 5th bone in the lower back (lumbar vertebra) and the 1st bone in the sacrum area (L5-S1). It is often due to a birth defect in that area of the spine. In adults, the most common cause is degenerative disease (such as arthritis). The slip usually occurs between the 4th and 5th lumbar vertebrae (L4-L5). It is more common in adults over age 65 years and women.

Other causes of spondylolisthesis include stress fractures (typically seen in gymnasts) and traumatic fractures. Spondylolisthesis may occasionally be associated with bone diseases.

Spondylolisthesis may vary from mild to severe. It can produce increased lordosis (swayback), but in later stages may result in kyphosis (roundback) as the upper spine falls off the lower spine.

Symptoms may include:

- Lower back pain

- Pain in the thighs and buttocks

- Stiffness

- Muscle tightness

- Tenderness in the slipped area

Pain generally occurs with activity and is better with rest. Neurological damage (leg weakness or changes in sensation) may result from pressure on nerve roots, and may cause pain radiating down the legs.

Inflammatory disorders and arthritis syndromes can produce inflammation in the spine. Rheumatoid arthritis can involve the cervical spine (neck). In addition, a group of disorders called seronegative spondyloarthropathies may cause back pain. These include:

- Ankylosing spondylitis. A long-term (chronic) inflammation of the spine that may gradually result in a fusion of vertebrae. The back is usually stiff and painful in the morning; pain improves with movement or exercise. In most cases, symptoms develop slowly over time. In severe cases, symptoms become much worse over a short period of time, and the person develops a stooped over posture. It occurs mostly in young Caucasian men in their mid-20s, and in most cases the cause is believed to be hereditary.

- Reactive arthritis or Reiter syndrome. A group of inflammatory conditions that involve certain joints, the lower back, urethra, and eyes. There may also be sores (lesions) on the skin and mucus membranes.

- Psoriatic arthritis. Found in about 20% of people with psoriasis who develop arthritis involving the spine, as well as many other joints.

- Enteropathic arthritis. A type of arthritis associated with inflammatory bowel disease, such as ulcerative colitis or Crohn disease. About 20% of people with inflammatory bowel disease develop symptoms in the spine.

There are multiple medical treatments for these potentially disabling diseases, and in most cases surgery is not beneficial.

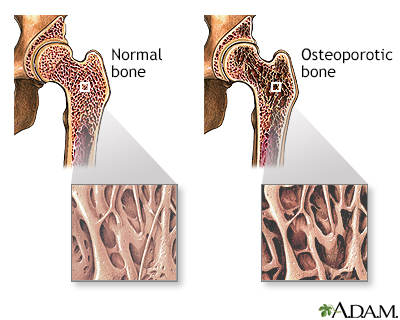

Osteoporosis is a disease of the skeleton in which the amount of calcium present in the bones slowly decreases to the point where the bones become fragile and prone to fractures. It usually does not cause pain unless the vertebrae collapse suddenly, in which case the pain is often severe. More than one vertebra may be affected.

In a compression fracture of the vertebrae, the bone tissue of the vertebra collapses. More than one vertebra may collapse as a result. When the fracture is the result of osteoporosis, the vertebrae in the thoracic (chest) and lower spine are usually affected, and symptoms may be worse with walking.

With multiple fractures, kyphosis (a forward hump-like curvature of the spine) may result. In addition, compression fractures are often responsible for loss of height. Pressure on the spinal cord may also occur, producing symptoms of numbness, tingling, or weakness. Symptoms depend upon the area of the back that is affected. However, most fractures are stable and do not produce neurological symptoms.

Several serious conditions can also cause back pain. Often, these symptoms develop over a short period of time, become more severe, and may have other findings that go along with them. Some of these conditions include:

- Infection in the bone (osteomyelitis) or the disk (diskitis).

- Infection in the spinal canal (epidural abscess).

- Cancer that has spread to the spine from another part of the body (most commonly metastases from lung cancer, colon cancer, prostate cancer, and breast cancer).

- Cancer that begins in the bones (the most common diagnosis in adults is probably multiple myeloma, seen in middle age or older adults). Benign tumors such as osteoblastoma or neurofibroma and cancers, including leukemia, can also cause back pain in children.

- Trauma.

Other causes of back pain include:

- Fibromyalgia and other myofascial pain syndromes.

- Other medical conditions that cause referred back pain, occurring in conjunction with problems in organs unrelated to the spine (although usually located near it); such conditions include ulcers, kidney disease (including kidney stones), ovarian cysts, and pancreatitis.

- Long-term (chronic) uterine or pelvic infections can cause low back pain in women.

Risk Factors

In most known cases, pain begins with an injury, after lifting a heavy object, or after making a sudden movement. However, not all people have back pain after such injuries. In the majority of back pain cases, the triggers are unknown.

Intervertebral disks begin deteriorating and growing thinner by age 30. One-third of adults over age 20 years show signs of herniated disks (although only 3% of these disks cause symptoms). As people continue to age and the disks lose moisture and shrink, the risk for spinal stenosis increases. The incidence of low back pain and sciatica increases in women at the time of menopause as they lose bone density. In older adults, osteoporosis and osteoarthritis are also common. However, the risk for low back pain does not mount steadily with increasing age, which suggests that at a certain point, the conditions causing low back pain plateau.

Jobs that involve lifting, bending, and twisting into awkward positions, as well as those that cause whole-body vibration (such as long-distance truck driving), place workers at particular risk for low back pain. The longer a person continues such work, the higher their risk. Some workers wear back support belts, but evidence strongly suggests that they are useful only for people who currently have low back pain. The belts offer little added support for the back and do not prevent back injuries. Sports with repetitive stress on the back can also cause back problems. Impact sports such as football and basketball and repetitive sports such as gymnastics can also cause back problems.

A number of companies have programs to protect against back injuries -- with mixed results. Employers and workers should make every effort to create a safe working environment. Office workers should have chairs, desks, equipment that support the back, standing desks, or help maintain good posture.

Osteoporosis is a condition characterized by progressive loss of bone density, thinning of bone tissue, and increased vulnerability to fractures. Osteoporosis may result from disease, dietary or hormonal deficiency, or advanced age. Regular exercise and vitamin and mineral supplements can reduce and even reverse loss of bone density.

Persistent low back pain in children is more likely to have a serious cause that requires treatment than back pain in adults.

