Herpes simplex - InDepth

Highlights

- Herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) is the main cause of oral herpes infections that occur on the mouth and lips. These include cold sores and fever blisters. HSV-1 can also cause genital herpes.

- Herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2) is the most common cause of genital herpes, but it can also cause oral herpes.

Genital herpes can be caused by either HSV-2 or HSV-1. In the past, most genital herpes cases were caused by HSV-2. In recent years, HSV-1 has become a significant cause in developed countries, including the United States. Oral sex with an infected partner can transmit HSV-1 to the genital area.

Genital herpes is a sexually transmitted disease (STD) spread by skin-to-skin contact. The risk of infection is highest during outbreak periods when there are visible sores and lesions. However, genital herpes can also be transmitted when there are no visible symptoms. Most new cases of genital herpes infection do not cause symptoms, and many people infected with HSV-2 are unaware that they have genital herpes.

To help prevent genital herpes transmission:

- Use a condom for sexual intercourse.

- Use a dental dam for oral sex.

- Limit your number of sexual partners.

- Be aware that nonoxynol-9, the chemical spermicide used in gel and foam contraceptive products and some lubricated condoms, does not protect against STDs.

When genital herpes symptoms do appear, they are usually worse during the first outbreak than during recurring attacks. During an initial outbreak:

- Symptoms usually appear within 1 to 2 weeks after sexual exposure to the virus.

- The first signs are a tingling sensation in the affected areas (genitalia, buttocks, and thighs), and groups of small red bumps that develop into blisters.

- Over the next 2 to 3 weeks, more blisters can appear and rupture into painful open sores.

- The lesions eventually dry out and develop a crust, and then usually heal rapidly without leaving a scar.

- Flu-like symptoms are common during initial outbreaks of genital herpes. They include headache, muscle aches, fever, and swollen glands.

- Rarely, lesions may develop in the area of the urethra (the opening from the bladder). If that happens, the patient may need to have a catheter inserted as the pain from the lesions makes urination difficult or impossible.

Herpes can pose serious risks for a pregnant woman and her baby. The risk is greatest for mothers with a first-time infection because the virus can be transmitted to the infant during childbirth. Guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics recommend using specific diagnostic tests for women in labor to determine the risk of transmission. Babies born to mothers infected with genital herpes are often treated with the antiviral drug acyclovir, which can help suppress the virus.

Introduction

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is a common virus that causes infections of the skin and mucous membranes. It can sometimes cause more serious infections in other parts of the body.

HSV is part of a group of 8 viruses in the Herpes virus family that can cause human disease. Other viruses in this group include the varicella-zoster virus (VZV, also known as herpes zoster, the virus responsible for shingles and chickenpox), the cytomegalovirus (CMV), and the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). There are many other strains of herpes viruses that can infect various animals.

Herpes viruses differ in many ways, but the viruses share certain characteristics. The word "herpes" comes from the Greek word "herpein," meaning "to creep." This refers to the unique characteristic pattern of all herpes viruses to creep along local nerve pathways to the nerve clusters at the end, where they remain in an inactive (dormant) state for variable periods of time. This period of inactivity is called latency.

There are two forms of HSV:

- Herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1). The usual cause of oral herpes (herpes labialis), which are commonly called cold sores or fever blisters. HSV-1 can also cause genital herpes, which is a sexually transmitted disease (STD).

- Herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2). The usual cause of genital herpes, but it can also cause oral herpes.

HSV-1 and HSV-2 are distinguished by different proteins on their surfaces. They can infect separately, or they can both infect the same individual. Until recently, the general rule was to assume that HSV-1 caused oral herpes and HSV-2 caused genital herpes. It is now clear, however, that either type of herpes virus can be found in the genital or oral areas (or other sites). In fact, HSV-1 is now responsible for more than half of all new cases of genital herpes in developed countries.

Herpes is transmitted through close skin-to-skin contact. To infect people, the herpes simplex viruses (both HSV-1 and HSV-2) must get into the body through tiny injuries in the skin or through a mucous membrane, such as inside the mouth or on the genital or anal areas. The risk for infection is highest with direct contact of blisters or sores during an outbreak. But the infection can also develop from contact with an infected partner who does not have visible sores or other symptoms.

Once the virus has contact with the mucous membranes or skin wounds, it enters the nuclei of skin tissue cells and begins to replicate. The virus is then transported from the nerve endings of the skin to clusters of nerve cells (ganglia) where it remains inactive (latent) for some period of time.

During inactive periods, the virus is in a sleeping (dormant) state and cannot be transmitted to another person. However, at some point, the virus wakes up and travels along nerve pathways to the surface of the skin where it begins to multiply again. During this time, the virus can infect other people if it is passed along in body fluids or secretions.

