Melanoma and other skin cancers - InDepth

Highlights

Overview

- The skin is the largest organ in the body and is composed of several cell types. Skin cancer, in various forms, is the most common cancer. Different skin cancers start in different cells of the skin.

- Based on the type of cell in which they originate, skin cancers are divided into two major groups: melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancers. Nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) includes basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Melanoma, derived from melanocytes, is the deadliest form of skin cancer.

- Over 2 million new cases of nonmelanoma skin cancer occur each year in the United States.

- The incidence of melanoma has increased by close to 10 times over the last 20 to 30 years and is increasing in frequency in people under the age of 40.

Risk Factors

- Sunlight is the most important environmental cause of melanoma and other skin cancers, as well as premature skin aging (photoaging).

- The risk of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer rises with more frequency and length of time using indoor tanning devices, especially when tanning starts young (in the teenage and early 20s). Newer tanning technology does not appear to be any safer than older tanning beds. The World Health Organization has labeled tanning beds a carcinogen.

- Some studies have found that taking aspirin is associated with a lower risk of melanoma in women but may increase the risk of melanoma in men. However, many studies contradict one another and aspirin can have unwanted side effects. More research is needed to assess benefits, risks, dosages, and timing of aspirin.

- People with a family history of melanoma have approximately twice the risk of developing melanoma as those without a family history. Some genetic defects have been identified but there are others that remain unknown.

- A genetic mutation in a gene called BRAF occurs in approximately 50% of patients with advanced melanoma.

New Drugs/Vaccines

- A number of biologic agents have been approved or are being studied for the treatment of high-risk melanoma.

- Several therapeutic melanoma vaccines are in the advanced stages of testing, and a few combined vaccine and biologic therapies have recently been approved for use in patients with inoperable, recurrent, or metastatic melanoma.

Prevention

- The best way to lower your risk for skin cancer is to protect your skin from the sun and UV light.

- Use sunscreens that block out both UVA and UVB radiation (broad spectrum protection). Reapply every 2 hours while out in the sun or after swimming or sweating.

- Do not rely on sunscreen alone for sun protection. Also wear protective clothing, hats, and sunglasses.

Introduction

Skin cancer is cancer that starts in the skin cells. Skin cancers are divided into two major groups:

- Nonmelanoma skin cancer, which includes basal cell cancer and squamous cell cancer

- Melanoma, the deadliest form of skin cancer

Different skin cancers start in different cells of the skin. To understand how skin cancer develops, it is useful to understand the structure of the skin.

The skin is the largest organ in the body and consists of layers.

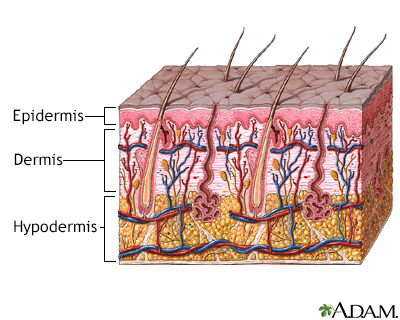

- The outermost layer of the skin is called the

epidermis

. It is only about 20 cells deep, roughly as thick as a sheet of paper. - The

dermis

ranges in thickness from 1 to 4 millimeters (about 1/32 to 1/8 inch). The dermis contains tiny blood and lymph vessels, which increase in number deeper in the skin. - Lying right underneath the dermis is the

hypodermis

, the deepest layer of the skin. It varies in thickness depending on the body region. The hypodermis contains adipose tissue (fat) and connective tissue that helps to attach the skin to the underlying muscles and bones. Melanocytes

. A layer of cells between the epidermis and the dermis calledmelanocytes

produces a brown-black skin pigment (melanin

) that determines skin and hair color. Melanin also helps protect against the damaging rays of the sun.

The skin is the largest organ of the body. The skin and its components (hair, nails, sweat, and oil glands) make up the integumentary system. One of the main functions of the skin is protection. It protects the body from external factors, such as bacteria, chemicals, and temperature. The skin contains secretions that can kill bacteria, and the pigment melanin provides a chemical defense against ultraviolet light that can damage skin cells. The skin also helps control body temperature.

As a person ages, melanocytes often multiply (proliferate). They form clusters that appear on the skin surface as small, dark, flat, or dome-shaped spots, which are often harmless sunspots called lentigo. While they have nothing to do with the liver, they are often called "liver spots."

- When cell proliferation occurs in a controlled and contained manner, the resulting spot is noncancerous (benign) and is commonly referred to as a mole or

nevus

. - Sometimes, however, pigment cells grow out of control and become a cancerous and life-threatening melanoma.

Melanoma

Melanoma accounts for only about 1% of all skin cancers, yet it results in the most skin cancer deaths, according to the American Cancer Society (ACS). The incidence of melanoma has increased by close to 10 times over the last 20 to 30 years.

At first, melanoma cells are found in the epidermis and top layers of the dermis. However, once they grow downward into the dermis, the cancer can come into contact with lymph and blood vessels, and from there spread (metastasize) to other parts of the body. The thicker the melanoma, the greater the likelihood that it could spread to distant sites. There are also other factors and proteins expressed by the cancer that allow it to spread and invade blood vessels.

Removing the lesion before it reaches the deeper layers of the skin where it can invade into the blood vessels is important to achieve a cure and minimize the chance of metastasis.

Specific Melanomas

Melanoma in situ

Melanoma in situ is the earliest form of melanoma when the cancer is confined to the epidermis, the top layer of the skin. Because the cancerous cells have not invaded into the dermis, this type is cured surgically with minimal risk for metastasis.

Superficial Spreading Melanoma

Superficial spreading melanoma is the most common type of melanoma. It is flat, asymmetrical, unevenly colored, and usually grows laterally across the surface of the skin. Superficial spreading melanoma accounts for about 70% of melanomas. In men, it occurs most often on the upper back. In women, it is most likely to be seen on the back of the leg. The reason for these locations remains unclear.

Nodular Melanoma

Nodular melanoma appears as a fast-growing brown or black lump, and its characteristics do not always fit the definitions described above. Nodular melanoma accounts for about 5% of melanomas. It is usually seen on the trunk or limbs.

Lentigo Maligna

Lentigo maligna (sometimes called Hutchinson freckle) usually occurs in older people and is marked by flat, mottled, tan-to-brown freckle-like spots with irregular borders. These lesions often appear on the face or other sun-exposed areas and typically grow slowly for 5 to 15 years before cancer appears. Lentigo maligna melanoma accounts for 4% to 15% of melanoma cases.

Acral Lentiginous Melanoma

Although rare, acral lentiginous melanoma is the most common melanoma among African and Asian populations. It commonly appears as a dark patch on the palms, soles, fingers, or toes, under fingernails or toenails, or in mucous membranes.

Several other types of melanomas exist, but they are relatively uncommon.

Growth Pattern

Melanoma cells often spread first through the lymph vessels or glands. Melanoma cells can also spread by way of blood vessels to various organs, carrying cancer to the liver, lungs, brain, or other sites.

Melanomas tend to grow in stages:

- Most melanomas tend to be flat at first and spread across the skin surface as they grow. At this early stage, which can last 1 to 5 years or longer, removing the growth has an excellent chance of curing the melanoma. Still, there is a possibility that some of these melanomas have cells that have penetrated deeper into the skin, and they should be treated aggressively.

- Lesions that become raised or dome-shaped over at least part of their surface indicate that downward growth has occurred. In some cases, this growth is very rapid, occurring over a period of weeks to months. As a result, these cancers are more aggressive and more likely to spread.

Any suspicious lesion should be checked immediately, especially if it has grown quickly or is partially flat and partially raised.

Location

Common sites of melanoma in men include:

- Upper back (most common)

- Head

- Neck

- Middle of the body (trunk)

Common sites of melanoma in women include:

- Back of the legs (most common)

- Arms and front of the legs

However, melanoma can affect any area of the skin. You may not notice melanomas if they appear on areas that are difficult to examine, such as the scalp or back or bottom of the foot.

Less common sites for melanoma include:

- Fingers

- Genitals

- Lips

- Palms

- Soles of the feet

- Under the fingernails or toenails

A dark lesion under the nail that runs into the nearby skin and doesn't heal may be a sign of melanoma. Darkening of the cuticle in the presence of a dark streak in the nail is a sign of melanoma.