Stress Fractures (Spondylolysis)

Stress fractures in the spine are a common cause of back pain in young athletes. Sometimes a fracture may not show up for a week or two after an injury. Spondylolysis can cause spondylolisthesis. These usually occur in athletes that do repetitive activities, like training.

Hyperlordosis

Hyperlordosis is an inborn exaggerated inward curve in the lumbar area. Scoliosis, an abnormal curvature of the spine in children, does not usually cause back pain.

Juvenile Chronic Arthropathy

This is an inherited form of arthritis. It can cause pain in the sacrum and hip joints of children and young people. Formerly grouped under juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, it is now defined as a separate problem.

Injuries can also cause back pain in children.

Pregnant women are prone to back pain due to a shifting of abdominal organs, increase stress because of weight gain, the forward redistribution of body weight, and the loosening of ligaments in the pelvic area as the body prepares for delivery. Tall women are at higher risk than short women.

Psychological and social factors can also play a role in low back pain:

- Pre-existing depression and the inability to cope may be more likely to predict the onset of pain than physical problems. A "passive" coping style (not wanting to confront problems) was strongly associated with the risk of developing disabling neck or low back pain.

- Social and psychological factors, as well as job satisfaction, all play a role in the severity of a person's perception of back pain and back-related absenteeism from work.

- Depression and a tendency to develop physical complaints in response to stress also increase the likelihood that acute back pain will become a long-term (chronic) condition. The way a person perceives and copes with pain at the beginning of an acute attack may influence whether the person recovers fully or develops a chronic condition. Those who over-respond to pain and fear for their long-term outlook tend to feel out of control and become discouraged, increasing their risk for long-term problems.

People who reported prolonged emotional distress have less favorable outcomes after back surgeries. It should be strongly noted that the presence of psychological factors in no way diminishes the reality of the pain and its disabling effects. Recognizing this presence as a strong player in many cases of low back pain, however, can help determine the full range of treatment options.

Diagnosis

Even though acute back pain and flare-ups of chronic back pain may resolve by themselves, a medical history and a brief physical examination are still usually performed. And depending on the severity of the symptoms, how long they have been present, and any associated medical problems, additional evaluations may be necessary.

The person should be able to describe the back pain and its history in the following manner:

- Frequency, duration, and nature of the pain

- When the pain occurs

- What triggered the pain (such as lifting a heavy object)

- Conditions that make the pain worse, such as coughing

- Other relevant symptoms, such as morning stiffness, weakness, or numbness in the legs

- Previous episodes of back pain

- Previous back procedure or epidural

- Severity of the pain and how it affects the person's ability to perform everyday activities or work activities

- Any situation that relieves the pain

- Any history of injuries or accidents involving the neck, back, or hips

- Other medical conditions, such as arthritis or osteoporosis

A person should report any serious health problems, symptoms, and concerns that may raise a red flag for a more serious condition. These include:

- HIV infection or AIDS

- Pain that is increasing in intensity and cannot be relieved

- Pain that increases when lying down

- Fever that is associated with the back pain

- Any new or worsening neurological symptoms, such as weakness in a specific part of the legs or feet

- History of cancer, or currently being treated for cancer

- Problems emptying the bowels or bladder, including incontinence

- Unexplained weight loss

Special state guidelines should be followed for worker's compensation patients.

The main goals of a physical exam are to determine the source of the pain, the limits of movement and to detect signs of a more serious back condition. The physician will observe the person's posture and gait, visually inspect and palpate the back, and perform movement and other tests.

- People may be asked to sit, stand, and walk in different ways (flat-footed, on the toes, and on their heels).

- People may be requested to bend forward, backward, and sideways and to twist.

- People may be asked to lift their leg straight up while lying down. The health care provider may also move the person's legs in different positions and bend and straighten the knees. (Pain caused by sciatica can be intensified by lifting the affected leg straight in the air. It is usually sharp, localized, and accompanied by numbness or tingling. Pain caused by inflammation is duller and more generalized and not affected by lifting a straight leg.)

- The provider may measure the circumference of the calves and thighs to look for muscle wasting.

- To test nerve function and reflexes, the provider may tap the knees and ankles with a rubber hammer. The provider may also touch parts of the body lightly with a pin, cotton swab, or feather to test for numbness and nerve sensitivity.

- The provider may assess strength in different muscle groups of the legs.

- If there is concern about more serious spinal problems, a rectal examination may be needed to check for more severe problems.

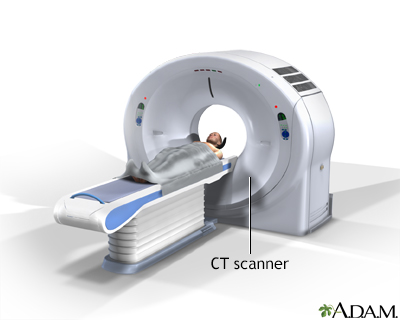

Imaging tests used to evaluate back pain range from a simple x-ray to a CT scan or MRI of the spine. Depending on medical diagnoses that are identified by the history, the person may need such tests as a dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan for osteoporosis or a nuclear scan for suspected arthritis, cancer, or infection.

Because most people with new back pain are on the mend or completely recover within 6 weeks, imaging techniques such as x-rays or scans are rarely recommended early in the course of back pain. Doing so does not improve outcomes, unless a serious underlying condition is suspected.

People who have the following symptoms or experience certain events may need more sophisticated imaging:

- Significant pain that lasts more than 1 to 2 months

- Symptoms such as pain, numbness, or tingling extending from the buttocks down the leg that are very severe or are getting worse

- Muscle weakness that is significant, persistent, or getting worse

- A previous accident or injury that might have affected the disks or vertebrae

- A history of cancer

- Indications of an underlying disease such as fever or unexplained weight loss

- New pain that occurs in people over 65 years of age. Pain that increases when lying down

- Other red flag symptoms noted above

- Difficulty controlling your bladder and bowels

Even when symptoms last longer, unless a potentially serious diagnosis is suspected, MRI or CT scans can often be delayed until the time when surgery or epidural steroid injections come into consideration as treatment options.