This period of reactivation, replication, and transmission is called viral shedding. Viral shedding may be accompanied by noticeable symptoms (outbreak) but it can also occur without causing symptoms (asymptomatic shedding). In either case, a person is infectious during periods of viral shedding.

Symptoms may appear as multiple small red bumps or patches that develop blisters. The first time that herpes symptoms occur is called a primary, or initial, outbreak. Subsequent outbreaks are called recurrences. No one can predict when a herpes outbreak will recur. Certain triggers can wake up the virus from its dormant state and cause it to become active again. These triggers include things like stress, illness, and sunlight. In general, recurrent episodes of herpes cause less severe symptoms than the primary outbreak.

Once a person becomes infected with herpes simplex, the virus remains in the body for a very long time. Outbreaks tend to lessen over time.

This close-up view of an early herpes outbreak shows small, grouped blisters (vesicles) and lots of inflammation (erythema).

Transmission of Oral Herpes

Oral herpes is usually caused by HSV-1. HSV-1 is the most prevalent form of HSV, and infection rates increase with age, so that most adults over 40 years old are seropositive for HSV-1. Oral herpes is easily spread by oral to oral contact. Transmission most often occurs through close personal contact, such as kissing, but can also occur by sharing objects that have contact with saliva.

Transmission of Genital Herpes

Genital herpes is transmitted through sexual activity. People can get HSV-2 through genital contact or HSV-1 through mouth-to-genital contact with an infected partner.

People with multiple sexual partners are at high risk as are those who do not use condoms. People with active symptoms of genital herpes are at very high risk for transmitting the infection. Unfortunately, most cases of genital herpes infections occur when the virus is shedding but producing no symptoms. Most people either have no symptoms or do not recognize them when they appear.

In the past, genital herpes was mostly caused by HSV-2, but HSV-1 genital infection is increasing. This may be due to the increase in oral sex activity among young adults. There is also evidence that children today are less likely to get cold sores and become exposed to HSV-1 during childhood. If adolescents do not have antibodies to HSV-1 by the time they become sexually active, they may be more susceptible to genitally acquiring HSV-1 through oral sex.

Risk Factors

Oral herpes is usually caused by HSV-1. The first infection usually occurs between 6 months and 3 years of age. According to CDC estimates from 2015-2016, the prevalence of HSV-1 was 47.8% in the adult population (ages 14 to 49 years).

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), about 1 in 6 Americans ages 14 to 49 years have genital herpes. While HSV-2 remains the main cause of genital herpes, HSV-1 has significantly increased as a cause, most likely because of oral-genital sex. Except for people in monogamous relationships with uninfected partners, everyone who is sexually active is at risk for genital herpes.

Risk factors for genital herpes include:

- History of an STD

- First sexual intercourse at an early age

- High number of sexual partners

- Low socioeconomic status

Women are more susceptible to HSV-2 infection because herpes is more easily transmitted from men to women than from women to men. About 1 in 5 women, compared to 1 in 9 men, have genital herpes. African-American women are at particularly high risk.

People with compromised immune systems, such as those who have HIV, are at very high risk for genital herpes. These people are also at risk for more severe complications from herpes. Drugs that suppress the immune system, and organ transplantation, can also weaken the immune system and increase the risk for contracting genital herpes.

The only definite way to prevent genital herpes is to abstain from sex or to engage in sex in a mutually monogamous relationship with an uninfected partner.

Infected people should take steps to avoid transmitting genital herpes to others. It is almost impossible to defend against the transmission of oral herpes, because it can be transmitted by very casual contact, including kissing. Still, you can help reduce the risk of transmitting oral herpes by not sharing objects that touch the mouth, such as eating and drinking utensils, toothbrushes, and towels.

Genital herpes is contagious from the first signs of tingling and burning (prodrome) until sores have completely healed. It is best to refrain from any type of sex (vaginal, anal, or oral) during periods of active outbreak. However, herpes can also be transmitted when symptoms are not present (asymptomatic shedding).

The following precautions can help reduce the risk of transmission:

- Use a condom. Although condoms may not provide 100% protection, they are proven to significantly reduce the risk of sexual disease transmission, including herpes. Condoms made of latex are less likely to slip or break than those made of polyurethane. Natural condoms made from animal skin do NOT protect against HSV infection because herpes viruses can pass through them.

- Use a water-based lubricant. Lubricants can help prevent friction during sex, which can irritate the skin and increase the risk for outbreaks. Only water-based lubricants (K-Y Jelly, Astroglide, AquaLube, and glycerin) should be used. Oil-based lubricants (petroleum jelly, body lotions, and cooking oil) can weaken latex. Many condoms come pre-lubricated. However, it is best not to use condoms pre-lubricated with spermicides.