Rarely, melanomas appear in the mouth, iris of the eye, or retina at the back of the eye, where they may be found during dental or eye examinations. While quite rare, melanoma can also develop in the mucous membranes, such as the vagina, esophagus, anus, urogenital tract, and small intestines.

Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer

Other types of skin cancer are referred to as nonmelanoma skin cancers. The two most common types are called basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma.

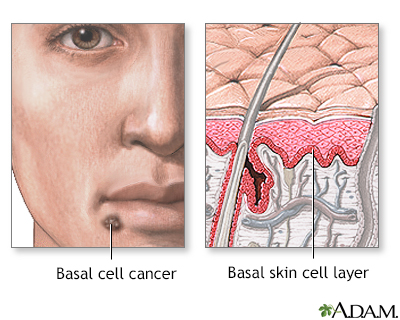

Basal Cell Cancer

Basal cell carcinoma starts in the lowest part of the epidermis, in round cells called basal cells that form the base of the epidermis. Basal cell carcinoma is the most common form of skin cancer. However, this cancer is rarely fatal and rarely metastasizes. The death rate from nonmelanoma skin cancers has dropped about 30% over the past 30 years.

Basal cell carcinoma often develops later in life in areas that have received the most sun exposure, such as the head, neck, and back. However, some basal cell carcinomas appear in areas not exposed to the sun.

Basal cell carcinomas have many different appearances:

- They most often appear as a round area of thickened skin that does not change color or cause pain or itching. However, the superficial form can appear rash-like, being a red and scaly patch that just will not heal.

- Very slowly, the lesion spreads out and develops a slightly raised edge, which may be translucent and smooth with dilated blood vessels. Rarely, basal cell carcinomas have a similar color to malignant melanomas. These are called pigmented basal cell carcinomas.

- Eventually, the center becomes hollowed and covered with a thin skin, which can become sore and open.

- A form known as morpheaform or sclerosing basal cell carcinoma is an aggressive-growth basal cell carcinoma that looks like a scar with a hard base. This type of cancer is more likely to spread and must be treated very aggressively.

Basal cell carcinoma is a cancerous (malignant) skin tumor involving basal skin cells. Basal cell skin cancers usually occur on areas of skin that are regularly exposed to sunlight or other ultraviolet radiation. Once a suspicious lesion is found, a biopsy is needed to diagnose basal cell cancer. Treatment varies depending on the size, depth, and location of the cancer.

Basal cell carcinomas are sometimes hard to tell from benign skin conditions. For instance, occasionally they arise in unexposed skin, where they may look like an ordinary mole, cyst, or pimple. They may be particularly difficult to tell apart from benign cysts when they occur near the eyes.

Usually, basal cell carcinomas grow slowly. They are rarely deadly. Most basal cell cancers do not need to be treated as an emergency. However, because late treatment can cause disfigurement, they should be removed as early as possible.

Basal cell carcinomas that are most likely to spread include those that are larger than 1 centimeter, scar-like, and those located on the cheek, nose, neck, earlobe, eyelid, or temple.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Bowen Disease

Squamous cell carcinoma of the skin is the second most common type of skin cancer.

Squamous cell carcinoma develops from flat, scale-like skin cells called keratinocytes, which lie on top of the basal cell layer of the epidermis. Most squamous cell carcinomas occur on sun-exposed areas, largely the forehead, temple, ears, neck, and back of the hands. Burns or other heat-related injured sites are more likely to develop squamous cell carcinoma. People who have spent considerable time sunbathing may develop them on their lower legs. Squamous cell carcinomas occur more often than basal cell cancers in African Americans and Asians, and are more common in men than women.

Although squamous cell skin carcinomas usually can be removed completely with no risk of the cancer spreading, they are more likely than basal cell cancers to be invasive and spread elsewhere in the body.

Types of squamous cell carcinoma:

- Squamous cell carcinoma in situ (also called

Bowen disease

) is the earliest form of this type of cancer. The cancer is confined to the epidermis and has not invaded the deeper dermis. Cancer areas can appear as reddish patches (often over 1 inch or 2.5 centimeters) that are scaly and crusted. They can look like warts. - Invasive squamous cell carcinoma is more likely to spread. The skin cancer lesions can grow rapidly (over weeks to months) or slowly (over years). Eventually they break into an open wound (become ulcerated) that will not heal.

Getting prompt treatment is important, because squamous cell cancers are more likely than basal cell cancers to spread to local lymph nodes.

Squamous cell cancers most likely to spread include:

- Deep lesions, or patches with poorly defined borders

- Large lesions (larger than 2 cm in diameter)

- Lesions that keep returning

- Squamous cell carcinoma on the hands, neck, earlobe, eyelid, lips, or temple

- Squamous cell carcinoma that develops in ulcers

- Squamous cell cancer that develops on skin areas that have been treated with radiation or exposed to cancer-killing chemicals (chemotherapy)

- Poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, a more aggressive subtype

People who have had basal cell or squamous cell skin cancers are at increased risk of developing other types of cancer, including:

- Bladder cancer

- Breast cancer in women

- Leukemia

- Lung cancer

- Melanoma

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- Testicular and prostate cancer in men

The younger people are when they get nonmelanoma skin cancer, the higher their risk of developing other cancers.

Merkel Cell Carcinoma

Merkel cell carcinoma is another type of non-melanoma skin cancer. It is rare, but when it occurs, it tends to spread fast.

Merkel cell carcinoma begins in Merkel cells, a type of skin receptors that are responsible for sensing light touch. These cells are located at the base of the epidermis, the outermost skin layer. It was recently found that infection with a virus called Merkel cell polyoma virus may be the cause of most of these cancers.

The following factors may increase your risk for Merkel cell carcinoma:

- Older age

- Fair skin

- Certain medical conditions or treatments that weaken your immune system

- History of other kinds of skin cancer

- Too much exposure to sunlight and ultraviolet radiation, including indoor tanning

Merkel cell carcinoma usually appears as a firm bluish-red swelling or lump and is often located on the head or neck, in areas that are most exposed to the sun.

Precancerous Skin Conditions

Actinic (Solar) Keratosis

Actinic keratosis (also called solar keratosis) is considered to be a precancerous skin lesion caused by chronic or excessive sun exposure. There is an increased risk of skin cancer in patients who have these lesions, but the risk of one specific actinic keratosis turning into squamous cell carcinoma is about 5%. The increased risk of cancers may be due to the fact that heavy sun exposure has been linked to both actinic keratosis and nonmelanoma skin cancers.

Actinic keratosis occurs after years of sun exposure. It appears mostly on sun-exposed skin, such as the face, neck, back of the hands and forearms, upper chest, and upper back. Men may develop keratosis along the rim of the ear.

Actinic keratosis has the following characteristics:

- Lesions typically occur on the surface of the skin and have a sandpaper-like feel. They are sometimes more easily felt than seen.

- Most lesions are pink or flesh-colored. Some are red or brown, scaly, and tender. At times, they can resemble melanomas; even dermatologists may have trouble telling the two apart.

- They can range in size from microscopic to several inches in diameter.

Keratoacanthomas

Keratoacanthomas closely resemble squamous cell cancers and many consider them to be a subset of squamous cell carcinoma. Most of these occur in sun-exposed skin, usually on the hands or face. They are typically skin colored or slightly red when they first develop, but their appearance typically changes:

- In the early stages, keratoacanthomas are smooth, red, and dome shaped.

- Within a few weeks, they can grow rapidly, usually to 1 or 2 centimeters. Some reach the size of a quarter in less than a month and can be disfiguring.

- They eventually stop growing and become crater-like, with a surrounding outer rim of tissue and sometimes a crusty interior.

- They are often confused with a boil or an infection.

Some will get better on their own within 1 year, but they almost always scar after healing. Removal by surgery (sometimes by radiation) is recommended. They may also be treated with 5-fluorouracil, either as a cream or injections.

Causes

The sun is the most important cause of prematurely aging skin (

photoaging

) and skin cancers.Long-term, repeated exposure to sunlight appears to be responsible for most undesirable consequences of aging skin, including basal cell and squamous cell cancers.

Melanoma is more likely to be caused by intense exposure to sunlight in early life.

