Rheumatoid arthritis - InDepth

Highlights

RA is a chronic autoimmune disease in which the body's immune system attacks joints and other tissues. RA can also cause complications in other areas of the body, including the organs.

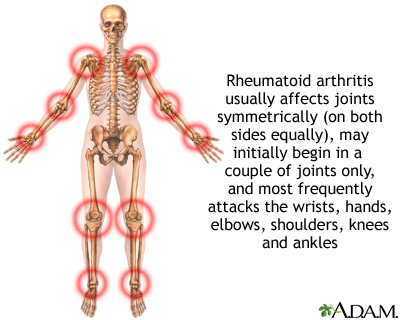

The hallmark symptom of RA is morning stiffness of the joints that lasts at least 1 hour. RA usually first develops in the small joints of the hands, including the wrists, the knuckles, and the base of the fingers. It can also affect feet, ankles, knees, elbows, hips, and shoulders. Joint pain usually affects both sides of the body.

RA can occur at any age. But symptoms typically first appear in middle age (ages 30 to 50).

Women are more likely to develop RA than men.

RA can be difficult to diagnose when it's in its early stages. A doctor will base a diagnosis on a patient's medical history, physical exam, and the results of laboratory tests for specific antibodies.

The treatment of RA involves medications and lifestyle changes (including exercise). The goals are to relieve pain, reduce inflammation, slow joint damage, and improve the patient's quality of life. Disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and biological drugs are the main medications used for rheumatoid arthritis. In addition, it is important to monitor for manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis that occur in other sites than joints.

The American College of Rheumatology's (ACR) drug treatment guidelines for RA recommend:

- The ACR recommends aggressive drug treatment of RA while it is still in its early stages.

- The goal of drug therapy should be to lower disease activity and achieve remission. Patients need individualized treatment goals.

- Drug therapy should be tailored to each patient's individual case. The decision to use single or combination therapy (and which DMARDs or biologic drugs) depends on many factors, including the course and prognosis of the patient's condition.

- Before starting drug therapy, patients should get vaccinated for bacterial infections such as pneumococcal disease, and viruses such as influenza, hepatitis B, human papillomavirus, and varicella zoster.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic disease in which various joints in the body are inflamed, leading to swelling, pain, stiffness, and the possible loss of function.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune disease in which the body's immune system attacks joints and other tissues. The pattern of joints affected is usually on both sides, involves the hands and other joints, and is worse in the morning. RA is a systemic (body-wide) disease, involving other body organs, whereas osteoarthritis is limited to the joints. Both forms of arthritis can be crippling.

RA often develops in the following way:

- The disease process leading to RA begins in the synovium, the membrane that surrounds a joint and creates a protective sac.

- This sac is filled with lubricating liquid called the synovial fluid. In addition to cushioning joints, this fluid supplies nutrients and oxygen to cartilage, a slippery tissue that coats the ends of bones.

- Cartilage is composed primarily of collagen, the structural protein in the body, which forms a mesh to give support and flexibility to joints.

- In rheumatoid arthritis, an abnormal immune system response produces destructive molecules that cause continuous inflammation of the synovium. Collagen is gradually destroyed, narrowing the joint space and eventually damaging bone.

- If the disease develops into a form called progressive rheumatoid arthritis, destruction to the cartilage accelerates. Fluid and immune system cells accumulate in the synovium to produce a pannus, a growth composed of thickened, inflamed synovial tissue.

- The pannus can invade and erode nearby cartilage and bone, aggravating the area and attracting more inflammatory white cells.

- Once cartilage and bone are damaged, the body is unable to repair the damage. Therefore, early treatment is very important.

The chronic inflammatory process associated with RA not only affects cartilage and bones but can also harm organs in other parts of the body.

Causes

Doctors do not know exactly what causes rheumatoid arthritis (RA). The condition is most likely triggered by a combination of factors including an abnormal autoimmune response, genetic susceptibility, and some environmental or biologic trigger such as a viral infection or hormonal changes.

RA is considered an autoimmune disease. Autoimmunity means "immunity against the self." In autoimmune disorders, the body's immune system mistakenly attacks and destroys healthy cells and tissue.

The immune system determines the body's responses to foreign or dangerous substances (antigens) such as viruses, toxins, or abnormal proteins. The immune response helps the body to fight infection and heal wounds and injuries. The inflammatory process is a byproduct of the immune response.

Two important components of the immune system that play a role in the inflammation associated with RA are B cells and T cells, both of which belong to a family of immune cells called lymphocytes. Lymphocytes are a type of white blood cell.

A key feature of a healthy immune system is the ability to tell what is normal or "self" and what is foreign and possibly harmful or "non-self." If the T cell "sees" an antigen as "non-self" or dangerous, it will produce chemicals (cytokines) that cause B cells to multiply and release many immune proteins (antibodies). These antibodies circulate widely in the bloodstream, recognizing the target particles and triggering inflammation in order to rid the body of the invasion.

For reasons that are still not completely understood, both T cells and B cells become overactive in patients with RA and attack normal tissue as if it were foreign. This is why conditions like RA are referred to as "autoimmune" diseases: the body's immune system produces antibodies that attack it.

An antigen is a substance that can trigger an immune response. Normally, antigens are substances that are not present in the healthy body.

Genetic factors may play some role in RA either by increasing susceptibility to developing RA or by making it more severe. The main genetic markers associated with RA are certain HLA (human leukocyte antigen) genes.

A number of HLA genetic forms are associated with rheumatoid arthritis. These genetic factors do not cause RA, but they may make the disease more severe once it has developed.

