Multiple sclerosis - InDepth

Highlights

What Is Multiple Sclerosis?

- Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic disease that affects the central nervous system. MS is thought to be an autoimmune disease. In MS, the body's immune system produces an inflammatory response that attacks myelin, a fatty substance that protects nerve fibers.

- The cause of MS is not known. It is not an inherited disease, but it appears that genetic factors make some people more susceptible to developing MS.

- MS affects significantly more women than men. Most people first notice symptoms between the ages of 20 to 50.

- The course of MS varies among people. The disease may be mild, moderate, or severe. Most people have the relapsing-remitting form of MS in which flare-ups (also called relapses or exacerbations) of symptoms are followed by periods of remission.

- Symptoms of MS include fatigue; vision problems; difficulty walking; muscle weakness, stiffness, and spasms; and bladder and bowel problems. Not all people have all symptoms.

Treatment

People with MS are treated with medications and rehabilitation. Several disease-modifying drugs are approved to treat MS. These drugs can help reduce the frequency and severity of relapses, and slow disease progression and disability. Drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are:

- Interferon beta-1b (Betaseron, Extavia)

- Interferon beta-1a (Avonex, Rebif, Plegridy)

- Glatiramer acetate (Copaxone)

- Natalizumab (Tysabri)

- Mitoxantrone (Novantrone)

- Fingolimod (Gilenya)

- Teriflunomide (Aubagio)

- Dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera)

- Monomethyl fumarate (Bafiertam)

- Diroximel fumarate (Vumerity)

- Ocrelizumab (Ocrevus)

- Alemtuzumab (Lemtrada)

- Ofatumumab (Kesimpta)

- Cladribine (Mavenclad)

- Ozanimod (Zeposia)

- Siponimod (Mayzent)

- Ponesimod (Ponvory)

Treatment of symptoms due to MS is also important. Various symptoms include spasticity (stiffness of muscles), muscle weakness, vision loss, pain, loss of bladder and bowel control, fatigue, depression, and others. These symptoms can exist in various combinations and each may require medications, therapy, or both.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a neurological disease that involves the central nervous system (CNS), the nerves that comprise the brain and spinal cord. The MS disease process has two main features:

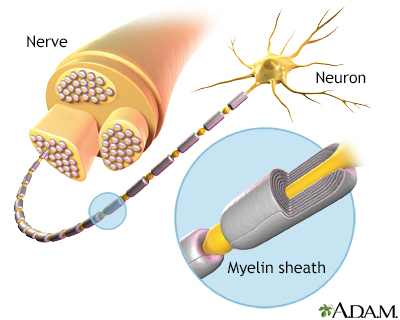

- Destruction of

myelin

, a fatty insulation covering the nerve fibers, is the main characteristic of MS. The end results of this process, calleddemyelination

, are multiple patches of hard, scarred tissue calledplaques

orlesions

. Sclerosis comes from the Greek word skleros, which means hard. - Damage of axons, the fibers that carry electric impulses away from a nerve cell, is also a major factor in the permanent disability that occurs with MS.

Myelin is the layer that forms around nerves. Its purpose is to speed the transmission of impulses along nerve cells.

The symptoms, severity, and course of MS vary widely depending partly on the sites of the plaques and the extent of the demyelination.

Autoimmune Disease Process

MS is thought to be an autoimmune disorder. In autoimmune diseases, immune factors attack the body's own cells. In the case of MS, the immune system attacks the tissues that make up myelin. The damage to myelin, and nerve fibers (axons), is caused by over-active T cells. T cells are a type of white blood cell called lymphocytes.

Types of Multiple Sclerosis

Doctors generally group multiple sclerosis into four major disease course categories:

Relapsing-Remitting MS.

Relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) is the most common form of MS. About 85% of patients are first diagnosed with this type of MS. RRMS is marked by flare-ups (also called relapses or exacerbations) of symptoms followed by periods of remission when symptoms improve or disappear.Secondary-Progressive MS.

Some people with RRMS go on to develop secondary-progressive MS (SPMS). (For many people, treatment with disease-modifying medications helps delay this progression.) In SPMS, the disease course continues to worsen with or without periods of remission or leveling off of symptom severity (plateaus).Primary-Progressive MS.

About 10% of people are diagnosed with primary-progressive MS (PPMS). In PPMS, symptoms continue to worsen gradually from the very beginning. PPMS has no relapses or remissions. There may be periods of occasional plateaus. This type of MS is more resistant to the medications typically used to treat the illness.Progressive-Relapsing MS.

Progressive-relapsing MS (PRMS) is a rare form of MS, occurring in less than 5% of people. It is progressive from the start with intermittent flare-ups of worsening symptoms along the way. There are no periods of remission.

Causes

As with other autoimmune disorders, the exact cause of MS is unknown. A combination of environmental and genetic factors likely plays a role.

Genetic Factors

Multiple sclerosis is not hereditary, but genetic factors appear to make some people more susceptible to the disease. The risk of MS is determined by the interactions of dozens of genes. The most significant genetic link to MS occurs in the major histocompatibility complex (MHC), a cluster of genes on chromosome 6 that are essential for immune system function. A much smaller percentage of MS cases may be due to variations in interleukin-7 (IL-7) and interleukin-2 (IL-2) gene receptors, which are also related to immune system regulation.

Environmental Factors

Multiple sclerosis is more common in certain geographical areas of the world, particularly areas that are farther from the equator. Prevalence is generally highest in northern European and North American countries. The clustering of MS cases in these regions has led researchers to investigate whether certain toxins, infections, or vitamin deficiencies (such as vitamin D) may play a factor in triggering MS in genetically susceptible people.

Infectious organisms, mainly viruses, have long been suspects. They include Epstein-Barr virus (the cause of mononucleosis), herpesvirus 6, herpes simplex virus, influenza, measles, mumps, varicella-zoster virus, cytomegalovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, canine distemper virus, and Chlamydia pneumoniae. However, no direct link has been proven between these infections and multiple sclerosis. There is no evidence that any type of vaccination causes multiple sclerosis.