- Do not use spermicides for protection against herpes. Some condoms come pre-lubricated with sperm-killing substances called spermicides. Spermicides also come in standalone foams and jellies. The standard active ingredient in spermicides is nonoxynol-9. Nonoxynol-9 can cause irritation around the genital areas, which makes it easier for herpes and other STDs to be transmitted.

- Use a dental dam or condom for oral sex. Dental dams are small square pieces of latex that can be used as a barrier for oral sex. You can also use a latex condom or make a dental dam by cutting a condom. If you have any symptoms of oral herpes, it is best not to perform oral sex on a partner until any visible sores or blisters have healed.

- Limit the number of sexual partners. The more sexual partners you have, the greater your chances of becoming infected or infecting others.

The herpes virus does not live very long outside the body. It is very unlikely to transmit or contract genital herpes from a toilet seat or bath towel.

Studies suggest that male circumcision may help reduce the risk of HSV-2, as well as human papillomavirus (HPV) and HIV infections. However, circumcision does not prevent STDs. Men who are circumcised should still practice safe sex, including using condoms.

There is currently no vaccine to prevent genital herpes, but several investigational herpes vaccines are being studied in clinical trials.

Complications

Except in very rare instances and special circumstances, HSV is not life threatening. However, herpes can cause significant and widespread complications in people who don't have a fully functioning immune system.

People infected with herpes have an increased risk for acquiring and transmitting HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. The CDC recommends that all people diagnosed with HSV-2 get tested for HIV.

People with HIV who are co-infected with HSV-2 are particularly vulnerable to its complications. When a person has both viruses, each virus increases the severity of the other. HSV-2 infection increases HIV levels in the genital tract, which makes it easier for the HIV virus to be spread to sexual partners.

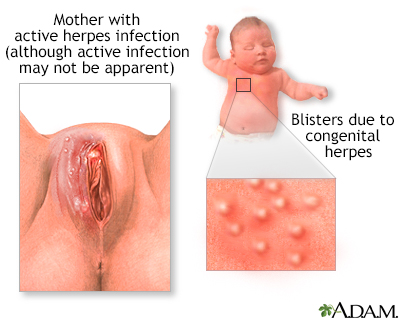

Pregnant women who have genital herpes due to either HSV-2 or HSV-1 carry a risk of transmission of the herpes infection to the infant in the uterus or at the time of delivery. Herpes in newborn babies (herpes neonatalis) can be a very serious condition.

Fortunately, neonatal herpes is rare. Although about 25% to 30% of pregnant women have genital herpes, less than 0.1% of babies are born with neonatal herpes. The baby is at greatest risk during a vaginal delivery, especially if the mother has an asymptomatic infection that was first introduced late in the pregnancy. In such cases, 30% to 50% of newborns become infected. This is because:

- During a first (primary) infection, the virus is shed for longer periods.

- An infection that first occurs in the late term of pregnancy does not allow enough time for the mother to develop antibodies that would help her baby fight off the infection at the time of delivery.

- Recurring herpes, or a first infection that was acquired early in the pregnancy, pose a much lower risk to the infant.

The risk for transmission also increases if infants with infected mothers are born prematurely, there is invasive monitoring, or instruments are used during vaginal delivery. Transmission can occur if the amniotic membrane of an infected woman ruptures prematurely, or as the infant passes through an infected birth canal. This risk is increased if the woman is having or has recently had an active herpes outbreak in the genital area.

Very rarely, the virus is transmitted across the placenta, a form of the infection known as congenital herpes. Also rarely, newborns may contract herpes during the first weeks of life from being kissed by someone with a herpes cold sore.

Infants may get congenital herpes from a mother with an active herpes infection at the time of birth. Aggressive treatment with antiviral medication is required.

Most infected pregnant women do not have a history of symptoms, so herpes infection is often not suspected or detected at the time of delivery.

- The American College of Obstetricians & Gynecologists recommends that Cesarean delivery should be performed on women with recurrent HSV infection who have active genital lesions or prodromal symptoms at delivery.

- Expectant management of patients with preterm labor or preterm premature rupture of membranes and active HSV infection may be warranted.

- For women at or beyond 36 weeks of gestation who are at risk for recurrent HSV infection, antiviral therapy also may be considered, although such therapy may not reduce the likelihood of cesarean delivery.

- In women with no active lesions or prodromal symptoms during labor, cesarean delivery should not be performed on the basis of a history of recurrent disease.