UVA and UVB Radiation

When sunlight penetrates the top layers of skin, ultraviolet (UVA or UVB) radiation strikes the DNA inside the skin cells and damages it.

- UVB is the main type of radiation responsible for sunburns. It primarily affects the outer skin layers. This type of ultraviolet light is most intense at midday when sunlight is brightest.

- UVA penetrates more deeply and efficiently. Although window glass filters out UVB, it does not necessarily protect against UVA rays. UVA causes many of the signs of aging of the skin and skin cancers. While it is not as carcinogenic as UVB, we receive much more UVA exposure.

Damaging Effects of UV Radiation

Both UVA and UVB rays cause damage, including genetic injury, wrinkles, lower immunity against infection, aging skin disorders, and cancer, although the mechanisms are not yet fully clear. The following are some ways in which cancer may develop, and some actions the skin uses to defend itself against DNA damage.

Oxidation and Antioxidants

. UV radiation promotes the production ofoxidants

, also called free radicals. Free radicals are unstable molecules produced by normal chemical processes in the body that, in excess, can damage the body's cells and even alter the DNA. This contributes to the aging process and sometimes to cancer. Vitamin C applied topically to the skin is a good antioxidant that helps protect the skin from the damaging free radicals.Defective DNA Repair and Protective Enzymes

. Some skin cancers are caused by a breakdown in the body's mechanisms that help repair DNA damage. For example, xeroderma pigmentosum (XP) is a rare genetic disease in which the body cannot repair damage caused by ultraviolet light, and affected people get numerous squamous cell carcinomas even at a young age. Normally, a number of enzymes in the skin help protect against this damage.Breakdown of Immune Protection

. Specific immune factors protect the skin, including white blood cells called T lymphocytes and specialized skin cells called Langerhans cells. These immune system cells attack developing cancer cells at the very earliest stages. However, certain substances in the skin, particularly a chemical called urocanic acid, can suppress such immune factors when exposed to sunlight.

Defective Cell Death (Apoptosis)

Apoptosis is the last defense of the immune system. It is a natural process of cell suicide, which occurs when cells are very severely damaged. Apoptosis in the skin kills off cells harmed by UVA so that they do not turn cancerous. The peeling after sunburn is the result of these dead skin cells. However, some gene defects or other factors can interfere with apoptosis. If this occurs, damaged cells can continue to spread, resulting in skin cancer.

Risk Factors

According to the American Cancer Society, the lifetime risk of getting melanoma is about 2% (1 in 50) for White people, 0.1% (1 in 1,000) for Black people, and 0.5% (1 in 200) for Hispanic people. The number of melanoma cases has been increasing over the past 30 years.

Survival rates have been improving, however, and the increase in melanomas has occurred mainly with less aggressive forms of the disease. Some experts believe this is due to earlier diagnosis and increased awareness of the disease, resulting from effective public health programs.

The following factors increase your risk for skin cancer:

- Age over 40

- Male sex

- Fair skin

- Too much exposure to sunlight and ultraviolet radiation, including indoor tanning

- High mole count, particularly on the arms

- Personal history of skin cancer

- Family history of skin cancer

- Smoking

- Certain chronic or severe skin problems

- Certain medical conditions or treatments that affect your immune system

- Exposure to chemicals or radiation

- Taking TNF-alpha blockers to treat rheumatoid arthritis or other illnesses

Age and Sex

Aging may weaken the body's ability to fend off cancers, including melanomas. As a person ages, they lose Langerhans cells that help fight off early skin cancers, possibly setting the stage for skin cancers in later life.

Melanoma in Adults

Melanoma is most common in people over 40 years, although it also can affect young and middle-aged people. The average age at diagnosis is 57 years. Men are more likely to have invasive and fatal melanoma than women, although some research suggests that the higher rates are only because men fail to get suspicious skin changes diagnosed before they become dangerous. The rate in women levels off somewhat after age 50 years; researchers think menopause could have some sort of protective effect.

Melanoma in Children

Melanoma is rare in children under age 10 years. Among children ages 10 to 19 years, it is more common but still rare. Parents should not be too alarmed by every minor skin imperfection in their children but should certainly talk to a dermatologist about any mole that changes rapidly or appears much different than the child's other moles. Children are growing and changing so moles on kids will grow and change normally. However, melanoma is as serious in children as it is in adults, and early detection is still critical. It is also noteworthy that the incidence of melanoma in children and adolescents has been steadily increasing.

Nonmelanoma skin cancers are rare in children and young adults, but they begin to increase significantly in middle age and older. However, the sunlight that one gets when young causes the skin cancers that arise in adulthood.

Sunlight and Ultraviolet Radiation Exposure

Skin cancer is associated with both the length and intensity of sun exposure. The risk of melanoma increases with excessive sun exposure during the first 10 to 18 years of life. Sunburns are also dangerous; having 5 or more sunburns doubles the risk of developing skin cancer. The cancer typically arises many years later.

Tanning Devices

Tanning beds and sun lamps increase the risk for developing melanoma and other skin cancers, and the risk increases with frequency, age of use, and length of use. Women in their 20s, as well as people with blond or red hair are especially at risk. The World Health Organization has designated tanning devices as known carcinogens. More governmental restrictions are now in place to prevent young people from accessing these devices.

Phototherapy and Photochemotherapy with PUVA

There is some evidence that long-term treatment for psoriasis and other skin conditions using UVA radiation (PUVA) and UVB may increase the risk for melanoma. If phototherapy is part of your treatment plan for skin disease, one should talk with the dermatologist about the risk of skin cancer developing and be checked regularly.

Ethnic Groups and Complexion

People with light skin; blue, gray, or green eyes; red or blond hair; and lots of freckles are at highest risk for developing all types of skin cancers. The risk increases for those who easily sunburn and rarely tan, particularly if they live close to the equator where sunlight is most intense. However, people with darker complexions are not immune as tanned skin is also sun-damaged skin. In fact, they are often seen by a doctor at a later stage of the disease, resulting in a worse prognosis. People of color must still practice good prevention, such as self-examination, sunscreen, sun protective clothing, avoiding tanning beds, and early detection and treatment by a physician.

Geographic Location

Geography plays a role in skin cancer risk, primarily with regard to the intensity and length of sun exposure in certain locations. Studies show an increased incidence of melanomas in populations that previously had a lower incidence, but then migrated to Australia.

Genetic Factors

People with certain genetic characteristics, such as blue or green eyes, or blonde or red hair, have an increased risk for skin cancers.

Patients diagnosed with melanoma who have a family history of melanoma or nevi are considered to be at increased risk for more invasive cancers. A number of genetic factors are being investigated for their role in the formation of melanomas, including inherited genes and genetic defects that are acquired through the environment (particularly sunlight).

Your genetic makeup and whether or not certain genes mutate in your body can increase your risk of developing melanoma and other skin cancers. More studies need to be done to identify which genes play a role and how these affect one's likelihood of developing a skin cancer.

A genetic mutation in a gene called BRAF occurs in approximately 50% of patients with advanced melanoma.

Personal or Family History of Skin Cancer

Melanoma

Individuals who have been diagnosed with melanoma are at increased risk for a second primary melanoma. That risk may be as high as 5% and is higher in older men and in those whose first melanoma was on the upper body and face.

People with family members who have or had melanoma have approximately twice the risk of developing melanoma as those without a family history, and should be examined on a regular basis.

Nonmelanoma Skin Cancers

The evidence for an increased risk of nonmelanoma skin cancers with a family history of such cancers is increasing, but it is still weaker than the evidence for a familial connection to the risk of melanoma. The nonmelanoma skin cancers at this time are more related to sun exposure than genetics.

Skin Conditions that Increase Skin Cancer Risk

Moles (Nevi) and Other Dark Blemishes

Certain moles and dark blemishes increase the risk for skin cancer. Any mole (

nevus

) or other skin growth that seems new, changing, or unusual in any way should be evaluated by a health care professional. An existing mole can mutate and become cancerous. Although 80% of melanoma cases develop from brand new lesions or moles, your risk of developing the condition increases if you have the tendency to develop moles.Some specific moles or dark blemishes that are risk factors for melanoma include:

Freckles.

Freckles typically appear in children on sun-exposed areas and are often evenly brown or tan. They are more commonly found on people with fair skin. The more freckles a person develops as a child, the greater the risk for melanoma in adulthood. True freckles will disappear when one is not exposed to sunlight.Dysplastic (or atypical) nevi.