X-Rays

X-ray examination provides useful information on bone structure and pathology, and may help diagnose underlying conditions such as fractures, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, tumors, and others. However, x-rays are not useful for detecting soft tissue abnormalities such as herniated disks, for which CT and MRI are more appropriate. X-rays are typically not recommended in the first 6 weeks of low back pain.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can provide very well-defined images of soft tissue and bone. The test is not painful or dangerous, but some people may feel claustrophobic in scanners where they are fully enclosed. MRIs can detect tears in the disks, disk herniation, or disk fragments. It can also detect spinal stenosis and non-spinal causes of back pain, including infection and cancer.

MRI scans often detect spine abnormalities that are not causing symptoms in the person. Almost half of all adults have bulging or protruding vertebral disks, and most have no back pain. And, the degree of disk abnormalities revealed by MRIs often has very little to do with the severity of the pain or the need for surgery. Disk abnormalities in people who have back pain may simply be normal age appropriate changes rather than an indication for treatment.

People are also more likely to think of themselves as having a serious back problem if abnormalities are identified on MRI scans, even if the scans do not result in treatment changes. This perception may sometimes slow down their recovery.

Computerized Tomography (CT) Scan

In this procedure, a thin x-ray beam is rotated around the area of the body to be visualized. Using very complicated mathematical processes called algorithms the computer is able to generate a 3-D image of a section through the body. CT scans are very detailed and provide excellent information for the doctor regarding your bone structures. It is a shorter test when compared with the MRI scan.

Bone Scintigraphy and SPECT Imaging

In rare cases, doctors may use bone scintigraphy (bone scanning) to determine abnormalities in the bones. The technique may be useful for early detection of spinal fractures, cancer that has spread to the bone, or certain inflammatory arthritic conditions. During this exam, a small amount of radioactive material is injected into a vein. It circulates through the body, and is absorbed by the bones. The bones can then be seen using x-rays or single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT).

X-ray Myelogram

This technique is an x-ray of the spine that requires a spinal injection of a special dye and the need to lie still for several hours to avoid a very painful headache. It has value only for select people with pain on moving and standing. It has largely been replaced by CT and MRI scans.

Tests that analyze the electric waveforms of nerves and muscles may be useful for detecting nerve abnormalities that may be causing back pain and identifying possible injuries. They are also useful to determine if any abnormal structural findings on an MRI or other imaging tests have real significance as a cause of back pain. It should be noted that any nerve injuries that affect these tests may not be present for 2 to 4 weeks after symptoms begin.

Nerve conduction tests and electromyography are the electrodiagnostic tests most commonly performed. These tests are not used often in the evaluation and management of people with low back pain.

Diskography

Since many people have evidence of disk degeneration on their MRI scans, it is not always easy to tell if the finding on this MRI scan explains pain the person may be experiencing. Diskography is a test that is used to help determine whether an abnormal disk seen on MRI explains someone's pain. It is generally reserved for people who did not experience relief from other therapies, including surgery. This procedure requires injections into disks suspected of being the source of pain and disks nearby. This is performed under guidance of imaging and is painful. It can be painful. There is controversy among physicians who take care of the spine regarding the usefulness of diskography for making decisions about care, particularly surgery. The American Pain Society is against the use of provocative diskography for people with chronic non-radicular (pain that does not radiate) low back pain.

Blood and urine samples may be used to test for infections, arthritis, or other conditions.

Injecting a drug that blocks pain into the nerves in the back helps locate the level in the spine where problems occur.

A procedure called a facet block is also useful in locating areas of specific damage.

Self-Care

A conservative home care program is often the first therapy regimen for new back pain (unless the doctor suspects a serious underlying condition). The goals are to reduce any swelling and improve function. The regimen often includes period of rest and movement, the application of ice or heat, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and gentle exercises. A work ergonomics assessment may also be beneficial.

- Resume normal activity as soon as tolerated. Bed rest is no longer recommended and may delay recovery. Rest only periodically, as you normally would, or while applying ice or heat. Activities should be done without strain or stretching.

- Avoid intense exercise and physical activity, particularly heavy lifting and trunk twisting, if there is acute back pain.

- Try an over-the-counter (OTC) NSAID such as aspirin or ibuprofen, or an analgesic such as acetaminophen. These medicines often provide significant benefits.

- Apply heat (about 104°F [40°C]) to the painful area.

- Try alternating between hot and cold packs. Some doctors recommend changing from hot to cold every 3 minutes and repeating this sequence 3 times. Others believe ice packs should be applied first. This routine should be done 2 or 3 times during the day. (Note: Heat or cold treatments do not have much effect on sciatica.)

- Supportive back belts, braces, or corsets may help some people temporarily, but these products can reduce muscle tone over time and should be used only briefly.

- Get plenty of sleep. Healthy sleep plays a vital role in recovery. Avoid caffeine in the afternoon and evening and unwind before bed by taking a warm bath or practicing relaxation techniques. It is often difficult to get a good night's sleep when suffering from back pain, particularly because the pain can intensify at night. Some people may need medicine to help manage nighttime pain or treat sleeplessness. Lying curled up in a fetal position with a pillow between the knees or lying on the back with a pillow under the knees may help.

- Yoga can relieve low back pain better than conventional exercise or self-help books.

- Exercise, diet, stress, and weight all have a significant influence on back pain. Changing certain lifestyle factors can help reduce, and possibly prevent, backaches.

Quit Smoking

Smokers are at higher risk for back problems, perhaps because smoking decreases blood circulation or because smokers tend to have an unhealthy lifestyle in general.

Sedentary Lifestyle

People who do not exercise regularly face an increased risk for low back pain, such as when they perform sudden, stressful activities such as shoveling, digging, or moving heavy items. Although there is no definitive link between lack of exercise and low back pain, some providers believe that an inactive lifestyle may be to blame in some cases. Lack of exercise leads to the following conditions that may threaten the back:

- Stiff muscles can make it hard to move, rotate, and bend the back.

- Weak stomach muscles can increase the strain on the back and cause an abnormal tilt of the pelvis.

- Weak back muscles may increase the risk for disk compression.

- Obesity puts more weight on the spine and increases pressure on the vertebrae and disks.

Improper or Intense Exercise

- Improper or excessive exercise may also increase one's chances for back pain. Studies on the effect of regular high-impact exercise (such as running) on the risk for degenerative disk disease had mixed or contradictory results.

- Between 30% and 70% of cyclists experience low back pain. In some cases, this can be resolved simply by adjusting the angle of the bicycle seat.

- Improper exercise instruction and inattention to body movements can lead to back trouble. For example, a single jerky golf swing or incorrect use of exercise equipment (free weights, nautilus, and rowing machines) can cause serious back injuries.