If you are pregnant and have a history of HSV, it is very important that you notify your health care provider of that history. You should notify them even if you're not sure of the diagnosis.

Herpes infection in a newborn can cause a range of symptoms, including skin rash, fevers, mouth sores, and eye infections. If left untreated, neonatal herpes is a very serious and even life-threatening condition. Neonatal herpes can spread to the brain and central nervous system, causing encephalitis and meningitis. It also can lead to intellectual disability, cerebral palsy, and death. Herpes can also spread to internal organs, such as the liver and lungs.

Infants infected with herpes are treated with acyclovir, an antiviral drug. They usually receive several weeks of intravenous acyclovir treatment, often followed by several months of oral acyclovir. It is important to treat babies quickly, before the infection spreads to the brain and other organs.

Herpes Encephalitis

Herpes simplex encephalitis is inflammation of the brain caused by either HSV-1 or HSV-2. It is a rare but extremely serious brain disease. Untreated, herpes encephalitis is fatal most of the time. Respiratory arrest can occur within the first 24 to 72 hours. Fortunately, rapid diagnostic tests and treatment with acyclovir have significantly improved survival rates and reduced complication rates. Nearly all who recover have some impairment, ranging from very mild neurological changes to paralysis.

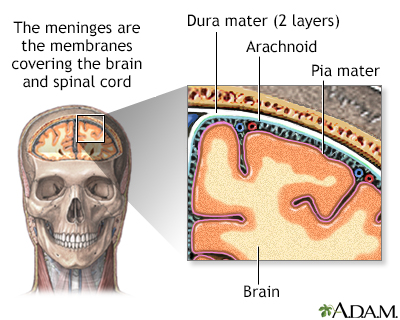

Herpes Meningitis

Herpes simplex meningitis is inflammation of the membranes that line the brain and spinal cord. It is mainly caused by HSV-2. Like encephalitis, meningitis symptoms include headache, fever, stiff neck, vomiting, and sensitivity to light. Fortunately, herpes meningitis usually resolves after about a week without complications, although symptoms can recur.

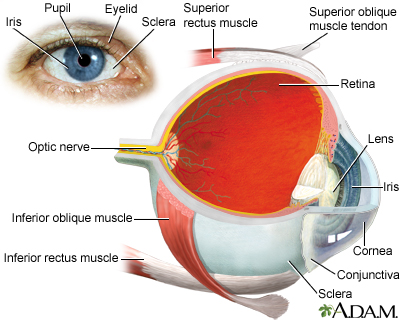

Ocular herpes is a recurrent infection that affects the eyes. It is mainly caused by HSV-1, but can also be caused by HSV-2. Ocular herpes is usually a simple infection that clears up in a few days, but in its more serious forms, and in severe cases, it can cause blindness. As a result, medical attention should be sought immediately for any suspicion of herpes infections around or in the eyes.

Types of ocular herpes include:

- Superficial Keratitis. This condition involves infection and inflammation of the cornea. It is the most common form of ocular herpes. It only affects the upper layer (epithelium) of the cornea and heals with scarring.

- Stromal Keratitis. This condition involves deeper layers of the cornea. Corneal scarring develops, which may result in blindness. Although rare, it is a leading cause of blindness in the US.

- Iridocyclitis. Iridocyclitis is another serious complication of ocular herpes, in which the iris and the area around it become inflamed. Iridocyclitis is related to the eye condition uveitis. It can cause increased sensitivity to light. If left untreated, it can result in vision loss.

Eczema Herpeticum

A rare form of herpes infection called eczema herpeticum, also known as Kaposi varicelliform eruption, can affect people with atopic dermatitis and other skin disorders and those with a weakened immune system. The disease tends to develop into a widespread skin infection that resembles impetigo. Symptoms appear abruptly and can include fever, chills, and malaise. Clusters of dimpled blisters emerge over 7 to 10 days and spread widely. They can become secondarily infected with staphylococcal or streptococcal bacteria. With treatment, lesions heal in 2 to 6 weeks. Untreated, this condition can be extremely serious and possibly fatal.

Gingivostomatitis

Oral herpes can cause multiple painful ulcers on the gums and mucous membranes of the mouth, a condition called gingivostomatitis. This condition usually affects children ages 1 to 5 years. It often subsides within 2 weeks. Children with gingivostomatitis commonly develop herpetic whitlow (herpes of the fingers).

Herpetic Whitlow

A herpetic whitlow is an infection of the herpes virus involving the finger, often around the fingernail. In children, this is often caused by thumb sucking or finger sucking while they have a cold sore. It can also occur in adult health care workers, such as dentists, because of increased exposure to the herpes virus. The use of latex or polyurethane gloves prevents herpes whitlow in health care workers.