Risk Factors

Age

MS usually first appears between the ages of 20 and 50, with an average age of about 30. It rarely develops before age 15 or after age 60.

Sex

MS is about 2.5 times more common among women than men. The sex difference in MS prevalence is largest among people who develop MS at a younger age. However, some research indicates that men may be more disabled by the disease than women.

Race and Ethnicity

Multiple sclerosis occurs worldwide but is most common in white people of northern European origin, mostly those of Scottish descent.

Family History

A family history of the disease may put some people at risk for MS, although the risk for someone inheriting all the genetic factors associated with MS is only about 2% to 4%. An identical twin of a person with MS has about a 25% chance of also developing MS. Some research indicates that family members who have MS tend to develop the disease at around the same age. However, family history does not predict whether one family member will experience the same disease severity as another family member.

Vitamin D Deficiency

Research suggests that low blood levels of vitamin D may increase the risk for developing MS, and for worsening the course of the disease in its early stages. Currently, there is no evidence that Vitamin D therapy is beneficial for MS, although additional studies are underway.

Vitamin D deficiency may partially explain why MS is less common in equatorial regions. People who live near the equator have an abundance of sun exposure and do not generally have vitamin D deficiency.

Possible Protective Factors

Estrogen and Oral Contraceptives

Higher estrogen levels may temporarily lower the risk of developing MS. Studies indicate that oral contraceptives (which contain estrogen) and pregnancy delay the onset of MS. The risk for a first clinical attack increases, however, in the first 6 months after a woman gives birth.

Prognosis

Multiple sclerosis is not a fatal disease. Except in rare cases of severe disease, most people with MS have a normal or near-normal life span and often die from the same conditions (heart disease or cancer, for example) that affect the general population. Still, MS symptoms can negatively affect quality of life. Suicide rates among people with MS are higher than average.

The majority of people with MS do not become severely disabled. Twenty years after diagnosis, about two thirds of people with MS remain ambulatory and do not need a wheelchair, although many of them may use a cane or crutches for walking assistance. Some people use an electric scooter or wheelchair to help cope with fatigue or balance problems.

The severity of the disease, and disease progression, varies widely from person to person and is unpredictable. About 20% of people remain asymptomatic or become only mildly symptomatic after an initial clinical event. Another 20% experience a rapidly progressive condition. Most people with MS will have some degree of disease progression. Women tend to have a better outlook than men.

Factors that determine a higher risk for a severe condition include:

- Age over 40 years at the time of onset of symptoms

- Initial symptoms that affect motor control, mental functioning, or urinary control

- Initial symptoms that affect multiple regions of the body

- Attacks in the first years that are frequent, or a short time between the first two attacks

- Incomplete remissions

- Rapid progression to disability

- MS that is progressive from the beginning or becomes progressive shortly after the onset

Symptoms

Symptoms of multiple sclerosis (MS) appear in a variety of ways. Most people first have a single attack of symptoms, a neurological episode called a

clinically isolated syndrome

(CIS), which typically occurs between the ages of 20 and 50. Initial symptoms may be mild enough that people do not always seek medical care.If a second attack occurs, the person is considered to have relapsing-remitting MS. Much less commonly, the disease is progressive from the start, with more or less continuous symptoms. This is called primary progressive MS.

Symptoms in MS depend on the location of the nerve lesions. Not all symptoms affect all people.

Early Symptoms

Symptoms more likely to occur earlier in the disease include:

Vision Problems.

Optic neuritis, inflammation of the nerves in the eye, is a common early symptom. People may initially experience blurred or double vision, often because of problems with one eye. Most people usually have good recovery from the first attack. However, with recurrent attacks and as the condition progresses, vision loss increases, although total blindness is rare.Tingling and Numbness Sensations.

Tingling, crawling or burning sensations (paresthesia), or loss of sensation, can occur. There may be sensations of intense heat or cold. Symptoms often begin at the end of the legs or arms and move up towards the beginning of the limb. Lhermitte sign, which is caused by lesions in the spinal cord in the neck, is an electrical buzzing sensation that runs down the back and into the legs. It occurs when bending the neck forward.Muscle Weakness and Spasms.

People may feel weakness, clumsiness, or heaviness in the limbs. They may have difficulty with finger dexterity. Muscle spasms and stiffness (spasticity), particularly in the legs, occur in an initial attack of MS in nearly half of people.Problems with Balance and Coordination.

People may have difficulty walking normally and keeping their balance due to unsteady gait. They may have trouble grasping small objects. These problems can be worsened by other common MS symptoms, such as dizziness and tremor. Ataxia (lack of muscle coordination) and tremors (shaking or trembling of limb) are also common.Fatigue.

Fatigue is the most common and debilitating symptom of MS and often occurs early in the disease. Fatigue is typically worse in the late afternoon and improves in the early evening.

Other Common Symptoms

Other common symptoms that progress over time include:

Bladder and Bowel Problems

Some people have problems emptying their bladder (urinary retention) and bowels (constipation) or find they cannot control their bladder and bowels (incontinence). People with urge incontinence need to urinate frequently or are unable to reach the bathroom before leakage occurs. Bladder problems, and catheterization for urinary retention, can lead to urinary tract infections.

Pain

Most people with MS have pain at some point during the course of the disease, and many are never completely pain free. MS causes many pain syndromes, which can last a short time or a long time. Some types of pain worsen with age and disease progression. Pain syndromes associated with MS include trigeminal neuralgia (facial pain), powerful spasms and cramps, pressure pain, stiffened joints, and a variety of sensations, including feelings of itching, burning, and shooting pain.

Sexual Dysfunction

Sexual dysfunction is a common problem. Men are likely to have erectile dysfunction, and women often have problems with vaginal lubrication. Sexual dysfunction appears to be highly associated with urinary dysfunction.