The way a person moves, stands, or sleeps plays a major role in back pain.

- Maintaining good posture is very important. This means keeping the ears, shoulders, and hips in a straight line with the head up and stomach pulled in. It is best not to stand for long periods of time. If it is necessary, walk as much as possible and wear shoes without heels, preferably with cushioned soles. Use a low foot stool and alternate resting each foot on top of it.

- Sitting puts the most pressure on the back. Chairs should either have straight backs or low-back support. If possible, chairs should swivel to avoid twisting at the waist, have armrests, and adjustable backs. While sitting, the knees should be a little higher than the hip, so a low stool or hassock is useful to put the feet on. A small pillow or rolled towel behind the lower back helps relieve pressure while either sitting or driving.

- Riding in or driving a car for long periods of time increases stress. Move the car seat forward to avoid bending forward. The back of the seat should not be reclined more than 30 degrees. If possible, the seat bottom should be tilted slightly upward in front. A traveler should stop and walk around about every hour. Avoid lifting or carrying objects immediately after the ride.

- A common cause of temporary back pain in children is carrying backpacks that are too heavy. Backpacks should not weigh more than 20% of the child's body weight. They should weigh even less for very young children. Emotional or behavioral problems may also contribute to back pain in children.

Anyone who engages in heavy lifting should take precautions when lifting and bending.

- If an object is too heavy or awkward, get help.

- Spread your feet apart to give yourself a wide base of support.

- Stand as close as possible to the object being lifted.

- Bend at the knees, not at the waist. As you move up and down, tighten stomach muscles and tuck buttocks in so that the pelvis is rolled under and the spine remains in a natural "S" curve. (Even when not lifting an object, always try to use this posture when stooping down.)

- Hold objects close to the body to reduce the load on the back.

- Lift using the leg muscles, not those in the back.

- Stand up without bending forward from the waist.

- Never twist from the waist while bending or lifting any heavy object. If you need to move an object to one side, point your toes in that direction and pivot toward it.

- If an object can be moved without lifting, pull it, do not push.

There are four natural curves in the spinal column: the cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral curvature. The curves, along with the intervertebral disks, help to absorb and distribute stresses that occur from everyday activities such as walking or from more intense activities such as running and jumping.

Medications

The American College of Physicians (ACP) 2017 clinical practice guidelines for treatment of acute and subacute low back pain recommend using non-drug therapies (superficial heat, massage, acupuncture, spinal manipulation). If necessary, these can be combined with select NSAIDs or skeletal muscle relaxants.

For chronic low back pain, the ACP recommends non-drug therapy (such as exercise, rehabilitation, acupuncture, or cognitive behavioral therapy). If people do not respond to non-drug therapy, NSAIDs are used as first line of treatment, and tramadol (an opioid pain medication) or duloxetine (an anti-depressant) as second line of treatment. Opioids should only be considered as a last option for drug treatment due to their high risk for addiction and accidental overdose and should only be prescribed when the benefits are judged to outweigh these significant risks.

Acetaminophen (Tylenol) is a safe and effective pain reliever for mild-to-moderate acute back pain. It is also used to reduce fever. The benefits are usually felt 30 to 60 minutes after ingestion, and it can be taken every 4 to 6 hours. Side effects can include skin rashes or inflammation, and in rare cases, damage to the liver or kidneys. Acetaminophen was not found to be effective against acute back pain, and NSAIDs are preferred.

The most commonly prescribed medications for the treatment of back pain are NSAIDs. Short-term use of NSAIDs may help some people with acute back pain. The benefits of NSAIDs for chronic back pain are less certain.

There are dozens of available NSAIDs:

- Over-the-counter (OTC) NSAIDs include aspirin, ibuprofen (Motrin IB, Advil, Nuprin, Rufen), naproxen (Aleve), ketoprofen (Actron, Orudis KT).

- Prescription NSAIDs include ibuprofen (Motrin), naproxen (Naprosyn, Anaprox), flurbiprofen (Ansaid), diclofenac (Voltaren), tolmetin (Tolectin), ketoprofen (Orudis, Oruvail), dexibuprofen (Seractil), and celecoxib (Celebrex).

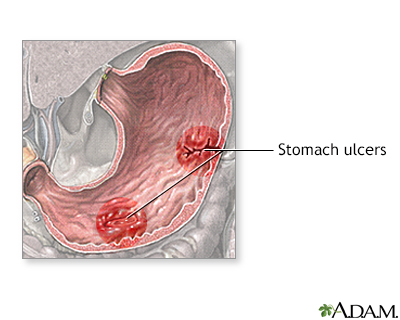

While widely available and generally safe for most people when used on a short-term basis, long-term use of these drugs carries several side effects. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued "black box" warnings, the FDA's strongest, around risks for heart disease, ulcers, and gastrointestinal bleeding:

- Heart disease. These drugs may raise the risk of a heart attack or stroke. This risk is probably higher with long-term, regular use, such as for people who have a heart condition.

- Upset stomach. Dyspepsia (burning bloated feeling in pit of stomach) is a common symptom. Taking NSAIDs with food can reduce stomach discomfort, although it may slow down the pain-relieving effect.

- Ulcers and gastrointestinal bleeding. Long-term use of NSAIDs is also the second most common cause of ulcers and gastrointestinal bleeding.

Those at highest risk for bleeding include people over age 60, anyone with a history of ulcers or gastrointestinal bleeding, people with serious heart conditions, people who abuse alcohol, and those who take medications such as anticoagulants (blood thinners) and corticosteroids.

Proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) drugs may help prevent and heal ulcers caused by NSAIDs. PPIs include omeprazole (Prilosec), esomeprazole (Nexium), and lansoprazole (Prevacid).

To reduce the risks associated with NSAIDs, take the lowest dose possible for pain relief. Always talk with your provider before using any of these drugs on a regular basis.

Other possible side effects of NSAIDs may include:

- Drowsiness

- Skin bruising

- High blood pressure

- Fluid retention leading to leg swelling

- Headache

- Liver damage

- Rash

- Reduced kidney function

An ulcer is a crater-like lesion on the skin or mucous membrane that is caused by an inflammatory, infectious, or cancerous condition. To avoid irritating an ulcer, stop smoking and try to eliminate certain substances from your diet, including caffeine and alcohol. Prescription medicines are available to suppress the acid in the stomach that causes erosion of the stomach lining. Endoscopic therapy can be used to stop ulcer-related bleeding.