Symptoms

Herpes symptoms vary depending on whether the outbreak is initial or recurrent. The primary outbreak is usually worse than recurrent outbreaks, with more severe and prolonged symptoms. However, most cases of herpes simplex virus infections do not produce symptoms. In fact, studies indicate that 10% to 25% of people infected with HSV-2 are unaware that they have genital herpes. Even if infected people have mild or no symptoms (asymptomatic), they can still transmit the herpes virus.

Primary Genital Herpes Outbreak

For people with symptoms, the first outbreak usually occurs in or around the genital area 2 days to 2 weeks after sexual exposure to the virus. The first signs are a tingling sensation in the affected areas (genitalia, buttocks, and thighs) and groups of small red bumps that develop into blisters. Over the next 2 to 3 weeks, more blisters can appear and rupture into painful open sores. The lesions eventually dry out, develop a crust, and heal rapidly without leaving a scar. Blisters in moist areas heal more slowly than those in dry areas. The sores may sometimes itch, but itching decreases as they heal.

About 40% of men and 70% of women develop other symptoms during initial outbreaks of genital herpes, such as flu-like discomfort, headache, muscle aches, and fever. Swollen glands may occur in the groin area or neck. Some women may have difficulty urinating and may, occasionally, require a urinary catheter. Women may also experience vaginal discharge.

Recurrent Genital Herpes Outbreak

In general, recurrences are much milder than the initial outbreak. The virus sheds for a much shorter period of time (about 3 days) compared to an initial outbreak of 3 weeks. Women may have only minor itching, and the symptoms may be even milder in men.

On average, people have about 4 recurrences during the first year, although this varies widely. Over time, recurrences decrease in frequency. There are some differences in frequency of recurrence depending on whether HSV-2 or HSV-1 caused genital herpes. HSV-2 genital infection is more likely to cause recurrences than HSV-1.

Oral herpes (herpes labialis) is most often caused by HSV-1, but can also be caused by HSV-2. It usually affects the lips and, in some primary attacks, the mucous membranes in the mouth. A herpes infection may occur on the cheeks or in the nose, but facial herpes is very uncommon.

Primary Oral Herpes Infection

If the primary (initial) oral infection causes symptoms, they can be very painful, particularly in children. Symptoms include:

- Tingling, burning, or itching around the mouth are the first signs.

- Red, fluid-filled blisters that may form on the lips, gums, mouth, and throat.

- Blisters that break open and leak. As they heal, they turn yellow and crusty, eventually turning into pink skin. The sores last 10 to 14 days and can be very uncomfortable.

- Blisters that may be preceded or accompanied by sore throat, fever, swollen glands, and painful swallowing.

Recurrent Oral Herpes Infection

A recurrent oral herpes infection is much milder than the primary outbreak. It usually manifests as a single sore, commonly called a cold sore or fever blister (because it may arise during a bout of cold or flu). The sore usually shows up on the outer edge of the lips and rarely affects the gums or throat. (Cold sores are commonly mistaken for the crater-like mouth lesions known as canker sores, which are not associated with HSV.)

Course of Recurrence

Most cases of herpes simplex recur. The site on the body and the type of virus influence how often it comes back. Recurrences of genital herpes are more likely with HSV-2 infection than with HSV-1 infection.

The virus usually takes the following course:

- Prodrome. The outbreak of infection is often preceded by a prodrome, an early group of symptoms that may include itchy skin, pain, or an abnormal tingling sensation at the site of infection. Headache, enlarged lymph glands, and flu-like symptoms may occur. The prodrome, which may last from 2 hours to 2 days, stops when the blisters develop. About 25% of the time, recurrence does not go beyond the prodrome stage.

- Outbreak. Recurrent outbreaks feature most of the same symptoms at the same sites as the primary attack, but they tend to be milder and briefer. After blisters erupt, they typically heal in 6 to 10 days. Occasionally, the symptoms may not resemble those of the primary episode, but appear as fissures and scrapes in the skin or as general inflammation around the affected area.

Triggers of Recurrence

Herpes outbreaks can be triggered by different factors. They include sunlight, wind, fever, physical injury, surgery, menstruation, suppression of the immune system, and emotional stress. Oral herpes can be triggered within about 3 days of intense dental work, particularly root canal or tooth extraction.

Timing of Recurrences

Recurrent outbreaks may occur at intervals of days, weeks, or years. For most people, outbreaks recur with more frequency during the first year after an initial attack. During that period, the body mounts an intense immune response to HSV. The good news is that in most healthy people, recurring infections tend to become progressively less frequent, and less severe, over time. However, the immune system cannot kill the virus completely. HSV is a lifelong infection.