Speech and Swallowing Problems

Up to half of people with MS have trouble chewing or swallowing. Some people have slurred speech and problems speaking clearly.

Thinking, Concentration, and Memory Problems

Cognitive problems, such as having trouble concentrating, reasoning, and solving problems, affect many people with MS. Memory problems are common. These disabilities can create difficulties in the workplace.

Emotional and Psychiatric Problems

Depression is very common and is sometimes very severe. Depression can be caused both by lesions and physical changes in the brain as well as emotional response to the stress of dealing with MS. People with MS are also at risk for anxiety, bipolar, and psychotic disorders. Some people with severe MS have uncontrolled and extreme mood swings where they alternate between uncontrollable laughing and weeping (pseudobulbar affect).

Possible Symptom Triggers

MS flares (relapses) can be triggered by certain factors. Possible symptom triggers include:

Infections.

Viral and bacterial infections, including urinary tract infections, may provoke MS symptoms.Heat and Cold.

Sudden changes in temperature or humidity can trigger symptoms. Many people with MS have heat intolerance and find that heat worsens their symptoms.Stress.

Emotional and physical stress may worsen MS symptoms.

Diagnosis

Most people with MS first seek medical help after an initial attack of symptoms, called a clinically isolated syndrome (CIS). Not all people who have a CIS go on to develop MS, although MRI is very helpful in predicting who is at high risk.

MS can be challenging to diagnose as there is no single test for it, and a number of other conditions may mimic its symptoms. To confirm a diagnosis of MS the doctor needs to find:

- Evidence of nerve damage in at least two different areas of the central nervous system (brain, spinal cord, and optic nerves)

- Evidence that the damage occurred in episodes that happened at least one month apart

- No evidence that the damage is caused by other conditions

A diagnosis of MS is based on results from a combination of various tests. They include medical history, neurological exam, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, and possibly evoked potential tests or a spinal fluid test.

Medical History

The doctor will ask about your personal and family medical history, including lifestyle factors, prescription or other drug use, and other medical conditions that you or your relatives may have had. The doctor will ask you to describe your symptoms, when they occurred, and how long they lasted.

Neurological Exam

In a neurological exam, the doctor will test your vision and reflexes and evaluate balance, coordination, and muscle strength.

Evoked Potential (EP) Tests

The evoked potential (EP) test is a simple and painless electrical test of nerve function that assesses how long it takes nerve impulses from the eye, ear, or skin to reach the brain. It involves having electrodes placed on the scalp over specific areas of the brain that process sensory information. EP tests can be used to evaluate nerve transmission for vision, sound, or muscle responses in the legs or arms.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans are important diagnostic tools in MS and are used for diagnosing multiple sclerosis, tracking changes over time, and helping to determine treatment effectiveness.

MRI scans can detect bright patches that indicate areas of damaged myelin and injured tissue (lesions) caused by MS. However, about 5% of people who are confirmed to have MS based on other diagnostic criteria, do not show evidence of lesions in an initial MRI.

Once diagnosed, periodic follow-up MRIs can be used to track the disease and effectiveness of treatments in two ways:

- By distinguishing new lesions from old ones

- Revealing increasing or decreasing numbers of lesions within the central nervous system over time

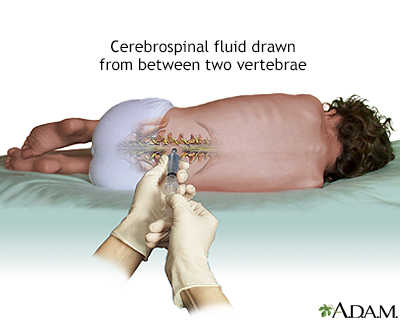

Cerebrospinal Fluid Analysis

A spinal fluid test cannot by itself confirm or exclude multiple sclerosis but it can be useful when combined with other tests. Obtaining a sample of spinal fluid requires a lumbar puncture (also called spinal tap).

Spinal fluid in people with MS often contains unusually high levels of immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies as well as other proteins and fragments of myelin. These can be signs of an autoimmune disorder, but not necessarily MS. About 90% of people with MS will have several types of these proteins (oligoclonal bands) in the spinal fluid, but not in the blood.

A lumbar puncture, or spinal tap, is a procedure to collect cerebrospinal fluid to check for the presence of disease or injury. A spinal needle is inserted, often between the 3rd and 4th lumbar vertebrae in the lower spine. Once the needle is properly positioned in the subarachnoid space (the space between the spinal cord and its covering, the meninges), pressures can be measured and fluid can be collected for testing.

Ruling Out Other Disorders

The symptoms of MS overlap with a number of other diseases that must be ruled out. These conditions include stroke, alcoholism, emotional disorders, Lyme disease, chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, AIDS, cervical spondylosis, other neurologic degenerative illnesses, transverse myelitis, and certain other autoimmune disorders (sarcoidosis, hypothyroidism, scleroderma, Sjögren syndrome, vasculitis, and systemic lupus erythematosus).

Treatment

The goals of treatment for MS are to:

- Modify the disease course by reducing the number and severity of relapses (also called exacerbations or flares), reducing accumulation of lesions, and slowing the progression of disability

- Treat relapses on a short-term as-needed basis

- Manage symptoms

It is best to seek care from a neurologist experienced in treating MS.

Early Treatment

Evidence strongly suggests that the most destructive changes in the brain occur very early on in the MS disease process -- and may cause considerable damage even before symptoms begin.

Many doctors recommend treatment after a first neurological episode of MS (a clinically isolated syndrome) using disease-modifying drugs. The best current approach is to use specific findings from MRI scans to determine people at highest risk for progression, making them likely candidates for early treatment with these drugs.

Over a third of people will progress even with immediate treatment, but without early treatment about half of patients with clinically isolated syndrome will progress to clinically identifiable MS.

The treatment of progressive MS is more problematic. For the most part, disease modifying drugs have failed to have a significant effect on slowing the disease process.