Infections

Although many bacteria and viruses have been studied, no single organism has been identified as a trigger for RA. Some researchers think an infection may stimulate the immune system to start or prolong RA. Potential infectious triggers include E coli, Mycoplasma, parvovirus B19, retroviruses, mycobacteria, certain bacteria seen with dental infections, and Epstein-Barr virus.

Risk Factors

According to the US Arthritis Foundation, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) affects about 1.5 million Americans.

Although RA can occur at any age from childhood to old age, onset usually begins between the ages of 30 to 50 years.

Women are more likely to develop RA than men.

Some people may inherit genes that make them more susceptible to developing RA, but a family history of RA does not appear to increase an individual's risk.

Long-term smoking is a very strong risk factor for RA, particularly in patients without a family history of the disease.

Severe periodontal disease and chronic infection of the gums is associated with RA and with developing antibodies to an antigen called cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP). People with CCP antibodies have an increased risk of developing a more severe form of RA.

Complications

The course of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) differs from person to person. For some patients, the disease becomes less aggressive over time and symptoms may improve. Other people develop a more severe form of the disease, which can lead to serious complications that affect not only the joints but other areas of the body including organs. Fortunately, for many patients, newer treatments are helping to slow the progression of the disease and prevent severe disability.

Many complications of RA are the result of whole-body (systemic) chronic inflammation.

Affected joints can become damaged and deformed with ongoing active disease. Some patients find it difficult or impossible to perform even ordinary daily tasks. In addition to pain, patients may also experience muscle weakness.

This condition affects the nerves, most often those in the hands and feet. It can result in tingling, numbness, or burning.

People with RA may develop anemia, which involves a reduction in the number of red blood cells. Anemia can cause symptoms such as fatigue and shortness of breath.

Scleritis and episcleritis are inflammations in the eye that can result in corneal damage. Symptoms include redness of the eye and a gritty sensation. Some people with rheumatoid arthritis also have Sjögren syndrome, an autoimmune disorder in which the glands that produce tears and saliva are destroyed. This causes dry mouth and dry eyes.

Patients with RA have a higher risk for infections, both because of the disease itself and the immune-suppressing drugs used to treat it. Before starting treatment with a disease-modifying or biologic drug, patients should receive age-appropriate vaccinations for pneumococcus, influenza, hepatitis B, human papillomavirus, and varicella zoster virus. While taking certain medications for RA, live vaccines are contraindicated. Thus it makes sense to give those vaccines prior to initiating these medications if possible.

Skin problems are common, particularly on the fingers and under the nails. Some patients develop severe skin complications that include rash, ulcers, blisters (which may bleed in some cases), lumps or nodules under the skin, and other problems. In general, severe skin involvement reflects a more serious form of RA.

Osteoporosis, loss of bone density, is more common than average in postmenopausal women with RA. The hip is particularly affected. The risk for osteoporosis also appears to be higher than average in men with RA who are over 60 years old. Corticosteroids (also called steroids) used to treat RA may contribute to osteoporosis.

Patients with RA are susceptible to chronic lung diseases, including interstitial fibrosis, pulmonary hypertension, and other problems. Both RA itself and some of the drugs used to treat it may cause this damage.

Vasculitis involves inflammation in small blood vessels and can affect many organs in the body. Manifestations of vasculitis include mouth ulcers, nerve disorders, rapid worsening of the lungs, inflammation of coronary arteries, and inflammation of the arteries supplying blood to the intestines.

Patients with RA have an increased risk for heart and circulatory conditions including coronary artery disease, heart attack, atrial fibrillation, and stroke. They may also face higher risks for venous thromboembolism (VTE), a condition that includes deep vein thrombosis (formation of blood clots in the veins) and pulmonary embolism (clots in the arteries of the lungs).

Patients with RA are more likely than healthy patients to develop non-Hodgkin lymphoma. RA's chronic inflammatory process may play a role in the development of this cancer. Anti-TNF drugs used for RA treatment may also possibly increase the risk for lymphoma (particularly in children and adolescents) as well as leukemia and other malignancies.

People with RA have a higher risk of developing periodontal disease, which damages the gum and bone around the teeth. (Conversely, severe periodontal disease can also be a risk factor for developing RA.)

Although RA only rarely involves the kidney, some of the drugs used to treat the disease can damage kidneys and the liver.

People with RA can develop AA (or inflammatory) amyloidosis, a condition in which fragments of amyloid A, an inflammatory protein, are deposited in tissues and organs of the body such as the kidney, liver, or spleen.

RA is a painful and frustrating condition. Patients often struggle with depression and anxiety. The stress of dealing with a chronic illness can worsen pain.

Women with RA have an increased risk for premature delivery. They are also more likely than healthy women to develop high blood pressure during the last trimester of pregnancy. For many women with RA, the disease goes into remission during pregnancy but the condition recurs and symptoms can increase in severity after giving birth.

Symptoms

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) symptoms usually develop gradually over the course of weeks or even months. However, rapid onset with more severe symptoms may also occur.

The hallmark symptom of RA is morning stiffness that lasts for at least an hour and sometimes up to several hours. (Stiffness from osteoarthritis, in contrast, usually clears up within half an hour.) Joints may also feel very stiff if not used for long periods of time throughout the day. Warmth or activity can help relieve the stiffness.

Swelling and pain in the joints must occur for at least 6 weeks before a diagnosis of RA is considered. The inflamed joints are usually swollen and often feel warm and "boggy" (spongy) when touched. The pain often occurs on both sides of the body (symmetrically) but may be more severe on one side of the body in some patients.