Diagnosis

The HSV is usually identifiable by its characteristic lesion: a thin-walled blister on an inflamed base of skin. However, other conditions can resemble herpes, and doctors cannot base a herpes diagnosis on visual inspection alone.

Many people who carry the virus do not have visible genital or oral lesions. Laboratory tests are needed to confirm a herpes diagnosis. These tests include:

- Virologic tests (tests that detect the virus itself)

- Serologic tests (blood tests that detect antibodies)

The CDC recommends that both virologic and serologic tests be used for diagnosing genital herpes. People diagnosed with genital herpes should also be tested for other STDs. At this time, experts do not recommend screening for HSV-1 or HSV-2 in the general population.

Genital herpes can be caused by either HSV-1 or HSV-2. It is important to determine which virus is involved, as the type of herpes infection influences prognosis and treatment recommendations. Recurrences of genital herpes, and viral shedding without overt symptoms, are much less frequent with HSV-1 infection than with HSV-2.

False-negative (testing negative when herpes infection is actually present) or false-positive (testing positive when herpes infection is not actually present) results can occur. Your provider may recommend that you have a test repeated.

Viral tests are made by taking a fluid sample, or culture, from the lesions as early as possible, ideally within the first 48 hours of the outbreak. As the lesion begins to heal, the test becomes less accurate. These tests can be used to distinguish between HSV-1 and HSV-2.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests analyze the genetic material (DNA) of the HSV and are helpful for differentiating HSV-1 from HSV-2. PCR tests are much faster and more accurate than viral cultures, and the CDC recommends PCR for detecting herpes in spinal fluid when diagnosing herpes encephalitis. PCR can make many copies of the virus' DNA, so that even small amounts of DNA in the sample can be detected. Because PCR is more sensitive and faster than viral cultures and many labs now use PCR for herpes testing.

An older type of virologic testing, the Tzanck smear test, uses scrapings from herpes lesions. The scrapings are stained and examined under a microscope for the presence of giant cells with many nuclei or distinctive particles that carry the virus (called inclusion bodies). The test is quick but accurate only 50% to 70% of the time. It cannot distinguish between HSV virus types or between herpes simplex and the varicella zoster virus. The Tzanck test is not reliable for providing a conclusive diagnosis of herpes infection and is not recommended by the CDC.

Serologic (blood) tests can identify antibodies that are specific for either HSV-1 or HSV-2. When the herpes virus infects you, your body's immune system produces specific antibodies to fight off the infection. If a blood test detects antibodies to herpes, it is evidence that you have been infected with the virus, even if the virus is in a non-active (dormant) state. The presence of antibodies to herpes also indicates that you are a carrier of the virus and might transmit it to others.

Serologic tests can be useful for people who do not have active symptoms, but who have other risk factors for herpes (such as other STDs, multiple sex partners, or a monogamous partner who has genital herpes).

Newer type-specific assays check for antibodies to two different proteins that are associated with the herpes virus:

- Glycoprotein gG-1 is associated with HSV-1.

- Glycoprotein gG-2 is associated with HSV-2.

Although glycoprotein (gG) type-specific tests have been available for many years, many of the older nontype-specific tests that cannot distinguish HSV-1 from HSV-2 are still on the market. The CDC recommends only type-specific glycoprotein (gG) tests for herpes diagnosis.

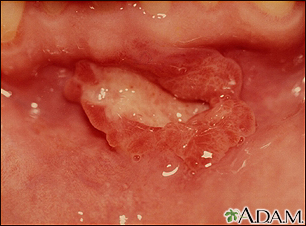

Canker Sores (Aphthous Ulcers)

Simple canker sores (known medically as aphthous ulcers) are often confused with the cold sores of HSV-1. Canker sores frequently crop up singly or in groups on the inside of the mouth, or on or underneath the tongue. Their cause is unknown, and they are common in perfectly healthy people. They are usually white or grayish crater-like ulcers with a sharp edge and a red rim. They usually heal within 2 weeks without treatment.

This aphthous ulcer is located in front of and just below the bottom teeth.

Thrush (Candidiasis)

Oral candidiasis is a yeast infection that causes a whitish overgrowth in the mouth. It is most common in infants, but can appear in people of all ages, particularly people taking antibiotics or those with impaired immune systems.

Other conditions that may be confused with oral herpes include herpangina (mouth lesions caused by Coxsackie A virus), sore throat caused by strep or other bacteria, and infectious mononucleosis.

Conditions that may be confused with genital herpes include bacterial, yeast and viral infections, which include granuloma inguinale, candidiasis, syphilis, chancroid, herpes zoster (shingles and chickenpox), and hand-foot-and-mouth disease.