Treatment with Disease-Modifying Drugs

The following disease-modifying drugs are approved by the FDA for treatment of MS and may be recommended, depending on clinical presentation:

- Interferon beta-1b (Betaseron, Extavia). Given in subcutaneous (under the skin) injections every other day.

- Interferon beta-1a (Avonex). Given as weekly intramuscular injections.

- Interferon beta-1a (Rebif). Given as subcutaneous injection 3 times a week.

- Interferon beta-1a (Plegridy). Given as subcutaneous injection once every 2 weeks.

- Glatiramer acetate (Copaxone, Glatopa). Given once daily (20 mg/mL), or 3 times a week (40 mg/mL), by subcutaneous injection.

- Natalizumab (Tysabri). Given by intravenous infusion once every 4 weeks.

- Mitoxantrone (Novantrone). Given intravenously once every 3 months for 2 to 3 years at most.

- Fingolimod (Gilenya). Taken daily as a pill.

- Teriflunomide (Aubagio). Taken daily as a pill.

- Dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera). Taken twice daily as a pill.

- Monomethyl fumarate (Bafiertam). Taken twice daily as a pill.

- Diroximel fumarate (Vumerity). Taken twice daily as a pill.

- Ocrelizumab (Ocrevus). Given by intravenous infusion once every 6 months.

- Alemtuzumab (Lemtrada). Given by intravenous infusion once yearly.

- Ofatumumab (Kesimpta). Given by monthly injection.

- Cladribine (Mavenclad). Taken as pills in two week-long yearly treatment courses.

- Ozanimod (Zeposia). Taken daily as a pill.

- Siponimod (Mayzent). Taken daily as a pill.

- Ponesimod (Ponvory). Taken daily as a pill.

The interferon drugs (Betaseron, Extavia, Avonex, Rebif, and Plegridy) and glatiramer acetate (Copaxone) are given by self-injection at home. Natalizumab (Tysabri), alemtuzumab (Lemtrada), ocrelizumab (Ocrevus), and mitoxantrone (Novantrone) are given by intravenous infusion in a hospital or medical clinic setting. Fingolimod (Gilenya), teriflunomide (Aubagio), and dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera) are taken by mouth as pills.

Most of these drugs are taken on a long-term basis. They can help reduce disease activity and progression for relapse-remitting MS (the most common form of MS) and other types of MS that have relapses (secondary-progressive MS, progressive-relapsing MS). Disease-modifying drugs can have significant side effects. Before choosing when to start treatment or which treatment to use, the clinician should inform the patient of:

- Potential risks and benefits

- The importance of treatment adherence

- How to monitor symptoms

If disease-modifying drugs do not work or if they are not accessible, doctors may try other drugs that are not specifically approved for MS. They include intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg), methotrexate, azathioprine (Imuran), cladribine (Leustatin) and cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan).

Treating Acute Relapses

A relapse (also called exacerbation or flare-up) is an attack that brings about new symptoms or worsening of old symptoms. It is caused by inflammation in the central nervous system. Relapses can be mild or severe. They may last from a few days to several months.

Pseudoexacerbations are temporary worsening of symptoms that are usually caused by an external trigger, such as infection, heat, or stress. Pseudoexacerbations do not involve myelin inflammation and symptoms often subside within 24 hours. To be considered a true relapse or exacerbation, symptoms and neurological signs must last at least 24 hours and occur at least 30 days after a previous attack.

Not all acute relapses require treatment. For attacks that are severe, a short course of high-dose corticosteroid drugs is the standard treatment. Typically, intravenous methylprednisolone (IVMP) is given for 3 to 5 days. Sometimes this is followed by oral prednisolone for a few days. Long-term treatment with corticosteroids is not recommended. These drugs can cause serious side effects and do not have any effect on MS disease progression.

Other treatment options for relapses are injections of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and plasmapheresis (plasma exchange). These treatments are usually reserved for a small percentage of people with very severe symptoms who do not respond to steroid drugs.

Treating Symptoms

MS symptoms are managed through a combination of treatment approaches that include medications, self-care, and physical and occupational therapy.

Drugs that are specifically approved for treating symptoms associated with MS include:

- Dalfampridine (Ampyra) is approved to improve walking in people with spasticity from MS. In clinical trials, people treated with dalfampridine had faster walking speeds than those who received a placebo. Dalfampridine is taken as a pill. The drug may cause seizures.

- OnabotulinumtoxinA (Botox) is approved to treat upper limb spasticity in the flexor muscles of the elbow, wrist, and fingers. It is also approved to treat urinary incontinence associated with certain neurological conditions, including multiple sclerosis. Botox is given by injection by a health care provider into affected muscles.

- Baclofen (Lioresal, Gablofen, generic) is approved to treat severe spasticity. It is given orally in pill form, and for severe spasticity it can be injected intrathecally (into the spinal fluid canal, to reach cerebrospinal fluid or CFS) through a surgically implanted pump.

- A combination pill of dextromethorphan and quinidine (Nuedexta ) is approved for treating pseudobulbar affect, a condition characterized by sudden outbursts of involuntary laughing or crying.

Investigational Treatments

New Medications

New types of injectable and oral drugs for MS are currently being investigated in clinical trials.

Estriol

The use of estriol as an adjunct treatment has been evaluated and shown potential value in reducing relapse rates. Further investigation is needed.

Stem Cell Transplantation

Investigators are studying the possible benefits of stem cell transplantation procedures. Stem cells are produced in the bone marrow and are the early forms for all blood cells in the body (including red, white, and immune cells). Early studies indicate that stem cell transplantation may slow MS progression. Larger randomized controlled trials are currently under way.

Unproven Treatments

People with MS should be highly skeptical about treatments touted for MS that are unproven, have not been rigorously investigated, and have scant scientific evidence for safety or efficacy. For example, the FDA has warned of injuries and deaths associated with "liberation therapy." This surgical procedure uses balloon angioplasty devices or stents to widen veins in the chest and neck associated with chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency (CCSVI).