Narcotics are pain-relievers that act on the central nervous system. They are the most powerful medications available for the management of pain.

There are two types of narcotics:

- Opioids derived from natural opium (also called opiates), such as morphine and codeine, are substances naturally found in the opium poppy plant.

- Synthetic opioids are drugs that mimic the effects of opiates and include oxycodone (Percodan, Percocet, OxyContin), hydrocodone (Vicodin), tramadol (Ultram), fentanyl (Duragesic) and oxymorphone (Numorphan).

Opioids are effective for short-term relief of back pain. Using them for long periods is strongly associated with risk of abuse and addiction.

Common side effects of opioids include anxiety, constipation, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, drowsiness, paranoia, urinary retention, restlessness, and labored or slow breathing. Opioid abuse and addiction is a major concern associated with the use of opioids. Unless the pain is very severe, experts advise against routinely prescribing opioids. The current guidelines from the ACP recommend that clinicians should only consider opioids if the following conditions apply:

- People have failed treatments with other drugs (NSAIDs)

- The benefits of such treatment outweigh the risks

- The known risks and realistic benefits expectations were discussed with the person

Injections of corticosteroids (commonly called steroids) are sometimes used to treat low back pain caused by nerve impingement. The injection is placed into the epidural space, just inside the outer membrane covering the spine.

The injection is directed as close to the location of the affected nerve as possible. Corticosteroids reduce inflammation.

The evidence that steroid injections help with sciatica or low back pain is conflicting.

People may experience short-term pain relief, generally over a 1 to 2 month period, from these injections. The amount of relief varies and most often is not long-lasting. Receiving epidural injections does not decrease the chance of needing surgery in the future.

The American Pain Society's (APS) guidelines on injection therapy stress shared decision making between doctor and person. It concludes that corticosteroid injection, prolotherapy (a sugar water injection that causes temporary inflammation and increased blood flow) and intradiscal corticosteroid injections should not be performed on people with nonradicular (non-radiating) low back pain. The APS recommends a thorough discussion of the risks, possible short-term benefits and lack of evidence for people with radiculopathy (nerve root damage) due to herniated disk.

Serious and painful side effects, including meningitis and inflammation, are possible. However, such risks are very low.

Epidural steroid injections for spinal stenosis may provide short-term relief of pain but generally do not improve the person's daily functioning, nor do they help people avoid surgery.

Antidepressants may lessen the severity of pain in certain people with chronic back pain, but they should not be used routinely. More information is necessary to determine which people would benefit from antidepressant medication for low back pain.

Antidepressants called tricyclics may be effective in non-depressed people with chronic back pain. Such antidepressants include amitriptyline (Elavil, Endep), desipramine (Norpramin), doxepin (Sinequan), imipramine (Tofranil), amoxapine (Asendin), nortriptyline (Pamelor, Aventyl), and maprotiline (Ludiomil). Tricyclics can have bothersome and rarely dangerous side effects.

Another antidepressant medication, duloxetine hydrochloride (Cymbalta), has been approved for the treatment of lower back pain. Side effects may include nausea, dry mouth, insomnia, drowsiness, constipation, fatigue, and dizziness. More serious side effects are rare.

Combining antidepressant medications with a pain self-management program or some type of cognitive-behavioral therapy often adds to the benefit in back pain people who are also depressed. A combined therapy approach, including antidepressant therapy and pain self-management, has been shown to improve depression symptoms and reduce the severity of pain and disability.

A combination of NSAIDs and muscle relaxants -- such as cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril), diazepam (Valium), carisoprodol (Soma), or methocarbamol (Robaxin) -- are sometimes used for people with acute low back pain. Evidence has shown that they can help relieve non-specific low back pain, but some experts warn that these drugs should be used cautiously, since they target the brain, not the muscles. People who take muscle relaxants may experience a number of central nervous system side effects, such as drowsiness. The muscle relaxant Soma can be addictive and does little more than induce sleep.

Exercise and Physical Therapy

Physical therapy with a trained professional may be useful if pain has not improved after 3 to 4 weeks. It is important for any person who has chronic low back pain to have an exercise program. Professionals who understand the limitations and special needs of people with back pain, and can address individual health conditions, should guide this program.

Physical therapy typically includes the following:

- Education and training the person in correct movement

- Exercises to help the person keep the spine in neutral positions during all daily activities

- Exercises to strengthen the back and abdominal muscles to better support the spine

Incorrect movements or long-term high-impact exercise is often a cause of back pain in the first place. People vulnerable to back pain should avoid activities that put undue stress on the lower back or require sudden twisting movements, such as football, golf, ballet, and weight lifting.

Specific and regular exercise under the guidance of a trained professional is important for reducing pain and improving function, although people often find it difficult to maintain therapy.

Exercise does not help acute back pain. In fact, overexertion may cause further harm. Beginning after 4 to 8 weeks of pain, however, a rehabilitation program may benefit the person.

An incremental aerobic exercise program (such as walking, stationary biking, and swimming) may begin within 2 weeks of symptoms. Jogging is usually not recommended, at least not until the pain is gone and muscles are stronger.

People should avoid exercises that put the lower back under pressure until the back muscles are well toned. Such exercises include leg lifts done in a facedown position, straight leg sit-ups, and leg curls using exercise equipment.

In all cases, people should never force themselves to exercise if, by doing so, the pain increases.

Exercise can help reduce chronic back pain. Repetition is the key to increasing flexibility, building endurance, and strengthening the specific muscles needed to support the spine. Exercise should be considered as part of a broader program to return to normal home, work, and social activities. In this way, the positive benefits of exercise not only affect strength and flexibility but also alter and improve person attitudes toward their disability and pain. Exercise may also be effective when combined with a psychological and motivational program, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy.

There are different types of back exercises. Stretching exercises work best for reducing pain, while strengthening exercises are best for improving function. Graded exercise programs, including daily walks and home and workplace interventions may improve pain and function for 12 months or longer in people with chronic low back pain.

Weekly yoga and stretching classes can be effective methods to improve function and reduce symptoms.