Treatment for Genital Herpes

Three drugs are approved to treat genital herpes:

- Acyclovir (Zovirax, generic)

- Valacyclovir (Valtrex, generic)

- Famciclovir (Famvir, generic)

These medications are antiviral drugs called nucleoside analogues. The drugs are used initially to treat a first attack of herpes, and then afterward to either treat recurrent outbreaks (episodic therapy) or reduce frequency of recurrences (suppressive therapy).

No drug can cure herpes simplex virus. The infection may recur after treatment has been stopped. Even during therapy, an infected person can still transmit the virus to another person. Drugs can, however, reduce the severity of symptoms, improve healing times, and prevent recurrences.

Antiviral drugs for genital herpes are generally given as pills that are taken by mouth. If people experience very severe disease or complications, they need to be hospitalized and receive an antiviral drug intravenously. Acyclovir (Zovirax) is also available as an ointment, which can be used as an adjunct for treatment of initial genital herpes.

The first outbreak of genital herpes is usually much worse than recurrent outbreaks. Symptoms tend to be more severe and to last longer. Your provider will prescribe one of the three antiviral medications, which you will take for 7 to 10 days. If your symptoms persist, treatment may be extended. An acyclovir ointment may also be prescribed for topical treatment of initial genital herpes.

For a recurrent episode, treatment takes 1 to 5 days, depending on the type of medication and dosage. You should begin the medication as soon as you notice any signs or symptoms of herpes, preferably during the prodrome stage that precedes the outbreak of lesions.

In order for episodic therapy to be effective, it must be taken no later than 1 day after a lesion appears. If taken during prodrome, episodic therapy may help prevent an outbreak from occurring or reduce its severity. If taken at the first sign of a lesion, it can help speed healing.

To suppress outbreaks, treatment requires taking pills daily on a long-term basis. Acyclovir and famciclovir are taken twice a day for suppression. Valacyclovir is taken once a day. The doses for these antiviral drugs are reduced in people with impaired renal function.

Suppressive treatment can reduce the frequency of outbreak recurrences by 70% to 80%. It is generally recommended for people who have frequent recurrences (6 or more outbreaks per year). Because herpes recurrences often diminish over time, you should discuss annually with your provider whether you should stay with drug therapy or discontinue it.

There is some evidence that valacyclovir may help prevent herpes transmission, particularly in situations where one heterosexual partner has HSV-2 and the other partner does not. However, this drug does not completely prevent transmission. While taking any suppressive therapy for genital herpes, it is still important to regularly use latex condoms and to avoid any sexual activity during recurrences.

Antiviral drugs are generally safe. The most common side effects are nausea, headache, and abdominal pain.

Treatment for Oral Herpes

Acyclovir (Zovirax, generic), valacyclovir (Valtrex), and famciclovir (Famvir), the antiviral pills used to treat genital herpes, can also treat the cold sores associated with oral herpes (herpes labialis). A new form of acyclovir (Sitavig) is administered orally as an adhesive tablet; it is applied to the gum region of the mouth, where it dissolves during the course of the day. In addition, acyclovir is available in topical form, as is the related drug penciclovir (Denavir).

These ointments or creams can help shorten healing time and duration of symptoms. However, none are truly effective at eliminating outbreaks.

- Penciclovir (Denavir) heals HSV-1 sores on average about half a day faster than without treatment, stops viral shedding, and reduces the duration of pain. Ideally, you should apply the cream within the first hour of symptoms, although the medication can still help if applied later. The drug is continued for 4 consecutive days, and should be reapplied every 2 hours while awake.

- Acyclovir cream (Zovirax, generic) works best when applied early (at the first sign of pain or tingling).

- Docosanol cream (Abreva) is the only FDA-approved nonprescription ointment for oral herpes. Apply the cream 5 times a day, beginning at the first sign of tingling or pain.

- Over-the-counter topical ointments may provide modest relief. They include Anbesol gel, Blistex lip ointment, Campho-phenique, Herpecin-L, Viractin, and Zilactin. Some contain a topical anesthetic such as benzocaine, tetracaine, or phenol.

- Lip balm that contains sunblock, or sunscreen applied around the lips may help prevent sun-triggered outbreaks.

Home Remedies

Most herpes simplex infections that develop on the skin can be managed at home with over-the-counter painkillers and simple measures to relieve symptoms.

To ease symptoms:

- Take acetaminophen, ibuprofen, or aspirin to relieve pain.

- Apply cool or warm compresses to sores several times a day to relieve pain and itching.

- Women with sores on the vaginal lips (labia) can try urinating in a tub of water to avoid pain.