The procedure has caused stroke, nerve damage, and death in several people. A research trial found the procedure did not help any study participants and worsened symptoms in several people. Studies have proven that CCSVI does not cause MS, and is not common in people with MS.

Medications

Interferon Beta Drugs

Interferons (so-called because they "interfere" with viral replication) suppress inflammatory factors in the immune system that are associated with the attack on myelin. Interferon drugs are the main treatments for relapsing-remitting MS. Doctors recommend that these medications be used early in the course of the disease and continued indefinitely, unless they produce no benefits or have severe side effects. When the drug is discontinued, disease activity may increase.

Brands

Interferon drugs used for MS are interferon beta-1b (Betaseron, Extavia) and interferon beta-1a (Avonex, Rebif, and Plegridy). They are the same chemical, but Avonex is given as weekly intramuscular injection, Rebif is injected subcutaneously (under the skin) 3 times a week, and Plegridy is injected subcutaneously once every 14 days.

Side Effects

Side effects include:

- Flu-like symptoms. Flu-like symptoms (fever, chills, sweating, muscle aches, and fatigue) following injection are a common complaint. These symptoms usually lessen over time. Taking acetaminophen (Tylenol, generic) before the injection can help.

- Injection site reactions. Pain, redness, and swelling can occur at the injection site. Applying ice or a cool compress to the skin a few minutes before injection can help prevent pain.

- Less common side effects include allergic reactions, depression, mild anemia, low white blood cell counts, and liver abnormalities. People who take interferon drugs should have a baseline liver function test at the start of treatment and receive periodic testing afterwards. They should avoid alcohol.

Neutralizing Antibodies That Reduce Effectiveness

Over time, people taking interferons develop antibodies to the drugs, some of which can neutralize their effects. The risk for neutralizing antibodies (NAbs) increases with higher doses and greater frequency of use. Interferons injected under the skin (Betaseron, Rebif) are more likely to produce neutralizing antibodies than Avonex, which is injected into a muscle.

People who have this reaction may be treated with an alternative interferon or with glatiramer, which has an extremely low risk, for NAbs. Often after switching drugs, NAb levels decline, and the patient may be able to return to the original interferon.

Glatiramer Acetate (Copaxone)

Glatiramer acetate (Copaxone) is a synthetic molecule that resembles a basic protein found in myelin. It is not known exactly how this medication works in treating MS. It may act as a decoy to trick white blood cells into attacking it instead of myelin. It may also affect the proportions of immune cells that promote or inhibit inflammation. Glatiramer acetate is approved to help reduce the frequency of relapses in people with relapsing-remitting MS. It comes in pre-filled syringes and is given by subcutaneous (under the skin) injections.

The best results are for people in early stages of MS, but the longer the drug is used, the greater the improvement. Benefits may last for years. Glatiramer acetate appears to work as well as interferon beta drugs in decreasing the number and severity of relapses, but it may have less effect on lesions.

Side Effects

Side effects may occur right after the injection. They include pain at the injection site, chest pain, rapid heartbeat, flushing, anxiety, and shortness of breath.

Natalizumab (Tysabri) and Other Monoclonal Antibodies

Natalizumab (Tysabri) is a monoclonal antibody drug approved for treatment of MS. Monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) are immune proteins that have specific targets, including viruses, proteins, different cells and even other antibodies. Natalizumab targets a protein on white blood cells and may prevent them from attacking myelin.

Because of rare, but potentially serious side effects, natalizumab is often only given to people who have not responded to or who cannot tolerate other disease-modifying drugs, or to people who have a particularly aggressive course of MS. Natalizumab can only be taken alone, not in combination with other immune-modifying drugs. The drug is given by IV infusion once every 4 weeks.

Many people who take natalizumab report great improvement in reduction of MS relapses and the drug appears to work well in slowing disease progression. However, natalizumab does carry risks for potentially serious side effects.

Common Side Effects

Common side effects include headache, fatigue, depression, joint pain, abdominal and chest discomfort, along with urinary tract, pneumonia, and other infections.

Severe Side Effects

People who take natalizumab must be monitored for signs of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML). PML is a rare neurological disease that is often fatal and can affect people with compromised immune systems.

Three factors increase the risk for PML:

- The presence of anti-JCV antibodies. The John Cunningham (JC) virus is a common and normally harmless virus. However, in people with weakened immune systems, the JC virus can cause PML. PML only occurs in people who have been exposed to the JC virus. Your health care provider can use the Stratify JCV Antibody ELISA blood test to determine if you have JC virus antibodies (a sign of exposure). If you test negative, you should continue to be tested regularly while taking natalizumab. If you test positive, discuss with your doctor your risks of developing PML while on natalizumab.

- Longer duration of natalizumab treatment. The risk for PML appears to increase when people receive more than 24 natalizumab infusions (2 years of treatment).

- Prior treatment with an immunosuppressant drug (such as mitoxantrone, azathioprine, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, or mycophenolate) increases the risk for PML.

Symptoms of PML may include progressive weakness on one side of the body, clumsiness of limbs, vision disturbances, and changes in thinking, memory, and orientation that may result in confusion or personality changes. If PML is suspected, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan can confirm early stages of the disease. An MRI brain scan prior to starting natalizumab treatment can evaluate pre-existing brain lesions.

Natalizumab may cause liver damage. Signs of liver injury include yellowing of skin and eyes (jaundice), sudden darkening of urine, fatigue, and nausea and vomiting. You should immediately contact your doctor if any of these symptoms develop. If blood tests confirm liver injury, natalizumab should be discontinued.

Other monoclonal antibodies targeting proteins on the surface of leukocytes (white blood cells) have been approved for use in MS:

- Ocrelizumab is a monoclonal antibody approved by the FDA for treatment of primary progressive and relapsing remitting MS. This drug is currently the only one shown to alter disease worsening in people with primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS) who are able to walk.