About 30% of the population has moles called dysplastic nevi, or atypical moles. While they are not malignant, they have an irregular appearance and can share features associated with melanoma. They may be larger than ordinary moles (most are 5 mm across, about the size of a pencil eraser, or larger), have irregular borders, and are various shades or colors. Individuals who have dysplastic nevi plus a family history of melanoma (a syndrome known as FAMM) are at a high risk of developing melanoma at an early age (younger than 40). The risk for those with atypical moles and no family history of melanoma is less clear. Anyone with atypical moles should be evaluated every 6 to 12 months by a health care professional. Visual inspection, inspection with a special light called dermoscopy, and photos may be used to evaluate the moles.Large birthmarks (giant congenital nevi).

Very large birthmarks that measure more than 8 inches (20 centimeters) across are major risk factors for melanoma. In such cases, cancer often appears by age 10 years. Medium-sized congenital nevi do not appear to increase the risk for melanoma. Whenever possible, very large birthmarks should be removed during infancy. Experts disagree about whether small birthmarks need to be removed. Parents should watch any birthmark for changes, even into adulthood.

The more moles a person has, the higher the risk that one of those moles will become cancerous, although the danger is still very small. The risk is higher with atypical moles.

Some skin growths can look like -- but are not -- melanoma. Noncancerous moles typically have the following characteristics:

- They generally remain small with clearly defined, regular borders, and uniform color. Some have a regular spotted or net-like pattern of pigmentation, however, and may even resemble early melanoma.

- They typically first appear during childhood, puberty, or young adulthood. They may naturally grow, darken, or increase in number at certain times of life, such as adolescence or pregnancy.

Examples of moles or growths that may resemble skin cancer include:

Blue Nevus

A blue nevus is a benign mole that may easily be mistaken for melanoma. It is a blue-black, smooth, raised nodule that commonly occurs on the buttocks, hands, or feet. The dark blue color results from the refraction of the light from the pigment being deeper in the skin than most brown moles.

Liver Spots

Liver spots (lentigo) are usually evenly brown or tan spots caused by the sun. They are universal signs of aging resulting from prior sun exposure. Occurring most noticeably on the hands and face, these harmless blemishes tend to enlarge and darken over time. They look like freckles but do not go away in the absence of sunlight. Despite being called liver spots, they have nothing to do with one's liver.

Spindle Cell (Spitz) Nevus

Children may develop a benign lesion called a spindle cell (or Spitz) nevus. The mole is firm, raised, and pink or reddish-brown. It may be smooth or scaly and usually appears on the face, particularly on the cheeks. It is not harmful, but it may be difficult to tell apart from a melanoma, even for experts. These are usually removed due to their similarity to melanoma and atypical features.

Diseases and Treatments that Increase Skin Cancer Risk

Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Survivors of either non-Hodgkin lymphoma or melanoma face a higher risk for other cancers. These diseases may have common causes, such as exposure to UV radiation or shared genetic factors.

Human papillomavirus (HPV)

Genital warts (caused by human papillomavirus, or HPV) may also increase the risk of squamous cell cancer in the genital and anal areas and around fingernails.

Immunosuppression

Skin cancer risk is increased in people whose immune systems are suppressed because of certain medications, organ transplantation, or medical conditions such as AIDS. Melanoma has also developed in patients who received solid organ transplants from donors who had the disease.

Immune-suppressing drugs used to treat autoimmune disorders may also increase the risk for skin cancer. For example, patients who take TNF-alpha blockers to treat rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseases carry an increased risk for both melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers. Any person on an immunosuppressive medication should have a skin check at least once per year.

Occupational Radiation and Chemical Exposure

Occupational exposure to radiation and some chemicals (vinyl chloride, polychlorinated biphenyls, and petrochemicals) in health care or industrial settings may increase the risk for melanoma. However, the evidence for this increased risk is not very strong. Airline pilots have been found to have an increased risk for melanoma. It is uncertain, however, whether this higher risk is from excessive exposure to ionizing radiation at high altitudes, or because they have more opportunity to spend time in sunny regions.

Prevention

The best way to lower your risk for skin cancer is to protect your skin from the sun and UV light. That means avoiding excess sun exposure, especially in midday when the sun is strongest.

Wear sunscreen. The use of sunscreens is complex, and everyone should understand how and when to use them. Follow instructions closely and reapply as directed after swimming or sweating. The bottom line is

not

that people should avoid sunscreens or sunblocks, but that they should always use them in combination with other sun-protective measures.Many parents are now taking effective steps to protect their children, although experts worry that they are relying too much on sunscreen and less on other protective measures.

Guidelines for Avoiding the Sun and UV Radiation

The following are some specific guidelines for avoiding excessive sun exposure:

- Properly use sunscreens that block out both UVA and UVB radiation (broad spectrum coverage) with at least SPF 30. DO NOT rely on sunscreen alone for sun protection. Also wear protective clothing and sunglasses.

- Avoid sun exposure, particularly during the hours of 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., when UV rays are the strongest.

- Use precautions, even on cloudy days. Clouds and haze do not protect you from the sun, and in some cases may intensify UVB rays.

- Avoid reflective surfaces such as water, sand, concrete, and white-painted areas.

- UV intensity depends on the

angle

of the sun, not heat or brightness. The dangers are greater closer to the start of summer. - Skin burns up to 4 times faster at higher altitudes than at sea level.

- Avoid sun lamps, tanning beds, and tanning salons. The machines use mostly high-output UVA rays.

Sun-Protective Clothing

Wear sunglasses and a hat to shield your face from the sun's rays. While regular clothing provides protection from the sun, specially-made sun protective clothing may provide even more protection. This clothing is rated using sun protection factor (SPF) or a system called the ultraviolet protection factor (UPF) index, with 50 UPF being the highest. (According to one study, this is a very reliable indicator of protection.) The clothing is expensive, however.

- Everyone, including children, should wear hats with wide brims. (Even wearing a hat, however, may not fully protect against skin cancers on the head and neck.)

- Look for loose-fitting, unbleached, tightly woven fabrics. The tighter the weave, the more protective the garment.

- Wash clothes over and over -- it improves UPF by drawing fabrics together during shrinkage. An easy way to assess protection is simply to hold the garment up to a window or lamp and see how much light comes through. The less light the better.

- Everyone over age 1 year should wear sunglasses that block all UVA and UVB rays when in the sun.

Sunscreen Guidelines

When choosing a sunscreen, look at the ingredients. Preparations that help block UV radiation are sometimes classified as sunscreens or sunblocks, according to the substances they contain. In general, sunscreens contain organic formulas and sunblocks inorganic formulas. However, the term sunblock is used less and less as sunscreens increasingly contain both kinds of ingredients:

Organic

formulas contain UV-filtering chemicals such as octocrylene, octyl salicylate, homosalate, and octyl methoxycinnamate (blocks UVB), avobenzone-Parsol 1789 (blocks UVA), cinoxate, ethylhexyl p-methoxycinnamate (blocks UVB and small amounts of UVA), oxybenzone, and benzophenone-3 (blocks UVA/UVB). Look for a wide-spectrum sunscreen that contains combinations of these ingredients and filters both UVA and UVB light. Oxybenzone may pose a risk to coral reefs and is being banned in some states.Inorganic

formulas contain the UV-blocking pigments zinc oxide or titanium dioxide. Zinc and titanium oxides lie on top of the skin and are not absorbed. They prevent nearly all UVA and UVB rays from reaching the skin. Older sunblocks were white, pasty, and unattractive, but current products use so-called microfine oxides, either zinc (Z-Cote) or titanium. They are transparent and nearly as protective as the older types.

Inexpensive products with the same ingredients work as well as expensive ones. Zinc and titanium tend to cause fewer allergic reactions so those with very sensitive skin should use the inorganic formulas.

Under FDA guidelines, only broad-spectrum sunscreens (they block UVA and UVB) that pass the FDA's broad spectrum test may be labeled "broad spectrum" and may claim to reduce the risk for skin cancer. Other non-broad-spectrum sunscreen products can only claim to help reduce sunburn.