- For oral herpes, rinse your mouth with cool water and gargle with salt water. Avoid spicy and salty foods, citrus fruits, and hot water.

Doing the following can help sores heal:

- Wash sores gently with soap and water. Then pat dry.

- Do not bandage sores. Air speeds healing.

- Do not pick at sores. They can get infected, which slows healing.

- Do not use ointment or lotion on sores unless your provider prescribes it.

- For genital herpes, wear loose-fitting cotton underwear. Do not wear nylon or other synthetic pantyhose or underwear. Also do not wear tight-fitting pants.

Generally, manufacturers of herbal remedies and dietary supplements do not need FDA approval to sell their products. Just like a drug, herbs and supplements can affect the body's chemistry, and therefore have the potential to produce side effects that may be harmful. There have been several reported cases of serious and even lethal side effects from herbal products. Always check with your provider before using any herbal remedies or dietary supplements.

The following are special concerns for people taking natural remedies for herpes simplex:

- Echinacea can lower white blood cell levels when taken for long periods of time. This herb can also interfere with drugs that are used to treat immune system disorders.

- Siberian ginseng can raise blood pressure levels.

- Bee products (like propolis) can cause allergic reactions in people who are allergic to bee stings.

- Lysine should not be taken with certain types of antibiotics.

- Taking zinc in large amounts (more than 200 mg/day) can cause stomach upset and an impaired sense of smell.

Resources

- American Sexual Health Association -- www.ashasexualhealth.org

- National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases -- www.niaid.nih.gov

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention -- www.cdc.gov/std/herpes

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecology -- www.acog.org

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr6403.pdf. Updated June 5, 2015. Accessed November 28, 2023.

Chi CC, Wang SH, Delamere FM, Wojnarowska F, Peters MC, Kanjirath PP. Interventions for prevention of herpes simplex labialis (cold sores on the lips). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;8:CD010095. PMID: 26252373 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26252373/.

Downing C, Mendoza N, Sra K, Tyring SK. Human herpesviruses. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:chap 80.

Dinulos JGH. Warts, herpes simplex, and other viral infections. In: Dinulos JGH, ed. Habif’s Clinical Dermatology. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 12.

Kimberlin DW, Baley J; Committee on infectious diseases; Committee on fetus and newborn. Guidance on management of asymptomatic neonates born to women with active genital herpes lesions. Pediatrics. 2013;131(2):e635-e6346. PMID: 23359576 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23359576/.

Mazur LJ, Costello M. Viral infections. In: McPherson RA, Pincus MR, eds. Henry's Clinical Diagnosis and Management by Laboratory Methods. 23rd ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2017:chap 56.

Mathew Jr J, Sapra A. Herpes Simplex Type 2. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; August 10, 2020. PMID: 32119314 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32119314/.

McQuillan G, Kruszon-Moran D, Flagg EW, Paulose-Ram R. Prevalence of herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 in persons aged 14-49: United States, 2015-2016. NCHS Data Brief. 2018;(304):1-8. PMID: 29442994 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29442994/.

Patton ME, Bernstein K, Liu G, Zaidi A, Markowitz LE. Seroprevalence of Herpes Simplex Virus Types 1 and 2 Among Pregnant Women and Sexually Active, Nonpregnant Women in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67(10):1535-1542. PMID: 29668856 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29668856/.

Saleh D, Sharma S. Herpes Simplex Type 1. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; August 13, 2020. PMID: 29489260 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29489260/.

Schiffer JT, Corey L. Herpes simplex virus. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 135.

Stanberry LR. Herpes simplex virus. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 279.

Sterling JC. Herpes labialis. In: Lebwohl MG, Heymann WR, Berth-Jones J, Coulson IH, eds. Treatment of Skin Disease: Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:chap 104.

Sychev YV, Kumar Rao P. Herpetic viral uveitis. In: Yanoff M, Duker JS, eds. Ophthalmology. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019:chap 7.4.

US Preventive Services Task Force, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al. Serologic screening for genital herpes infection: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;316(23):2525-2530. PMID: 27997659 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27997659/.

Vangipuram R, Karas L, Sharghi K, Peranteau J, Tyring SK. Herpes genitalis. In: Lebwohl MG, Heymann WR, Berth-Jones J, Coulson IH, eds. Treatment of Skin Disease: Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:chap 103.

Whitley RJ, Gnann JW. Herpes simplex virus infections. In: Goldman L, Schafer AI, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 26th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2020:chap 350.

Reviewed By: John D. Jacobson, MD, Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Loma Linda University School of Medicine, Loma Linda Center for Fertility, Loma Linda, CA. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.