- Alemtuzumab (Lemtrada) is a monoclonal antibody approved by the FDA for treatment of patients with relapsing forms of MS. Alemtuzumab is recommended for patients with highly active MS. It may have serious adverse effects including potentially fatal autoimmune problems.

- Zinbryta (daclizumab), FDA-approved for the treatment of adults, has been withdrawn due to reports of severe liver damage and immune-related conditions.

- Ofatumumab is a monoclonal antibody approved by the FDA for treatment of patients with relapsing forms of MS. It should not be taken by patients with hepatitis B. It can also increase risk of PML.

Mitoxantrone (Novantrone)

Mitoxantrone (Novantrone) was the first drug approved specifically for secondary-progressive MS and progressive-relapsing MS. It is also used to treat worsening relapsing-remitting MS. Mitoxantrone is often used in combination with an interferon beta drug or glatiramer acetate.

Cumulative doses can have toxic effects on the heart, including heart failure, so the drug is only used for a limited period of 2 to 3 years. You should get a heart evaluation, including evaluation of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), before starting this drug and before each dose administration. Mitoxantrone is associated with infertility and can also increase the risk for leukemia. Because several other treatments for MS which are safer are now available, mitoxantrone is rarely used these days.

Side Effects

In addition to risks of heart damage, common side effects of mitoxantrone include nausea, thinning hair, bladder infections, mouth sores, and loss of menstrual periods. This drug may cause a temporary bluish color to urine or eyes during the first 24 hours after IV infusion.

Fingolimod (Gilenya)

Fingolimod (Gilenya) was the first oral drug approved to treat relapsing forms of MS. (The other two oral drugs are teriflunomide [Aubagio] and dimethyl fumarate [Tecfidera].) Fingolimod is taken once-daily as a pill. Fingolimod is recommended in patients with highly active MS.

Common Side Effects

Common side effects may include headache, influenza, diarrhea, back pain, cough, and abnormal liver enzymes.

Severe Side Effects

Fingolimod can decrease heart rate (bradycardia, or bradyarrhythmia) especially after the first dose. (The provider should monitor the patient for 6 hours after the first dose to make sure there are no heart problems.) Heart rates usually stabilize within a month after starting fingolimod. Because of these cardiac side effects, people with certain pre-existing heart conditions or recent history of heart attack or stroke should not use fingolimod.

Other serious side effects include macular edema (fluid accumulation in a part of the eye's retina), increased risk of serious infections, and shortness of breath. Fingolimod can cause liver problems so people should get liver tests before starting the drug. This drug may cause birth defects. Women of childbearing age who take fingolimod should use birth control while on the drug.

Teriflunomide (Aubagio)

Teriflunomide (Aubagio) was the second approved oral treatment for relapsing forms of MS. Like fingolimod, teriflunomide is taken as a once-daily pill.

Common Side Effects

Teriflunomide may cause diarrhea, upset stomach, flu-like symptoms, and a burning sensation in skin. Hair thinning and loss may occur.

Severe Side Effects

Teriflunomide can cause serious liver problems and should not be taken by people with liver disease. The drug can lower white blood cell counts, which increases the risk for infections. Teriflunomide can affect a man's sperm and it can cause birth defects in pregnant women. Both men and women who take teriflunomide should use contraceptives while taking this drug.

Dimethyl Fumarate (Tecfidera)

Dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera) is the newest of the three oral drugs approved for treating relapsing forms of MS. Dimethyl fumarate is taken twice daily as a pill.

Common Side Effects

Like fingolimod and teriflunomide, this drug can cause upset stomach and diarrhea. This drug may also cause skin flushing and stomach pain.

Severe Side Effects

Dimethyl fumarate may lower white blood cell counts although it does not appear to seriously increase the risk for infections. It is uncertain if dimethyl fumarate causes birth defects or can be passed along in breast milk. This drug was approved in 2013, so its side effects may not yet be fully known.

Monomethyl fumarate and diroximel fumarate are similar to dimethyl fumarate.

Lifestyle Changes

Living with multiple sclerosis (MS) can be a challenging and frustrating experience. Fortunately, there are many different types of lifestyle changes and strategies that can help you better manage the symptoms and stresses of this disorder.

Rehabilitation Therapies

People with MS can benefit from various rehabilitation services to help them cope with physical and emotional symptoms:

Physical Therapy.

Physical therapists provide professional guidance on exercise programs. They can also advise on how to best use mobility aids (such as canes, crutches, and scooters) and other assistive devices.Occupational Therapy.

Occupational therapists help people learn how to improve their functioning and independence within their home and workplace environments. They can provide professional advice on what sort of adaptive tools, such as grab bars, should be used in the bathroom, bedroom, and kitchen.Vocational Therapy.

Vocational therapists provide guidance on how to best manage in the workplace.Speech/Language Therapy.

Speech and language therapists treat problems with speech and communication. They can also help address problems with swallowing.Psychological Therapies.

Psychotherapy can help patients and their families cope with the emotional aspects of living with MS. Some people with MS may benefit from cognitive-behavioral therapy to help develop techniques for dealing with and overcoming negative thought patterns.

Assistive Devices and Adaptive Tools

In addition to electric scooters and other mobility devices, there are many devices that can make life easier in the home. They include:

- Kitchen gadgets, such as jar openers, assist with gripping and grabbing. Special kitchen tools, like rocker knives, can make cooking chores easier. Lower countertops and pull-out shelves are also helpful. Reaching devices can help retrieve various objects.

- Door-knob extenders and key turners are helpful for people who have trouble turning their wrists.

- Shower benches, grip bars, and raised toilet seats can make bathrooms safer and easier to use independently.

- Changes in the home environment are important. Place items within easy reach. Remove clutter so you can find things easier and remove loose rugs to avoid the risk for falls. Rearrange furniture so you can walk without obstruction. If you get fatigued easily, try placing extra chairs in certain spots so you can take a break while going through your daily routines.