Exercises for back pain include:

- Low impact aerobic exercises. Low-impact aerobic exercises, such as swimming, bicycling, and walking, can strengthen muscles in the abdomen and back without over-straining the back. Programs that use strengthening exercises while swimming may be a particularly beneficial approach for many people with back pain. Pregnant women who engage in a water gymnastics program may experience less back pain and are able to continue working longer.

- Spine stabilization and strength training. Exercises called lumbar extension strength training are proving to be effective. Generally, these exercises attempt to strengthen the abdomen, improve lower back mobility, strength, and endurance, and enhance flexibility in the hip, the hamstring muscles, and the tendons at the back of the thigh.

- Yoga, Tai Chi, Chi Kung. Practices originating in Asia that combine low-impact physical movements and meditation may be very helpful. They are designed to achieve a physical and mental balance and can be very helpful in preventing recurrences of low back pain.

- Flexibility exercises. Flexibility exercises may help reduce pain. A stretching program may work best when combined with strengthening exercises.

Perform the following exercises at least 3 times a week:

Partial Sit-ups

Partial sit-ups or crunches strengthen the abdominal muscles.

- Keep your knees bent and the lower back flat on the floor while raising the shoulders up 3 to 6 inches (8 to 15 centimeters).

- Exhale on the way up, and inhale on the way down.

- Perform this exercise slowly 8 to 10 times with the arms across your chest.

Pelvic Tilt

The pelvic tilt alleviates tight or fatigued lower back muscles.

- Lie on your back with your knees bent and feet flat on the floor.

- Tighten your buttocks and abdomen so that they tip up slightly.

- Press your lower back to the floor, hold for one second, and then relax.

- Be sure to breathe evenly.

Over time increase this exercise until it is held for 5 seconds. Then, extend your legs a little more so that your feet are further away from your body and try it again.

Stretching Lower-Back Muscles

The following are 3 exercises for stretching the lower back:

- Lie on your back with your knees bent and legs together. Keeping arms at the sides, slowly roll your knees over to one side until totally relaxed. Hold this position for about 20 seconds (while breathing evenly) and then repeat on the other side.

- Lying on your back, hold one knee and pull it gently toward your chest. Hold for 20 seconds. Repeat with your other knee.

- While supported on your hands and knees, lift and straighten your right hand and left leg at the same time. Hold for 3 seconds while tightening your abdominal muscles. Your back should be straight. Alternate with your other arm and leg and repeat on each side 8 to 20 times.

Note: No one with low back pain should perform exercises that require bending over right after getting up in the morning. At that time, the disks are more fluid-filled and more vulnerable to pressure from this movement.

Other Treatments

People use many complementary and alternative treatments to relieve back pain. Complementary means something that is used together with conventional medicine. Alternative means something that is done in place of conventional medicine. Do not start any complementary or alternative treatment without first talking about it with your provider.

Acupuncture is now a common alternative treatment for certain kinds of pain. It involves inserting small needles or exerting pressure on certain points in the body. When the pins have been placed, the person is supposed to experience a sensation that brings a feeling of fullness, numbness, tingling, and warmth with some soreness around the acupuncture point. Most evidence on its benefits is weak and debate continues on whether the placebo effect is a major factor in acupuncture. In any case, it may be helpful for certain people with back pain, such as pregnant women, who must avoid medications. Anyone who undergoes acupuncture should be sure it is performed in a reputable facility by experienced practitioners who use sterilized equipment.

Acupuncture has not shown any benefits for acute low back pain in most people, but it may provide some help for people with chronic low back pain. Organizations such as the American College of Physicians, American Pain Society, North American Spine Society and UK National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence have included acupuncture among possible treatment options for low back pain, particularly for people with chronic low back pain who do not respond well to self-care treatments.

Massage therapy can help some people with chronic or acute back pain, such as when combined with exercise and person education.

A course of cognitive-behavioral therapy can help reduce chronic back pain, or at least enhance the person's ability to deal with it. The primary goal of this form of therapy in such cases is to change the distorted perceptions that people have of themselves, and change their approach to pain. People use specific tasks and self-observations to help them change their thinking. They gradually shift their perception of helplessness against the pain that dominates their lives into the perception that pain is only one negative among many positives and, to a degree, a manageable experience.

- Spinal manipulation is a practice based on the idea that misalignment of vertebrae has negative effects for the function of spine. Chiropractors typically perform spinal manipulations as their main practice focus. Osteopaths (DO) may also use spinal manipulations as one of the treatment options they can provide, but are physicians qualified to fully manage any condition just as an allopath, or medical doctor (MD).

- Spinal manipulation is one of several options to obtain mild to moderate relief for low back pain. Ongoing or maintenance spinal manipulation has not been proven to alter the course of chronic back pain.

Mild and temporary side effects from spinal manipulation are common. There is also a low potential for serious adverse effects from low back manipulation.

Percutaneous Neuromodulation Therapy

A technique called percutaneous neuromodulation therapy (PNT) uses a small device that delivers electrical stimulation to deep tissues and nerve pathways near the spine through the skin.

Electrical Nerve Stimulation

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) uses low-level electrical pulses to suppress back pain. A variant of this procedure, percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (PENS), applies these pulses through a small needle to acupuncture points. Both of these apply the stimulation through the skin.

When tested in high-quality studies, these electrical nerve stimulation techniques have not been found to provide much help for chronic low back pain.

Spinal Cord Stimulation

A more invasive technique involves delivering the electrical impulse through electrodes implanted on or next to the spinal column. It is only considered for people with chronic radicular pain that is still present after surgery and other drug and non-invasive treatments have failed to help. The risks and benefits and high rate of complications of this type of stimulation should be discussed thoroughly with the surgeon.

Radiofrequency Neurotomy

An interventional procedure that involves the use of heat applied to the nerves that carry pain signals. Preliminary research has shown benefits in treating people with back pain in the facet joints on either side of the spine. It may provide benefits in the sacroiliac joints in the lowest part of the spine as well.

Surgery and Invasive Procedures

The provider should give people complete information on the expected course of their low back pain and self-care options before discussing surgery. People should ask their provider about evidence favoring surgery or other (nonsurgical) treatments in their particular case. They should also ask about the long-term outcome of the recommended treatment. Would the improvements last, and if so, for how long? Another consideration when surgery is an option is the overall safety of the recommended procedure, weighed against its potential short-term and long-term benefits.

People should generally try all possible non-surgical treatments before opting for surgery. The vast majority of back pain people will not need aggressive medical or surgical treatments.