RA usually first develops in the small joints of the hands, including the wrists, the knuckles, and the base of the fingers. It can also affect feet, ankles, knees, elbows, hips, and shoulders. Many joints may eventually be involved, including those in the upper part of the cervical spine, temporomandibular joint (jaw), and even joints between very small bones in the inner ear.

In some patients with RA, inflammation of small blood vessels can cause nodules, or lumps, under the skin. They are about the size of a pea or slightly larger, firm, and are often located near the elbow, toe, or heel, although they can show up anywhere in the body including in the lungs. Nodules can occur throughout the course of the disease, although they are usually a sign of more severe disease. Rarely, nodules may become sore and infected, particularly if they are in locations where stress occurs, such as the ankles.

Fluid may accumulate, particularly in the ankles. In some cases, the joint sac behind the knee accumulates fluid and forms what is known as a Baker cyst. This cyst feels like a tumor and sometimes extends down the back of the calf causing pain. Baker cysts can also develop in people who do not have RA.

The inflammation associated with RA may also cause general "flu-like" symptoms such as fatigue, loss of appetite, and low-grade fever.

In children, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, which is now known as juvenile idiopathic arthritis, is group of arthritis and inflammatory diseases that occur in children.

Diagnosis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) can be difficult to diagnose. Many other conditions resemble RA. Its symptoms can develop insidiously. Blood tests and x-rays may show normal results for months after the onset of joint pain.

Specific findings or presentation more likely to suggest the diagnosis of RA include morning stiffness, involvement of three joints at the same time, involvement of both sides of the body, subcutaneous (under the skin) nodules, positive test for rheumatoid factor antibodies, and changes in x-rays.

In 2010, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) have developed a joint point-based RA classification system that combines criteria for the joint involvement, serology (autoantibody status), acute phase reactants, and symptom duration. These classification criteria help in the clinical diagnosis of RA.

The ACR has also issued recommendations on additional measures of disease activity, which are used to classify patients for their disease progression, functional status, or disease remission.

Various blood tests may be used to help diagnose RA, determine its severity, and detect complications of the disease.

Rheumatoid Factor

In about 80% of cases of RA, blood tests reveal antibodies in the blood known as rheumatoid factor (RF). RF can also show up in blood tests of people with other autoimmune diseases. However, when it appears with clinical signs and symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis, it is a strong indicator of RA. A negative test does not necessarily rule out RA.

CCP Antibody

A cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) antibody test is often ordered along with a rheumatoid factor test. If people with signs and symptoms of RA test positive for both CCP antibody and rheumatoid factor, it is an indicator that not only do they have RA but they may also develop a more severe or rapidly progressing form of the disease. A positive test for CCP but negative test for RA along with clinical signs and symptoms may suggest early-stage RA or an increased likelihood of developing RA in the future.

Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate

An erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR or sed rate) is a measure of inflammation. The higher the ESR, the greater the inflammation. Because the ESR can be high in many conditions ranging from infection to inflammation to tumors, the ESR test is used not for diagnosis but to help determine how active the RA is.

C-Reactive Protein

A test for C-reactive protein (CRP) may be ordered along with an ESR test. High levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) are also indicators of active inflammation. Like the ESR, a high CRP result does not indicate the source or cause of the inflammation.

Tests for Anemia

Anemia, a reduction in red blood cells, is a common complication of rheumatoid arthritis. Blood tests determine the amount of red blood cells (hemoglobin and hematocrit) and iron (soluble transferrin receptor and serum ferritin) in the blood.

A synovial fluid analysis may help in differentiating RA from other forms of arthritis, such as gout. To perform this test, the doctor inserts a sterile needle into the joint and withdraws the synovial fluid into a syringe attached to the needle. The fluid is sent to a laboratory for analysis.

X-rays in early RA are done to obtain baseline x-rays at the time of diagnosis. Repeat x-rays every 1-2 years can be used to show progression of disease. The doctor may also order other imaging tests, such as ultrasound, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI and ultrasound can give additional information in terms of disease activity that cannot be seen on x-rays. Dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA or DEXA scans), also called bone densitometry, may be used to check for signs of bone density loss associated with osteoporosis.

Symptoms of RA can resemble things as harmless as having slept on a bad mattress or as serious as cancer. Several rare genetic diseases attack the joints. Physical injuries, infections, and poor circulation are among the many problems that can cause aches and pains. Many conditions start with symptoms of joint aches and pains. A few that in particular may be confused with RA arthritis include:

Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis is the most common form of arthritis, but it differs from RA in several important respects:

- Osteoarthritis usually occurs in older people.

- It is located in only one or a few joints. (In fact, osteoarthritis is probably most often confused with RA if it affects multiple joints in the body.)

- The joints are less inflamed.

- Progression of pain is almost always gradual.

- X-rays show changes typical for osteoarthritis.

Gout

Gout also causes swelling and severe pain in a joint. It most commonly starts in one joint. It is sometimes difficult to distinguish chronic gout in older people from rheumatoid arthritis, since gout in this population can occur in a number of joints. A proper diagnosis can be made with a detailed medical history, blood tests, and finding uric acid crystals in the affected joint.

Treatment

The treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) involves medications and lifestyle changes.

Many drugs are used for managing the pain and slowing the progression of RA, but none completely cure the disease. The goals of drug treatment for RA are to reduce disease activity and achieve remission, which includes:

- Reducing inflammation

- Preventing damage to the bones and ligaments of the joint

- Preserving movement

- Helping the patient be as free from side effects as possible over the long term

The drug classes used for RA include:

- Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs). NSAIDs are the least potent drugs used for RA. These drugs relieve pain by reducing inflammation, but they do not affect the course of the disease.

- Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs (DMARDs). DMARDs are the main drugs used for treating rheumatoid arthritis. They slow the progression of the disease. They are much more effective than NSAIDs but also have more side effects. Methotrexate (Rheumatrex, Trexall, generic) is the most widely used of these drugs. Other DMARDs include hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil), sulfasalazine, and leflunomide. Triple therapy including methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine and sulfasalazine can also be used in the treatment of RA.

- Biologic Response Modifiers. These are also known as Biologic DMARDs and are often prescribed to patients who have failed to respond to DMARDs. They may be used alone or in combination with DMARDs such as methotrexate. They modify or block destructive immune factors such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF alpha). Current anti-TNF drugs include infliximab (Remicade), etanercept (Enbrel), adalimumab (Humira), golimumab (Simponi), and certolizumab (Cimzia). Other types of biologic DMARDs that target other molecules include anakinra (Kineret), tocilizumab (Actemra), abatacept (Orencia), rituximab (Rituxan), and sarilumab (Kevzara).

- Small Molecule DMARDs. These are often prescribed either alone or in combination with methotrexate. The only FDA approved small molecule DMARDs are JAK inhibitors. Three JAK Inhibitors are currently approved and these are tofacitinib (Xeljanz), baricitinib (Olumiant), and upadacitinib (Rinvoq). Further research will lead to the development of more Small Molecule DMARDs.

- Corticosteroids. Also called steroids, are powerful anti-inflammatory drugs that are used to quickly reduce inflammation. These drugs include prednisone and prednisolone.

In the past, before current drugs became available, the question of how early and how aggressively to treat RA was the subject of great debate. Some patients with early RA go into remission and remain in remission for the length of their lives even in the absence of treatment. Other patients go on to develop active, sometimes severe RA.

Today, current practice recommends treating the disease aggressively while it is in its early stages to help prevent it from reaching a more severe and chronic state. Studies have found less joint damage in patients with early, aggressive treatment, particularly with the use of DMARDs and biologic DMARDs in combination with methotrexate.

Patients in early stages of RA with moderate symptoms are usually started on a single drug such as methotrexate. Patients with more advanced disease or those who have not been helped by single drug therapy often benefit from a combination of drugs, including other DMARDs, a biologic TNF blocker, or another type of biologic drug.

There is no one-size-fits-all drug treatment approach for rheumatoid arthritis. Your doctor will make a decision on which drug or drugs to prescribe based on:

- How long you have had rheumatoid arthritis

- Your disease activity (symptoms, joint involvement, erythrocyte sedimentation rate)

- If you have other health conditions such as hepatitis, heart failure, or cancer

[For more specific information on drugs, see Medications section of this report.]

Medications

Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) are the standard treatments for rheumatoid arthritis (RA). They are used either alone or in combination with newer biologic DMARDs.

DMARDs do not have any common properties other than their ability to slow down the progression of rheumatoid arthritis. Many were used for other diseases and were found accidentally to help RA. DMARDs include:

- Methotrexate, leflunomide, hydroxychloroquine, minocycline, and sulfasalazine are the DMARDs most commonly prescribed for RA.

- Gold, azathioprine, and cyclosporine are older DMARDs. Cyclosporine and azathioprine are used in specific clinical scenarios and gold is no longer used for rheumatoid arthritis.

Unfortunately, many patients experience a decrease in efficacy of a DMARD after extended periods of therapy. Combining DMARDs with each other or with other types of drugs offers the best approach for many patients.

All DMARDs may produce stomach and intestinal side effects, and, over the long term, each poses some risk for rare but serious reactions. (In some cases, however, they may be less harmful than long-term NSAID treatment.)

Methotrexate

Methotrexate (Rheumatrex, Trexall, Otrexup, Rasuvo, generic) acts as an anti-inflammatory drug and is generally the most frequently used DMARD, particularly for severe disease. Methotrexate starts working within 3 to 6 weeks, but its full effect may not occur until after 12 weeks of treatment.

Even this drug loses effectiveness, however, when used alone. For this reason, it is often used in combination with other DMARDs such as hydroxychloroquine, sulfasalazine (Triple Therapy). It may also be combined with various biological response modifier drugs, especially for treatment of patients with early aggressive arthritis. The combination appears to work better than single drug therapy.

Some patients have to stop taking methotrexate because of its side effects. They include nausea and vomiting, rash, mild hair loss, headache, mouth sores, and muscle aches. Methotrexate reduces levels of folic acid (folate) in the body, which can lead to some of these side effects. Doctors may prescribe folic acid supplements to prevent side effects. However, some research suggests that folic acid may interfere with methotrexate's effectiveness.

Methotrexate is usually given as pills. Patients who need higher doses can take it as an injection. Methotrexate has fewer serious toxic effects than many DMARDs. Although these severe reactions are rare, they may include:

- Bone marrow toxicity. Methotrexate can induce severe and sometimes fatal bone marrow suppression. This effect results in problems with blood cell formation and can lead to anemia or abnormally low levels of white blood cells or platelets.

- Kidney and liver damage. People at particular risk for liver damage from methotrexate include those with diabetes, obesity, and alcoholism. Patients should abstain from alcohol consumption while taking this drug.

- Increased risk for infections. Methotrexate should not be given to patients with active bacterial infections, active herpes-zoster viral infection, active or latent tuberculosis, or acute or chronic hepatitis B or C.

- Lung disease occurs in some people. People who have poor lung function are most at risk.