Conserving Energy

Fatigue is very common in multiple sclerosis and it can worsen as the day progresses. It is important to get sufficient rest and to develop strategies (and priorities) for conserving energy. An occupational or physical therapist can advise you on ways to make walking and daily household tasks less tiring. Assistive devices can be very helpful. If you have problems with sleep, or bladder problems are interfering with your sleep, talk with your doctor about possible medications or other therapies.

Body Temperature Control

Raised body temperature often triggers symptoms of MS. The following measures may help:

- Stay hydrated. Drink plenty of fluids, but avoid caffeinated beverages. Caffeine acts as a diuretic.

- Use air conditioners in the summer and keep the home slightly cool in the winter. Misting fans can also help lower air temperature.

- Exercise in cool water and avoid overheated pools.

- Cooling vests can be helpful. Newer styles of vests are lightweight and contain special fabrics, chemicals, or gels that help reduce body temperature. There are also special cooling scarves, bandanas, and hats.

Exercise

People with MS should try to engage in a variety of exercises including stretching, muscle strengthening, and range-of-motion. Exercise can help reduce fatigue and relieve muscle spasticity, and it can help your mind and spirit as well as your body. In people with MS, exercise increases walking speed, balance, and endurance, and improves cognition and depressive symptoms. A physical therapist can suggest exercise programs that are best for you, and help set realistic goals.

Many people with MS find water a great environment for exercise. In addition to swimming, there are various types of aquatic exercises that can help improve balance, strength, and stretching. People with MS should take caution with exercises that raise body temperature, which can temporarily worsen symptoms.

Nutrition

A healthy diet is very important for keeping your heart, bones, and immune system strong. Eating right will also help control your weight (a concern for many patients with MS) and help with fatigue. Some dietary suggestions include:

- Drink about 6 to 8 glasses of water a day. Drinking water helps prevent constipation and urinary tract infections. Avoid caffeinated or alcoholic beverages, which can irritate the bladder and worsen urinary incontinence. Avoid sugary drinks, which contain only extra calories and no nutritional value.

- Eat a diet rich in fiber, particularly from whole grains (especially bran, oats, or flax), fruits (particularly prunes), and vegetables. High-fiber diets are important for preventing constipation.

- Consider low-fat diets. They are not proven to have much effect on MS but are, in any case, generally healthy.

- Include in your diet omega-3 fatty acids, which are found in oily fish and fish oil supplements. These healthy types of fats may possibly help reduce inflammation and improve symptoms. The best results come from eating fatty fish (salmon, tuna, sardines, and mackerel). Supplement forms of omega-3 fatty acids do not appear to be effective for MS. If you take fish oil supplements (or any kind of supplement) be sure to let your provider know in case there is a risk for interaction with your medication.

- Be skeptical of "special diets" (such as the Cari Loder regimen) promoted as MS cures. There is no evidence that they work, and the best dietary approach is common sense healthy eating (low fat, high fiber, lots of fruits and vegetables).

Stress Management

It is important to find strategies to deal with the stress of living with a chronic and unpredictable condition. Many people with MS struggle with feelings of anger, depression, and a sense of loss of control. Some people find that stress can worsen MS symptoms such as fatigue.

Stress management techniques include deep breathing and other relaxation modalities, meditation, biofeedback, music therapy, yoga, tai chi, and massage therapy. Exercise is also an excellent way to reduce stress. Building a strong and positive support network of family and friends can also help you better deal with stress.

Preventing Respiratory Infections

MS symptoms worsen during a cold or the flu, probably because of increased immune system activity and fever. People with MS should receive a flu shot in the fall. However, they should not take the nasal spray version of the flu vaccine (FluMist Intranasal). Unlike the flu injection vaccine, which uses an inactivated virus, FluMist contains a live virus. Live virus vaccinations may be harmful for people with MS, especially those who take immune-suppressing drugs. Other live virus vaccines include shingles and polio, among others. People with MS should talk to their doctor about the safety of any of these vaccines.

Certain patients with MS are more likely to have severe forms of COVID-19, especially those who have more severe disabilities. The COVID vaccine is recommended for most people with MS.

Alternative Therapies

Reflexology involves placing pressure to specific areas of the feet or hands that are thought to correspond to parts of the body. Based on limited studies, the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) considers reflexology as possibly effective for reducing the "pins and needles" sensations (paresthesia) experienced by some people with MS. Paresthesia is characterized by tingling, prickling, or burning sensations in the hands, feet, legs, or arms.

Pulsed magnetic therapy may possibly help with MS fatigue symptoms, but not depression, according to the AAN guidelines.

Herbs and Supplements

Generally, manufacturers of herbal remedies and dietary supplements do not need FDA approval to sell their products. Just like a drug, herbs and supplements can affect the body's chemistry, and therefore have the potential to produce side effects that may be harmful. There have been a number of reported cases of serious and even lethal side effects from herbal products. Check with your provider before using any herbal remedies or dietary supplements.

The following are some popular herbal and supplement remedies for multiple sclerosis:

Marijuana (Cannabis).

Synthetic pill or oral spray forms of cannabis, commonly called marijuana, may help ease MS spasticity and pain, according to recent guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology. Dronabinol (Marinol) and nabilone (Cesamet) are pills that contain a synthetic form of the THC chemical found in marijuana. These pills are approved in the United States for treating cancer-associated nausea and vomiting, but are not approved for MS. Nabiximols (Sativex) is an oral spray currently approved in 25 countries, but not the United States, to treat MS spasms. (Nabiximols may also help with frequent urination.) The AAN finds inadequate evidence to recommend for or against smoking marijuana to treat MS symptoms. A 2015 trial found that this drug did not improve function in patients with MS.Gingko Biloba.

There is some evidence that the herbal remedy ginkgo biloba may help reduce fatigue, although not cognitive (thinking or memory) problems. Gingko biloba may cause an increased risk for bleeding when used at high doses. This herb can also interact with high doses of vitamin E, anti-clotting medications, aspirin, and NSAIDs.Vitamin D.