The most common reasons for surgery for low back pain are disk herniation and spinal stenosis. In general, surgery has been found to provide better short term and possibly quicker relief for selected people when compared to non-surgical treatment. However, over time, nonsurgical treatments are as effective.

It should be noted that surgery does not always improve outcome and, in some cases, can even make it worse. However, surgery can be an extremely effective approach to certain people with severe back pain that does not respond to other therapies.

Diskectomy or discectomy is the surgical removal of the diseased disk. The procedure relieves pressure on the spine. It has been performed for over age 40 years, and less invasive techniques have been developed over time. In appropriate candidates it provides faster relief than medical treatment, but long-term benefits (over 5 years) are uncertain.

Diskectomy is recommended when a herniated disk causes one or more of the following:

- Leg pain or numbness that are severe or persistent, making it hard for the person to perform daily tasks

- Weakness in the muscles of the lower leg or buttocks

- An inability to control bowel movements or urination

Most other people with low back or neck pain, numbness, or even mild weakness are often first treated without surgery. Often, many of the symptoms of low back pain caused by a herniated disk get better or disappear over time, without surgery.

When the soft, gelatinous central portion of an intervertebral disk is forced through a weakened part of a disk, it is called a herniated disk. Most herniated disks take place in the lumbar area of the spine. Herniated disks are one of the most common causes of lower back pain. The mainstay of treatment is an initial period of rest with pain and anti-inflammatory medications followed by physical therapy. If pain and symptoms persist, surgery to remove the herniated portion of the intervertebral disk may be needed.

Microdiskectomy

Microdiskectomy is the current standard procedure. It is performed through a small incision (1 to 1-1/2 inch [2.5 to 3.8 centimeters]). The back muscles are lifted and moved away from the spine. After identifying and moving the nerve root, the surgeon removes the injured disk tissue under it. The procedure does not change any of the structural supports of the spine, including joints, ligaments, and muscles.

Other, less invasive procedures are available, including endoscopic diskectomy, percutaneous diskectomy (PAD), and laser diskectomy. The long-term benefits of these procedures are unknown, however. There is no evidence that any of these less-invasive procedures are as effective as the standard microdiskectomy.

Complications and Outlook

Most people achieve pain relief and can move better after microdiskectomy. Numbness and tingling should get better or disappear. Your pain, numbness, or weakness may not get better or go away if the disk damaged your nerve before surgery.

Scar tissue is a potential problem, since it can cause persistent low back pain afterward. Other complications of spinal surgery can include nerve and muscle damage, infection, and the need for another operation.

People are usually up and walking soon after disk surgery. However, it may take 4 to 6 weeks for full recovery. Gentle exercise may be recommended at first. Starting intensive exercise 4 to 6 weeks after a first-time disk surgery appears to be very helpful for speeding up recovery. Little or no physical therapy is usually needed.

Laminectomy is surgery to remove either the lamina, 2 small bones that make up a vertebra, or bone spurs in your back. Laminectomy opens up your spinal canal so your spinal nerves or spinal cord have more room. It is often done along with a diskectomy, foraminotomy, and spinal fusion.

Laminectomy is frequently done to treat spinal stenosis. Spinal stenosis symptoms often become worse over time, but this may happen very slowly. Surgery may help when your symptoms become more severe and interfere with your daily life or job.

Laminectomy for spinal stenosis will often provide full or partial relief of symptoms for many people, but it is not always successful.

Future spine problems are possible for all people after spine surgery. If you had spinal fusion and laminectomy, the spinal column above and below the fusion are more likely to have problems in the future. If you needed more than one kind of back surgery (such as laminectomy and spinal fusion), you may have more of a chance of future problems.

Some recurrence of back pain and sciatica occurs in half to two-thirds of postoperative people. Minimally invasive variations are under investigation. For spinal stenosis, the traditional approach is a laminectomy and partial removal of the facet joint. There is controversy whether performing a fusion procedure along with these procedures is needed.

Spinal Fusion

Spinal fusion is surgery to fuse spine bones (vertebrae) that cause you to have back problems. Fusing means 2 bones are permanently placed together so there is no longer movement between them.

Spinal fusion is usually done along with other surgical procedures of the spine, such as a diskectomy, laminectomy, or a foraminotomy. It is done to prevent any movement in a certain area of the spine.

Conditions fusion may be done for include:

- Spinal stenosis

- Injury or fractures to the bones in the spine

- Surgery performed on 2 or more levels of the spine

- Weak or unstable spine

- Spondylolisthesis, a condition in which one vertebra slips forward on top of another

- Abnormal curvatures, such as those from scoliosis or kyphosis

The surgeon will use a graft (such as bone) to hold (or fuse) the bones together permanently. There are several different ways of fusing vertebrae together:

- Placing strips of bone graft material over the back part of the spine

- Placing bone graft material between the vertebrae

- Placing special cages between the vertebrae. These cages are packed with bone graft material.

The surgeon may get the graft from different places:

- From another part of your body (usually around your pelvic bone). This is called an autograft. Your surgeon will make a small cut over your hip and remove some bone from the back of the rim of the pelvis.

- From a bone bank, in a procedure called an allograft.

- A synthetic bone substitute can also be used.

The vertebrae are often also fixed together with screws, plates, rods, or cages. These are used to keep the vertebrae from moving until the bone grafts fully heal.

Future spine problems are possible for all people after spine surgery. After spinal fusion, the area that was fused together can no longer move. Therefore, the spinal column above and below the fusion is more likely to be stressed when the spine moves and develop problems later on. Also, if you needed more than one kind of back surgery (such as laminectomy and spinal fusion), you may have more of a chance of future back problems.

There are many video-assisted fusion techniques. These new techniques are less invasive than standard "open" surgical approaches, which use wide incisions. To date, however, the newer procedures have higher complication rates than the open approaches, and some medical centers have abandoned them.

Percutaneous Vertebroplasty

Percutaneous vertebroplasty involves the injection of a cement-like bone substitute into vertebrae with compression fractures. It is done under endoscopic and x-ray guidance.

Warning: The FDA has warned consumers that polymethylmethacrylate bone cement, used during vertebroplasty, could leak. Such leakage could cause damage to soft tissues and nerves. It is extremely important that the person is sure that the provider has had significant experience performing the vertebroplasty procedure. A major trial reported little benefit from vertebroplasty. More research is needed.