Use of the words "waterproof," "sweatproof," and "sunblock" is no longer permitted on labels. Sunscreens may not claim to provide protection for more than 2 hours without reapplication. Sunscreens that claim water resistance must state how long protection lasts while swimming or sweating. The new sunscreen labels will also stress the importance of protective clothing for complete sun protection. Cosmetics and moisturizers that include sunscreen protection must follow the same rules.

The safety and effectiveness of combination sunscreen and insect repellent products remain unclear. While sunscreen should be reapplied frequently, insect repellent applied too often could be toxic.

Organic formulas and inorganic microfine oxides do not protect against

visible

light, which is a problem for people who have light-sensitive skin conditions, including actinic prurigo, porphyria, and chronic actinic dermatitis.Calculating SPF

SPF is a ratio based on the amount of

UVB

radiation needed to turn sunscreen- or sunblock-treated skin red compared to non-treated skin. For instance, people who sunburn in 5 minutes and who want to stay in the sun for 150 minutes might use an SPF 30 sunscreen. The formula would be: 30 (the SPF number) times 5 (minutes to burn) = 150 minutes in the sun. SPF is not measuring protection against UVA.Protection offered by sunscreens may be classified as follows:

- Minimal: SPF 2 to 11

- Moderate: SPF 12 through 29

- High: SPF 30+ to 50+

Under the new FDA guidelines, the maximum UVB protection factor has been raised from SPF 30 to 50. Since an SPF of 50 blocks approximately 98% of UVB rays, numbers higher than that are not really providing much more protection. No sunscreen can block 100% of harmful rays.

SPF Levels by Age Group

Although sunscreens are safe in most toddlers and children, they should not be the first and only lines of defense. All young children should be well-covered with clothing, sunglasses, and hats. Keep children out of the sun during peak sunlight periods. Do not use sunscreens on babies younger than 6 months without consulting a doctor.

Older children and adults (even those with darker skin) benefit from using SPFs of 15 and over. Some experts recommend that most people use SPF 30 or higher on the face and 15 or higher on the body. Adults who burn easily instead of tanning and anyone with risk factors for skin cancer should use SPF 30 or higher.

Timing and Amount of Application

Apply sunscreen or sunblock liberally as follows:

- Adults should wear sunscreen every day, even if going outdoors for only a short time. UVA is not filtered by glass so much and sun exposure occurs daily in cars.

- Apply a large amount to all exposed areas, including ears and feet. To get the level of protection indicated by the sunscreen's SPF, experts recommend half a teaspoon (2.5 mL) each for the head, neck, and each arm and a teaspoon (5 mL) each for the chest area, back, and each leg.

- For best results, apply sunscreen or sunblock 30 minutes before venturing outdoors. This allows time for the sunscreen to be absorbed. Then reapply every 2 hours while out in the sunlight.

- Also reapply each time after exercise or swimming. Choose a water-resistant or very water-resistant formula, even if your activities don't include swimming.

Possible Hazards of Relying on Sunscreens

When used generously and appropriately, sunscreen products and sun avoidance help reduce the severity of many aging skin disorders, including squamous cell carcinomas. There are certain concerns, however. Sunscreens do not appear to protect against melanoma and some basal cell carcinomas. It is also important to remember that even with the use of sunscreens, people should not stay out too long during peak sunlight hours. Even if a person doesn't sunburn, UVA rays can still penetrate the skin and do harm. In addition, some people use too little sunscreen, therefore unknowingly increasing their risk of aging skin disorders.

Chemoprevention

Chemoprevention is the use of a substance to prevent or reduce your risk for cancer. Certain drugs have been used to help block the development of skin cancers, including melanoma. These include a medicine called imiquimod, which is approved to prevent skin cancer in certain people with precancerous lesions called actinic keratosis. This medicine prompts the immune system to fight off foreign substances, including cancer cells.

Chemopreventive drugs under investigation that show promise for skin cancer include:

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, including ibuprofen and aspirin. However, there is no strong evidence for this effect, and taking these drugs specifically to prevent skin cancer is not a current recommendation.

- Retinoids, which have been shown to prevent nonmelanoma skin cancer in patients with basal cell nevus syndrome, xeroderma pigmentosum, and transplanted organs. Oral retinoids include isotretinoin and acitretin. These medications may also prevent the development of squamous cell carcinoma in patients who are taking them to treat psoriasis.

Antioxidants, Vitamins, and Herbal Products

Antioxidants are chemicals or drugs that help prevent cell damage from unstable molecules called free radicals. Antioxidants promoted to protect the skin include vitamins C and E, and coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10).

There are wide claims about the benefits of antioxidants in skin creams for wrinkles. To date, only skin products containing selenium and vitamins E and C have been shown to help reduce sun damage to the skin. However, most available brands contain very low concentrations of these antioxidants. In addition, antioxidants are not well absorbed by the skin and are quickly broken down, so the effect may be short-term. There is also no evidence that they prevent skin cancer.

Some early studies suggest that drinking coffee can reduce the risk for melanoma although it is unclear how coffee affects melanoma. More research is needed in this area.

Nicotinamide (Vitamin B3) may be effective in reducing nonmelanoma skin cancers and actinic keratosis in patients felt to be at high risk for these lesions. Further study is needed.

Warning

: A wide range of herbal products may contribute to skin problems. Some Chinese herbal creams have been found to contain corticosteroids. Mercury or arsenic contaminants have been found in some ayurvedic therapies. In addition, several oral herbal remedies used for medical or emotional conditions may produce photosensitivity (irritation in reaction to sunlight). They include, but are not limited to, St. John's wort, kava, and yohimbe. Herbal products are not tested as rigorously as prescription medicines and may have unintended and unknown side effects.Screening

Education and prevention programs have led to improved screening for skin cancer, which in turn has improved diagnosis and survival rates for melanoma. There is no standard screening schedule for the average adult who is not considered high risk. Some dermatologists or hospitals offer free screenings. Primary care physicians may do a basic assessment. Patients may ask their doctor if they should be screened by a dermatologist. High risk individuals may need a whole body scan on a set schedule. A complete skin test is recommended for anyone with a suspicious lesion.

Self-Examination for Warning Signs of Skin Cancer

Skin cancers may have many different appearances. They can be small, shiny, or waxy, scaly and rough, firm and red, crusty or bleeding, non-healing or have other features. Itching, tenderness, scaling, bleeding, crusting, or sores can signal potentially cancerous changes in any mole.

There are a number of factors to look for that are common for melanoma, which can serve as a general guide. They fall under the skin cancer ABCDE rule:

Asymmetry (A).

Skin cancers often grow in an irregular, uneven (asymmetric) way. That means one half of the abnormal skin area is different than the other half.Border (B).

Moles with jagged or blurry edges may signal that the cancer is growing and spreading.Color (C).

One of the earliest signs of melanoma may be the appearance of various colors in the mole. Because melanomas begin in pigment-forming cells, they are often multicolored lesions of tan, dark brown, or black, reflecting the production of melanin pigment at different depths in the skin. Occasionally, lesions are flesh colored or surrounded by redness or lighter areas. Pink or red areas may result from inflammation of blood vessels in the skin. Blue areas reflect pigment in the deeper layers of the skin. White areas can arise from dead cancerous tissue.Diameter (D).

A diameter of 6 millimeters or larger (about the size of a pencil eraser) is worrisome. Researchers are finding that moles greater than 6 millimeters are more likely to be melanoma. Larger moles correlate to a more invasive cancer. By the time a lesion has grown this large, there will most likely be other abnormalities. A doctor should examine any suspicious lesion, no matter what its size.Evolution (E).

A lesion that has changed in size, color, or appearance should be examined. This is the most important factor, as any change should be evaluated.

Keep in mind that the most important warning sign of melanoma is a new or changing skin lesion, regardless of its size or color. Changes that occur over a short period of time (particularly over a few weeks) are most concerning.

Experts do not agree on whether or not skin self-exams should be performed for adults without risk factors. As a result, there is no standard recommendation for how often to perform them.

However, despite a lack of clear proven benefit, anyone with risk factors for skin cancer may want to check their entire body about once a month. Risk factors include a personal or strong family history of melanoma, those with multiple nevi or atypical nevi, organ transplant recipients, and people who are very sun sensitive with a history of multiple sunburns.