- The drug increases the risk for birth defects and should not be taken by pregnant women. However, methotrexate will not harm a woman's chance for future healthy pregnancies after she stops taking the drug.

Leflunomide

Leflunomide (Arava, generic) blocks autoimmune antibodies and reduces inflammation. It also may inhibit metalloproteinases (MMP), which are involved in cartilage destruction. Leflunomide takes several weeks before improving joint pain or swelling. Full benefits may not occur until 6 to 12 weeks of treatment.

Leflunomide may be given alone or in combination with other DMARDs such as methotrexate. (This combination poses a risk for liver toxicity and requires monitoring.)

Side effects are similar to those of methotrexate, including nausea, diarrhea, hair loss, and rash. Potentially serious side effects include infections and severe liver injury. Everyone taking leflunomide should be monitored regularly, including blood tests for liver function, and anyone with liver problems should not take this drug. Leflunomide should not be taken by patients with active bacterial infections, active herpes-zoster viral infection, active or latent tuberculosis, or acute or chronic hepatitis B or C. As with methotrexate, the drug increases the risk for birth defects and should not be taken by pregnant women. Patients should not drink alcohol while using leflunomide.

Hydroxychloroquine

Hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil, generic) was originally used for preventing malaria and is now also used for mild, slowly progressive rheumatoid arthritis. Hydroxychloroquine starts to improve symptoms within 1 to 2 months, but it may take up to 6 months to achieve full benefit. Hydroxychloroquine usually causes fewer side effects than other DMARDs but it does not appear to slow disease progression. The most common side effects are nausea and diarrhea, which typically improve over time or when the drug is taken with food. Less common side effects include skin rash or bleaching or thinning of hair.

This drug used to be associated with eye and vision problems, but with current lower doses this side effect is rare. If vision problems occur, it is usually with people taking very high doses, those with kidney disease, or those over 60 years of age. Still, patients should have an eye exam (including retinal examination) within the first year of treatment. Patients on Plaquenil should have frequent eye exams. Patients should notify their doctors if they experience any sudden changes in vision.

Sulfasalazine

Sulfasalazine (Azulfidine, generic) works best when the disease is confined to the joints. Symptom relief occurs within 1 to 3 months.

Side effects are common, particularly stomach and intestinal distress, which usually occur early in the course of treatment. (However, serious gastrointestinal side effects, such as stomach ulcers, occur less frequently with sulfasalazine than with NSAIDs.) A coated-tablet form may help reduce side effects. Other side effects include skin rash and headache. Sulfasalazine increases sensitivity to sunlight. Be sure to wear sunscreen (SPF 15 or higher) while taking this drug. People with intestinal or urinary obstructions or who have allergies to sulfa drugs or salicylates should not take sulfasalazine.

Minocycline

Minocycline (Minocin, generic) is a tetracycline antibiotic that is generally reserved for patients with mild RA. It can take 2 to 3 months before symptoms begin to improve and up to a year for full benefit. Side effects include upset stomach, dizziness, and skin rash. Long-term use of minocycline can cause changes in skin color, but this side effect usually disappears once the medication is stopped. Minocycline can cause yeast infections in women. It should not be used by women who are pregnant or planning on becoming pregnant. Minocycline increases sensitivity to sunlight and patients should be sure to wear sunscreen. In rare cases, minocycline can affect the kidneys and liver.

Gold

Gold used to be a time-honored DMARD for RA but its use has decreased with the development of newer DMARDs and biologic drugs. Gold is usually administered in an injected form because the oral form, auranofin (Ridaura, generic), is much less effective. There are two injectable forms of gold: gold sodium thiomalate (Myochrysine, generic) and aurothioglucose (Solganal, generic). It can take 3 to 6 months before injections have an effect on RA symptoms. Gold injections can cause a number of side effects including mouth sores and skin rash and in rare cases more serious problems such as kidney damage.

Azathioprine

Azathioprine (Imuran, generic) suppresses immune system activity. It takes 6 to 8 weeks for early symptom improvement and up to 12 weeks for full benefit. Azathioprine can cause serious problems with the gastrointestinal tract including nausea and vomiting, often accompanied by stomach pain and diarrhea. Azathioprine can also cause problems with liver function and pancreas gland inflammation and can reduce white blood cell count.

Cyclosporine

Like azathioprine, cyclosporine (Sandimmune, Neoral, generic) is an immunosuppressant. It is used for people with RA who have not responded to other drugs. It can take a week before symptoms improve and up to 3 months for full benefit. The most serious and common side effects of cyclosporine are high blood pressure and kidney function problems. While kidney function usually improves once the drug is stopped, mild-to-moderate high blood pressure may continue. Swelling of the gums is also common. Patients should practice good dental hygiene, including regular brushing and flossing.

Janus Kinase (JAK) Inhibitors

Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors are a newer type of DMARD. Tofacitinib (Xeljanz) was the first in this new class of drugs. It works by blocking "Janus kinase" molecules involved in joint inflammation. Small molecule DMARDs might be an alternative to biologic DMARDs, and a new option for patients with moderate-to-severe RA who have not been helped by methotrexate. Three JAK inhibitors are currently approved and these are tofacitinib (Xeljanz), baricitinib (Olumiant), and upadacitinib (Rinvoq). Several newer investigational drugs that work in a similar same way are being studied. These include Decernotinib, Fostamatinib, and Filgotinib.

Biologic Response Modifiers (Biologic DMARDs)

Biologic response modifiers are drugs made from living cells. These drugs target specific components of the immune system that contribute to the joint inflammation and damage that are part of the RA disease process.