Percutaneous Kyphoplasty

The provider injects bone cement into the space surrounding a fractured vertebra. (Vertebroplasty injects the cement directly into the vertebra.) Kyphoplasty is used to stabilize the spine and return spinal height to as normal as possible. Kyphoplasty should only be done if bed rest, medicines, and physical therapy do not relieve back pain. Those with severe fractures or spinal infections should not have kyphoplasty. More research on kyphoplasty is needed.

Artificial Disk Replacement

Total disk replacement is a newer procedure for people with damaged disks. It may be done instead of spinal fusion surgery, such as for people who do not have severe spine disease above and below the site of surgery.

The technique implants artificial disks (such as ProDisc, Link, and SB Charite). The surgery can be performed through small cuts using miniature tools and viewing devices. The artificial cushioning device replaces only the inner gel-like core, rather than the entire disk.

After disk replacement surgery, there is preserved movement in the spine above and below the site of surgery than there is after fusion surgery. This extra movement may prevent further disk degeneration.

Disk replacement surgery has not yet been shown to be superior to traditional spine surgery and sufficient long-term outcomes are still lacking.

Intradiscal Electrothermal Treatment (IDET)

Intradiscal electrothermal treatment (IDET) uses electricity to heat a painful disk. Heat is applied for about 15 minutes. Pain may temporarily feel worse, but after healing, the disk shrinks and becomes desensitized to pain. However, healing takes several weeks. While some studies have reported benefit, many consider the evidence to support the use of this procedure weak.

Prognosis

Most people with acute low back pain are back at work within a month and fully recover within a few months. However, up to 75% of people suffer at least one recurrence of back pain over the course of a year. After 4 years, fewer than half of people may be symptom free. Some doctors are approaching the problem as one that is not necessarily curable and that needs a consistent on-going approach.

Resources

- National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases -- www.niams.nih.gov

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons -- www.aaos.org

- Arthritis Foundation -- www.arthritis.org

- American Physical Therapy Association -- www.apta.org

- American Pain Society -- americanpainsociety.org

- American Chronic Pain Association -- www.acpanow.com/

- International Association for the Study of Pain -- www.iasp-pain.org

References

Borondy-Kitts A. Patient-friendly summary of the ACR appropriateness criteria: low back pain. J Am Coll Radiol. 2018;S1546-1440(17)31165-1. PMID: 29519636 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29519636/.

Chou R, Qaseem A, Owens DK, Shekelle P; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Diagnostic imaging for low back pain: advice for high-value health care from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(3):181-189. PMID: 21282698 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21282698/.

Choi BK, Verbeek JH, Tam WW, Jiang JY. Exercises for prevention of recurrences of low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD006555. PMID: 20091596 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20091596/.

Cohen SP, Raja SN. Pain. In: Goldman L, Schafer AI, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 26th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2020:chap 27.

Corwell BN. Back pain. In: Walls RM, Hockberger RS, Gausche-Hill M, eds. Rosen's Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:chap 32.

Dixit R. Low back pain. In: Firestein GS, Budd RC, Gabriel SE, McInnes IB, O'Dell JR, eds. Kelley and Firestein's Textbook of Rheumatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017:chap 47.

Emch TM, Krishnaney AA, Modic MT. Radiology of the spine. In: Winn HR, ed. Youmans and Winn Neurological Surgery. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017:chap 12.

Gardocki RJ, Park AL. Degenerative disorders of the thoracic and lumbar spine. In: Azar FM, Beaty JH, Canale ST, eds. Campbell's Operative Orthopaedics. 13th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017:chap 39.

Geneen LJ, Moore RA, Clarke C, Martin D, Colvin LA, Smith BH. Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD011279. PMID: 28436583 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28436583/.

Grabowski G, Gilbert TM, Larson EP, Cornett CA. Degenerative conditions of the cervical and thoracolumbar spine. In: Miller MD, Thompson SR, eds. DeLee, Drez, & Miller's Orthopaedic Sports Medicine. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2020:chap 130.

Long DM. Surgery for back and neck pain (including radiculopathies). In: McMahon SB, Koltzenburg M, Tracey I, Turk DC, eds. Wall & Melzack's Textbook of Pain. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2013:chap 71.

Maher C, Underwood M, Buchbinder R. Non-specific low back pain. Lancet. 2017;389(10070):736-747. PMID: 27745712 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27745712/.

Mahoney BD. Back pain. In: Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, eds. Rosen's Emergency Medicine Concepts and Clinical Practice. 8th ed. Phialdelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:chap 35.

Malik K, Benzon HT. Low back pain. In: Benzon HT, Rathmell JP, Wu CL, Turk DC, Argoff CE, Hurley RW, eds. Practical Management of Pain. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Mosby; 2014:chap 21.

Mazur MD, Shah LM, Schmidt MH. Assessment of spinal imaging. In: Winn HR, ed. Youmans and Winn Neurological Surgery. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017:chap 274.

Oliveira CB, Maher CG, Pinto RZ, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care: an updated overview. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(11):2791-2803. PMID: 29971708 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29971708/.

Patel ND, Broderick DF, Burns J, et al. ACR appropriateness criteria low back pain. J Am Coll Radiol. 2016;13(9):1069-1078. PMID: 27496288 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27496288/.

Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(7):514-530. PMID: 28192789 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28192789/.

Samad A, Usmani MF, Khanna AJ. Imaging of the spine. In: Miller MD, Thompson SR, eds. DeLee, Drez, & Miller's Orthopaedic Sports Medicine. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2020:chap 12.

Sudhir A, Perina D. Musculoskeletal back pain. In: Walls RM, Hockberger RS, Gausche-Hill M, eds. Rosen's Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:chap 47.

van der Gaag WH, Roelofs PD, Enthoven WT, van Tulder MW, Koes BW. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for acute low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;4(4):CD013581. PMID: 32297973 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32297973/.

Van Tulder M, Koes B. Low back pain. In: McMahon SB, Koltzenburg M, Tracey I, Turk DC, eds. Wall & Melzack's Textbook of Pain. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2013:chap 49.

Vlaeyen JWS, Maher CG, Wiech K, et al. Low back pain. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4(1):52. Published 2018 Dec 13. PMID: 30546064 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30546064/.

Reviewed By: C. Benjamin Ma, MD, Professor, Chief, Sports Medicine and Shoulder Service, UCSF Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, San Francisco, CA. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.