It helps to draw a map of the body, indicating locations of moles, areas of discoloration, lumps, or other blemishes. Whenever you do a self-examination, compare your body to the map to check for new lesions, lumps, or moles and for changes in shape, color, and size.

There are three specific body areas to look for skin cancers, including melanomas:

- Areas visible to anyone, such as the arms or face -- about 60% of melanomas are found on these areas.

- Areas often covered with clothing and visible only to the patient or their partners -- about 34% of melanomas are found in these areas.

- Hidden areas such as the scalp, buttock folds, and mouth -- about 6% of melanomas, usually more advanced, are found here.

Ask a partner to help you check these areas. Turn on a hair dryer to separate your hair and examine the scalp.

Professional Examination for High-Risk Individuals

Those with a high risk of developing melanoma may benefit from a whole body skin exam performed by a dermatologist. People in the high-risk group include those with a personal or family history of melanoma, and individuals with multiple atypical nevi (irregular moles that are larger than normal), and those with excessive sun exposure.

Such people should protect themselves from overexposure to sunlight and have a medical examination of the entire skin surface every 3 to 12 months (the frequency depends on your risk factors). The doctor may take photographs of specific moles, or your entire body, at each visit and compare them with previous photos to look for any changes.

Examinations for Patients Previously Treated for Melanoma

People who have had melanoma and have been treated successfully are at risk for the cancer returning (recurrence) or for developing another primary melanoma. Based on recurrence rates by cancer stage, doctors suggest the following guidelines for being re-examined by a doctor after treatment:

- Stage I patients: Yearly exam

- Stage II patients: Every 6 months for the first 2 years, and annual exams afterward

- Stage III patients: Every 3 months for the first year, every 4 months for the second year, and every 6 months for years 3 to 5

All patients should be checked annually after year 5. These are guidelines only and may depend on the individual patient.

Diagnosis

An experienced doctor should first rule out noncancerous (benign) conditions that resemble melanoma, such as a mole called a melanocytic nevus.

In rare instances, a melanoma will be difficult to detect. For example, an uncommon form called a myxoid melanoma may be mistaken for a benign skin disorder known as a myxoid fibrohistiocytic lesion. Additional diagnostic procedures such as a biopsy (see below), computerized image processing, or advanced staining techniques may help to confirm or rule out the diagnosis of melanoma.

Melanoma also tends to be diagnosed at a later stage in people with darker skin.

Dermoscopy and Total Body Photography

A combination of imaging approaches should be considered for early melanoma detection and diagnosis, since each technique alone has limitations. Some doctors now use various scope-like devices (dermoscopy, dermatoscopy, or epiluminescence microscopy) that enhance the visualization of the suspected lesion. These tools are more likely to be helpful for those with atypical nevi or history of melanoma.

MelaFind is a proprietary tool used to visually detect melanoma and it was approved for use by the FDA. It uses pattern recognition of certain factors that would lead a dermatologist to more highly suspect a lesion and perform a biopsy.

Skin Biopsy

A skin biopsy is the removal of skin tissue for examination under a microscope. The exact type of biopsy depends on how deep the lesion has penetrated the skin.

Shave biopsy

uses a thin surgical blade, or scalpel, to shave off the top layers of skin. This is the most common type of biopsy used to diagnose skin cancer.Punch biopsy

uses a round, cookie-cutter-like tool. It is used to take a deeper sample of the skin. This technique shows deeper levels of skin but is often not as wide as a shave biopsy. This is more commonly used when the pathology is expected to be deeper in the skin.Incisional and excisional biopsies

remove tumors that have grown deep into the skin. An incisional biopsy cuts out part of the tumor. An excisional biopsy removes the entire tumor. These biopsies are used to diagnose melanoma.

All of the above-mentioned biopsies can be done using local anesthesia in the office setting.

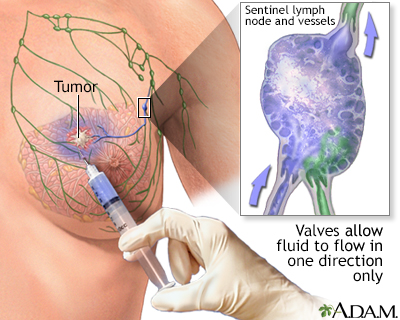

Lymph Node Biopsy

A lymph node biopsy may be needed for patients with recently diagnosed melanoma, to help determine whether the cancer has spread to one or more lymph nodes.

A procedure called sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy is now recommended for cancers that are thicker than 1 millimeter. It is usually not necessary for cancers thinner than 0.75 millimeters, unless they have opened (ulcerated). Although some evidence suggests an SLN biopsy may improve survival, no clinical trials to date have proven that it improves the outlook in people with thin melanoma.

Sentinel node biopsy is a technique that helps determine if a cancer has spread. When a cancer has been detected, often the next step is to find the lymph node closest to the tumor site and retrieve it for analysis. The concept of the "sentinel" node, or the first node to drain the area of the cancer, allows a more accurate staging of the cancer, and leaves unaffected nodes behind to continue the important job of draining fluids. The procedure involves the injection of a dye (sometimes mildly radioactive) to pinpoint the lymph node that is closest to the cancer site. Sentinel node biopsy is used to stage many kinds of cancer, including melanoma. This is reserved for deeper or more aggressive melanomas.

An SLN biopsy involves the following:

- A tiny amount of a tracer, either a radioactively labeled substance or a blue dye, is injected into the tumor site.

- The substance flows through the lymph system into the sentinel node, the first lymph node to which any cancer would spread in a given area.

- The sentinel lymph node and possibly one or two other nodes are removed and biopsied.

The results of the biopsy can help doctors decide whether or not to remove other lymph nodes:

- If the sentinel node and other nodes show signs of cancer, the nearby lymph nodes are removed.

- If they do not show signs of cancer, the rest of the lymph nodes will likely be cancer-free, and further surgery is not needed.

Secondary Tests

Patients with nonmelanoma skin cancers generally require no further workup.

Those with deep melanoma may need the following:

- Blood tests that examine levels of the enzyme lactate dehydrogenase. Elevated levels of this enzyme suggest that the cancer has spread.

- Blood tests to assess liver function and other factors, such as anemia. These tests help determine specific sites where the cancer may appear.

- Computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest, abdomen, or pelvis, which may be used to identify whether the melanoma has spread at the time of diagnosis. These scans are also used to monitor the patient after treatment.

- Positron emission tomography (PET) may also be used. PET may help find evidence that the cancer has spread elsewhere in the body. Such evidence does not always show up during a physical exam or CT scan.

Staging

Staging is the process used to determine the size of the tumor and where and how far it has spread (metastasized). Staging helps the health care team plan for appropriate treatment.

- Basal cell cancer is rarely staged, because it doesn't usually spread to other organs. However, it may be staged if it is very large.

- Squamous cell cancer of the skin may rarely be staged in people who have a high risk of the cancer spreading.

- Melanoma is always staged.

A number of factors may be used to identify melanoma that is likely to spread and may be hard to treat, including:

- The thickness, as well as how many layers of the skin the main cancer lesion has invaded.

- Whether the lesions have ulcerated.

- Primary lesions with small satellites.

- Lymph node involvement, and the number of lymph nodes involved.

- Various other factors are revealed by looking at the cancer cells under a microscope.

- Newer tests are being developed to identify certain genes associated with a more highly metastatic melanoma.

Health professionals have come up with various methods for staging cancer. This report uses the TNM staging system recommended by the American Joint Committee on Cancer.

- T = tumor. T is followed by a number (1 to 4) and a letter (a or b) to indicate tumor thickness, how "aggressive" the tumor appears under the microscope and how invasive it is locally, and the presence or absence of ulceration.

- N = node. N is followed by a number (1 to 3). If 1 node is involved, it is called N1. If 2 to 3 nodes are involved, it is called N2. If 4 or more nodes are present, it is called N3. How much cancer is present in the nodes is also important.

- M = metastasis. M is followed by a 0 (no spread) or a 1 (spread). M1 is further subdivided into a, b, or c, depending on the site of metastasis and LDH levels.

The melanoma is considered ulcerated if skin layers over the tumor appear indistinct under the microscope.

In general, the thicker the lesion and the farther the cancer has spread, the higher the stage. Survival rates decrease with increasing stage.