Biologic DMARDs are generally used to treat moderate-to-severe RA. Some of these drugs are used as first-line treatments for RA. Others are used for patients who have not responded to DMARDs or other types of treatment. Depending on the specific drug, they may be used alone or in combination with the DMARD methotrexate. However, biologic response modifiers are not used in combination with each other, as this can lead to serious infections.

As with other RA drugs, these drugs do not cure the disease but can help slow progression and joint damage.

Anti-TNF Drugs

Most biologic DMARDs are anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) drugs. They block TNF, which is a cytokine involved in the inflammatory process. Anti-TNF drugs approved for treatment of RA are:

- Etanercept (Enbrel)

- Infliximab (Remicade)

- Adalimumab (Humira)

- Golimumab (Simponi)

- Certolizumab (Cimzia)

Other Biologic DMARDs

Other biologic DMARDs approved for RA treatment are:

- Tocilizumab (Actemra) blocks interleukin-6 (IL-6), another type of immune factor.

- Abatacept (Orencia) is a T cell co-stimulation modulator, which blocks T cell activation.

- Rituximab (Rituxan) targets CD20-positive B cells and blocks their activation.

- Anakinra (Kineret) targets interleukin-1 (IL-1), but is not as used as often as the other biologic DMARDs.

- Sarilumab (Kevzara) targets the interleukin 6 (IL-6) receptor.

Side Effects and Complications

Etanercept, adalimumab, anakinra, golimumab, certolizumab, and abatacept come in pre-filled syringes and are given by injection under the skin (subcutaneous injection). This may cause pain at the injection site.

Infliximab, tocilizumab, abatacept, and rituximab are given by intravenous infusion in a doctor's office. Common infusion reactions include headache, nausea, and flu-like symptoms. Because biologic response modifiers affect the immune system, patients who take these drugs have an increased risk for infections.

Biologic DMARDs should not be taken by patients with active bacterial infections, active herpes-zoster (shingles) viral infection, active or latent tuberculosis, or active or chronic hepatitis B. Anti TNF drugs should be avoided in patients with acute hepatitis C infection or with chronic hepatitis C infection (treated or untreated) with significant liver injury. In addition, anti-TNF drugs should not be given to patients with a history of heart failure, a history of lymphoma, or who have multiple sclerosis or other demyelinating disorders.

Other risks associated with these drugs include:

- Anti-TNF drugs (etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab, certolizumab) have been associated with sepsis (blood infections), pneumonia, tuberculosis, and other opportunistic and invasive fungal, bacterial, and viral infections. Other risks include non-melanoma skin cancer, lymphoma (Hodgkin disease and non-Hodgkin lymphoma), and other malignancies; lupus; heart failure; blood disorders (including aplastic anemia and leukemia); psoriasis; lung disease; and liver damage.

- Abatacept should be used cautiously in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD) as it may increase the risk for respiratory complications.

- Rituximab has been associated with cases of a rare and deadly brain disease called progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML). It also may cause hepatitis B reactivation, viral infections, heart rhythm disturbances, and other heart problems.

Corticosteroids, also called glucocorticoids or steroids, are powerful drugs that work rapidly to reduce inflammation. Steroids mimic the action of cortisol, a hormone produced naturally in the adrenal gland. For treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, corticosteroids may be given orally by mouth or by injection into a joint.

Oral corticosteroids, such as prednisolone and prednisone (Deltasone, Orasone, generic) are often used in combination with DMARDs. Corticosteroids are often used early in the treatment of active RA since they act rapidly. As the DMARDS begin to reduce activity of RA, the corticosteroids are tapered off and stopped. They may also be used during an acute flare-up.

Side Effects of Oral Corticosteroids

Serious side effects are associated with long-term use of oral steroids. Doctors recommend taking as low a dose as possible. (However, side effects can still occur with daily use of low doses.)

Osteoporosis is a common and particularly severe long-term side effect of prolonged steroid use. Other adverse effects include weight gain, fat deposits, fluid retention and swelling, increased appetite and weight gain, bruising, acne, high blood pressure, cataracts, glaucoma, diabetes, susceptibility to infections, muscle wasting, menstrual irregularities, and mood swings.

Withdrawal from Long-Term Use of Oral Corticosteroids

Long-term use of oral steroid medications suppresses secretion of natural steroid hormones by the adrenal glands. After withdrawal from these drugs, this adrenal suppression persists and it can take the body a while (sometimes up to a year) to regain its ability to produce natural steroids again.

No one should stop taking any steroids without consulting a doctor first, and if steroids are withdrawn, regular follow-up monitoring is necessary. Patients should discuss with their doctor measures for preventing adrenal insufficiency during withdrawal, particularly during stressful times, when the risk increases.

Two-thirds of people with RA rank pain as their primary reason for seeking professional help. The most common pain relievers for RA are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). These drugs block prostaglandins, the substances that widen blood vessels and cause inflammation and pain. There are dozens of NSAIDs:

- Over-the-counter NSAIDs include aspirin, ibuprofen (Motrin, Advil, generic), naproxen (Aleve, generic), ketoprofen (Actron, Orudis KT, generic).

- Prescription NSAIDs include prescription forms of ibuprofen, naproxen, and ketoprofen, flurbiprofen (Ansaid, generic), diclofenac (Voltaren, generic), and tolmetin (Tolectin, generic). Meloxicam (Mobic, generic) is approved specifically for the management and treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Duexis is a pill that combines ibuprofen and the H2 blocker famotidine (Pepcid, generic) that is also approved specifically for rheumatoid arthritis, and osteoarthritis.