Vitamin D supplements are helpful for people with low levels of vitamin D in their blood. Vitamin D strengthens bone and may help prevent osteoporosis. A recommended daily dosage is 400 to 800 IU. For people with vitamin D deficiency, 1000 IU may be recommended. Vitamin D deficiency may be associated with worsening symptoms during the early course of MS. There currently is no evidence that Vitamin D affects the course of MS progression.Antioxidant Vitamins.

The MS disease process may be partly due to oxidation. However, no studies have proven the effectiveness of antioxidant vitamins (such as vitamins C and E) for MS. In addition, antioxidants may possibly activate T cells and macrophages (inflammatory components of the immune system) and might theoretically pose some danger to patients. Small studies to date have not found any worsening of the disease from taking vitamin supplements, but patients should be cautious.Bee Venom.

For years, anecdotal reports have claimed that bee stings relieve some MS symptoms. No studies have confirmed any benefits. Bee venom contains many chemicals, some of which can cause severe and sometimes deadly allergic reactions in some people.Linoleic Acid.

Linoleic acid, commonly known as evening primrose oil, is a polyunsaturated fatty acid believed by some people to be helpful because myelin is composed of fatty acids. No study has proven that it is beneficial, but it does not appear to cause any harm.

Resources

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke -- www.ninds.nih.gov

- American Academy of Neurology -- www.aan.com

- Multiple Sclerosis Association of America -- mymsaa.org

- National Multiple Sclerosis Society -- www.nationalmssociety.org

- Multiple Sclerosis Foundation -- msfocus.org

References

Benedict RHB, Amato MP, DeLuca J, Geurts JJG. Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis: clinical management, MRI, and therapeutic avenues. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(10):860-871. PMID: 32949546 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32949546/.

Brownlee WJ, Hardy TA, Fazekas F, Miller DH. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: progress and challenges. Lancet. 2017;389(10076):1336-1346. PMID: 27889190 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27889190/.

Chitnis T, Khoury SJ. Neuroimmunology. In: Jankovic J, Mazziotta JC, Pomeroy SL, Newman NJ, eds. Bradley and Daroff's Neurology in Clinical Practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 49.

Corboy JR, Weinshenker BG, Wingerchuk DM. Comment on 2018 American Academy of Neurology guidelines on disease-modifying therapies in MS. Neurology. 2018;90(24):1106-1112. PMID: 29685920 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29685920/.

Evans E, Piccio L, Cross AH. Use of vitamins and dietary supplements by patients with multiple sclerosis: a review. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(8):1013-1021. PMID: 29710293 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29710293/.

Fabian MT, Krieger SC, Lublin FD. Multiple sclerosis and other inflammatory demyelinating diseases of the central nervous system. In: Jankovic J, Mazziotta JC, Pomeroy SL, Newman NJ, eds. Bradley and Daroff's Neurology in Clinical Practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 80.

Faissner S, Plemel JR, Gold R, Yong VW. Progressive multiple sclerosis: from pathophysiology to therapeutic strategies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18(12):905-922. PMID: 31399729 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31399729/.

Furgiuele A, Cosentino M, Ferrari M, Marino F. Immunomodulatory potential of cannabidiol in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2021:1–19. PMID: 33492630 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33492630/.

Haselkorn JK, Hughes C, Rae-Grant A, et al. Summary of comprehensive systematic review: rehabilitation in multiple sclerosis: report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2015;85(21):1896-1903. PMID: 26598432 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26598432/.

Jagannath VA, Filippini G, Di Pietrantonj C, et al. Vitamin D for the management of multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;9:CD008422. PMID: 30246874 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30246874/.

Köpke S, Solari A, Rahn A, et al. Information provision for people with multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;10:CD008757. PMID: 30317542 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30317542/.

Koppel BS, Brust JC, Fife T, et al. Systematic review: efficacy and safety of medical marijuana in selected neurologic disorders: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2014;82(17):1556-1563. PMID: 24778283 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24778283/.

Lincoln MR, Schneider R, Oh J. Vitamin D as disease-modifying therapy for multiple sclerosis? Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2021 Apr 1:1-3. PMID: 33836645 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33836645/.

Minden SL, Feinstein A, Kalb RC, et al. Evidence-based guideline: assessment and management of psychiatric disorders in individuals with MS: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2014;82(2):174-181. PMID: 24376275 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24376275/.

Ontaneda D, Thompson AJ, Fox RJ, Cohen JA. Progressive multiple sclerosis: prospects for disease therapy, repair, and restoration of function. Lancet. 2017;389(10076):1357-1366. PMID: 27889191 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27889191/.

Pierrot-Deseilligny C, Souberbielle JC. Vitamin D and multiple sclerosis: an update. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2017;14:35-45. PMID: 28619429 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28619429/.

Rae-Grant A, Day GS, Marrie RA, et al. Practice guideline recommendations summary: disease-modifying therapies for adults with multiple sclerosis: report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2018;90(17):777-788. PMID: 29686116 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov//29686116/.

Reich DS, Lucchinetti CF, Calabresi PA. Multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(2):169-180. PMID: 29320652 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29320652/.

Sotirchos ES, Bhargava P, Eckstein C, et al. Safety and immunologic effects of high- vs low-dose cholecalciferol in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2016;86(4):382-390. PMID: 26718578 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26718578/.

Venasse M, Edwards T, Pilutti LA. Exploring wellness interventions in progressive multiple sclerosis: an evidence-based review. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2018;20(5):13. PMID: 29637453 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29637453/.

Yadav V, Bever C Jr, Bowen J, et al. Summary of evidence-based guideline: complementary and alternative medicine in multiple sclerosis: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2014;82(12):1083-1092. PMID: 24663230 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24663230/.

|

Review Date:

5/31/2021 Reviewed By: Joseph V. Campellone, MD, Department of Neurology, Cooper Medical School at Rowan University, Camden, NJ. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team. |