- The earliest melanomas, which do not penetrate beneath the surface of the skin and are known as melanoma in situ (Tis N0 M0), are highly curable and are called stage 0 or not given a stage.

- Melanomas less than 4 mm thick suggest stage I or some stage II cancers. The next step is to try to determine whether they have spread or are likely to spread to the lymph nodes.

- Melanomas that are over 4 mm thick indicate later stages. In such cases, the lymph nodes are sometimes removed in an attempt to prevent the cancer from spreading, if the tumor has not already done so.

Specific stages are as follows:

Stage I

Cure rates are excellent with surgical removal, since these cancers are least likely to have spread.

- Tumor has not spread to the lymph nodes or distant organs.

- Stage 1A. Tumor is 1 mm thick or thinner, is not ulcerated, and cell division rate is less than 1 per mm2.

- Stage IB. Tumor is 1 mm thick or thinner and is either ulcerated, or the cell division rate is at least 1 per mm2. Stage IB also includes tumors between 1.01 and 2 mm thick that are not ulcerated.

Stage II

Melanomas can be cured, but the success rate lags behind that of Stage I because a small number of undetected cancer cells may have spread to distant sites. In addition to surgery, other forms of therapy may be recommended.

- No evidence of tumor spread to the lymph nodes or distant organs.

- Stage IIA. Tumor is between 1.01 and 2 mm thick and is ulcerated, or it is 2.01 to 4 mm thick without ulceration.

- Stage IIB. Tumor is between 2.01 and 4 mm thick and is ulcerated or is greater than 4 mm thick but is not ulcerated.

- Stage IIC. Tumor is greater than 4 mm thick and is ulcerated.

Stage III

Survival rate is lower than earlier stages.

- Stage III melanoma has spread to the lymph nodes but not to the distant organs.

Stage IV

Stage IV tumors have spread under the skin or to distant organs, including distant parts of the skin. Survival rates are very low.

Treatment for Melanoma

Treatment for melanoma depends on various factors, including:

- The site of the original lesion

- The stage of the cancer

- The patient's age and general health

Treatment options include:

- Surgery to remove the tumor or tumors

- Chemotherapy

- Immunotherapy

- Radiation therapy

- Symptom relief (palliative therapy)

Surgery

Surgery is the primary treatment for all stages of melanoma. Some or all of the melanoma is often removed during the initial biopsy. After the biopsy, a surgeon will cut away additional tissue from the surrounding area to remove any stray cancer cells and have clear margins. The margin of normal skin around the melanoma is determined by the size and staging of the tumor. Sentinel lymph node biopsy is also determined by these factors.

Surgical management of melanoma that develops in rare sites, such as the vagina, cervix, and ovaries, is becoming less aggressive. Studies have shown that wide local removal works as well as radical surgery in many of these cases. Melanoma of the urethra, bladder, and ureter often requires extensive surgery, however.

Mohs Micrographic Surgery

A technique used to remove very thin layers of skin, one at a time. Each layer is examined immediately under a microscope. When the layers are shown to be cancer-free, the surgery is complete. This is usually reserved only for melanomas in areas where wide margins are not possible, such as near the eyes or ears.

The amount of tissue removed depends on the size, depth, and degree of invasion:

- Stage I lesions that are less than 1 mm thick require the smallest surgical cuts, with 1 cm around each side and down just above the muscle.

- For melanomas that are 2 mm or thicker, a margin of 2 to 3 cm is important for reducing the risk that the cancer will return.

- Thicker lesions require wider surgical cuts.

Doctors used to remove a large area, regardless of the cancer stage. This potentially disfiguring approach has been abandoned because studies have shown that removing wider margins does not improve survival. Nevertheless, sometimes skin grafts may need to be taken from other body sites to help cover the wound.

Lymph Node Removal

If there is evidence that melanoma has spread to nearby lymph nodes but has not spread beyond them, removing those lymph nodes may reduce the chance of recurrence and help patients live longer.

Surgery for Metastatic Melanoma

In some cases, surgical removal of distant tumors may be possible. This may extend survival, since often in melanoma the cancer spreads first only to a single site, such as the lung or brain.

Cryosurgery

Cryosurgery freezes skin tissue and destroys it. This procedure is not used as a primary treatment for melanomas of the skin, but it might have some value in specific situations. For example, it may be effective for smaller melanomas in the eye, a location that is difficult to treat with traditional surgery. It may be useful to eliminate cancer cells that remain after standard surgery for lentigo maligna melanomas, an unusual form of melanoma that has a wide surface and is difficult to treat.

Surgery for Lentigo Maligna

Recurrence rates are very high with lentigo maligna after conservative surgery. Although this cancer grows very slowly, lentigo maligna can develop into melanoma. Most of these lesions appear on the face and neck, where extensive surgery can be disfiguring. Patients should carefully discuss with their doctor having surgery to remove all diseased tissue while causing as little cosmetic harm as possible. Mohs surgery is a useful tool when treating lentigo maligna.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is often used to treat melanomas that return or spread. This type of therapy is not intended as a cure, but it can prolong life and improve its quality. Chemotherapy tends to work better than radiotherapy for advanced stage cancers and tumors.

Chemotherapy may also be given after surgical removal (excision) of melanoma when there is increased risk for recurrence based on size of the lesion, location, or presence of cancer cells in the local lymph nodes. This is called adjuvant chemotherapy.

Drugs Used

The following are some of the chemotherapy drugs used to treat melanoma. They may be used alone or in combination under specific situations. Chemotherapy is usually given in cycles, with rest periods between treatment periods.

- Methylating agents impair the ability of cancer cells to divide. Dacarbazine (DTIC) and temozolomide (Temodar) are the drugs most often used.

- Nitrosoureas, which include carmustine (BCNU), and lomustine (CCNU), are often used.

- Taxanes, such as docetaxel (Taxotere) and paclitaxel (Taxol), are showing some activity against melanoma.

- Biochemotherapy treatment regimens combine traditional chemotherapy agents, such as cisplatin, vinblastine, carboplatin, and dacarbazine, with biologic agents such as interferon alpha or interleukin 2. This combination may be tried for patients with large primary tumors or disease that has spread locally.

Researchers continue to investigate other chemotherapy drugs and combinations of drugs to see which ones work best.

Side Effects

Side effects occur with all chemotherapy drugs. They are more severe with higher doses and increase over the course of treatment.

Common side effects include the following:

- Anemia

- Depression

- Diarrhea

- Fatigue

- Nausea and vomiting

- Temporary hair loss

- Weight loss

- Easy bruising

Serious short- and long-term complications can also occur, and may vary depending on the specific drugs used. They include the following:

- Abnormal blood clotting (

thrombocytopenia

). - Allergic reaction.

- Increased chance for infection because the drugs suppress the immune system.

- Liver and kidney damage.

- Menstrual abnormalities and infertility in women. A natural hormone medication called a gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue, which puts women in a temporary prepubescent state during chemotherapy, may preserve fertility in some women.

- Severe drops in white blood cells (

neutropenia

). Certain chemotherapy drugs, such as taxanes, pose a higher risk for this side effect. White blood cell count may be improved by adding a drug called granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (either filgrastim or lenograstim). - Problems in concentration, motor function, and memory, which may be long-term.

- Rarely, secondary cancers such as leukemia.

- Nerve damage

Treating Side Effects

Drugs known as serotonin antagonists, especially ondansetron (Zofran) can relieve nausea and vomiting in nearly all patients given moderate drugs, and in most patients who take more powerful drugs.

Benefits of Chemotherapy

About 20% of cancers shrink in response to one or more of these drugs, but the effects last only 3 to 6 months. If the tumors completely disappear, the cancer may stay in remission much longer, but in virtually all cases it returns.

Chemotherapeutic Regional Perfusion

Chemotherapeutic regional perfusion (also called isolated limb perfusion) is a technique used to give a person very high-dose chemotherapy. It is often used effectively for melanoma that returns or spreads and that occurs on the arm or leg. It does not appear to be useful for preventing cancer spread after a first occurrence of melanoma in one of these locations.

This technique involves the following:

- The blood supply to the limb with melanoma is temporarily interrupted using a tourniquet and then rechanneled through a heart-lung machine.

- Anticancer drugs are added to the blood in up to 10 times the standard doses.

- The blood is then heated to enhance the drug's potency.