Studies suggest that the best times for taking an NSAID may be after the evening meal and then again on awakening. RA symptoms increase gradually during the night, reaching their greatest severity at the time of awakening. Taking NSAIDs with food can reduce stomach discomfort, although it may slow the pain-relieving effect.

Long-term, regular use of NSAIDs (with the exception of aspirin) can increase the risk for heart attack, especially for people who have a heart condition. Long-term use of NSAIDs also increases the risk for ulcers and gastrointestinal bleeding. This risk can be reduced by taking antacid medication such as omeprazole (Prilosec, generic) along with the NSAID. To reduce the risks associated with NSAIDs, take the lowest dose possible for pain relief.

Other possible side effects of NSAIDs may include:

- Upset stomach

- Diarrhea or constipation

- Skin bruising

- High blood pressure

- Fluid retention

- Headache

- Rash

- Reduced kidney function

COX-2 Inhibitors (Coxibs)

Coxibs inhibit an inflammation-promoting enzyme called COX-2. This drug class was initially thought to provide benefits equal to NSAIDs but cause less gastrointestinal distress. However, following numerous reports of heart problems, skin rashes, and other adverse effects, the FDA re-evaluated the risks and benefits of COX-2 inhibitors. Several coxib drugs were removed from the United States market. Celecoxib (Celebrex) is still available, but patients should ask their doctors whether the drug is appropriate and safe for them. Like all NSAIDs, celecoxib has a "black box" warning on its prescribing label that it may increase the risk for heart attack, stroke, and serious stomach problems.

Surgery

Some people with RA benefit from joint surgery. Surgery can help relieve joint pain, correct deformities, and modestly improve joint function. There are several types of joint surgery techniques.

Synovectomy is removal of the joint lining (synovium). It is used to remove inflamed tissue that causes pain. Synovectomy can help reduce swelling and slow the progression of joint damage.

The procedure may be performed on joints in the knees, elbows, wrists, fingers, or hips. Synovectomy may be performed as open surgery (arthrotomy) or arthroscopically (arthroscopic synovectomy).

Arthroscopy is a surgical procedure that uses a small lighted tube with a camera (called an arthroscope), which is inserted in the joint. A fiber-optic cable attached to the arthroscope allows the surgeon to view the inside of the joint on a monitor.

Arthroscopy can be used to perform different procedures including synovectomy. It may also be used to clean out bone and cartilage fragments (a process called debridement) that cause pain and inflammation.

Eventually, even after these procedures, RA may progress to the point that normal functioning is impossible. In such cases, artificial (prosthetic) replacement joint implants may be considered for shoulders, knees, hips, ankles, wrists and hands, or other joints.

Joint replacement (arthroplasty) is usually reserved for people over age 50 or those whose joint damage is rapidly progressing. The joint replacement typically lasts for 20 years or more.

If the affected joint cannot be replaced, surgeons can perform a procedure called arthrodesis that eliminates pain by fusing the bones together. However, fusing the bones makes movement of the joint impossible. Bone fusion is most often done in the spine and in the small joints of the hands (wrists, fingers) and feet (ankles, toes).

Lifestyle Changes

Lifestyle changes can help patients deal with the physical and emotional aspects of living with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

It is important for patients with RA to maintain a balance between rest (which will reduce inflammation) and moderate exercise (which will relieve stiffness and weakness). Studies have suggested that even as little as 3 hours of physical therapy over 6 weeks can help people with RA, and that these benefits are sustained.

The goal of exercise is to:

- Maintain a wide range of motion

- Increase strength, endurance, and mobility

- Improve general health

- Promote well-being

In general, doctors recommend the following approaches:

- Start with the easiest exercises, stretching and tensing of the joints without movement.

- Next, attempt mild strength training.

- The next step is to try aerobic exercises. These include walking, dancing, or swimming, particularly in heated pools. Avoid heavy impact exercises, such as running, downhill skiing, and jumping.

- Tai chi, which uses graceful slow sweeping movements, is an excellent method for combining stretching and range-of-motion exercises with relaxation techniques. It may be of particular value for older patients with RA.

A common-sense approach to exercise is the best guide:

- If exercise is causing sharp pain, stop immediately.

- If lesser aches and pains continue for more than 2 hours afterward, try a lighter exercise program for a while.

- Using large joints instead of small ones for ordinary tasks can help relieve pressure, for instance, closing a door with the hip, or pushing buttons with the palm of the hand.

Many patients with RA try dietary approaches, such as fasting, vegan diets, or eliminating specific foods that seem to worsen RA symptoms. There is little scientific evidence to support these approaches but some patients report that they are helpful.

In recent years, a number of studies have suggested that the omega-3 fatty acids contained in fish oil may have anti-inflammatory properties useful for RA joint pain relief. The best source of fish oil is through increased consumption of fatty fish such as salmon, mackerel, and herring. Fish oil supplements are another option, but they may interact with certain medications. If you are thinking of trying fish oil supplements, talk to your doctor first.

Patients can learn strategies to cope with the stress and frustration of living with chronic pain. Relaxation and stress management techniques such as guided imagery, breathing exercises, hypnosis, or biofeedback can be helpful.

Although there is no definitive evidence to support their efficacy, some patients report relief with modalities such as acupuncture, massage, and mineral baths.

There are many different types of assisted devices that can help make life easier in the home. Kitchen gadgets, such as jar openers, can assist with gripping and grabbing. Door-knob extenders and key turners are helpful for patients who have trouble turning their wrists. Bathrooms can be fitted with shower benches, grip bars, and raised toilet seats. An occupational therapist can advise you on choosing the right kinds of assistive devices.

Various ointments, including Ben Gay and capsaicin (a cream that uses the active ingredient in chili peppers), may help soothe painful joints.

Orthotic devices are specialized braces and splints that support and help align joints. Many such devices made from a variety of light materials are available and can be very helpful when worn properly.

Like all chronic illnesses, RA poses many frustrations and challenges -- physical, emotional, financial, and otherwise. It affects all dimensions of a person's life including work, family, and relationships. In addition, many patients with RA are diagnosed while in their prime adult years, when they may have responsibilities for taking care of children or older parents.

It is absolutely normal and natural for patients to feel overwhelmed, especially after first receiving a diagnosis. It is important to know that the newer medications, when started early for RA, have markedly improved the long-term outlook for RA. Specialists called rheumatologists are most familiar with these medications and treatments for RA.

The following are some tips for living and coping with RA:

- Learn More About Your Illness. The more you know about RA, the better you can manage it. Ask your rheumatologist for reliable resources (websites, national organizations, support groups). Remember that what may be confusing at first will start to make sense.

- Be Gentle with Yourself. Remind yourself that you will adapt over time. You will get used to the "new normal." You will feel like yourself again as you learn how to fit your illness into your life.

- Pace Yourself. Fatigue and low energy are common with rheumatoid arthritis. Medications can have side effects. When RA flares, the pain can interfere with many normal activities. All of these things can take an emotional toll and can deplete your energy. Listen to your body and rest when you need to. Assure yourself that the range of feelings you experience is normal. Simple activities that relieve stress (going for a walk, spending time with a friend, taking an art class) can help improve your energy and mood. Share with your doctor any concerns you have about depression.

- Talk With Others Who Have RA. Know that you have much to share and learn from others who have this condition and who are going through similar challenges. Your hospital may have a support group. There are also online groups including specialized ones such as for mothers with RA.

- Let Others Help You. Keep a list of people who you can ask for help. Inform your friends and loved ones how they can specifically help you. Many people are happy to help and are glad to be asked.

Resources

- National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases -- www.niams.nih.gov

- American College of Rheumatology -- rheumatology.org

- Arthritis Foundation -- www.arthritis.org

References

Aletaha D, Smolen JS. Assessment of the patient with rheumatoid arthritis and the measurement of outcomes. In: Hochberg MC, Gravallese EM, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, Weinblatt ME, Weisman MH, eds. Rheumatology. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019:chap 101.

Aletaha D, Smolen JS. Diagnosis and Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Review. JAMA. 2018;320(13):1360-1372. PMID: 30285183 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30285183/.

Anderson J, Caplan L, Yazdany J, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis disease activity measures: American College of Rheumatology recommendations for use in clinical practice. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64(5):640-647. PMID: 22473918 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22473918/.

Brasington RD, Miner JJ. Clinical features of rheumatoid arthritis. In: Hochberg MC, Gravallese EM, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, Weinblatt ME, Weisman MH, eds. Rheumatology. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019:chap 94.

Burmester GR, Pope JE. Novel treatment strategies in rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 2017;389(10086):2338-2348. PMID: 28612748 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28612748/.

Cramp F, Hewlett S, Almeida C, et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(8):CD008322. PMID: 23975674 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23975674/.

England BR, Tiong BK, Bergman MJ, et al. 2019 Update of the American College of Rheumatology Recommended Rheumatoid Arthritis Disease Activity Measures. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2019;71(12):1540-1555. PMID: 31709779 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31709779/.

Erickson AR, Cannella AC, Mikuls TR. Clinical features of rheumatoid arthritis. In: Firestein GS, Budd RC, Gabriel SE, McInnes IB, O'Dell JR, eds. Kelley and Firestein's Textbook of Rheumatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017:chap 70.

Firestein GS. Etiology and pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. In: Firestein GS, Budd RC, Gabriel SE, McInnes IB, O'Dell JR, eds. Kelley and Firestein's Textbook of Rheumatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017:chap 69.

Lamb SE, Williamson EM, Heine PJ, et al. Exercises to improve function of the rheumatoid hand (SARAH): a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9966):421-429. PMID: 25308290 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25308290/.

Lau CS, Chia F, Dans L, et al. 2018 update of the APLAR recommendations for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2019;22(3):357-375. PMID: 30809944 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30809944/.

Liao KP. Classification and epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis. In: Hochberg MC, Gravallese EM, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, Weinblatt ME, Weisman MH, eds. Rheumatology. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019:chap 92.

Lopez-Olivo MA, Amezaga Urruela M, McGahan L, Pollono EN, Suarez-Almazor ME. Rituximab for rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;1:CD007356. PMID: 25603545 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25603545/.

Mason JC. Rheumatic diseases and the cardiovascular system. In: Zipes DP, Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Tomaselli GF, Braunwald E, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019:chap 94.

Mcinnes I, O’Dell JR. Rheumatoid arthritis. In: Goldman L, Schafer AI, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 26th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2020:chap 248.

O'Dell JR. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. In: Firestein GS, Budd RC, Gabriel SE, McInnes IB, O'Dell JR, eds. Kelley and Firestein's Textbook of Rheumatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017:chap 71.

Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL Jr, et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(1):1-26. PMID: 26545940 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26545940/.

Smolen JS, Aletaha D, McInnes IB. Rheumatoid arthritis [published correction appears in Lancet. 2016 Oct 22;388(10055):1984]. Lancet. 2016;388(10055):2023-2038.PMID: 27156434 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27156434/.

Reviewed By: Diane M. Horowitz, MD, Rheumatology and Internal Medicine, Northwell Health, Great Neck, NY. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.