- The chemo-infused blood is sent directly to the melanoma site, minimizing the likelihood of drug toxicity. By the end of the treatment, the chemotherapy agents are completely washed away.

- Adverse effects occur in less than 1% of cases, and include severe problems in the treated limb (rarely leading to amputation) and drug leakage into the bloodstream. This can severely reduce white blood cells and lead to serious infection.

Perfusion techniques have also been tested for the pelvis, head, neck, skin of the breast, and abdomen.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy uses drugs to boost the patient's own immune system to recognize and kill the cancerous cells. Immunotherapy after surgery may help prevent recurrence in certain people with melanoma. This is called adjuvant therapy. If there is improvement in overall survival with this therapy, it is small. These medicines are often given along with chemotherapy, other immunotherapies, or both.

Immunotherapy drugs being used include:

- Interferon alpha is an FDA-approved postoperative immunotherapy for stage III melanoma. Both interferon alpha-2b and pegylated interferon alpha-2b have shown positive effects on relapse-free survival (and to a modest extent, overall survival rates for stage III melanoma). Although interferon drugs have provided some benefit, their use is controversial because of significant side effects. Additional drugs are being tested.

- Interleukin-2 is a hormone-like substance that stimulates the growth of cancer-fighting white blood cells. High-dose interleukin-2 has been shown to help patients with melanoma that has spread. The drug can cause significant side effects, including very low blood pressure, heart rhythm abnormalities, flu like symptoms, severe infections, and shortness of breath. The side effects are manageable, however, and are nearly always reversible.

Vaccine Immunotherapy

Vaccine immunotherapy is the use of a specific vaccine to treat an existing cancer. In this case, the vaccine targets one or more proteins that are produced by melanoma cells.

Vaccine immunotherapy requires the body to build up its own defenses. It can take months before benefits occur, but when they do, tumor reduction is more lasting than with chemotherapy. Vaccines also seem to have fewer side effects than interleukin and interferon.

Many therapeutic melanoma vaccines are in the advanced stages of testing, but none is approved for use in the United States at this time. So far trials have shown:

- No response at all

- The cancer completely disappearing

- Some shrinking of the melanoma

- Some slowing of the melanoma growth rate

Combined vaccine and biologic therapies are under study and show promising results.

Monoclonal Antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies work in different ways. They can attach to cancer cells, allowing your immune system to better attack the cancer cells, block the cancer cells from growing, or deliver chemotherapy or radiation to the cancer cells.

The monoclonal antibody ipilimumab (Yervoy) is approved by the FDA for use in adult patients with high-risk melanoma. This antibody allows the immune cells to attack tumors more effectively by blocking a regulator gene of the immune system. Fatigue and diarrhea are common side effects. However, the drug carries the risk of potentially fatal side effects, which include intestinal inflammation (colitis) and inflammation of the liver (hepatitis).

The monoclonal antibody pembrolizumab (Keytruda), which targets PD1, has recently been approved by FDA for treatment of melanoma that spread to lymph nodes. Another antibody targeting PD1 called nivolumab (Opdivo) is also approved for treatment of melanoma that is advanced or cannot be removed by surgery. Nivolumab is sometimes used together with ipilimumab.

- The PD1 receptor is found on certain immune system cells (known as T cells) that normally fight cancers. This receptor prevents the T cells from fighting other cells in the body.

- Anti-PD1 agents block this receptor, and as a result, the T cells are more likely to respond and fight against the cancer.

- Clinical trials of anti-PD1 monoclonal antibodies have shown them to be effective in patients with advanced, metastasized melanoma, and they seem to be less toxic than ipilimumab.

- These drugs are also being studied as adjuvant therapy to shrink tumors.

Several studies are under way to assess new monoclonal antibodies, such as KIT inhibitors, as well as to determine when, in what sequence, and which combination of these antibodies is most effective. It appears that combination treatment is the best way of using these medications.

BRAF/MEK Inhibitors

BRAF and MEK inhibitors target proteins in the BRAF mutation, which is specific for melanoma cells so that normal cells are not targeted by these medications.

Vemurafenib (Zelboraf) is an inhibitor of the mutated BRAF protein, which is found in approximately 50% of metastatic melanoma cases. Vemurafenib is approved by the FDA for treating metastatic or inoperable melanoma in patients with the BRAF mutation, and has proven superior to chemotherapy. Dabrafenib (Tafinlar), seems equally effective, but it has fewer skin side effects. Encorafenib (Braftovi) is another BRAF inhibitor. These medications shrink down tumors or slow the growth of metastatic lesions. These help prolong life but do not cure the melanoma.

Atezolizumab (Tecentriq) is a monoclonal antibody targeting mutated BRAF. It was recently approved by the FDA in combination with cobimetinib and vemurafenib for patients with metastatic or inoperable melanomas with the BRAF mutation.

Trametinib (Mekinist) is an MEK inhibitor. It targets the MEK protein found in the BRAF mutation. It was approved in 2013 for patients with BRAF mutation melanoma that cannot be surgically removed or that becomes metastatic. Other MEK inhibitors are binimetinib (Mektovi) and cobimetinib (Cotellic). These are pills taken daily.

Several combinations of BRAF and MEK inhibitors have been approved for patients with melanoma with BRAF mutation that are metastatic or that cannot be removed by surgery:

- MEK inhibitor trametinib (Mekinist) with BRAF inhibitor dabrafenib (Tafinlar)

- MEK inhibitor binimetinib (Mektovi) with BRAF inhibitor encorafenib (Braftovi)

- MEK inhibitor cobimetinib (Cotellic) with BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib (Zelboraf)

Medications that Target C-Kit

Some melanomas have mutations in the C-Kit gene that cause them to grow. This mutation is more commonly found in melanomas on the hands, feet, or inside the mouth. Imatinib (Gleevec) and nilotinib (Tasigna) are medicines that target this gene defect.

Radiation

In general, radiation is used to help relieve pain and discomfort caused by cancer that has spread or recurred. Radiation is not used as often for melanoma as it is for other forms of cancer, because melanoma cells tend to be more resistant to its effects. It may be useful in some cases.

- Radiation may help in patients who are unwilling or unable to have surgery.

- In some patients with tumors less than 3 cm deep, radiation may help slow down cancer spread when combined with a super-heating process using microwaves.

- In some high risk patients with melanoma that has spread to lymph nodes, surgery combined with regional radiation (adjuvant radiotherapy) may reduce the rate of recurrence.

- Brachytherapy, in which radioactive seeds are implanted close to the tumor, has been successfully used for melanoma of the eye.

- Lentigo maligna may sometimes be treated successfully with specific radiation treatments called soft, or Grenz, rays.

- Radiotherapy using a gamma knife (very focused gamma radiation) is also effective for cancer that has spread to the brain. In some cases it halts the cancer growth and, in rare situations, even eliminates it.

Palliative Therapy

The goal of palliative therapy is to improve the patient's quality of life and relieve symptoms. It is not a cure. Advanced melanoma that has spread to distant sites often cannot be cured, although surgery to remove tumors that have spread may provide some benefit by easing pain, increasing the general quality of life, and lengthening survival.

Patients should ask their doctors about clinical trials, studies that examine new immunotherapies (vaccines, cytokines), gene therapies, chemotherapy combinations, or other treatments.

Treatment for Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer

Many options are available for treating nonmelanoma skin cancer, including:

- Surgery

- Curettage and electrodessication

- Cryosurgery

- Photodynamic therapy (along with special cream)

- Radiation

- Topical 5-fluorouracil

- Topical immunotherapy with imiquimod

- Medications

A review of available evidence found that for Bowen disease (squamous cell carcinoma in situ), there is limited data to recommend one treatment over another. More research is needed.

Most basal and squamous cell carcinomas are treated with surgery. Research has found that surgery has the best results, but because it can have functional or cosmetic effects, some patients opt for radiation.

The first step in nonmelanoma skin cancers is to determine the risk of aggressive types of these tumors.

Squamous cell cancers of the skin are considered to be high-risk if any of the following are present:

- Recurrence at the same place where there was a previously treated squamous cell tumor

- Poorly defined borders

- Spread to the lymph nodes

- Occurrence in a patient with a suppressed immune system

- Certain features seen in microscopic examination, such as wrapping around nerves

- Poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma